Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Chemistry, Inorganic & Nuclear

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are continuing to gain popularity in the field of nanotechnology. New methods are continuously being developed to tune the particles’ physicochemical properties, resulting in control over their biological fate and applicability to in vivo diagnostics and therapy. The common methods of synthesizing ultrasmall AuNPs are presented.

- ultrasmall-in-nano

- gold nanoparticles

- clearance

1. Introduction

Colloidal gold is the subject of ever-growing interest in the field of nanotechnology. This is due to its versatility and tunability in terms of size, shape, and surface chemistry. With a rigorous understanding of the properties of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) comes the ability to exploit them for a plethora of therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Almost any material will display three distinct size-dependent ranges of properties, in their atomic-, nano-, and bulk-scale [1]. Thus, most materials can feasibly exist as a ‘nanomaterial’ between 1 and 1000 nanometers; however, to be of any practical use, its properties must be precisely and reproducibly manipulated at scale and, under this criteria, AuNPs excel. Various methods (chemical and physical) have been developed to accurately control AuNP’s size (from 1 to 330 nm), shape (spheres, rods, stars, plates, cubes, cages, and shells), surface chemistry, and optical-electronic properties. Furthermore, AuNPs are inert, non-toxic, and can be made to be stable in a range of solvents and pH values, properties which are desirable from a biological standpoint [2].

With progress into the tunability of almost every aspect of AuNPs comes the opportunity to investigate how varying each one of these properties independently will affect the physicochemical properties and biological outcome of the particles. One of the easiest and most effective ways to control the properties of AuNPs is by varying the size. There are advantages and disadvantages for AuNPs in both the ultrasmall (<5 nm) and the nano (5–1000 nm) size range, in terms of the optical properties, cellular uptake, opsonization, toxicity, biodistribution, tumor accumulation, and excretability [1].

2. Methods to Synthesize Ultrasmall AuNPs

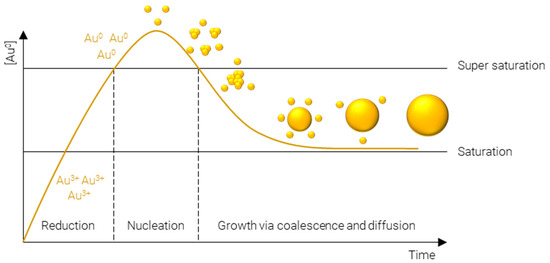

A plethora of methods have been developed to precisely control the size, shape, and surface chemistry of AuNPs. These range from green synthesis methods, where the AuNPs are produced either by microorganisms or plant extracts [56,57,58], to physical methods such as laser ablation [59,60,61], thermal decomposition [62,63], and mechanical milling [64], and finally, chemical synthesis methods. Chemical synthesis methods are perhaps the most widely employed methods, owing to the vast array of physicochemical properties which can be achieved and the specificity with which they can be obtained. Many approaches exist to chemically synthesize AuNPs; however, they all proceed via essentially the same steps (Figure 1):

Figure 1. LaMer model of metal nanoparticle formation.

-

Reduction of Au3+—afforded by a gold salt, usually HAuCl4—to atomic Au0; this process is rapid and continues until the concentration of gold atoms in solution reaches supersaturation.

-

Nucleation of gold atoms into gold clusters; the number of nucleation sites determines the number concentration of AuNPs, i.e., for a fixed mass concentration more nucleation events results in smaller particles and vice versa.

-

Growth via coalescence of gold clusters and diffusion of remaining soluble gold atoms onto the surface of gold agglomerates.

The following sections will outline some of the most common methods used to synthesize ultrasmall AuNPs; they have been divided into the four main methods used in the literature—Turkevich/Frens, reduction by sodium borohydride, Brust–Schiffrin, and seeded growth. Where reagent names have been abbreviated, the meaning can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Abbreviations for reagents use in AuNP synthesis.

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| BDAC | Benzyldimethylhexadecylammonium chloride |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| CTAC | Cetyltrimethylammonium chloride |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HAuCl4 | Chloroauric acid |

| HQL | 8-hydroxyquinoline |

| MPA | Mercaptopropionic acid |

| NaBH4 | Sodium borohydride |

| NaI | Sodium iodide |

| ODA | Octadecylamine |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| TOAB | Tetraoctylammonium bromide |

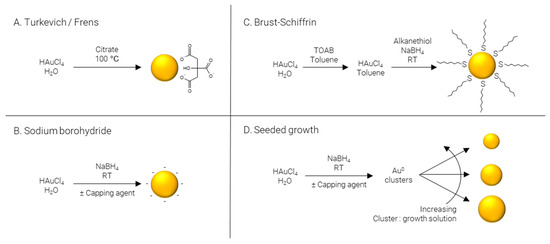

Turkevich/Frens (Figure 2A) synthesis is the classical method of producing AuNPs. It was one of the first systematic approaches to the size-controlled synthesis of AuNPs and is still popular today, owing largely to its simplicity and reliability. The method was pioneered Turkevich et al. in 1951 [65], producing 15–24 nm AuNPs, and later refined by Frens in 1973 [66], extending the size range to 16–147 nm. In this synthesis, citrate is used as both reducing agent and capping agent; however, citrate is not a strong enough reducing agent to rapidly generate atomic gold at room temperature; therefore, the synthesis is carried out at elevated temperature, typically boiling. The AuNPs’ size is controlled predominantly by the ratio of citrate:Au, where more citrate results in more rapid nucleation and, subsequently, smaller particles. Particle size and distribution may also be controlled by pH [67], temperature [68], and order of reagent addition [69]. While AuNPs with an average diameter of 4 nm have been reportedly synthesized by the Turkevich method with minor modifications [70], it is far more common for particles to be larger than 10 nm in diameter.

Figure 2. Methods of AuNP synthesis.

Sodium borohydride (Figure 2B) is often implemented as a strong reducing agent in the synthesis of AuNPs enabling the reaction to be performed at room temperature and allowing for rapid nucleation and formation of smaller AuNPs, frequently sub 5 nm. Like the Turkevich method, citrate may be included; however, when NaBH4 is used as a reducing agent, citrate severs solely as a capping agent [71]. Alternatively, citrate can be replaced by other hydrophilic capping agents such as alginate [72] or chitosan [73]. The synthesis may also be performed in non-polar solvents such as chloroform, implementing hydrophobic capping agents such as CTAB [74] and ODA [75,76]. Finally, capping agents may be omitted entirely to produce “bare” AuNPs [77].

Brust–Schiffrin (Figure 2C) synthesis is a two-phase approach to produce alkanethiol-capped AuNPs which are soluble in hydrophobic solvents. TOAB is employed to transfer AuCl4- from the aqueous phase to an organic phase, typically toluene; NaBH4 is used to reduce the gold salt in the presence of a capping agent, traditionally an alkanethiol. The capping agent first used, and still commonly used today, is the alkanethiol dodecanethiol [78]; however, this may be replaced with other alkanethiols such as pentanethiol [79] or hexanethiol [80], surfactants such as CTAB or CTAC [81], or even ionizable molecules for the synthesis of water soluble AuNPs, for example via the use of MPA [82].

Seeded growth (Figure 2D) is synthetic process of first producing Au0 clusters, often via NaBH4, although Turkevich/Frens particles may also be used as seeds, which are then introduced as presynthesized nuclei into a growth solution. Essentially, the particle number concentration of the resulting solution can be finely controlled by varying the number of nuclei introduced and the final particle size is regulated by the gold concentration in the growth solution. This approach is not particularly well suited to the formation of ultrasmall AuNPs and is more commonly employed for the preparation of particles over a large size range [83,84]. As well as being applicable over large size ranges, seeded growth is also capable of producing a wide variety of shapes by using different shape directing agents, such as CTAC for spheres [85] and cubes [86], CTAC/NaI for triangles [87], CTAB/CTAC/HQL for bipyramids/javelins [88], PVP for stars [89], and BDAC/CTAB for rods [90].

The methods outlined in the previous sections are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Methods of AuNP Synthesis. Focusing mainly on ultrasmall spheres, with several prominent examples of methods for synthesizing larger or non-spherical particles.

| Method of Synthesis | Size Range | Shape | Surface Chemistry | Polarity | Solvent | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkevich | 15–24 nm | Sphere | Citrate | Hydrophilic | H2O | [65] |

| Frens | 16–147 nm | Sphere | Citrate | Hydrophilic | H2O | [66] |

| Turkevich/Frens | 4 nm | Sphere | Citrate | Hydrophilic | H2O | [70] |

| Sodium borohydride | 3–5 nm | Sphere | Citrate | Hydrophilic | H2O | [71] |

| Sodium borohydride | 3.3–12 | Sphere | Alginate | Hydrophilic | H2O | [72] |

| Sodium borohydride | 3.5–14 nm | Sphere | Chitosan | Hydrophilic | H2O | [73] |

| Sodium borohydride | 3–14 nm | Sphere | CTAB | Hydrophobic | CHCl3 | [74] |

| Sodium borohydride | 4.7 nm | Sphere | ODA | Hydrophobic | CHCl3 | [75] |

| Sodium borohydride | 3 nm | Sphere | ODA | Hydrophobic | CHCl3 | [76] |

| Sodium borohydride | 3–5 nm | Sphere | Bare | Hydrophilic | H2O | [77] |

| Turkevich/Frens—modified | 3.6–13 nm | Sphere | Citrate/tannic acid | Hydrophilic | H2O | [91] |

| Turkevich/Frens—modified | 3.5–15 nm | Sphere | PDEAEM | Hydrophilic | H2O | [92] |

| Turkevich/Frens—modified | 2–330 nm | Sphere | Citrate | Hydrophilic | H2O | [93] |

| Brust-Schiffrin | 1–3 nm | Sphere | Dodecanethiol | Hydrophobic | Toluene | [78] |

| Brust-Schiffrin | 5 nm | Sphere | Pentanethiol | Hydrophobic | Toluene | [79] |

| Brust-Schiffrin | 2 nm | Sphere | Hexanethiol | Hydrophobic | Toluene | [80] |

| Brust-Schiffrin | 10 nm | Sphere | CTAB/CTAC | Hydrophobic | Toluene | [81] |

| Brust-Schiffrin | 3 nm | Sphere | MPA | Variable | Toluene/H2O | [82] |

| Seeded growth | 8.4–180.5 nm | Sphere | Citrate | Hydrophilic | H2O | [83] |

| Seeded growth | 15–300 nm | Sphere | Citrate | Hydrophilic | H2O | [84] |

| Seeded growth | 5–150 | Sphere | CTAC | Hydrophilic | H2O | [85] |

| Seeded growth | 60 nm | Triangle | CTAC/NaI | Hydrophilic | H2O | [87] |

| Seeded growth | 76 nm | Cube | CTAC | Hydrophilic | H2O | [86] |

| Seeded growth | 40–300 nm | Bipyramid/Javelin | CTAB/CTAC/HQL | Hydrophilic | H2O | [88] |

| Seeded growth | 45–116 nm | Star | PVP | Hydrophilic | DMF | [89] |

| Seeded growth | 10–100 nm | Rod | BDAC/CTAB | Hydrophilic | H2O | [90] |

| Other—GSH reduction | 2.5 nm | Sphere | GSH | Hydrophilic | H2O | [94] |

| Other—GSH reduction | 2.3 nm | Sphere | GSH/cysteamine | Hydrophilic | H2O | [95] |

| Other—HEPES reduction | 23 nm | Star | HEPES | Hydrophilic | H2O | [96] |

| Other—TBAB reduction | 2–7 nm | Sphere | Oleylamine | Hydrophobic | DCM | [97] |

| Other—TBAB reduction | 3–10 nm | Sphere | Oleylamine | Hydrophobic | Hexane | [98] |

| Other—thermal reduction | 2 nm | Sphere | PEG | Hydrophilic | H2O | [99] |

| Other—mechanochemical | 1–4 nm | Sphere | Various | Various | None | [64] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nano12142476

References

- Ryan D. Mellor; Ijeoma F. Uchegbu; Ultrasmall-in-Nano: Why Size Matters. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2476, 10.3390/nano12142476.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!