Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Although the population-level preference for the use of the right hand is the clearest example of behavioral lateralization, it represents only the best-known instance of a variety of functional asymmetries observable in humans. An interesting observation is that many of such asymmetries emerge during the processing of social stimuli, as often occurs in the case of human bodies, faces and voices.

- functional lateralization

- sensory asymmetries

- motor asymmetries

- right-handedness

- left-face bias

- left-cradling bias

- right ear advantage

1. Introduction

In humans, the population-level preference for the use of the right hand (around 90% of individuals being right-handed; e.g., see [1][2]) represents the clearest example of behavioral lateralization. However, it is only the best-known instance of a variety of functional asymmetries reported in humans, such as pseudoneglect [3], the right ear advantage (REA [4]), the left-face bias (LFB [5]), asymmetries in social touch [6], turning behavior [7] and similar. It is noteworthy that many of such asymmetries are observed during the processing of social stimuli, and in particular human bodies, faces and voices.

2. Auditory Asymmetries

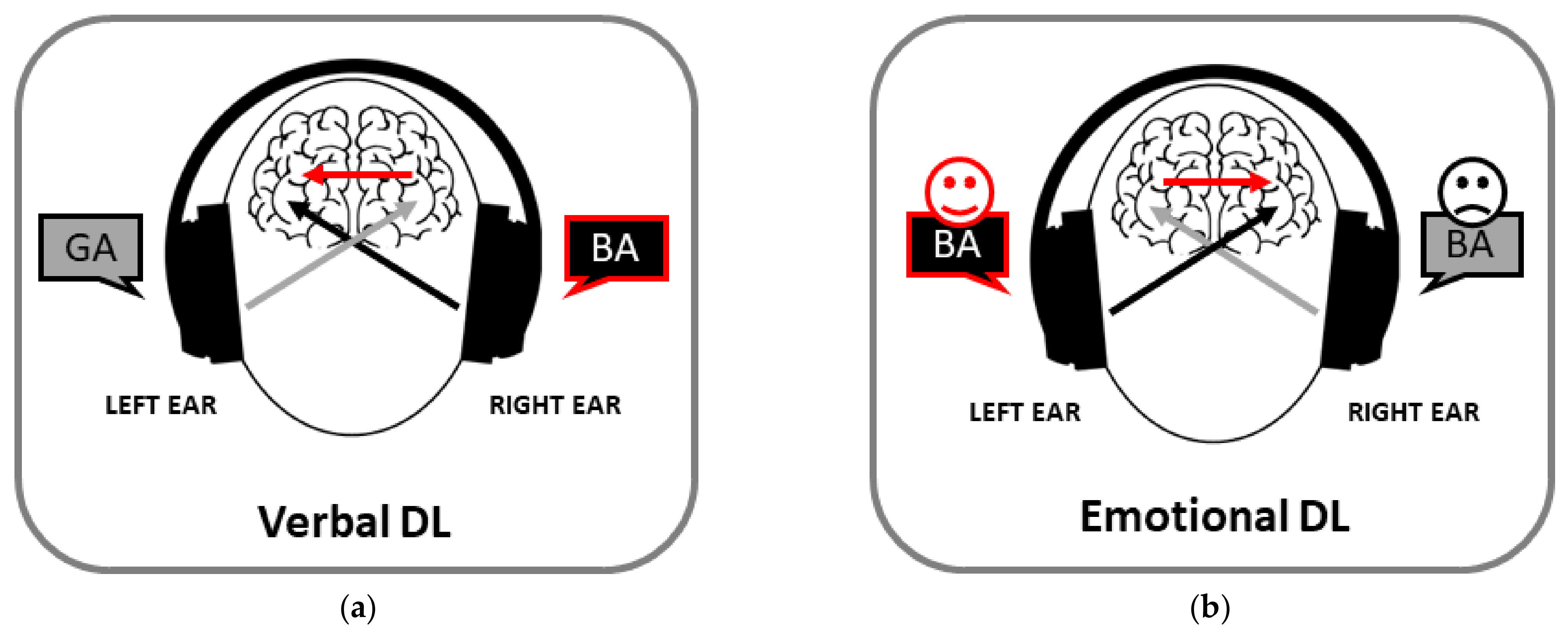

Historically, the dichotic listening paradigm turned out to be the first procedure to disclose asymmetries in the perception of social stimuli. It is 60 years since Doreen Kimura discovered the existence of a REA when different linguistic stimuli are presented simultaneously in the two ears [4][8]. This presentation mode—the so-called dichotic listening (DL)—was initially proposed by Broadbent [9] to study attention. However, it is only with Kimura’s discovery of a REA for speech sounds that such a paradigm was applied for the first time to neuropsychology. The original DL studies, consisting in the presentation of series of three, four or five pairs of digits to be reported later, had the limit of producing an effect of order and an involvement of working memory [10][11]. Consequently, the consonant–vowel (CV) syllable paradigm [12] was introduced, in which the stimuli typically consist of combinations of CV syllable pairs composed of the six stop consonants /b/, /d/, /g/, /k/, /p/, /t/ and the vowel /a/ (e.g., /ba/-/pa/) recorded as natural voices. In each trial, the two syllables of a pair are presented simultaneously, one in each ear, and participants have to identify and report the stimulus perceived first or best. Typically, they indicate more stimuli presented to the right than to the left ear (namely, the REA; Figure 1a). A REA is also observed in the discrimination of sound duration for CV syllables [13]. The mechanism at the basis of this effect can be accounted for by the structural, or neuroanatomical, model suggested by Kimura [14][15]. This model states that the REA is a consequence of the organization of cerebral auditory pathways, in which the contralateral pathway predominates over the ipsilateral one, in association with the specialization of the left temporal lobe for speech processing. It follows that the presentation of an auditory stimulus in one ear activates the contralateral auditory cortex more than the ipsilateral one [14][16][17], and that verbal stimuli presented to the right ear overcome those presented to the left ear. The input from the left ear can be transferred across the corpus callosum from the contralateral auditory cortex to reach the ipsilateral one [18], but such a transfer would cause a delay and attenuation of speech information. Besides the structural model, an attentional model has been proposed [19][20], according to which the perceptual asymmetry would be due to the dynamic imbalance in hemispheric activation, the left hemisphere being more activated than the right one by verbal inputs [21][22]. However, both models emphasize the left-hemispheric specialization for verbal stimuli.

Figure 1. Examples of verbal (a) and emotional (b) dichotic listening (DL). Participants tend to report the stimulus presented to the right and left ear, respectively.

The magnitude of the REA may vary among different populations, but it is observed from childhood [23][24] to old age [25], in males and females [24][26] and in right- and left-handers [27][28]. In addition, the REA for verbal material is observed across different languages in bilingual individuals [29][30][31], further confirming that this bias is related to the left-hemispheric specialization for language.

Further evidence of a right ear preference for linguistic sounds came from a dichotic speech illusion paradigm, in which a white noise could be presented alone or simultaneously with a vowel in one of the two ears: a right ear preference was found both when the verbal stimulus was absent and when it was present, extending the REA for verbal processing from the perceptual to the illusory domain [32]. The presence of a REA was also observed in paradigms involving imagery, and specifically in studies in which participants were invited to imagine hearing a voice in one ear only [33][34][35]. Interestingly, a REA seems to emerge also in ecological conditions, with listening individuals orienting their head so as to offer their right ear to a speaking individual during verbal exchanges in a noisy environment [36].

3. Visual Asymmetries

The second paradigm that revealed asymmetries in the perception of social stimuli is that of chimeric faces [37][38]. Levy et al. [38] photographed actors in smiling and neutral poses, cut down the photographs along their midsagittal axis and finally juxtaposed an emotional hemiface to a neutral hemiface of the same actor. Each chimeric face obtained in this way was presented together with its mirror image, one stimulus above the other, and the observers were required to select the face which looked happier in the pair. The scholars found that participants judged as more expressive the chimeras in which the emotional half was on the left side of the face from the observer’s point of view (and thus directly projected to the right hemisphere). The scholars also reported that this left visual field (LVF) advantage was stronger in right-handers than in left-handers, revealing that handedness plays a role in hemispheric asymmetries for faces, as confirmed by following studies (e.g., [39]). The main advantage of this paradigm is that of being a free-viewing presentation task, so that the printed stimuli can be observed for all the required time without affecting the LVF advantage. The chimeric face paradigm became a milestone in the field of hemispheric asymmetries for face processing [40] so that it was soon transformed into a computerized task, in which the presentation time of each stimulus is easily controllable, allowing for many experimental manipulations. For instance, the two chimeras can be presented either simultaneously, side by side [41], or one after the other, in the center of the screen [42]; response times can also be collected, further confirming the LVF advantage [43]. Facial features other than emotional expressions have been manipulated in the chimeric face paradigm, such as gender (female/male [44]), age (younger/older [5]) and ethnicity (e.g., Caucasian/Asian [45]). For instance, Chiang et al. [44] used a free viewing chimeric face paradigm and showed that the LVF advantage emerges by 6 years of age and reaches a plateau at about 10 years of age, as regards both emotions and gender. Burt and Perrett [5] extended the evidence of a LVF bias in adults to facial age and attractiveness.

Despite the great importance of the chimeric face paradigm in the research on hemispheric asymmetries for faces, other paradigms can be exploited to the same aim. Among these, the divided visual field (DVF) paradigm is based on the same neural assumptions as the chimeric face task, namely the contralateral projections of the human visual system [46]. In this paradigm, a stimulus is flashed in either the LVF or the right visual field (RVF) for less than 150 ms, which is about the minimum time needed to make a saccadic movement. In this way, a stimulus presented in the LVF or in the RVF is supposed to be directly projected to the right or left hemisphere, respectively (e.g., [47]). By means of such an experimental manipulation, the ability of one hemisphere in processing a specific stimulus can be directly compared with that of the opposite hemisphere, allowing researchers to further confirm the LVF advantage for faces [48]. The same paradigm has also been exploited to investigate another hemispheric imbalance, namely that for positive vs. negative emotional valence: for instance, in an electroencephalography study [49], angry (negative valence) and happy (positive valence) faces were presented either unilaterally (LVF or RVF) or bilaterally (one in the LVF and the other in the RVF, simultaneously). Behavioral results supported the so-called valence hypothesis [50], according to which the right and left hemispheres are specialized for negative and positive emotions, respectively, but the event-related potentials (ERPs) confirmed a right-hemispheric dominance for all emotional stimuli (see also [51][52]), as assumed by the right hemisphere hypothesis for emotional stimuli [53][54]. This unexpected evidence parallels the contrasting results found in previous research on hemispheric asymmetries in emotion processing, both theories receiving support from a number of studies (e.g., see [55]).

4. Perceptual and Attentional Asymmetries for Human Bodies

In more recent years, the DVF paradigm was also introduced in the study of human body parts, and in particular hands. Specifically, the lateralized presentation of bodies and body parts has been suggested as a way to study hemispheric asymmetries in motor representations [56][57][58]. For instance, it has been shown that participants respond faster when left and right hand stimuli are presented to the ipsilateral hemifield/contralateral hemisphere than when they are presented to the contralateral hemifield/ipsilateral hemisphere [56]. Moreover, Parsons et al. [58] found that callosotomy patients were faster and more accurate in judging the laterality of both left and right hand stimuli when they were presented to the ipsilateral hemifield/contralateral hemisphere than when they were presented to the contralateral hemifield/ipsilateral hemisphere (similar results were observed in healthy controls). In agreement with such findings, de Lussanet et al. [57] suggested that each hemisphere contains better visuo-motor representations for the contralateral body side than for the ipsilateral body side. Specifically, these scholars showed that—compared with leftward-facing point-light walkers (PLWs)—rightward-facing PLWs were recognized better in the RVF, whereas—compared with rightward-facing PLWs—leftward-facing PLWs were recognized better in the LVF. In other words, compared with PLWs facing toward the point of gaze, those facing away from the point of gaze appeared more vivid. Such a lateralized facing effect was explained by de Lussanet et al. [57] by proposing that the visual perception of lateralized body stimuli is facilitated when the corresponding visual and body representations are located in the same hemisphere (given the contralateral organization of both the visual and motor-somatosensory systems). Actually, this is true when a PLW faces away from the observer’s fixation point, so that a lateralized embodiment of the observed body is fostered because the hemibody seen in the foreground is processed by the sensory-motor cortex located in the same side as the visual cortex processing the stimulus.

It should be noticed that asymmetries in the perception of human bodies or body parts have also been reported in studies that do not resort to the DVF paradigm. Specifically, various studies investigating the perception of sport actions showed that the result of right limb actions is anticipated better than that of left limb actions [59][60][61][62][63][64][65]. As suggested by Hagemann [59] and Loffing et al. [61] (see also [60][62][63][65][66]), the ability to discriminate actions performed with the left hand is less developed than that to discriminate actions performed with the right hand. This is consistent with the advantage that left-handers and left-footers exhibit in several interactive sports [66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83].

5. Asymmetries in Social Touch

Many other examples of behavioral asymmetries can be found during social interactions among humans, and are mainly observed in complex motor activities such as embracing, kissing and infant-holding, wherein the motor behavior shared reciprocally by two persons entails necessarily a sensory counterpart, social touch [6][84]. Relatively few studies have systematically investigated the first two instances of interactive social touch, showing a substantial rightward asymmetry for both embracing [85][86] and kissing [87], with the latter finding being considered as more controversial (e.g., see [88]). As regards infant-holding, the left-cradling bias (LCB: the tendency to hold infants predominantly using the left rather than the right arm [89]; Figure 2) has received much more scholarly attention over the last 60 years. Although this lateralized behavior, refers to a motor rather than perceptual asymmetry, it nonetheless entails dealing with a human social stimulus (the infant) and seems to be related as well to perceptual asymmetries for social/emotional stimuli. Accordingly, there is a guiding thread exists between the aforementioned LVF advantage for faces, the higher social salience of infant facial features found in women than in men [90][91][92], and the left-sided infant positioning during cradling interactions being shown to a greater extent by women than by men [93]. First of all, it should be noticed that a fairly robust LCB has been shown—regardless of assessment methodologies—both in left-handed women (and men, although to a lesser degree [94][95]) and in a mother affected by situs inversus with dextrocardia (i.e., a condition in which the heart is atypically placed in the right rather than the left side of the chest [96]). Therefore, the two first explanations proposed, namely the “handedness” (i.e., cradling infants with the non-dominant hand would free the dominant arm for other tasks [97]) and “heartbeat” (i.e., cradling infants on the left side would enhance the soothing effect of the mother’s heartbeat sound [89]) hypotheses cannot be accepted as reliable accounts of the LCB. On the contrary, it is now believed that the LCB is due to a population-level right-hemispheric dominance for socio-emotional processing, as suggested by several studies carried out in this particular field over the last three decades (e.g., [98]). For example, Harris et al. [99] used the chimeric face paradigm in order to reveal the relationship between participants’ right-hemispheric specialization for processing facial emotion and their lateral cradling preference, as assessed by means of an imagination task. These scholars found that participants who imagined holding the infant on the left side showed a stronger LVF advantage (i.e., judged as more expressive the chimeras in which the emotional half was on the left side of the face) compared with participants who imagined holding the infant on the right side. Bourne and Todd [100] confirmed this finding using the chimeric face paradigm as well and a life-like doll to assess participants’ cradling lateral preferences. Consistent findings were reported by Vauclair and Donnot [101], who used a similar methodology (chimeric face paradigm and doll cradling task), although only in women.

Figure 2. Example of left-cradling bias (LCB).

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/sym14061096

References

- Coren, S. The Lateral Preference Inventory for Measurement of Handedness, Footedness, Eyedness, and Earedness: Norms for Young Adults. Bull. Psychon. Soc. 1993, 31, 1–3.

- Papadatou-Pastou, M.; Ntolka, E.; Schmitz, J.; Martin, M.; Munafò, M.R.; Ocklenburg, S.; Paracchini, S. Human Handedness: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 481–524.

- Jewell, G.; McCourt, M.E. Pseudoneglect: A Review and Meta-Analysis of Performance Factors in Line Bisection Tasks. Neuropsychologia 2000, 38, 93–110.

- Kimura, D. Cerebral Dominance and the Perception of Verbal Stimuli. Can. J. Psychol./Rev. Can. Psychol. 1961, 15, 166–171.

- Burt, D.M.; Perrett, D.I. Perceptual Asymmetries in Judgements of Facial Attractiveness, Age, Gender, Speech and Expression. Neuropsychologia 1997, 35, 685–693.

- Packheiser, J.; Schmitz, J.; Metzen, D.; Reinke, P.; Radtke, F.; Friedrich, P.; Güntürkün, O.; Peterburs, J.; Ocklenburg, S. Asymmetries in Social Touch-Motor and Emotional Biases on Lateral Preferences in Embracing, Cradling and Kissing. Laterality 2020, 25, 325–348.

- Stochl, J.; Croudace, T. Predictors of Human Rotation. Laterality 2013, 18, 265–281.

- Kimura, D. Some Effects of Temporal-Lobe Damage on Auditory Perception. Can. J. Psychol. 1961, 15, 156–165.

- Broadbent, D.E. The Role of Auditory Localization in Attention and Memory Span. J. Exp. Psychol. 1954, 47, 191–196.

- Bryden, M.P. An Overview of the Dichotic Listening Procedure and Its Relation to Cerebral Organization. In Handbook of Dichotic Listening: Theory, Methods and Research; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 1988; pp. 1–43. ISBN 978-0-471-91267-5.

- Bryden, M.P. Order of Report in Dichotic Listening. Can. J. Psychol./Rev. Can. Psychol. 1962, 16, 291–299.

- Shankweiler, D.; Studdert-Kennedy, M. Identification of Consonants and Vowels Presented to Left and Right Ears. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1967, 19, 59–63.

- Brancucci, A.; D’Anselmo, A.; Martello, F.; Tommasi, L. Left Hemisphere Specialization for Duration Discrimination of Musical and Speech Sounds. Neuropsychologia 2008, 46, 2013–2019.

- Kimura, D. Functional Asymmetry of the Brain in Dichotic Listening. Cortex 1967, 3, 163–178.

- Sidtis, J.J. Dichotic Listening after Commissurotomy. In Handbook of Dichotic Listening: Theory, Methods and Research; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 1988; pp. 161–184. ISBN 978-0-471-91267-5.

- Brancucci, A.; Babiloni, C.; Babiloni, F.; Galderisi, S.; Mucci, A.; Tecchio, F.; Zappasodi, F.; Pizzella, V.; Romani, G.L.; Rossini, P.M. Inhibition of Auditory Cortical Responses to Ipsilateral Stimuli during Dichotic Listening: Evidence from Magnetoencephalography. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 19, 2329–2336.

- Della Penna, S.; Brancucci, A.; Babiloni, C.; Franciotti, R.; Pizzella, V.; Rossi, D.; Torquati, K.; Rossini, P.M.; Romani, G.L. Lateralization of Dichotic Speech Stimuli Is Based on Specific Auditory Pathway Interactions: Neuromagnetic Evidence. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 17, 2303–2311.

- Pollmann, S.; Maertens, M.; von Cramon, D.Y.; Lepsien, J.; Hugdahl, K. Dichotic Listening in Patients with Splenial and Nonsplenial Callosal Lesions. Neuropsychology 2002, 16, 56–64.

- Kinsbourne, M. Dichotic Imbalance Due to Isolated Hemisphere Occlusion or Directional Rivalry? Brain Lang. 1980, 11, 221–224.

- Kinsbourne, M. The Cerebral Basis of Lateral Asymmetries in Attention. Acta Psychol. 1970, 33, 193–201.

- Binder, J.R.; Frost, J.A.; Hammeke, T.A.; Bellgowan, P.S.; Springer, J.A.; Kaufman, J.N.; Possing, E.T. Human Temporal Lobe Activation by Speech and Nonspeech Sounds. Cereb. Cortex 2000, 10, 512–528.

- Brancucci, A.; Tommasi, L. “Binaural Rivalry”: Dichotic Listening as a Tool for the Investigation of the Neural Correlate of Consciousness. Brain Cogn. 2011, 76, 218–224.

- Fennell, E.B.; Satz, P.; Morris, R. The Development of Handedness and Dichotic Ear Listening Asymmetries in Relation to School Achievement: A Longitudinal Study. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1983, 35, 248–262.

- Hirnstein, M.; Westerhausen, R.; Korsnes, M.S.; Hugdahl, K. Sex Differences in Language Asymmetry Are Age-Dependent and Small: A Large-Scale, Consonant-Vowel Dichotic Listening Study with Behavioral and FMRI Data. Cortex 2013, 49, 1910–1921.

- Westerhausen, R.; Bless, J.; Kompus, K. Behavioral Laterality and Aging: The Free-Recall Dichotic-Listening Right-Ear Advantage Increases With Age. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2015, 40, 313–327.

- Voyer, D. Sex Differences in Dichotic Listening. Brain Cogn. 2011, 76, 245–255.

- Bryden, M.P. Correlates of the Dichotic Right-Ear Effect. Cortex 1988, 24, 313–319.

- Dos Santos Sequeira, S.; Woerner, W.; Walter, C.; Kreuder, F.; Lueken, U.; Westerhausen, R.; Wittling, R.A.; Schweiger, E.; Wittling, W. Handedness, Dichotic-Listening Ear Advantage, and Gender Effects on Planum Temporale Asymmetry--a Volumetric Investigation Using Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neuropsychologia 2006, 44, 622–636.

- Bedoin, N.; Ferragne, E.; Marsico, E. Hemispheric Asymmetries Depend on the Phonetic Feature: A Dichotic Study of Place of Articulation and Voicing in French Stops. Brain Lang. 2010, 115, 133–140.

- D’Anselmo, A.; Reiterer, S.; Zuccarini, F.; Tommasi, L.; Brancucci, A. Hemispheric Asymmetries in Bilinguals: Tongue Similarity Affects Lateralization of Second Language. Neuropsychologia 2013, 51, 1187–1194.

- Tanaka, S.; Kanzaki, R.; Yoshibayashi, M.; Kamiya, T.; Sugishita, M. Dichotic Listening in Patients with Situs Inversus: Brain Asymmetry and Situs Asymmetry. Neuropsychologia 1999, 37, 869–874.

- Prete, G.; D’Anselmo, A.; Brancucci, A.; Tommasi, L. Evidence of a Right Ear Advantage in the Absence of Auditory Targets. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15569.

- Altamura, M.; Prete, G.; Elia, A.; Angelini, E.; Padalino, F.A.; Bellomo, A.; Tommasi, L.; Fairfield, B. Do Patients with Hallucinations Imagine Speech Right? Neuropsychologia 2020, 146, 107567.

- Prete, G.; Marzoli, D.; Brancucci, A.; Tommasi, L. Hearing It Right: Evidence of Hemispheric Lateralization in Auditory Imagery. Hear. Res. 2016, 332, 80–86.

- Prete, G.; Tommasi, V.; Tommasi, L. Right News, Good News! The Valence Hypothesis and Hemispheric Asymmetries in Auditory Imagery. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 2020, 35, 409–419.

- Marzoli, D.; Tommasi, L. Side Biases in Humans (Homo Sapiens): Three Ecological Studies on Hemispheric Asymmetries. Naturwissenschaften 2009, 96, 1099–1106.

- Schwartz, M.; Smith, M.L. Visual Asymmetries with Chimeric Faces. Neuropsychologia 1980, 18, 103–106.

- Levy, J.; Heller, W.; Banich, M.T.; Burton, L.A. Asymmetry of Perception in Free Viewing of Chimeric Faces. Brain Cogn. 1983, 2, 404–419.

- Bourne, V.J. Examining the Relationship between Degree of Handedness and Degree of Cerebral Lateralization for Processing Facial Emotion. Neuropsychology 2008, 22, 350–356.

- Voyer, D.; Voyer, S.D.; Tramonte, L. Free-Viewing Laterality Tasks: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychology 2012, 26, 551–567.

- Nicholls, M.E.R.; Smith, A.; Mattingley, J.B.; Bradshaw, J.L. The Effect of Body and Environment-Centred Coordinates on Free-Viewing Perceptual Asymmetries for Vertical and Horizontal Stimuli. Cortex 2006, 42, 336–346.

- Tommasi, V.; Prete, G.; Tommasi, L. Assessing the Presence of Face Biases by Means of Anorthoscopic Perception. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2020, 82, 2673–2692.

- Bourne, V.J. Chimeric Faces, Visual Field Bias, and Reaction Time Bias: Have We Been Missing a Trick? Laterality 2008, 13, 92–103.

- Chiang, C.H.; Ballantyne, A.O.; Trauner, D.A. Development of Perceptual Asymmetry for Free Viewing of Chimeric Stimuli. Brain Cogn. 2000, 44, 415–424.

- Prete, G.; Tommasi, L. The Own-Race Bias and the Cerebral Hemispheres. Soc. Neurosci. 2019, 14, 549–558.

- Bourne, V.J. The Divided Visual Field Paradigm: Methodological Considerations. Laterality 2006, 11, 373–393.

- Prete, G.; Laeng, B.; Tommasi, L. Lateralized Hybrid Faces: Evidence of a Valence-Specific Bias in the Processing of Implicit Emotions. Laterality 2014, 19, 439–454.

- Prete, G.; Marzoli, D.; Tommasi, L. Upright or Inverted, Entire or Exploded: Right-Hemispheric Superiority in Face Recognition Withstands Multiple Spatial Manipulations. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1456.

- Prete, G.; Capotosto, P.; Zappasodi, F.; Tommasi, L. Contrasting Hemispheric Asymmetries for Emotional Processing from Event-Related Potentials and Behavioral Responses. Neuropsychology 2018, 32, 317–328.

- Davidson, R.J.; Mednick, D.; Moss, E.; Saron, C.; Schaffer, C.E. Ratings of Emotion in Faces Are Influenced by the Visual Field to Which Stimuli Are Presented. Brain Cogn. 1987, 6, 403–411.

- Wyczesany, M.; Capotosto, P.; Zappasodi, F.; Prete, G. Hemispheric Asymmetries and Emotions: Evidence from Effective Connectivity. Neuropsychologia 2018, 121, 98–105.

- Prete, G.; Croce, P.; Zappasodi, F.; Tommasi, L.; Capotosto, P. Exploring Brain Activity for Positive and Negative Emotions by Means of EEG Microstates. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3404.

- Gainotti, G. Emotional Behavior and Hemispheric Side of the Lesion. Cortex 1972, 8, 41–55.

- Gainotti, G. Unconscious Processing of Emotions and the Right Hemisphere. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 205–218.

- Stanković, M. A Conceptual Critique of Brain Lateralization Models in Emotional Face Perception: Toward a Hemispheric Functional-Equivalence (HFE) Model. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2021, 160, 57–70.

- Aziz-Zadeh, L.; Iacoboni, M.; Zaidel, E. Hemispheric Sensitivity to Body Stimuli in Simple Reaction Time. Exp. Brain Res. 2006, 170, 116–121.

- De Lussanet, M.H.E.; Fadiga, L.; Michels, L.; Seitz, R.J.; Kleiser, R.; Lappe, M. Interaction of Visual Hemifield and Body View in Biological Motion Perception. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 27, 514–522.

- Parsons, L.M.; Gabrieli, J.D.; Phelps, E.A.; Gazzaniga, M.S. Cerebrally Lateralized Mental Representations of Hand Shape and Movement. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 6539–6548.

- Hagemann, N. The Advantage of Being Left-Handed in Interactive Sports. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2009, 71, 1641–1648.

- Loffing, F.; Hagemann, N.; Schorer, J.; Baker, J. Skilled Players’ and Novices’ Difficulty Anticipating Left- vs. Right-Handed Opponents’ Action Intentions Varies across Different Points in Time. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2015, 40, 410–421.

- Loffing, F.; Schorer, J.; Hagemann, N.; Baker, J. On the Advantage of Being Left-Handed in Volleyball: Further Evidence of the Specificity of Skilled Visual Perception. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2012, 74, 446–453.

- Loffing, F.; Hagemann, N. Zum Einfluss Des Anlaufwinkels Und Der Füßigkeit Des Schützen Auf Die Antizipation von Elfmeterschüssen. Z. Sportpsychol. 2015, 21, 63–73.

- Loffing, F.; Hagemann, N. Motor Competence Is Not Enough: Handedness Does Not Facilitate Visual Anticipation of Same-Handed Action Outcome. Cortex 2020, 130, 94–99.

- McMorris, T.; Colenso, S. Anticipation of Professional Soccer Goalkeepers When Facing Right-and Left-Footed Penalty Kicks. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1996, 82, 931–934.

- Schorer, J.; Loffing, F.; Hagemann, N.; Baker, J. Human Handedness in Interactive Situations: Negative Perceptual Frequency Effects Can Be Reversed! J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 507–513.

- Richardson, T.; Gilman, R.T. Left-Handedness Is Associated with Greater Fighting Success in Humans. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15402.

- Bisiacchi, P.; Ripoll, H.; Stein, J.; Simonet, P.; Azemar, G. Left-Handedness in Fencers: An Attentional Advantage? Percept. Mot. Ski. 1985, 61, 507–513.

- Breznik, K. On the Gender Effects of Handedness in Professional Tennis. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2013, 12, 346–353.

- Brooks, R.; Bussière, L.F.; Jennions, M.D.; Hunt, J. Sinister Strategies Succeed at the Cricket World Cup. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2004, 271 (Suppl. S3), S64–S66.

- Cingoz, Y.E.; Gursoy, R.; Ozan, M.; Hazar, K.; Dalli, M. Research on the Relation between Hand Preference and Success in Karate and Taekwondo Sports with Regards to Gender. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2018, 8, 308.

- Dochtermann, N.A.; Gienger, C.M.; Zappettini, S. Born to Win? Maybe, but Perhaps Only against Inferior Competition. Anim. Behav. 2014, 96, e1–e3.

- Goldstein, S.R.; Young, C.A. “ Evolutionary” Stable Strategy of Handedness in Major League Baseball. J. Comp. Psychol. 1996, 110, 164.

- Grouios, G. Motoric Dominance and Sporting Excellence: Training versus Heredity. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2004, 98, 53–66.

- Grouios, G.; Koidou, E.; Tsormpatzoudis, C.; Alexandris, K. Handedness in Sport. J. Hum. Mov. Stud. 2002, 43, 347–361.

- Gursoy, R. Effects of Left- or Right-Hand Preference on the Success of Boxers in Turkey. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 142–144.

- Harris, L.J. In Fencing, What Gives Left-Handers the Edge? Views from the Present and the Distant Past. Laterality 2010, 15, 15–55.

- Holtzen, D.W. Handedness and Professional Tennis. Int. J. Neurosci. 2000, 105, 101–119.

- Lawler, T.P.; Lawler, F.H. Left-Handedness in Professional Basketball: Prevalence, Performance, and Survival. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2011, 113, 815–824.

- Loffing, F.; Hagemann, N.; Strauss, B. Left-Handedness in Professional and Amateur Tennis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49325.

- Loffing, F.; Hagemann, N. Pushing through Evolution? Incidence and Fight Records of Left-Oriented Fighters in Professional Boxing History. Laterality Asymmetries Body Brain Cogn. 2015, 20, 270–286.

- Pollet, T.V.; Stulp, G.; Groothuis, T.G. Born to Win? Testing the Fighting Hypothesis in Realistic Fights: Left-Handedness in the Ultimate Fighting Championship. Anim. Behav. 2013, 86, 839–843.

- Tran, U.S.; Voracek, M. Footedness Is Associated with Self-Reported Sporting Performance and Motor Abilities in the General Population. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1199.

- Ziyagil, M.A.; Gursoy, R.; Dane, S.; Yuksel, R. Left-Handed Wrestlers Are More Successful. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2010, 111, 65–70.

- Ocklenburg, S.; Packheiser, J.; Schmitz, J.; Rook, N.; Güntürkün, O.; Peterburs, J.; Grimshaw, G.M. Hugs and Kisses—The Role of Motor Preferences and Emotional Lateralization for Hemispheric Asymmetries in Human Social Touch. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 95, 353–360.

- Packheiser, J.; Rook, N.; Dursun, Z.; Mesenhöller, J.; Wenglorz, A.; Güntürkün, O.; Ocklenburg, S. Embracing Your Emotions: Affective State Impacts Lateralisation of Human Embraces. Psychol. Res. 2019, 83, 26–36.

- Turnbull, O.H.; Stein, L.; Lucas, M.D. Lateral Preferences in Adult Embracing: A Test of the “Hemispheric Asymmetry” Theory of Infant Cradling. J. Genet. Psychol. 1995, 156, 17–21.

- Güntürkün, O. Adult Persistence of Head-Turning Asymmetry. Nature 2003, 421, 711.

- Sedgewick, J.R.; Holtslander, A.; Elias, L.J. Kissing Right? Absence of Rightward Directional Turning Bias During First Kiss Encounters Among Strangers. J. Nonverbal. Behav. 2019, 43, 271–282.

- Salk, L. The Effects of the Normal Heartbeat Sound on the Behaviour of the Newborn Infant: Implications for Mental Health. World Ment. Health 1960, 12, 168–175.

- Glocker, M.L.; Langleben, D.D.; Ruparel, K.; Loughead, J.W.; Valdez, J.N.; Griffin, M.D.; Sachser, N.; Gur, R.C. Baby Schema Modulates the Brain Reward System in Nulliparous Women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9115–9119.

- Hahn, A.C.; Perrett, D.I. Neural and Behavioral Responses to Attractiveness in Adult and Infant Faces. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 46, 591–603.

- Proverbio, A.M. Sex Differences in Social Cognition: The Case of Face Processing. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 222–234.

- Malatesta, G.; Marzoli, D.; Prete, G.; Tommasi, L. Human Lateralization, Maternal Effects and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 668520.

- Packheiser, J.; Schmitz, J.; Berretz, G.; Papadatou-Pastou, M.; Ocklenburg, S. Handedness and Sex Effects on Lateral Biases in Human Cradling: Three Meta-Analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 104, 30–42.

- Donnot, J.; Vauclair, J. Biais de latéralité dans la façon de porter un très jeune enfant: Une revue de la question. Neuropsychiatr. Enfance Adolesc. 2005, 53, 413–425.

- Todd, B.; Butterworth, G. Her Heart Is in the Right Place: An Investigation of the ‘Heartbeat Hypothesis’ as an Explanation of the Left Side Cradling Preference in a Mother with Dextrocardia. Early Dev. Parent. 1998, 7, 229–233.

- Van der Meer, A.; Husby, Å. Handedness as a Major Determinant of Functional Cradling Bias. Laterality 2006, 11, 263–276.

- Manning, J.T.; Chamberlain, A.T. Left-Side Cradling and Brain Lateralization. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1991, 12, 237–244.

- Harris, L.J.; Almerigi, J.B.; Carbary, T.J.; Fogel, T.G. Left-Side Infant Holding: A Test of the Hemispheric Arousal-Attentional Hypothesis. Brain Cogn. 2001, 46, 159–165.

- Bourne, V.J.; Todd, B.K. When Left Means Right: An Explanation of the Left Cradling Bias in Terms of Right Hemisphere Specializations. Dev. Sci. 2004, 7, 19–24.

- Vauclair, J.; Donnot, J. Infant Holding Biases and Their Relations to Hemispheric Specializations for Perceiving Facial Emotions. Neuropsychologia 2005, 43, 564–571.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!