1. Introduction

Mitochondria in eukaryotic cells likely evolved from bacteria by endosymbiosis [

1,

2], and they are composed of two separate and functionally distinct membranes (the outer membrane and the inner membrane), the intermembrane space, and matrix compartments. Mitochondria also have a circular genome called mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) [

3]. The mitochondrial genome encompasses thousands of copies of the mtDNA and more than one thousand nuclear DNA (nDNA)-encoded genes [

4]. Mitochondria form a dynamic and interconnected network that is intimately integrated with other cellular compartments such as nuclear, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and plasma [

5,

6,

7]. Mitochondria are not only the center for energy metabolism, but also the headquarters for different catabolic and anabolic processes, calcium fluxes, and various signaling pathways [

8,

9,

10,

11]. During these processes, many intermediates are generated, which are critical for cell anabolic metabolism and cellular signaling, as well as for providing substrates required for epigenetic modification [

12]. Metabolites that are essential for epigenetic modification include acetyl coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA), oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD

+), α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), succinate, etc., and they perform diverse functions, including contributing to gene transcription modulation and cell fate determination.

The concept of epigenetics can be traced back to 1942. Waddington described the divergence between genotype and phenotype during development [

13]. Now, epigenetics commonly refers to heritable alterations in gene expression without DNA sequence changing [

14,

15]. Epigenetic modification mainly includes DNA and histone modifications, which lead to nucleosome remodeling and gene transcription alternations. There are many types of epigenetic modifications, but all are tightly regulated by the specific enzymes and the corresponding substrates required [

16]. The expression of enzymes is determined by the cell linage and state, while the substrates are highly dependent on the cell metabolism, which is tightly regulated by extracellular signaling and available nutrition [

17,

18,

19]. These epigenetic modifications are also strictly dependent on the cellular energy status [

20]. Metabolites generated in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) in mitochondria or related metabolism are crucial for epigenetics, which links the relation among mitochondria, gene expression, and cell fate dictation. We briefly explored the function of several important metabolites in basic epigenetics such as DNA methylation and histone modification. The aberration of epigenetics exerts a significant impact on cellular function, thus leading to the dysregulation of gene expression and finally resulting in various diseases, such as cancers [

21].

Oncogene overactivation and tumor suppressor inactivation transform somatic cells into cancer cells [

22,

23,

24]. This transformation can take place during tissue regeneration and can be accelerated under infections, toxins, or other metabolic influences that cause mutations [

25,

26]. After transformation, additional gene mutation, gene expression alteration, and change in tumor microenvironment drive tumor evolution [

27].

Historically, the notion of cancer stem cells (CSCs) is adopted from somatic stem cells, and it refers to a subpopulation of cancer cells with relatively slow cycling but that can regenerate the entire tumor after treatment. CSCs originate from either differentiated cells or tissue-resident stem cells [

28]. CSC was first discovered as the leukemia-initiating cell in human acute myeloid leukemia in 1994 [

29]. After that, CSCs were also found in tumors in the brain, breast, colon, liver, etc. [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. These CSCs drive tumor initiation and tumor malignant growth and are often responsible for drug resistance and relapses. Unlike normal somatic stem cells, CSCs evolve with tumor evolution, which results from additional gene expression alternations and tumor microenvironment changes. CSCs can propagate tumors and promote tumor progression compared with the non-tumorigenic cells within the bulk tumor [

35].

Metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming is essential for tumor initiation, evolution, and metastasis [

36,

37]. Epigenetics dictates the cell fate of both embryonic cells and somatic cells in differentiation and development [

38], and different epigenetic regulations on gene expression also affect tumorigenesis [

39,

40]. A multitude of epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation and post-translational modification of histones, contribute to diversity within tumors [

41,

42]. Epigenetic deregulation participates in the earliest stages of tumor initiation and has been increasingly recognized as a hallmark of cancer [

43,

44]. The deregulation of various epigenetic pathways contributes to tumorigenesis, especially concerning the maintenance and survival of CSCs [

35]. For example, DNA hypermethylation has been associated with the silencing of tumor suppressor genes as well as differentiation genes in various cancers [

45].

Considering the critical role of mitochondria in cellular metabolism and the essential role of epigenetics in tumorigenesis, it is recognized that the interplay between mitochondria metabolism and epigenetic enzymes plays a critical role in tumor initiation and evolution [

46,

47,

48,

49]. The metabolites such as acetyl-CoA, α-KG, S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), NAD

+, and O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) play crucial roles in cell fate determination by regulating epigenetic modifications and gene expression.

Tumorigenesis affected by both genetic and non-genetic determinants constitutes a major source of therapeutic resistance. Targeting epigenetics as well as mitochondrial metabolism has been demonstrated as a promising therapeutic strategy to inhibit tumor growth. Mitochondrial and epigenetic targeting cancer therapy reduces tumor malignancy and often exhibits synergistic effects when combined with classical cytotoxic cancer therapy.

2. Mitochondria Function in Epigenetic Regulation

Mitochondria are the energy and metabolic center in the cell, which are essential for catabolic and anabolic metabolism. Mitochondrial function is tightly regulated by the expression of the mitochondrial genome as well as the surrounding microenvironment, both of which determine the cellular level of acetyl-CoA, α-KG, SAM, NAD

+, and O-GlcNAc required for epigenetic modification [

50,

51]. Epigenetic modification is a genetic regulation model that is independent of DNA sequence and plays an important role in establishing and maintaining specific gene expression. DNA methylation, histone post-translational modification, and chromatin remodeling are the major forms of epigenetic modifications [

52,

53]. Epigenetic alterations are the main mechanisms in development and tumorigenesis. Mitochondria, as the main energy supplier, play a pivotal role in the regulation of epigenetics [

54].

2.1. Mitochondria and DNA Methylation

Methylation is the only known modification that occurs on DNA, RNA, and proteins [

55].

DNA methylation is a major form of DNA modification in the mammalian genome, which mainly occurs at cytosine in a dinucleotide CpG [

56,

57,

58]. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are responsible for the establishment and maintenance of methylation patterns [

59]. They transfer the methyl group donated from SAM to cytosine and generate 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [

60] (

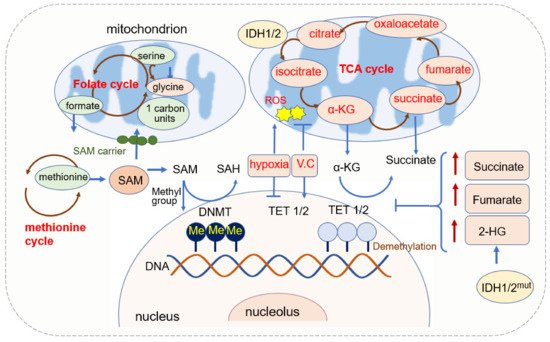

Figure 1). DNMT1 is responsible for maintaining the existing DNA methylation during DNA replication, and DNMT3A and DNMT3B are responsible for establishing de novo DNA methylation patterns [

61]. The pattern of DNA methylation in the genome changes is a dynamic process regulated by both de novo DNA methylation and demethylation [

62].

Figure 1. Mitochondrial function in DNA methylation.

The demethylation of DNA requires the function of the ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzyme. TETs belong to the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2-OGDO) family and their activity requires coenzyme factors such as Fe

2+ and α-KG [

63,

64]. They catalyze the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [

65,

66]. 5hmc resulted from the hydroxylation of methylcytosine and hydroxylation is involved in more than 90% reduction in cytosine methylation. 5hmC is not only an intermediate in the DNA demethylation process but also an independent epigenetic marker [

67,

68,

69,

70].

2.1.1. SAM Source and Mitochondrial Regulation of SAM

SAM is a significant biological sulfonium compound that participates in a variety of biochemical processes. SAM is synthesized through the reaction of methionine with ATP catalyzed by methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT). This reaction mainly occurs in the cytosol through the one-carbon (1C) metabolism pathway that encompasses both the folate and methionine cycles [

71]. Since SAM is synthesized in the cytosol [

72], it has to be transported into mitochondria by the mitochondrial SAM carrier, and it is converted into S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) in the methylation reaction of DNA, RNA, and proteins [

73]. SAH is further hydrolyzed in a reversible reaction by SAH hydrolase (SAHH) to give rise to adenosine and homocysteine. SAH is a competitive inhibitor of the methylation process, therefore both the increase of SAH and the decrease of SAM or SAM/SAH ratio inhibit the transmethylation reactions [

74,

75].

SAM is utilized in the cell by three metabolic pathways: transmethylation, transsulfuration, and polyamine synthesis [

72]. It is the universal and sole methyl donor to DNMTs. The methyl group from SAM can be transferred to a variety of substrates, including nucleic acids, proteins, phospholipids, biologic amines, and other small molecules [

74].

SAM levels are regulated by the level of methionine that is an essential amino acid in one-carbon metabolism, and methionine deficiency reduces liver SAM levels and H3K4 trimethylation drastically [

76]. 1C units can be generated from serine by cytosolic or mitochondrial folate metabolism, and the loss of mitochondrial pathway renders cells dependent on extracellular serine to make 1C units [

77].

2.1.2. α-KG Source and Its Function in DNA Methylation

α-KG is generated in cell cytoplasm via glycolysis and in mitochondria from isocitrate catalyzed by isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) [

78]. It is a membrane-impermeable crucial metabolite in the TCA cycle, contributing to the oxidation of nutrients such as amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids and it then provides energy for cell processes [

79]. The level of α-KG changes upon fasting, exercise, and aging [

80,

81].

α-KG possesses a variety of physiological functions, besides its function in the TCA cycle in ATP production, and it reacts with ammonia and is converted into glutamate and glutamine. It can be metabolized into succinate, carbon dioxide (CO

2), and water, and it also eliminates H

2O

2 by this process, acting as an antioxidant [

79,

82].

α-KG is an important metabolic intermediate and cofactor for several chromatin-modifying enzymes [

83]. The family of α-KG-dependent dioxygenases includes Jumonji C-domain (JmjC) lysine demethylases, TET DNA cytosine-oxidizing enzymes, and prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) [

84]. In terms of DNA methylation, α-KG is an essential cofactor for αKG-dependent dioxygenases and the TET family of DNA demethylases [

65,

66,

85]. α-KG is dramatically required and is increased for the activation of DNA methylation of the PRDM16 promoter during the early stage of adipogenesis [

86]. In AML, decreased intracellular α-KG levels cause DNA hypermethylation through altering TET activity [

87].

The level of α-KG is regulated by other metabolites. Fumarate and succinate, the intermediates of the TCA cycle and substrates of fumarate hydratase (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), are competitive inhibitors of α-KG-dependent dioxygenases [

88,

89,

90] (

Figure 1). The accumulation of fumarate and succinate caused by mutation of enzymes inhibits α-KG-dependent enzymes, including TETs [

91], thus leading to the global decreases in 5hmC and inactivation of FH and SDH and causing the loss of 5hmC [

90,

92,

93]. Both fumarate and succinate accumulation are involved in glycolytic pathways by the inhibition of TET1 and TET3 [

90]. FH-mediated TET inhibition promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT)-related transcription factors and enhances cell migration [

88]. Mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), another TCA enzyme, lead to the accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), and 2-HG acts as a competitive inhibitor of α-KG-dependent enzymes, including TETs [

66,

93]. IDH mutations not only generate 2-HG but also result in hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes [

94]. Non-specific α-KG analogue dimethyloxallyl glycine (DMOG) has been used as a TET inhibitor, which blocks multiple α-KG-dependent dioxygenases [

64].

2.1.3. Mitochondrial ROS and DNA Methylation

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is regarded as the byproduct of oxygen consumption and cellular metabolism [

95]. Mitochondria and NADPH oxidases (NOX) are two major contributors to endogenous ROS in tumor cells [

96]. ROS plays an important role in physiology and the pathophysiology of aerobic life [

97]. Excessive or inappropriately localized ROS damages cell growth. Higher levels of ROS contribute to tumor development through both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms [

98,

99,

100]. ROS also acts as signaling molecules in DNA damage, thus promoting genetic instability and tumorigenesis. ROS-induced oxidative stress is closely related to both hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoter regions and global hypomethylation.

ROS can function as the catalyst of DNA methylation by facilitating the transfer of methyl group to cytosine such as the formation of large complexes containing DNMT1/DNMT3B or increasing the expression of DNMTs, thus leading to hypermethylation of genes [

101,

102,

103]. DNMT expression can be upregulated by superoxide anion, which is a form of ROS. The elevation of superoxide anion upregulates DNMT1 and DNMT3B and inhibits superoxide anion, thus leading to a decrease in DNMT upregulation and DNA methylation. In colon cancer, H

2O

2 reduces the expression of RUNX1 by elevating methylation at its promoter [

104]. H

2O

2 also induces the upregulation of DNMT1 and HDAC1, thus leading to gene silence via histone deacetylation and promoter methylation [

105,

106]. In a brain function study, it was found that 5mC levels seemed to be increased and the 5hmC levels decreased coupled with increased ROS in the adult cerebellum, which suggested the promotion role of ROS in DNA methylation [

107].

Epigenetic modifications within the mammalian nuclear genome include DNA methylation (5mC) and hydroxymethylation (5hmC) or DNA demethylation [

65,

108]. DNA hydroxymethylation can occur as a result of oxidative stress or the action of TET1 [

65,

108]. Oxidative stress has been suggested to activate TET via the increased production of α-KG and leads to an increase in 5hmC levels [

109]. As the TET enzymes that convert 5mC to 5hmC may respond to oxidative stress, oxidative stress leads to the demethylation of genes. The redox-linked alterations to TET function can be reflected by the addition of ascorbate (vitamin C) to cellular 5hmC levels. Vitamin C is an antioxidant that can scavenge the primary ROS, and vitamin C treatment leads to an increase in 5hmC levels; thus, demethylation was promoted [

110,

111,

112].

Besides ROS, oxygen availability modulates both DNMT’s and TETs’ enzymatic activity, and hypoxia induces hypermethylation by reducing TET activity [

104,

113,

114]. DNA hypermethylation and hypoxia are well-recognized cancer hallmarks. TET belongs to the subfamily of 2OG oxygenases, which also act as an oxygen sensor [

115]. Tumor hypoxia directly reduces TET activity, thus causing a 5hmC decrease predominantly at gene promoters and enhancers. Reduced TET activity leads to an accumulation of 5mC, thus decreasing the expression of associated genes. 5hmC is reduced under hypoxia in a dose-dependent manner, with decreasing concentrations of purified TET1 and TET2 [

113].

2.1.4. Mitochondria Dysfunction and DNA Methylation

Mitochondrial dysfunction invokes mitochondria to nucleus responses [

116]. It reduces oxygen and SAM-CH

3 production in the cell, and the unbalanced redox homeostasis leads to perturbed methylation of nuclear DNA [

117]. The mtDNA copy number is one of the signals by which mitochondria affect nDNA methylation patterns; changes in mtDNA copy number, often observed in cancer, induce changes in nDNA methylation [

118]. Cells with depleted mitochondria (rho0 cell) result in the aberrant methylation of promoter CpG islands which were previously unmethylated in the parental cells, and the repletion of mitochondria back into rho0 cells reestablishes methylation partially to their original parental state, indicating the crucial role of mitochondria for DNA methylation [

118,

119].

The presence of mtDNA methylation is controversial [

120,

121,

122]. In 2011, Shock et al. reported that mammalian mitochondria have mtDNA cytosine methylation; mitochondrial DNA methyltransferase (mtDNMT1) binds to mtDNA in the mitochondrial matrix; mtDNMT1 is upregulated by nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1), PGC1-α, and the loss of p53. The expression of mtDNMT1 asymmetrically affects the expression of transcripts of mtDNA, and thus affects the function of mitochondria [

123,

124]. However, this discovery was overturned in 2021 by Lacopo Bicci et al. [

125], and they found that there is no CpG methylation in human mtDNA via whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) for studying the methylation of mtDNA.

The demethylase TETs’ activity requires coenzyme factors such as Fe2+ and α-KG. IDH mutation leads to the increase of succinate, fumarate, and 2-HG, and they inhibit TET activity. DNMTs transfer the methyl group from SAM to substrates. SAM is regulated by 1C unit metabolism. ROS can function as the catalysts of DNA methylation by facilitating the transfer of methyl group to cytosine and by adding vitamin C; an antioxidant can scavenge the ROS and leads to the increase in 5hmC. The oxidative stress also activates TET via increasing α-KG and finally leads to an increase in 5hmC.

2.2. Mitochondria and RNA Methylation

Over 100 different types of RNA modification have been identified. RNA methylation, especially the N6-methyladenine (m

6A) modification, is the most abundant RNA modification confirmed in viruses, yeast, and mammals [

126,

127]. m

6A modification was established by pioneering studies in 1974 [

128,

129]. Around 15,000 human genes have m

6A modification, which is a widespread regulatory mechanism that controls gene expression by affecting the splicing, stability, and translation efficiency of the modified mRNA molecules in diverse physiological processes [

127,

130,

131,

132]. m

6A RNA modification affects cell division, immune homeostasis, and biological rhythm. The dysregulation of m

6A modification has been suggested to drive human cancers [

133].

2.2.1. The Effect of Mitochondria-Associated Metabolites on RNA Methylation

RNA methyltransferases, also named RNA methylation writers such as METTL3-METTL14, move the methyl group from SAM to mRNA, and the demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 remove the RNA methylation [

134]. RNA methylation is decoded by proteins such as YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 [

130]. FTO and ALKBH5 belong to the α-KG-dependent dioxygenase family [

135]. The α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) is the first rate-limiting enzyme in the TCA cycle, and ALKBH5 promotes viral replication metabolically by upregulating OGDH [

136]. Furthermore, the enzymatic activity of FTO is inhibited in IDH mutation AML cells, thus leading to an increase in m

6A levels [

137,

138].

In addition, several mitochondrial proteins also regulate RNA methylation. For example, mitochondrial RNA methyltransferase METTL8 facilitates 3-methyl-cytidine (m

3C) methylation of the mt-tRNA and thus promotes mitochondrial ETC activity [

139].

2.2.2. The Roles of RNA Methylation in Mitochondria

Mitochondrial function is closely associated with RNA methylation, including both mRNA and tRNA methylation. Mitochondria possess specific translation machinery for the synthesis of proteins in ETC, and tRNA modification is indispensable during mitochondrial translation and the OXPHOS process, which require folate-dependent tRNA methylation [

140]. A recent study indicates that mitochondrial tRNA methylation is necessary for tumor metastasis due to its critical role in mitochondria gene translation [

141]. Moreover, tRNA methyltransferase 10C (TRMT10C), catalyzing the mitochondrial ND5 mRNA at N1-methyladenosine (m

1A) site, promotes cancer cell metabolism by reducing the mitochondrial ribonuclease P protein 1 (MRPP1) in mitochondria and inducing protein instability and mt-tRNA processing [

142]. In short, RNA methylation plays pivotal roles in mitochondrial synthesis and function.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11162518