Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Metastasis detection in lymph nodes via microscopic examination of histopathological images is one of the most crucial diagnostic procedures for breast cancer staging. The manual analysis is extremely labor-intensive and time-consuming because of complexities and diversities of histopathology images. Deep learning has been utilized in automatic cancer metastasis detection in recent years. Due to the huge size of whole-slide images, most existing approaches split each image into smaller patches and simply treat these patches independently, which ignores the spatial correlations among them.

- deep learning

- convolutional neural network

- long short-term memory

- spatial constraint

1. Introduction

Cancer is currently one of the major causes of death for people all over the world. It is estimated that 14.5 million people have died of cancer, and by 2030, this figure is expected to exceed 28 million. The most common cancer in women is breast cancer. Every year, 2.1 million people around the world are diagnosed with breast cancer according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. Due to the high rate of mortality, considerable efforts have been made in recent decades to detect breast cancer from histological images so as to improve survival through early breast cancer detection or through breast tissue diagnosis.

Because lymph nodes are the first site of breast cancer metastasis, the metastasis identification of lymph nodes is one of the most essential criteria for early detection [2]. In order to analyze the characteristics of tissues, pathologists examine the tissue slices under a microscope [3]. The tissue slices are traditionally directly observed with the histopathologist’s naked eye, and visual data are assessed manually based on prior medical knowledge. The manual analysis is highly time consuming and labor intensive due to the diversities of histopathological images, especially for tiny lymph nodes. At the same time, depending on the histopathologist’s expertise, workload, and current mood, the manual diagnostic procedure is subjective and has limited repeatability. In addition, in the face of escalating diagnostic demands with increased cancer incidence, there is a serious shortage of pathologists [4]. Hundreds of biopsies must be diagnosed daily by pathologists, thus it is almost impossible to thoroughly examine entire slides. However, if only regions of interest are investigated, the chance of incorrect diagnosis may increase. To this end, in order to increase the efficiency and reliability of pathological examination, it is required to develop automatic detection techniques. Therefore, computer aided diagnosis (CAD) is established to improve the consistency, efficiency, and sensitivity of metastasis identification [5].

However, automated metastasis identification in sentinel lymph nodes from a whole-slide image (WSI) is extremely challenging for the following reasons. First, hard imitations in normal tissues usually look similar in morphology to metastatic areas, which leads to many false positives. Second, there is a great variety of biological structures and textures of metastatic and background areas. Third, the varied circumstances of histological image processing (for example, staining, cutting, sampling, and digitization) enhance the variations of the appearance of the image. This usually happens as tissue samples are taken at different time points or from different patients. Last but not least, WSIs are incredibly huge, approximately 100,000 pixels × 200,000 pixels, and may not be directly input into any existing methods for cancer identification. Another problem for automatic detection algorithms is how to analyze such a large pixel image effectively.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have developed rapidly in recent years and achieve outstanding breakthroughs, especially in computer vision, image processing and analysis. In histopathological diagnosis, AI has also exhibited potential advantages. With the help of AI-assisted diagnostic approaches, valuable information about diagnostics may be speedily extracted from big data, alleviating the workload of pathologists. At the same time, AI-aided diagnostics have more objective analysis capabilities and can avoid subjective discrepancies of manual analysis. To a certain extent, artificial intelligence helps not only to improve work efficiency but also to reduce the rate of misdiagnosis by pathologists.

In the past few decades, much work on breast histology image recognition has been done. Early research used hand-made features to capture tissue properties in specific areas for automatic detection [6][7][8]. However, hand-made features are not sufficiently discriminative to describe a wide variety of shapes and textures. With the emergence of powerful computers, deep learning technology has made remarkable progress in a variety of domains, including natural language understanding, speech recognition, computer vision, and image processing [9]. These methods have also been successfully employed in various modalities of medical images for classification, detection, and segmentation tasks [10][11][12]. Recently, deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been utilized to detect cancer metastases that can learn more effective feature representation and obtain higher detection accuracy in a data-driven approach [13][14][15]. As the size of WSI is extremely huge, most studies first extracted tiny patches (for example, 256 pixels × 256 pixels) from WSI, then deep CNN was trained to categorize these tiny patches to be tumorous or normal. The probability map was subsequently produced at the patch level and used for the metastasis identification of the original WSI. The spatial relationships were not explicitly modeled, as the patches were independently extracted and trained. Consequently, the predictions from adjacent regions may not be consistent in the inference stage.

The main contributions are:

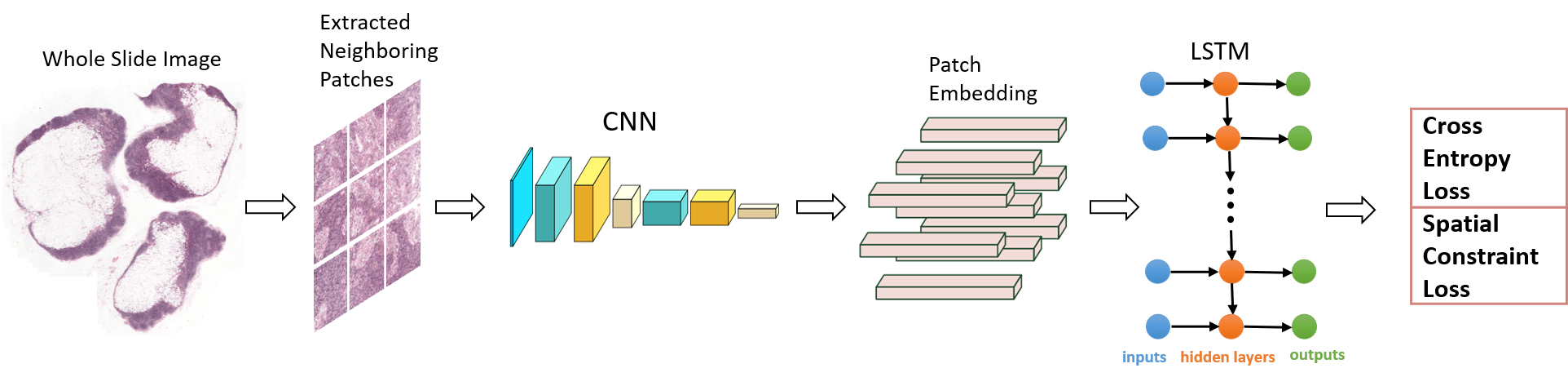

• Researchers propose a new spatially sensitive learning architecture that integrates CNN and long short-term memory (LSTM) in a unified framework to automatically

detect the metastasis locations, as shown in Figure 1.

detect the metastasis locations, as shown in Figure 1.

• Inspired by the observation that adjacent regions are interrelated, an LSTM layer is employed to explicitly describe the spatial correlation, at the same time, spatial

constraint is also imposed on the loss function to further improve performance.

constraint is also imposed on the loss function to further improve performance.

• Unlike previous approaches, the proposed model not only takes into account the appearance of each patch, but the spatial information between adjacent areas is also embedded into the framework to make better predictions.

Figure 1. Overview of the proposed framework. CNN and LSTM are two important components of this framework. When a grid of patches is input, the CNN feature extractor will encode every patch as a given-length vector representation. Given the grid of patch representations, the LSTM component models the spatial relationships between adjacent patches and outputs the probability of every patch being tumorous. In addition, spatial constraint is also imposed on the loss function to further improve the performance.

2. Breast Cancer Detection

In earlier years, most approaches employed hand-crafted features for cancer metastasis detection. In Reference [6], authors distinguished the malignant from the benign based on several hand-crafted textural features. Some studies merged two or more hand-crafted features to enhance the accuracy of detection. In Reference [7], graph, haralick, local binary patterns (LBP), and intensity features were used for cancer identification of H&E stained histopathological images. In Reference [8], histopathological images were represented via fusing color histograms, LBP, SIFT, and some kernel features, and the significance of these pattern features was also studied. However, it takes considerable effort to design and validate the hand-made features. In addition, the properties of tissues with great variations in morphology and texture cannot properly be represented. Therefore, the detection performance of these methods based on hand-crafted features is poor.

In Reference [16], authors developed a deep learning system to study the stromal properties of breast tissues associated with tumor for classifying whole slide images (WSIs). Authors in Reference [13] utilized AlexNet to categorize breast cancer in histopathological images to be malignant or benign. Authors in Reference [14] developed two distinct CNN architectures to classify breast cancer of pathology images. Single-task CNN was applied to identify malignant tumors. Multi-task CNN was used for analyzing the properties of benign and malignant tumors. The hybrid CNN unit designed in Reference [15] could fully exploit the global and local features of images, and thus obtained superior prediction performance. In References [17][18], authors proposed a dense and fast screening architecture (ScanNet) to identify metastatic breast cancer in WSIs. Several methods based on transfer learning are also proposed to detect breast cancer [19][20][21]. However, these above approaches deal with each patch of an image individually. In reality, each image patch and its adjacent ones generally share spatial correlations that are crucial for prediction. If one patch is a tumor, its adjacent patches are more likely in the tumor region, as they are situated in the neighboring areas.

In order to fully capture the spatial structure information between adjacent patches, authors in Reference [22] applied a conditional random field (CRF) on patch features, which are first obtained from a CNN classifier. However, the method [22] adopted a two-step learning framework, so the spatial relationships between neighboring patches are not available for the CNN feature extractor. Authors in Reference [23] employed 2D long short-term memory (LSTM) on patch features to learn spatial structure information, due to higher computation cost of the end-to-end learning scheme, the two-stage learning strategy was also adopted in their experiments [23].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/math10152657

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Apple, S.K. Sentinel lymph node in breast cancer: Review article from a pathologist’s point of view. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2016, 50, 83–95.

- Ramos-Vara, J.A. Principles and methods of immunohistochemistry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 691, 83–96.

- Humphreys, G.; Ghent, A. World laments loss of pathology service. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 564–565.

- Litjens, G.; Sánchez, C.; Timofeeva, N.; Hermsen, M.; Nagtegaal, I.; Kovacs, I.; Kaa, H.; Bult, P.; Ginnneken, B.V.; Laak, J. Deep learning as a tool for increased accuracy and efficiency of histopathological diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26286.

- Spanhol, F.A.; Oliveira, L.S.; Petitjean, C.; Heutte, L. A dataset for breast cancer histopathological image classification. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 63, 1455–1462.

- Cruz-Roa, A.A.; Ovalle, J.; Madabhushi, A.; Osorio, F. A Deep Learning Architecture for Image Representation, Visual Interpretability and Automated Basal-Cell Carcinoma Cancer Detection. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention, Nagoya, Japan, 22–26 September 2013; pp. 403–410.

- Kandemir, M.; Hamprecht, F. Computer-aided diagnosis from weak supervision: A benchmarking study. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2015, 42, 44–50.

- Alom, M.Z.; Taha, T.M.; Yakopcic, C.; Westberg, S.; Asari, V.K. The history began from alexnet: A comprehensive survey on deep learning approaches. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01164.

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; Laak, J.A.; Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88.

- Basha, J.; Bacanin, N.; Vukobrat, N.; Zivkovic, M.; Venkatachalam, K.; Hubálovský, S.; Trojovský, P. Chaotic Harris Hawks Optimization with Quasi-Reflection-Based Learning: An Application to Enhance CNN Design. Sensors 2021, 21, 6654.

- Manzo, M.; Pellino, S. Bucket of Deep Transfer Learning Features and Classification Models for Melanoma Detection. J. Imaging 2020, 6, 129.

- Spanhol, F.; Oliveira, L.S.; Cavalin, P.R.; Petitjean, C.; Heutte, L. Deep features for breast cancer histopathological image classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Banff, AB, Canada, 5–8 October 2017; pp. 1868–1873.

- Bayramoglu, N.; Kannala, J.; Heikkilä, J. Deep learning for magnification independent breast cancer histopathology image classification. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Cancun, Mexico, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 2440–2445.

- Guo, Y.; Dong, H.; Song, F.; Zhu, C.; Liu, J. Breast Cancer Histology Image Classification Based on Deep Neural Networks. In International Conference Image Analysis and Recognition; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10882, pp. 827–836.

- Ehteshami Bejnordi, B.; Linz, J.; Glass, B.; Mullooly, M.; Gierach, G.; Sherman, M.; Karssemeijer, N.; van der Laak, J.; Beck, A. Deep learning-based assessment of tumor-associated stroma for diagnosing breast cancer in histopathology images. In Proceedings of the IEEE 14th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 18–21 April 2017; pp. 929–932.

- Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Dou, Q.; Wang, L.; Qin, J.; Heng, P.A. ScanNet: A Fast and Dense Scanning Framework for Metastatic Breast Cancer Detection from Whole-Slide Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 539–546.

- Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Graham, S.; Dou, Q.; Rajpoot, N.; Heng, P.A. Fast scannet: Fast and dense analysis of multi-gigapixel whole-slide images for cancer metastasis detection. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 38, 1948–1958.

- Xie, J.; Liu, R.; Luttrell, J.; Zhang, C. Deep Learning Based Analysis of Histopathological Images of Breast Cancer. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 80.

- de Matos, J.; de Souza Britto, A.; Oliveira, L.; Koerich, A.L. Double Transfer Learning for Breast Cancer Histopathologic Image Classification. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Budapest, Hungary, 14–19 July 2019; pp. 1–8.

- Kassani, S.H.; Kassani, P.H.; Wesolowski, M.J.; Schneider, K.A.; Deters, R. Breast Cancer Diagnosis with Transfer Learning and Global Pooling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju, Korea, 16–18 October 2019; pp. 519–524.

- Zanjani, F.G.; Zinger, S.; With, P. Cancer detection in histopathology whole-slide images using conditional random fields on deep embedded spaces. In Proceedings of the Digital Pathology, Houston, TX, USA, 6 March 2018.

- Kong, B.; Xin, W.; Li, Z.; Qi, S.; Zhang, S. Cancer Metastasis Detection via Spatially Structured Deep Network. In International Conference Image Analysis and Recognition; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 236–248.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!