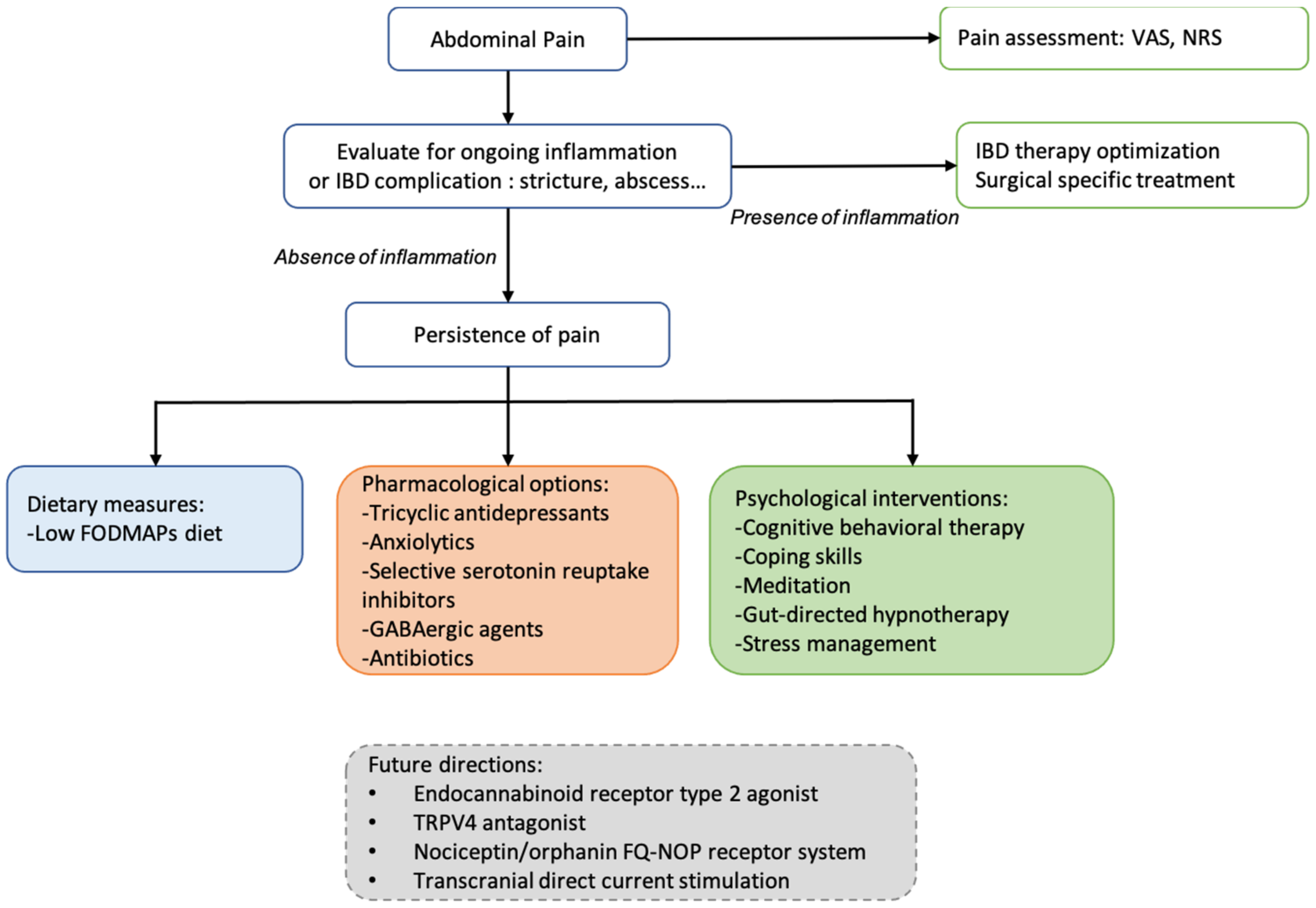

Up to 60% of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients experience abdominal pain in their lifetime regardless of disease activity. Pain negatively affects different areas of daily life and particularly impacts the quality of life of IBD patients. Despite the optimal management of intestinal inflammation, chronic abdominal pain can persist, and pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches are necessary. Integrating psychological support in care models in IBD could decrease disease burden and health care costs. Consequently, a multidisciplinary approach similar to that used for other chronic pain conditions should be recommended.

- inflammatory bowel disease

- abdominal pain

- quality of life

1. Overview

2. Current Pharmacological Options

| Treatment | Study Design | Study Intervention | Age (Year) Sex F |

Number of Patients | Abdominal Pain Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological treatment | |||||

| tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) [14] (nortriptyline, amitriptyline, desipramine, doxepin) |

Retrospective cohort study | IBD patients with inactive or mildly active disease and persistent gastrointestinal symptoms (median TCA dose: 25 mg (10–150 mg)) | 41.3 69% |

58 CD/23 UC | TCA improved gastrointestinal symptoms in 59.3% of IBD patients (Likert score ≥ 2) Response was better in UC than in CD patients (1.86 ± 0.13 vs. 1.26 ± 0.11, respectively, p = 0.003) |

| Antibiotics: metronidazole or ciprofloxacin [17] | RCT | CD patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (confirmed by hydrogen/methane breath and glucose tests) receiving metronidazole 250 mg t.d.s (group A) or ciprofloxacin 500 mg b.d (group B) for 10 days | 39 41% |

29 CD | Improvement of abdominal pain in 50% (group A) and 43% (group B) of cases |

| Transdermal nicotine patch [21] | Randomized double-bind study | Transdermal nicotine (5 or 15 mg) versus placebo in active UC patients; improvement of abdominal pain was a secondary outcome. | 44 43% |

72 UC | Abdominal pain rate on 0–2 scale at 6 weeks was at 0.3 inthe nicotine group and at 0.6 in the placebo group (p = 0.05) |

| Loperamide oxide [22] | Double-blind investigation | Loperamide 1 mg or placebo after passage of each unformed stool for one week | 35 53% |

34 CD | At one week, the investigator’s assessment of the change in abdominal pain was significant for loperamide oxide (p = 0.020) but not for placebo. |

| Cannabis [24] | Monocentric cohort | Consecutive patients with IBD who had used cannabis specifically for the treatment of IBD or its symptoms were compared with those who had not | 36.6 50% (users) |

303 | 17.6% of patients used cannabis to relieve symptoms associated with their IBD. Cannabis improved abdominal pain (83.9%), abdominal cramping (76.8%), joint pain (48.2%), and diarrhea (28.6%), although side effects were frequent. |

| Dietary measures | |||||

| Low-FODMAPs diet [28] | Retrospective telephone survey | IBD patients in remission Improvement of 5 points or more for gastrointestinal symptoms after dietary information on low-FODMAPs diet |

48 39% |

52 CD/20 UC | Approximately 70% of patients were adherent to the low-FODMAPs diet After 3 months, 56% had clinical improvement of abdominal pain (p < 0.02) |

| Psychological approaches | |||||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy [29] | RCT (CBT versus supportive nondirective therapy) | Evaluation of IBD activity (PCDAI and PUCAI) and depression in young patients (after 3-month course of CBT or supportive nondirective therapy | 14.3 46% and 52% |

161 CD and 56 UC | Compared with supportive non-directive therapy, CBT showed a greater reduction in IBD activity (p = 0.04); both psychotherapies decreased rate of depression scale |

| Gut-directed hypnotherapy [30] | RCT hypnotherapy (HPN) versus nondirective discussion | Patients received seven sessions of HPN or nondirective discussion. Evaluation of proportion of participants in each condition that had remained clinically asymptomatic through 52 weeks post treatment |

38 54% |

54 quiescent UC | 68% versus 40% of patients maintaining remission for 1 year (p = 0.04) |

| Stress management program [31] | RCT stress management, self-directed stress management, or conventional medical treatment |

CD patients considered in non-active stage of disease under sulfasalazine Evaluation of symptoms post-treatment |

31.7 64% |

45 CD | Significant decrease in abdominal pain in both stress management arms (14.2% and 6.6% versus 48%) |

3. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

3.1. Dietary Measures

3.2. Psychological Approaches

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm11154269

References

- Panés, J.; Vermeire, S.; Lindsay, J.O.; Sands, B.E.; Su, C.; Friedman, G.; Zhang, H.; Yarlas, A.; Bayliss, M.; Maher, S.; et al. Tofacitinib in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Health-Related Quality of Life in Phase 3 Randomised Controlled Induction and Maintenance Studies. J. Crohns Colitis 2018, 12, 145–156.

- Ghosh, S.; Sanchez Gonzalez, Y.; Zhou, W.; Clark, R.; Xie, W.; Louis, E.; Loftus, E.V.; Panes, J.; Danese, S. Upadacitinib Treatment Improves Symptoms of Bowel Urgency and Abdominal Pain, and Correlates with Quality of Life Improvements in Patients with Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2021, 15, 2022–2030.

- Srinath, A.I.; Walter, C.; Newara, M.C.; Szigethy, E.M. Pain Management in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Insights for the Clinician. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2012, 5, 339–357.

- Regueiro, M.; Greer, J.B.; Szigethy, E. Etiology and Treatment of Pain and Psychosocial Issues in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 430–439.e4.

- Zielińska, A.; Sałaga, M.; Włodarczyk, M.; Fichna, J. Focus on Current and Future Management Possibilities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Related Chronic Pain. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2019, 34, 217–227.

- Norton, C.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; Artom, M.; Sweeney, L.; Hart, A. Systematic Review: Interventions for Abdominal Pain Management in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 115–125.

- Colombel, J.-F.; Shin, A.; Gibson, P.R. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Expert Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 380–390.e1.

- Makharia, G.K. Understanding and Treating Abdominal Pain and Spasms in Organic Gastrointestinal Diseases: Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Biliary Diseases. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 45, S89–S93.

- Haapamäki, J.; Tanskanen, A.; Roine, R.P.; Blom, M.; Turunen, U.; Mäntylä, J.; Färkkilä, M.A.; Arkkila, P.E.T. Medication Use among Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: Excessive Consumption of Antidepressants and Analgesics. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 42–50.

- Targownik, L.E.; Nugent, Z.; Singh, H.; Bugden, S.; Bernstein, C.N. The Prevalence and Predictors of Opioid Use in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1613–1620.

- Camilleri, M.; Lembo, A.; Katzka, D.A. Opioids in Gastroenterology: Treating Adverse Effects and Creating Therapeutic Benefits. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 1338–1349.

- Burr, N.E.; Smith, C.; West, R.; Hull, M.A.; Subramanian, V. Increasing Prescription of Opiates and Mortality in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in England. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 534–541.e6.

- Bakshi, N.; Hart, A.L.; Lee, M.C.; Williams, A.C.D.C.; Lackner, J.M.; Norton, C.; Croft, P. Chronic Pain in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Pain 2021, 162, 2466–2471.

- Iskandar, H.N.; Cassell, B.; Kanuri, N.; Gyawali, C.P.; Gutierrez, A.; Dassopoulos, T.; Ciorba, M.A.; Sayuk, G.S. Tricyclic Antidepressants for Management of Residual Symptoms in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 48, 423–429.

- Walker, E.A.; Gelfand, M.D.; Gelfand, A.N.; Creed, F.; Katon, W.J. The Relationship of Current Psychiatric Disorder to Functional Disability and Distress in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1996, 18, 220–229.

- Frolkis, A.D.; Vallerand, I.A.; Shaheen, A.-A.; Lowerison, M.W.; Swain, M.G.; Barnabe, C.; Patten, S.B.; Kaplan, G.G. Depression Increases the Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Which May Be Mitigated by the Use of Antidepressants in the Treatment of Depression. Gut 2019, 68, 1606–1612.

- Castiglione, F.; Rispo, A.; Di Girolamo, E.; Cozzolino, A.; Manguso, F.; Grassia, R.; Mazzacca, G. Antibiotic Treatment of Small Bowel Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 18, 1107–1112.

- Gatta, L.; Scarpignato, C. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: Rifaximin Is Effective and Safe for the Treatment of Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 604–616.

- Ducrotté, P.; Sawant, P.; Jayanthi, V. Clinical Trial: Lactobacillus Plantarum 299v (DSM 9843) Improves Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 4012–4018.

- Guglielmetti, S.; Mora, D.; Gschwender, M.; Popp, K. Randomised Clinical Trial: Bifidobacterium Bifidum MIMBb75 Significantly Alleviates Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Improves Quality of Life—A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 1123–1132.

- Pullan, R.D.; Rhodes, J.; Ganesh, S.; Mani, V.; Morris, J.S.; Williams, G.T.; Newcombe, R.G.; Russell, M.A.; Feyerabend, C.; Thomas, G.A. Transdermal Nicotine for Active Ulcerative Colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 811–815.

- Van Outryve, M.; Toussaint, J. Loperamide Oxide for the Treatment of Chronic Diarrhoea in Crohn’s Disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 1995, 23, 335–341.

- Swaminath, A.; Berlin, E.P.; Cheifetz, A.; Hoffenberg, E.; Kinnucan, J.; Wingate, L.; Buchanan, S.; Zmeter, N.; Rubin, D.T. The Role of Cannabis in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review of Clinical, Scientific, and Regulatory Information. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 427–435.

- Storr, M.; Devlin, S.; Kaplan, G.G.; Panaccione, R.; Andrews, C.N. Cannabis Use Provides Symptom Relief in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease but Is Associated with Worse Disease Prognosis in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 472–480.

- Naftali, T.; Bar-Lev Schleider, L.; Dotan, I.; Lansky, E.P.; Sklerovsky Benjaminov, F.; Konikoff, F.M. Cannabis Induces a Clinical Response in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: A Prospective Placebo-Controlled Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 1276–1280.e1.

- Irving, P.M.; Iqbal, T.; Nwokolo, C.; Subramanian, S.; Bloom, S.; Prasad, N.; Hart, A.; Murray, C.; Lindsay, J.O.; Taylor, A.; et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group, Pilot Study of Cannabidiol-Rich Botanical Extract in the Symptomatic Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 714–724.

- Stero Biotechs Ltd. A Phase 2a Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and Efficacy of Cannabidiol as a Steroid-Sparing Therapy in Steroid-Dependent Crohn’s Disease Patients. Available online: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04056442 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Gibson, P.R. Use of the Low-FODMAP Diet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 40–42.

- McCormick, M.; Reed-Knight, B.; Lewis, J.D.; Gold, B.D.; Blount, R.L. Coping Skills for Reducing Pain and Somatic Symptoms in Adolescents with IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 2148–2157.

- Keefer, L.; Taft, T.H.; Kiebles, J.L.; Martinovich, Z.; Barrett, T.A.; Palsson, O.S. Gut-Directed Hypnotherapy Significantly Augments Clinical Remission in Quiescent Ulcerative Colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 761–771.

- García-Vega, E.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, C. A Stress Management Programme for Crohn’s Disease. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004, 42, 367–383.

- Camilleri, M.; Boeckxstaens, G. Dietary and Pharmacological Treatment of Abdominal Pain in IBS. Gut 2017, 66, 966–974.

- Barrett, J.S.; Irving, P.M.; Shepherd, S.J.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. Comparison of the Prevalence of Fructose and Lactose Malabsorption across Chronic Intestinal Disorders. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 165–174.

- Cox, S.R.; Prince, A.C.; Myers, C.E.; Irving, P.M.; Lindsay, J.O.; Lomer, M.C.; Whelan, K. Fermentable Carbohydrates Exacerbate Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-over, Re-Challenge Trial. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 1420–1429.

- Szigethy, E.; Bujoreanu, S.I.; Youk, A.O.; Weisz, J.; Benhayon, D.; Fairclough, D.; Ducharme, P.; Gonzalez-Heydrich, J.; Keljo, D.; Srinath, A.; et al. Randomized Efficacy Trial of Two Psychotherapies for Depression in Youth with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 726–735.

- Gerbarg, P.L.; Jacob, V.E.; Stevens, L.; Bosworth, B.P.; Chabouni, F.; DeFilippis, E.M.; Warren, R.; Trivellas, M.; Patel, P.V.; Webb, C.D.; et al. The Effect of Breathing, Movement, and Meditation on Psychological and Physical Symptoms and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2886–2896.

- Mikocka-Walus, A.; Bampton, P.; Hetzel, D.; Hughes, P.; Esterman, A.; Andrews, J.M. Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: 24-Month Data from a Randomised Controlled Trial. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 127–135.

- Maunder, R.G.; Levenstein, S. The Role of Stress in the Development and Clinical Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Epidemiological Evidence. Curr. Mol. Med. 2008, 8, 247–252.

- Berger, A.A.; Liu, Y.; Jin, K.; Kaneb, A.; Welschmeyer, A.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.D.; Imani, F.; Khademi, S.-H.; Varrassi, G.; et al. Efficacy of Acupuncture in the Treatment of Chronic Abdominal Pain. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021, 11, e113027.