Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Integrative & Complementary Medicine

The use of polyunsaturated fatty acids in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and developmental disorders has been gaining interest with preparations containing different dosages and combinations. Gamma-linolenic acid is an ω-6 fatty acid of emerging interest with potential roles as an adjuvant anti-inflammatory agent that could be used with ω-3 PUFAs in the treatment of ADHD and associated symptoms.

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- brain function

- brain structure

- cognition

- developmental

- difference

- gamma-linolenic acid (GLA)

- hyperactivity

- neuro-immune

- neuroinflammatory

- ω-3 PUFAs

- oxidative stress

- wellbeing

1. Introduction

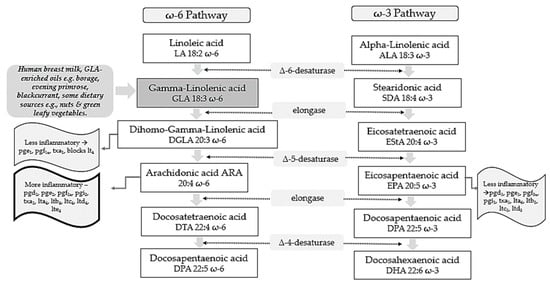

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) include two pathways of fatty acids—ω-3 and ω-6—which are both known to play major biological roles as structural and functional components of cell membranes and have a profound influence on the development of the central nervous system [1]. As shown in Figure 1, linoleic acid (LA) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) are precursors of ω-6 and ω-3 families, respectively and are regarded as essential fatty acids (EFAs) as they cannot be synthesized by the human body in amounts needed for health and wellbeing, and thus need to be supplied by diet [2,3]. These parent fatty acids yield arachidonic acid (ARA, ω-6), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, ω-3), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, ω-3) which regulate body homeostasis and act locally via bioactive signaling lipids called eicosanoids [3].

Figure 1. ω-6 and ω-3 family pathways. Key: pg, prostaglandin; pgi, prostacyclin; tx, thromboxane; lt, leukotriene.

Studies on evolutionary aspects of human diets indicate that major changes have taken place concerning types and profiles of dietary essential fatty acids obtained [4,5]. Genetically speaking, human beings in modern life live in a nutritional environment that differs from that which gave birth to their genetic pattern back in the evolutionary history of the genus Homo [5]. Whilst the dietary ratio of ω-6 to ω-3 fatty acids was once balanced and 1 to 1, in Western lifestyles this is now around 15–17 to 1 [4]. This is in stark contrast to recommendations from national agencies which advise that an ω-6 to ω-3 ratio of 4:1 is preferable [6]. It has been reported that lowering the ω-6 to ω-3 ratio to such thresholds could reduce enzymatic metabolic competition and facilitate the metabolism of more downstream products from ALA [7].

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V Edition (DSM-V), neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) are defined as a group of conditions with onset in the developmental period, inducing deficits that produce impairments of functioning [8,9]. NDDs comprise intellectual disability (ID), communication disorders, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), neurodevelopmental motor disorders, and specific learning disorders [8].

According to the DSM-V, ADHD diagnosis is based on some age-dependent symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity that interfere with functioning of development and should occur for at least 6 months [9]. ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder with onset in childhood, however, 50% of subjects continue to experience symptoms throughout adolescence and 30–60% in adulthood [10]. Overall pooled prevalence in the world is 7.2%; it is higher in males than in females, and it is most common in school-aged children [11]. Community prevalence of ADHD globally in children and young people has been reported to be between 2% and 7%, and an average of approximately 5% [12]. Other research reports a higher ADHD prevalence amongst boys, urban young people and those born to mothers with a history of psychiatric hospitalization [13].

2. GLA as an Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Molecule

GLA is composed of 18 carbon atoms with three double bonds and belongs to the category of ω-6 PUFAs [25]. GLA is present in human breast milk, a significant source for infants, and can be obtained from certain botanical seed oils and ingested from dietary supplements [25,26]. Natural sources of GLA include the oils of borage (Borago officinalis L., 20–26% GLA), black currant (Ribes nigrum L., 15–18%), and evening primrose (Oenothera biennis L., 8–12%) [25]. Some foods provide GLA in trace amounts, such as nuts and green leafy vegetables [26]. Unfortunately, GLA-rich foods are consumed in low quantities by the average person with the typical dietary intake of GLA being negligible [27].

Metabolically, as shown in Figure 1, GLA is produced in the body by the delta 6-desaturase enzyme acting on the parent fatty acid LA. It is then rapidly elongated to dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid (DGLA) by the enzyme elongase, acetylated, and incorporated into cell membrane phospholipids without resultant changes in ARA [28,29,30]. This has been demonstrated in in vivo metabolic research where GLA supplementation resulted in DGLA accumulation in neutrophil glycerolipids rather than ARA [31]. It has been postulated that this increase in DGLA relative to ARA within inflammatory cells such as neutrophils could diminish ARA metabolite biosynthesis [31]. This presents a plausible mechanism in terms of how dietary GLA could exert its anti-inflammatory effects [31].

Upon cell activation, DGLA is then released as free fatty acids (FAs) by phospholipase A2 and converted to several anti-inflammatory metabolites through competition with ARA for the enzymes cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) [32]. COX products from DGLA include prostaglandins 1 (PGE1), which can exert vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory actions [33,34]. 15-hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (15-HETrE) is also the 15-lipoxygenase product of DGLA which can inhibit proinflammatory eicosanoid biosynthesis and exert anti-inflammatory properties [30,35]. The Δ-6-desaturase activity appears to be altered by various factors. For example, desaturase mRNA levels may be influenced by the quantity and composition of dietary carbohydrates, protein, fats, and micronutrients including vitamin A, B12, folate, iron, zinc, and polyphenols [36]. Reduced enzyme activity is also observed in elderly people [27]. Other work suggests that Δ-6-desaturase activity could also be reduced in young children presenting signs of dry skin, desquamation, and thickening of the skin, as well as growth failure [27].

GLA and its metabolites have also been found to influence the expression of several genes, regulating levels of gene products including matrix proteins [26]. Such gene products are thought to have central roles in immune function and programmed cell death (apoptosis) [26]. Critical associations are also proposed between ADHD and the level of oxidative stress which can induce cell membrane damage, changes in inner structure and function of proteins, and DNA structural damage which eventually culminate in ADHD development [37].

3. GLA Synergy with EPA

ARA can also be synthesized from DGLA through Δ-5 desaturase, encoded by fatty acid desaturase 1 (FADS1) within the FADS gene cluster (Figure 1). ARA and its potent eicosanoid products (prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and lipoxins) play an important role in immune responses and inflammation [38]. Therefore, dietary supplementation with GLA has the capability to both increase levels of DGLA and its several anti-inflammatory metabolites, as well as ARA and its pro-inflammatory metabolic products and this might represent a therapeutic concern [25].

To counterbalance these pathways and make full use of the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of the molecule, the ω-3 long-chain-PUFAs (LC-PUFAs) EPA and DHA are often co-administered with GLA [39]. Humans supplemented with GLA, and EPA have substantially elevated blood EPA levels, but not ARA levels, suggesting that this supplement combination inhibits the development of pro-inflammatory ARA metabolites [39].

Evidence shows that 0.25 g/d EPA + DHA can block GLA-induced elevations in plasma ARA levels, while supplementation with borage + fish oil combinations inhibit leukotriene generation [40,41] and attenuate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines genes [42]. Furthermore, studies suggest that botanical oil combinations of borage oil, enriched in GLA, and echium oil (from Echium plantagineum L.) abundant in ω-3 PUFAs (ALA and stearidonic acids; SDA) enhanced the conversion of dietary GLA to DGLA whilst inhibiting the further conversion of DGLA to ARA [43]. Such supplementation strategies maintained the anti-inflammatory capacity of GLA, while increasing EPA, without causing accumulation of ARA.

This has been observed to directly translate into a clinical benefit in various therapeutic areas. For example, when enteral diets were enriched with marine oils containing EPA, DHA, and GLA, cytokine production and neutrophil recruitment in the lung were reduced, resulting in fewer days on ventilation and Intensive Care Unit stay-in patients with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [44]. Other research has observed decreased morbidity and mortality of critically ill patients with severe ARDS [45] and improved quality of life in asthma patients [40]. Positive outcomes of a combined ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs therapy have been observed in patients with rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis in a RCT, where treatment with ω-3 LC-PUFAs and GLA led to an increase of GLA and DGLA concentrations in plasma lipids, cholesteryl esters, and erythrocyte membranes, indicating a reduction in the production of ARA inflammatory eicosanoids [46].

4. GLA and ADHD Focus

Even though the pathogenetic pathways of NDDs are still not completely clear, growing scientific evidence points to oxidative stress and neuroinflammation as triggers for their genesis, and might be pivotal in their clinical pattern and evolution [47,48]. ω-6 and ω-3 PUFAs and their metabolites are involved in immune-inflammatory and brain structural mechanisms and therefore these molecules may play a role in neurological disorders in which disruption of these mechanisms represent a contributing pathogenetic factor [49,50].

4.1. Pathogenesis and Role of Neuroinflammation

The etiology of ADHD is multifactorial and still not fully understood. Evidence indicates that ADHD is heritable, however, no genes of major effect have been detected so far [51]. Pre- and peri-natal inflammatory factors that can affect the in-utero environment seem to be also involved in the etiology of the disease i.e., infections [52], smoking [53], obesity and poor diet [54], and pollutants to which the mother might be exposed [55,56]. Prenatal exposures to inflammation have also been associated with a volume reduction of cortical areas associated with ADHD [57]. Furthermore, a bilateral decrease in grey matter volume in the cingulate and parietal areas was observed in children with ADHD [57].

The hypothesis that inflammation is part of the pathway to ADHD and more in general to NDDs is consistent. Neuroinflammation influences brain development and subsequent risk of neurodevelopmental disorders through mechanisms such as glial activation [58], increased oxidative stress [59], aberrant neuronal development [60], reduced neurotrophic support [61], and altered neurotransmitter function [62]. Studies have identified associations between ADHD and regulatory genes involved in cell adhesion and inflammation, such as the gene for the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1 RA) [63]. Moreover, immune disorders such as eczema [64], asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, and hypothyroidism [65] are associated with greater rates of ADHD diagnosis.

Higher levels of antibodies against basal ganglia [66] and dopamine transporter [67] have been detected in subjects with ADHD. Furthermore, ADHD patients have reported increased cerebrospinal fluid levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor β (TNF- β) and lower amounts of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 [68]. This translates into an overall vulnerability of central nervous system (CNS) structures. Under normal conditions the blood–brain barrier (BBB) separates the peripheral immune system, preventing peripheral immune cells from entering the CNS. However, injuries, inflammatory diseases, and psychological stress may compromise the BBB, consequently, peripheral activated monocytes and T-lymphocytes may penetrate the brain, thereby inducing microglial activation, neuroinflammation, and neurotoxic responses [69].

A lack of dopamine in ADHD pathogenesis has been supported by the evidence that medications like methylphenidate and amphetamines, which increase the levels of dopamine in the synaptic cleft, can temporarily improve symptoms [70]. However, up to 30% of ADHD patients do not respond to this treatment, while only about 50% show signs of improvement [71]. Recent studies have provided evidence for the role of the monoamine serotonin (5-HT), synthesized from the essential amino acid tryptophan in a few areas of the brain such as the dorsal raphe nucleus, and which is an important regulator of behavioral inhibition [72]. Children with ADHD may have lower blood levels of 5-HT [73], which might contribute to the symptoms of ADHD [74]. Therefore, alternative pharmacological treatments for ADHD include selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and tri-cyclic-antidepressants (TCA) all of which target the 5-HT system [75].

Relevantly, some ω-3 PUFAs and some ω-6 PUFAs such as GLA are directly involved in the synthesis, release, and re-uptake of neurotransmitters [76], Subsequently, an ω-3 PUFAs deficiency or an imbalance between ω-6 and ω-3 PUFAs may lead to impaired neurological functioning and behavioral disturbances similar to those which characterize ADHD [76].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu14163273

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!