Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) arises directly from pDC over-expansion. BPDCN is a rare hemopathy classified among acute myeloid leukemia (AML) since 2008 by the World Health Organization (WHO). As a specific entity since 2016, it represents <1% of AML. No benchmark treatment exists for BPDCN. Since this rare malignancy is chemo-sensitive, chemotherapy followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation remains an effective treatment. However, relapses frequently occur with the development of resistance. New options arising with the development of therapies targeting signaling pathways and epigenetic dysregulation have shown promising results.

- BPDCN

- conventional therapeutics

- targeted therapies

- chemotherapies

- allogeneic stem cell transplantation

1. ALL Regimen vs. AML and Lymphoma Regimens

2. Allo-HSCT

3. Auto-HSCT

4. BCL-2 Inhibition

5. Epigenetic Dysregulation Targeting

6. Multiple Myeloma-Based Regimens

6.1. NF-κB Inhibition

6.2. CD38 Targeting

7. CD123-Targeted Therapies

7.1. Tagraxofusp

7.2. Other Therapies Targeting CD123

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14153767

References

- Taylor, J.; Haddadin, M.; Upadhyay, V.A.; Grussie, E.; Mehta-Shah, N.; Brunner, A.M.; Louissaint, A.; Lovitch, S.B.; Dogan, A.; Fathi, A.T.; et al. Multicenter Analysis of Outcomes in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm Offers a Pretargeted Therapy Benchmark. Blood 2019, 134, 678–687.

- Yun, S.; Chan, O.; Kerr, D.; Vincelette, N.D.; Idrees, A.; Mo, Q.; Sweet, K.; Lancet, J.E.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Zhang, L.; et al. Survival Outcomes in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm by First-Line Treatment and Stem Cell Transplant. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 3435–3442.

- Laribi, K.; Baugier de Materre, A.; Sobh, M.; Cerroni, L.; Valentini, C.G.; Aoki, T.; Suzuki, R.; Takeuchi, K.; Frankel, A.E.; Cota, C.; et al. Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasms: Results of an International Survey on 398 Adult Patients. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 4838–4848.

- Brüggen, M.-C.; Valencak, J.; Stranzenbach, R.; Li, N.; Stadler, R.; Jonak, C.; Bauer, W.; Porkert, S.; Blaschke, A.; Meiss, F.; et al. Clinical Diversity and Treatment Approaches to Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A Retrospective Multicentre Study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1489–1495.

- Kerr, D.; Sokol, L. The Advances in Therapy of Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2018, 27, 733–739.

- Cernan, M.; Szotkowski, T.; Hisemova, M.; Cetkovsky, P.; Sramkova, L.; Stary, J.; Racil, Z.; Mayer, J.; Sramek, J.; Jindra, P.; et al. Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: First Retrospective Study in the Czech Republic. Neoplasma 2020, 67, 650–659.

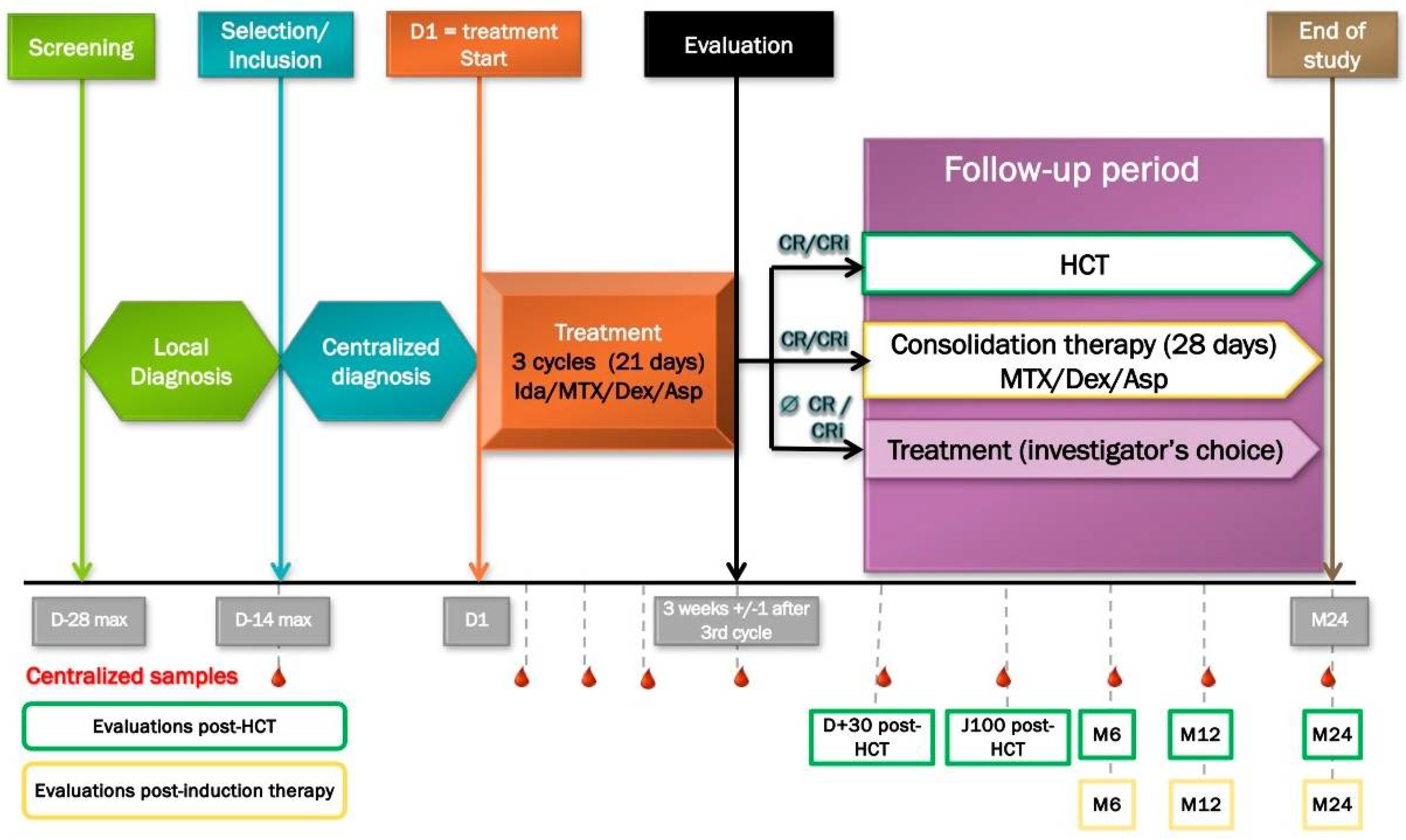

- Garnache-Ottou, F.; Vidal, C.; Biichlé, S.; Renosi, F.; Poret, E.; Pagadoy, M.; Desmarets, M.; Roggy, A.; Seilles, E.; Soret, L.; et al. How Should We Diagnose and Treat Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm Patients? Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 4238–4251.

- Herling, M.; Bröckelmann, P.; Cozzio, A.; Dippel, E.; Dreger, P.; Guenova, E.; Jonak, C.; Manz, M.G.; Oschlies, I.; Reimer, P.; et al. Blastische Plasmazytoide Dendritische Zellneoplasie (BPDCN). Available online: https://www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/blastische-plasmazytoide-dendritische-zellneoplasie-bpdcn/@@guideline/html/index.html (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Gruson, B.; Vaida, I.; Merlusca, L.; Charbonnier, A.; Parcelier, A.; Damaj, G.; Royer, B.; Marolleau, J.-P. L-Asparaginase with Methotrexate and Dexamethasone Is an Effective Treatment Combination in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 163, 543–545.

- Gilis, L.; Lebras, L.; Bouafia-Sauvy, F.; Espinouse, D.; Felman, P.; Berger, F.; Salles, G.; Coiffier, B.; Michallet, A.-S. Sequential Combination of High Dose Methotrexate and L-Asparaginase Followed by Allogeneic Transplant: A First-Line Strategy for CD4+/CD56+ Hematodermic Neoplasm. Leuk. Lymphoma 2012, 53, 1633–1637.

- Fontaine, J.; Thomas, L.; Balme, B.; Ronger-Savle, S.; Traullé, C.; Petrella, T.; Dalle, S. Haematodermic CD4+CD56+ Neoplasm: Complete Remission after Methotrexate-Asparaginase Treatment. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 34, e43–e45.

- Angelot-Delettre, F.; Roggy, A.; Frankel, A.E.; Lamarthee, B.; Seilles, E.; Biichle, S.; Royer, B.; Deconinck, E.; Rowinsky, E.K.; Brooks, C.; et al. In Vivo and in Vitro Sensitivity of Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm to SL-401, an Interleukin-3 Receptor Targeted Biologic Agent. Haematologica 2015, 100, 223–230.

- Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Reljic, T.; Murthy, H.S.; Ayala, E.; Kumar, A. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Is an Effective Treatment for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm in First Complete Remission: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018, 18, 703–709.E1.

- Aoki, T.; Suzuki, R.; Kuwatsuka, Y.; Kako, S.; Fujimoto, K.; Taguchi, J.; Kondo, T.; Ohata, K.; Ito, T.; Kamoda, Y.; et al. Long-Term Survival Following Autologous and Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm. Blood 2015, 125, 3559–3562.

- Montero, J.; Stephansky, J.; Cai, T.; Griffin, G.K.; Cabal-Hierro, L.; Togami, K.; Hogdal, L.J.; Galinsky, I.; Morgan, E.A.; Aster, J.C.; et al. Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm Is Dependent on BCL2 and Sensitive to Venetoclax. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 156–164.

- Grushchak, S.; Joy, C.; Gray, A.; Opel, D.; Speiser, J.; Reserva, J.; Tung, R.; Smith, S.E. Novel Treatment of Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: A Case Report. Medicine 2017, 96, e9452.

- Egger, A.; Coello, D.; Kirsner, R.S.; Brehm, J.E. A Case of Cutaneous Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm Treated with a Bcl-2 Inhibitor. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2021, 20, 550–551.

- Garciaz, S.; Hospital, M.-A.; Alary, A.-S.; Saillard, C.; Hicheri, Y.; Mohty, B.; Rey, J.; D’Incan, E.; Charbonnier, A.; Villetard, F.; et al. Azacitidine Plus Venetoclax for the Treatment of Relapsed and Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Cancers 2022, 14, 2025.

- Labrador, J.; Saiz-Rodríguez, M.; de Miguel, D.; de Laiglesia, A.; Rodríguez-Medina, C.; Vidriales, M.B.; Pérez-Encinas, M.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.J.; Cuello, R.; Roldán-Pérez, A.; et al. Use of Venetoclax in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia: The PETHEMA Registry Experience. Cancers 2022, 14, 1734.

- De Bellis, E.; Imbergamo, S.; Candoni, A.; Liço, A.; Tanasi, I.; Mauro, E.; Mosna, F.; Leoncin, M.; Stulle, M.; Griguolo, D.; et al. Venetoclax in Combination with Hypomethylating Agents in Previously Untreated Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Ineligible for Intensive Treatment: A Real-Life Multicenter Experience. Leuk. Res. 2022, 114, 106803.

- Pollyea, D.A.; DiNardo, C.D.; Arellano, M.L.; Pigneux, A.; Fiedler, W.; Konopleva, M.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Smith, B.D.; Shinagawa, A.; Lemoli, R.M.; et al. Impact of Venetoclax and Azacitidine in Treatment-Naïve Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia and IDH1/2 Mutations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 2753–2761.

- Pollyea, D.A.; Winters, A.; McMahon, C.; Schwartz, M.; Jordan, C.T.; Rabinovitch, R.; Abbott, D.; Smith, C.A.; Gutman, J.A. Venetoclax and Azacitidine Followed by Allogeneic Transplant Results in Excellent Outcomes and May Improve Outcomes versus Maintenance Therapy among Newly Diagnosed AML Patients Older than 60. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022, 57, 160–166.

- DiNardo, C.D.; Rausch, C.R.; Benton, C.; Kadia, T.; Jain, N.; Pemmaraju, N.; Daver, N.; Covert, W.; Marx, K.R.; Mace, M.; et al. Clinical Experience with the BCL2-Inhibitor Venetoclax in Combination Therapy for Relapsed and Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Related Myeloid Malignancies. Am. J. Hematol. 2018, 93, 401–407.

- Cherry, E.M.; Abbott, D.; Amaya, M.; McMahon, C.; Schwartz, M.; Rosser, J.; Sato, A.; Schowinsky, J.; Inguva, A.; Minhajuddin, M.; et al. Venetoclax and Azacitidine Compared with Induction Chemotherapy for Newly Diagnosed Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 5565–5573.

- Kohlhapp, F.J.; Haribhai, D.; Mathew, R.; Duggan, R.; Ellis, P.A.; Wang, R.; Lasater, E.A.; Shi, Y.; Dave, N.; Riehm, J.J.; et al. Venetoclax Increases Intratumoral Effector T Cells and Antitumor Efficacy in Combination with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 68–79.

- Lee, J.B.; Khan, D.H.; Hurren, R.; Xu, M.; Na, Y.; Kang, H.; Mirali, S.; Wang, X.; Gronda, M.; Jitkova, Y.; et al. Venetoclax Enhances T Cell–Mediated Antileukemic Activity by Increasing ROS Production. Blood 2021, 138, 234–245.

- Murakami, S.; Suzuki, S.; Hanamura, I.; Yoshikawa, K.; Ueda, R.; Seto, M.; Takami, A. Combining T-cell-based Immunotherapy with Venetoclax Elicits Synergistic Cytotoxicity to B-cell Lines in Vitro. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 38, 705–714.

- Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Ni, M.; Neuber, B.; Wang, S.; Gong, W.; Sauer, T.; Sellner, L.; Schubert, M.-L.; Hückelhoven-Krauss, A.; et al. Pre-Sensitization of Malignant B Cells Through Venetoclax Significantly Improves the Cytotoxic Efficacy of CD19.CAR-T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 608167.

- Sapienza, M.R.; Abate, F.; Melle, F.; Orecchioni, S.; Fuligni, F.; Etebari, M.; Tabanelli, V.; Laginestra, M.A.; Pileri, A.; Motta, G.; et al. Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm: Genomics Mark Epigenetic Dysregulation as a Primary Therapeutic Target. Haematologica 2019, 104, 729–737.

- Togami, K.; Chung, S.S.; Madan, V.; Booth, C.A.G.; Kenyon, C.M.; Cabal-Hierro, L.; Taylor, J.; Kim, S.S.; Griffin, G.K.; Ghandi, M.; et al. Sex-Biased ZRSR2 Mutations in Myeloid Malignancies Impair Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Activation and Apoptosis. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 522–541.

- Kaminskas, E.; Farrell, A.T.; Wang, Y.-C.; Sridhara, R.; Pazdur, R. FDA Drug Approval Summary: Azacitidine (5-Azacytidine, VidazaTM) for Injectable Suspension. Oncologist 2005, 10, 176–182.

- Togami, K.; Pastika, T.; Stephansky, J.; Ghandi, M.; Christie, A.L.; Jones, K.L.; Johnson, C.A.; Lindsay, R.W.; Brooks, C.L.; Letai, A.; et al. DNA Methyltransferase Inhibition Overcomes Diphthamide Pathway Deficiencies Underlying CD123-Targeted Treatment Resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 5005–5019.

- Sapienza, M.R.; Fuligni, F.; Agostinelli, C.; Tripodo, C.; Righi, S.; Laginestra, M.A.; Pileri, A.; Mancini, M.; Rossi, M.; Ricci, F.; et al. Molecular Profiling of Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm Reveals a Unique Pattern and Suggests Selective Sensitivity to NF-KB Pathway Inhibition. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1606–1616.

- Ceroi, A.; Masson, D.; Roggy, A.; Roumier, C.; Chagué, C.; Gauthier, T.; Philippe, L.; Lamarthée, B.; Angelot-Delettre, F.; Bonnefoy, F.; et al. LXR Agonist Treatment of Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm Restores Cholesterol Efflux and Triggers Apoptosis. Blood 2016, 128, 2694–2707.

- Philippe, L.; Ceroi, A.; Bôle-Richard, E.; Jenvrin, A.; Biichle, S.; Perrin, S.; Limat, S.; Bonnefoy, F.; Deconinck, E.; Saas, P.; et al. Bortezomib as a New Therapeutic Approach for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1861–1868.

- Marmouset, V.; Joris, M.; Merlusca, L.; Beaumont, M.; Charbonnier, A.; Marolleau, J.-P.; Gruson, B. The Lenalidomide/Bortezomib/Dexamethasone Regimen for the Treatment of Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 37, 487–489.

- Mirgh, S.; Sharma, A.; Folbs, B.; Khushoo, V.; Kapoor, J.; Tejwani, N.; Ahmed, R.; Agrawal, N.; Choudhary, P.S.; Mehta, P.; et al. Daratumumab-Based Therapy after Prior Azacytidine-Venetoclax in an Octagenerian Female with BPDCN (Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm)—A New Perspective. Leuk. Lymphoma 2021, 62, 3039–3042.

- Pemmaraju, N.; Konopleva, M. Approval of Tagraxofusp-Erzs for Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 4020–4027.

- Frankel, A.E.; Woo, J.H.; Ahn, C.; Pemmaraju, N.; Medeiros, B.C.; Carraway, H.E.; Frankfurt, O.; Forman, S.J.; Yang, X.A.; Konopleva, M.; et al. Activity of SL-401, a Targeted Therapy Directed to Interleukin-3 Receptor, in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm Patients. Blood 2014, 124, 385–392.

- Pemmaraju, N.; Lane, A.A.; Sweet, K.L.; Stein, A.S.; Vasu, S.; Blum, W.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Wang, E.S.; Duvic, M.; Sloan, J.M.; et al. Tagraxofusp in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic-Cell Neoplasm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1628–1637.

- Lane, A.A.; Stein, A.S.; Garcia, J.S.; Garzon, J.L.; Galinsky, I.; Luskin, M.R.; Stone, R.M.; Winer, E.S.; Leonard, R.; Mughal, T.I.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Combining Tagraxofusp (SL-401) with Azacitidine or Azacitidine and Venetoclax in a Phase 1b Study for CD123 Positive AML, MDS, or BPDCN. Blood 2021, 138, 2346.

- Kovtun, Y.; Jones, G.E.; Adams, S.; Harvey, L.; Audette, C.A.; Wilhelm, A.; Bai, C.; Rui, L.; Laleau, R.; Liu, F.; et al. A CD123-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate, IMGN632, Designed to Eradicate AML While Sparing Normal Bone Marrow Cells. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 848–858.

- Pemmaraju, N.; Martinelli, G.; Todisco, E.; Lane, A.A.; Acuña-Cruz, E.; Deconinck, E.; Wang, E.S.; Sweet, K.L.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Mazzarella, L.; et al. Clinical Profile of IMGN632, a Novel CD123-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC), in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory (R/R) Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm (BPDCN). Blood 2020, 136, 11–13.

- Cai, T.; Galetto, R.; Gouble, A.; Smith, J.; Cavazos, A.; Konoplev, S.; Lane, A.A.; Guzman, M.L.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Pemmaraju, N.; et al. Pre-Clinical Studies of Anti-CD123 CAR-T Cells for the Treatment of Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm (BPDCN). Blood 2016, 128, 4039.

- Mardiros, A.; Dos Santos, C.; McDonald, T.; Brown, C.E.; Wang, X.; Budde, L.E.; Hoffman, L.; Aguilar, B.; Chang, W.-C.; Bretzlaff, W.; et al. T Cells Expressing CD123-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptors Exhibit Specific Cytolytic Effector Functions and Antitumor Effects against Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2013, 122, 3138–3148.

- Bôle-Richard, E.; Fredon, M.; Biichlé, S.; Anna, F.; Certoux, J.-M.; Renosi, F.; Tsé, F.; Molimard, C.; Valmary-Degano, S.; Jenvrin, A.; et al. CD28/4-1BB CD123 CAR T Cells in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm. Leukemia 2020, 34, 3228–3241.

- Loff, S.; Dietrich, J.; Meyer, J.-E.; Riewaldt, J.; Spehr, J.; von Bonin, M.; Gründer, C.; Swayampakula, M.; Franke, K.; Feldmann, A.; et al. Rapidly Switchable Universal CAR-T Cells for Treatment of CD123-Positive Leukemia. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2020, 17, 408–420.

- Riberdy, J.M.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, F.; Kim, Y.-I.; Moore, J.; Vaidya, A.; Throm, R.E.; Sykes, A.; Sahr, N.; Bonifant, C.L.; et al. The Art and Science of Selecting a CD123-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor for Clinical Testing. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 18, 571–581.