- microparticles

- nanoparticles

- neurodegenerative disorders

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Parkinson’s disease

- nose-to-brain

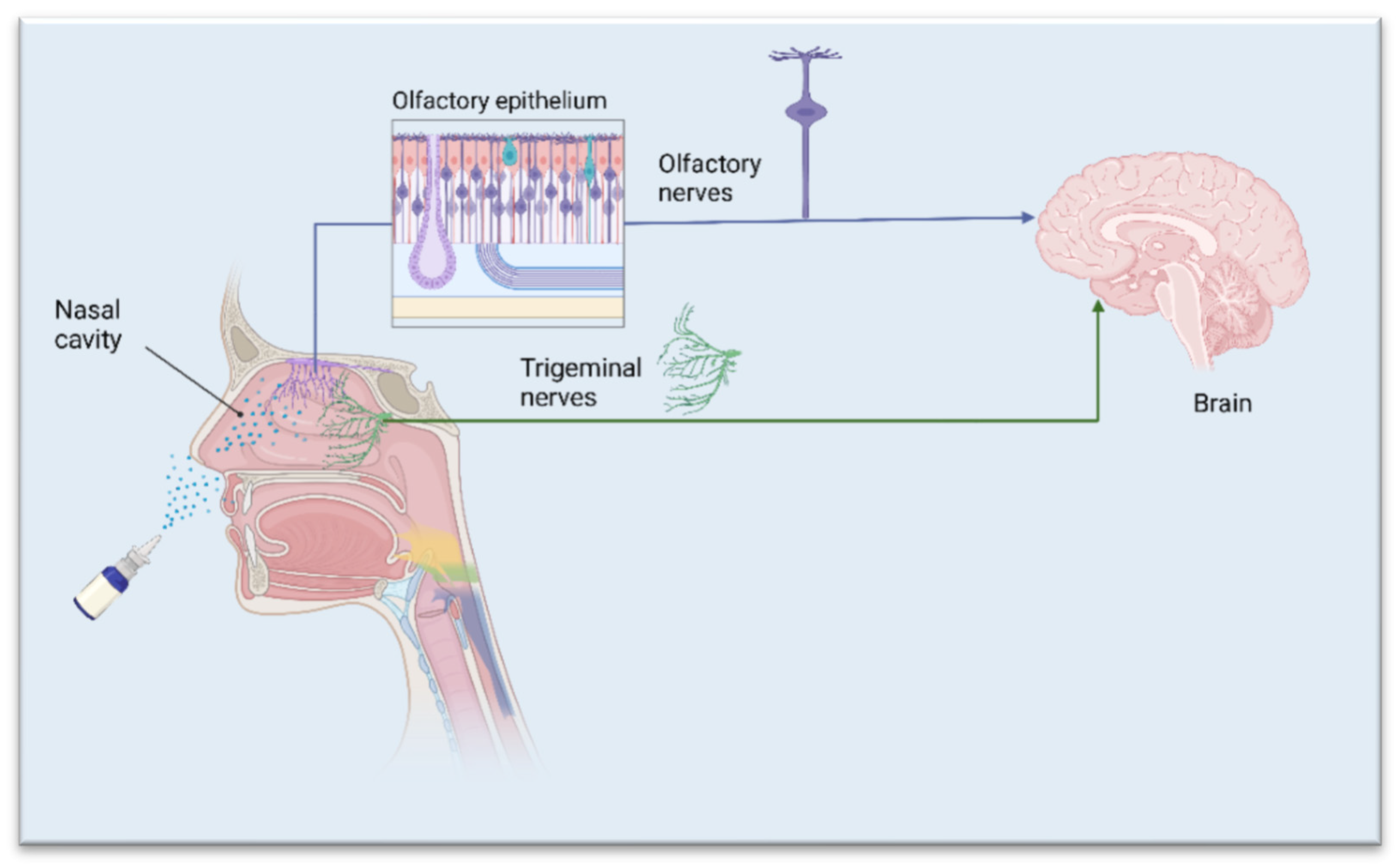

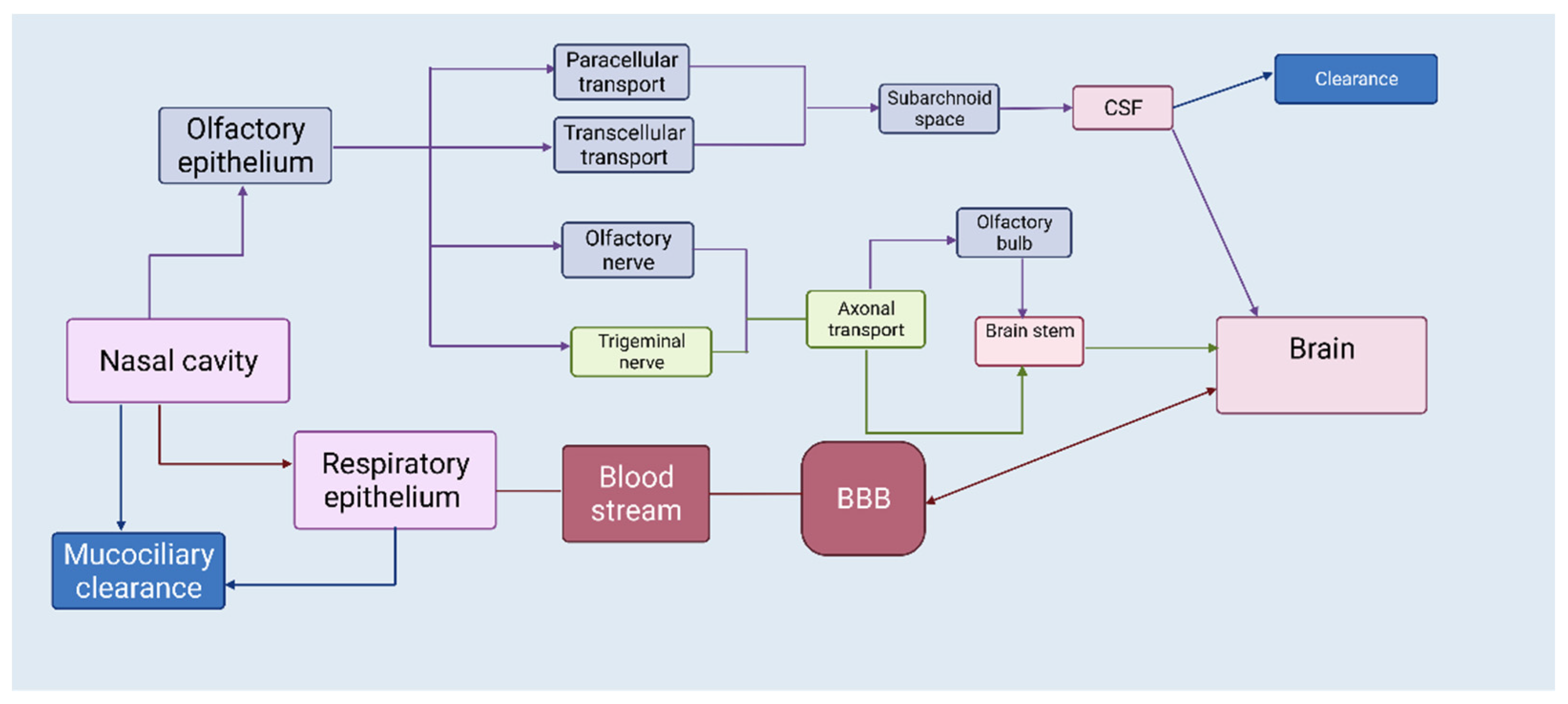

1. The Nasal Route—A Shortcut to Deliver Therapeutics Directly to the Brain

2. APIs Suited for Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery

3. Micro- and Nanoparticles for Nose-to-Brain Delivery

4. Microparticles

| Active Ingredient | Polymer/Lipid | Preparation Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric microparticles | |||

| β-cyclodextrin, Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin |

Chitosan, Alginate | Spray-drying | [31] |

| Deferoxamine mesylate | Chitosan, Methyl-β-cyclodextrin |

Spray-drying, Freeze-drying |

[32] |

| Ropinirole | Alginate, Chitosan | Spray-drying | [33] |

| Ropinirole | Carbopol 974P, Guar gum | Solvent evaporation | [34] |

| Quercetin | Methyl-β-cyclodextrin, Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin |

Freeze-drying | [35] |

| Rivastigmine | Ethylcellulose, Chitosan | Emulsion solvent evaporation | [36] |

| FITC-dextrans | Tamarind seed polysaccharide | Spray-drying | [37] |

| Lipid microparticles | |||

| Resveratrol | Tristearin, Glyceryl behenate, Stearic acid | Melt oil/water emulsification |

[38] |

5. Nanoparticles

The great interest in nanoparticles as drug delivery systems is due to numerous advantages such as targeted delivery of drug molecules, greater bioavailability, reduced risk of side effects, etc. [39]. Nanoparticles can incorporate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs and can be used for a variety of administration routes. Inside the nasal cavity, particulates can undertake different pathways according to their size. If the size ranges between 10 and 300 nm, nanoparticles can deliver therapeutic agents through the olfactory pathway directly to the brain, if the size is less than 200 nm, the delivery will occur through clathrin-dependent endocytosis, and if it is in the range from 100 to 200 nm, the transport will occur by caveolae-mediated endocytosis [40]. Certainly, the particle size of the nanocarriers will play a crucial role in achieving brain targeting via the nasal route. However, many other factors, such as carrier type, drug properties, mucoadhesion and swelling capacity, would also be of great importance (Table 2).

| Active Ingredient | Polymer/Lipid | Preparation Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric nanoparticles | |||

| Bromocriptine | Chitosan | Ionic gelation | [41] |

| Ropinirole | Chitosan | Ionic gelation | [42] |

| Rivastigmine | Chitosan | Ionic gelation | [43] |

| Galantamine | Poly (lactic acid), Poly (lactide-co-glycolide) |

Double emulsification of solid-oil-water (s/o/w) |

[44] |

| Huperzine A | Poly (lactide-co-glycolide) | Emulsion solvent evaporation |

[45] |

| Genistein | Chitosan | Ionic gelation | [46] |

| Lipid nanoparticles | |||

| Paenol | Soyabean lecithin | High temperature emulsification/ low-temperature curing |

[47] |

| BACE1 (siRNA) | Solid triglycerides | Emulsion solvent evaporation | [48] |

| Dopamine | Gelucire® 50/13 | Melt emulsification | [49] |

| Pueraria flavones | Borneol, stearic acid | Emulsion solvent evaporation | [50] |

| Pioglitazone | Tripalmitin, MCM, Stearyl amine |

Microemulsification | [51] |

6. Composites

Polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) are a new class of reinforced materials that are formed by the dispersion of nanoscale particles throughout a polymer matrix. Nanocomposites consist of a polymer matrix embedded with nanoparticles to improve a particular property of the material [52]. Researchers span the range from the synthesis of basic structures (such as micro- and nanoparticles functionalized with molecules, simple biomolecules, or polymers) to more complex structures. The main approach initially focused on the control of shape, size, and surface charges, and then on modulating the topology of their chemical composition. At present, many biocompatible and biodegradable polymers have been experimentally and/or clinically investigated for the preparation of polymer-based composites as drug carriers [53]. By designing a composite structure, specific physicochemical and mechanical properties may be obtained. The resulting material may show a combination of its components’ best properties, as well as interesting features that single constituents often do not possess [54]. Examples of polymer micro- and nanoparticulate carriers’ applications for drug delivery in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease models are quite numerous, and they can take advantage of a relatively large number of materials that are biodegradable and suitable for particulate synthesis, including polylactide-co-glycolide (PLGA), polylactic acid (PLA), chitosan (CS), gelatin, polycaprolactone, and polyalkyl cyanoacrylates [55]. Polymeric composites might help to ameliorate the quantity and kinetic release profile of potential and existing Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease drugs. The composite structure should be able, after intranasal application, to stably adhere to outer nasal olfactory epithelium to promote the release of nanoparticles loaded with active molecules. Nanoparticles should then be able to cross the epithelium and migrate to the nervous cells that comprise the olfactory nerve and project to the olfactory bulbs [5][6][7][8]. It is worth noting that the polymeric composite, after residing for a sufficient time to release its nanoparticles, should be degraded and eliminated without discomfort for the patient [56]. At present, composite structures seem to be promising drug-carriers, with numerous advantages over conventional forms, but scholars still need to deepen our knowledge of their properties and the peculiar features that the resulting nanocomposites are able to gain upon their carefully arranged mixture.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines10071706

References

- Kadry, H.; Noorani, B.; Cucullo, L. A blood–brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020, 17, 69.

- Pardridge, W.M. Drug transport across the blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 1959–1972.

- Belur, L.R.; Romero, M.; Lee, J.; Podetz-Pedersen, K.M.; Nan, Z.; Riedl, M.S.; Vulchanova, L.; Kitto, K.F.; Fairbanks, C.A.; Kozarsky, K.F.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Intracerebroventricular, Intrathecal, and Intranasal Routes of AAV9 Vector Administration for Genetic Therapy of Neurologic Disease in Murine Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 618360.

- Yi, X.; Manickam, D.S.; Brynskikh, A.; Kabanov, A.V. Agile delivery of protein therapeutics to CNS. J. Control Release 2014, 190, 637–663.

- Gizurarson, S. Anatomical and histological factors affecting intranasal drug and vaccine delivery. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2012, 9, 566–582.

- Gänger, S.; Schindowski, K. Tailoring Formulations for Intranasal Nose-to-Brain Delivery: A Review on Architecture, Physico-Chemical Characteristics and Mucociliary Clearance of the Nasal Olfactory Mucosa. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 116.

- Yarragudi, S.B.; Kumar, H.; Jain, R.; Tawhai, M.; Rizwan, S. Olfactory Targeting of Microparticles Through Inhalation and Bi-directional Airflow: Effect of Particle Size and Nasal Anatomy. J. Aerosol. Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2020, 33, 258–270.

- Erdő, F.; Bors, L.A.; Farkas, D.; Bajza, Á.; Gizurarson, S. Evaluation of intranasal delivery route of drug administration for brain targeting. Brain Res. Bull. 2018, 143, 155–170.

- Crowe, T.P.; Greenlee, M.H.W.; Kanthasamy, A.G.; Hsu, W.H. Mechanism of intranasal drug delivery directly to the brain. Life Sci. 2018, 195, 44–52.

- Crowe, T.P.; Hsu, W.H. Evaluation of Recent Intranasal Drug Delivery Systems to the Central Nervous System. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 629.

- Fortuna, A.; Alves, G.; Serralheiro, A.; Sousa, J.; Falcão, A. Intranasal delivery of systemic-acting drugs: Small-molecules and biomacromolecules. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 88, 8–27.

- Dahlin, M.; Jansson, B.; Björk, E. Levels of dopamine in blood and brain following nasal administration to rats. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 14, 75–80.

- Born, J.; Lange, T.; Kern, W.; McGregor, G.P.; Bickel, U.; Fehm, H.L. Sniffing neuropeptides: A transnasal approach to the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 514–516.

- Craft, S.; Baker, L.D.; Montine, T.J.; Minoshima, S.; Watson, G.S.; Claxton, A.; Arbuckle, M.; Callaghan, M.; Tsai, E.; Plymate, S.R.; et al. Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A pilot clinical trial. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 29–38.

- Patel, H.; Chaudhari, P.; Gandhi, P.; Desai, B.; Desai, D.; Dedhiya, P.; Vyas, B.; Maulvi, F. Nose to brain delivery of tailored clozapine nanosuspension stabilized using (+)-alpha-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate: Optimization and in vivo pharmacokinetic studies. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 600, 120474.

- Vyas, T.K.; Babbar, A.K.; Sharma, R.K.; Singh, S.; Misra, A. Intranasal Mucoadhesive Microemulsions of Clonazepam: Preliminary Studies on Brain Targeting. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 570–580.

- Vyas, T.K.; Babbar, A.K.; Sharma, R.K.; Singh, S.; Misra, A. Preliminary Brain-targeting Studies on Intranasal Mucoadhesive Microemulsions of Sumatriptan. AAPS PharmSciTech 2006, 7, E49–E57.

- Jayachandra Babu, R.; Dayal, P.; Pawar, K.; Singh, M. Nose-to-brain transport of melatonin from polymer gel suspensions: A microdialysis study in rats. J. Drug Target 2011, 19, 731–740.

- Maiti, S.; Sen, K.K. Introductory Chapter: Drug Delivery Concepts. In Advanced Technology for Delivering Therapeutics; Maiti, S.K., Sen, K.K., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017.

- Rassu, G.; Soddu, E.; Cossu, M.; Gavini, E.; Giunchedi, P.; Dalpiaz, A. Particulate formulations based on chitosan for nose-to-brain delivery of drugs. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 77–87.

- Dalpiaz, A.; Gavini, E.; Colombo, G.; Russo, P.; Bortolotti, F.; Ferraro, L.; Tanganelli, S.; Scatturin, A.; Menegatti, E.; Giunchedi, P. Brain uptake of an anti-ischemic agent by nasal administration of microparticles. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 4889–4903.

- Warnken, Z.; Smyth, H.; Watts, A.; Weitman, S.; Kuhn, J.; Williams, R. Formulation and device design to increase nose to brain drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 35, 213–222.

- Djupesland, G.; Messina, J.; Mahmoud, R. The nasal approach to delivering treatment for brain diseases: An anatomic, physiologic, and delivery technology overview. Ther. Deliv. 2014, 5, 709–733.

- Yang, L.; Alexandridis, P. Physicochemical aspects of drug delivery and release from polymer-based colloids. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 5, 132–143.

- Lengyel, M.; Kállai-Szabó, N.; Antal, V.; Laki, A.J.; Antal, I. Microparticles, Microspheres, and Microcapsules for Advanced Drug Delivery. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 20.

- Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F. Microparticles Used as Drug Delivery Systems. In Smart Colloidal Materials; Richtering, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 133, pp. 15–21.

- Coelho, J.; Ferreira, P.; Alves, P.; Cordeiro, R.; Fonseca, A.; Góis, J.; Gil, M. Drug delivery systems: Advanced technologies potentially applicable in personalized treatments. EPMA J. 2010, 1, 164–209.

- Maaz, A.; Blagbrough, I.S.; De Bank, P.A. In Vitro Evaluation of Nasal Aerosol Depositions: An Insight for Direct Nose to Brain Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1079.

- Cheng, Y.S. Mechanisms of pharmaceutical aerosol deposition in the respiratory tract. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 630–640.

- Ugwoke, M.I.; Agu, R.U.; Verbeke, N.; Kinget, R. Nasal mucoadhesive drug delivery: Background, applications, trends and future perspectives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 1640–1665.

- Gavini, E.; Rassu, G.; Haukvik, T.; Lanni, C.; Racchi, M.; Giunchedi, P. Mucoadhesive microspheres for nasal administration of cyclodextrins. J. Drug Target 2009, 17, 168–179.

- Rassu, G.; Soddu, E.; Cossu, M.; Brundu, A.; Cerri, G.; Marchetti, N.; Ferraro, L.; Regan, R.F.; Giunchedi, P.; Gavini, E.; et al. Solid microparticles based on chitosan or methyl-β-cyclodextrin: A first formulative approach to increase the nose-to-brain transport of deferoxamine mesylate. J. Control Release 2015, 201, 68–77.

- Hussein, N.; Omer, H.; Ismael, A.; Albed Alhnan, M.; Elhissi, A.; Ahmed, W. Spray-dried alginate microparticles for potential intranasal delivery of ropinirole hydrochloride: Development, characterization and histopathological evaluation. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2020, 25, 290–299.

- Mantry, S.; Balaji, A. Formulation design and characterization of ropinirole hydrochoride microsphere for intranasal delivery. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017, 10, 195–203.

- Manta, K.; Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Chountoulesi, M.; Diamantis, D.; Spaneas, D.; Vakali, V.; Naziris, N.; Chatziathanasiadou, M.V.; Andreadelis, I.; Moschovou, K.; et al. Preparation and biophysical characterization of inclusion complexes with β-cyclodextrin derivatives for the preparation of possible nose-to-brain Quercetin delivery systems. Mol. Pharmaceut. 2020, 17, 4241–4255.

- Gao, Y.; Almalki, W.H.; Afzal, O.; Panda, S.K.; Kazmi, I.; Alrobaian, M.; Katouah, H.A.; Altamimi, A.S.A.; Al-Abbasi, F.A.; Alshehri, S.; et al. Systematic development of lectin conjugated microspheres for nose-to-brain delivery of rivastigmine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111829.

- Yarragudi, S.B.; Richter, R.; Lee, H.; Walker, G.F.; Clarkson, A.N.; Kumar, H.; Rizwan, S.B. Formulation of olfactory-targeted microparticles with tamarind seed polysaccharide to improve the transport of drugs. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 163, 216–226.

- Trotta, V.; Pavan, B.; Ferraro, L.; Beggiato, S.; Traini, D.; Des Reis, L.G.; Scalia, S.; Dalpiaz, A. Brain targeting of resveratrol by nasal administration of chitosan-coated lipid microparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 127, 250–259.

- Ong, W.-Y.; Shalini, S.-M.; Constantino, L. Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery by Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Neurological Disorders. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 4247–4256.

- Khan, A.R.; Liu, M.; Khan, M.W.; Zhai, G. Progress in brain targeting drug delivery system by nasal route. J. Control Release. 2017, 268, 364–389.

- Md, S.; Khan, R.A.; Mustafa, G.; Chuttani, K.; Baboota, S.; Sahni, J.K.; Ali, J. Bromocriptine-loaded chitosan nanoparticles intended for direct nose to brain delivery: Pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic and scintigraphy study in mouse model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 48, 393–405.

- Jafarieh, O.; Md, S.; Ali, M.; Baboota, S.; Sahni, J.K.; Kumari, B.; Bhatnagar, A.; Ali, J. Design, characterization, and evaluation of intranasal delivery of ropinirole-loaded mucoadhesive nanoparticles for brain targeting. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2015, 41, 1674–1681.

- Fazil, M.; Md, S.; Haque, S.; Kumar, M.; Baboota, S.; Sahni, J.K.; Ali, J. Development and evaluation of rivastigmine loaded chitosan nanoparticles for brain targeting. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 47, 6–15.

- Nanaki, S.G.; Spyrou, K.; Bekiari, C.; Veneti, P.; Baroud, T.N.; Karouta, N.; Grivas, I.; Papadopoulos, G.C.; Gournis, D.; Bikiaris, D.N. Hierarchical Porous Carbon—PLLA and PLGA Hybrid Nanoparticles for Intranasal Delivery of Galantamine for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 227.

- Meng, Q.; Wang, A.; Hua, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mu, H.; Wu, Z.; Sun, K. Intranasal delivery of Huperzine A to the brain using lactoferrin-conjugated N-trimethylated chitosan surface-modified PLGA nanoparticles for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 705–718.

- Rassu, G.; Porcu, E.P.; Fancello, S.; Obinu, A.; Senes, N.; Galleri, G.; Migheli, R.; Gavini, E.; Giunchedi, P. Intranasal delivery of genistein-loaded nanoparticles as a potential preventive system against neurodegenerative disorders. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 8.

- Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Xie, H.; Wang, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, L.; Bo, F.; Yang, S.; Feng, A. Primary Studies on Construction and Evaluation of Ion-Sensitive in situ Gel Loaded with Paeonol-Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Intranasal Drug Delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 3137–3160.

- Rassu, G.; Soddu, E.; Posadino, A.M.; Pintus, G.; Sarmento, B.; Giunchedi, P.; Gavini, E. Nose-to-brain delivery of BACE1 siRNA loaded in solid lipid nanoparticles for Alzheimer’s therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 152, 296–301.

- Cometa, S.; Bonifacio, M.A.; Trapani, G.; Di Gioia, S.; Dazzi, L.; De Giglio, E.; Trapani, A. In vitro investigations on dopamine loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 185, 113257.

- Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Du, J.; Liu, M.; Feng, J.; Hu, K. Improved brain delivery of pueraria flavones via intranasal administration of borneol-modified solid lipid nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 2105–2119.

- Jojo, G.; Kuppusamy, G.; De, A.; Karri, V. Formulation and optimization of pioglitazone intranasal nanolipid carriers of pioglitazone for the repurposing in Alzheimer’s disease using Box-Behnken design. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2019, 45, 1061–1072.

- Omanović-Mikličanin, E.; Badnjević, A.; Kazlagić, A.; Hajlovac, M. Nanocomposites: A brief review. Health Technol. 2020, 10, 51–59.

- Liechty, W.B.; Kryscio, D.R.; Slaughter, B.V.; Peppas, N.A. Polymers for drug delivery systems. Ann. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2010, 1, 149–173.

- Nicolais, L.; Gloria, A.; Ambrosio, L. The mechanics of biocomposites. In Biomedical Composites, 1st ed.; Ambrosio, L., Ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2010; pp. 411–440.

- Jiang, L.; Gao, L.; Wang, X.; Tang, L.; Ma, J. The application of mucoadhesive polymers in nasal drug delivery. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2010, 36, 323–336.

- Suh, W.H.; Suslick, K.S.; Stucky, G.D.; Suh, Y.H. Nanotechnology, nanotoxicology, and neuroscience. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009, 87, 133–170.