Primary cilia are sensory organelles present on the surface of most polarized cells. Primary cilia have been demonstrated to play many sensory cell roles, including mechanosensory and chemosensory cell functions. It is known that the primary cilia of vascular endothelial cells will bend in response to fluid shear stress, which leads to the biochemical production and release of nitric oxide, and this process is impaired in endothelial cells that lack primary cilia function or structure. In this entry, we will provide an overview of ciliogenesis and the differences between primary cilia and multicilia, as well as an overview of our published work on primary cilia and nitric oxide, and a brief perspective on their implications in health and disease.

This entry is adapted (and updated) from: Ley, S. T., & AbouAlaiwi, W. A. (2019). Primary Cilia are Sensory Hubs for Nitric Oxide Signaling. In K. F. Shad, S. S. S. Saravi, & N. L. Bilgrami (Eds.), Basic and Clinical Understanding of Microcirculation. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.89680

- primary cilia

- nitric oxide

- signaling

- fluid shear stress

- mechanosensory transduction

1. Introduction

Cilia are found in nearly every cell in the animal body, where they function as highly specialized sensory organelles. Ciliary malfunction, therefore, tends to result in severe abnormalities, which are often multisystemic. These abnormalities are known as ciliopathies, and as our understanding of cilia form and function continues to grow, so too does the list of known ciliopathies. It is now known that mutations in over 40 genes can alter cilia structure or function, and this list continues to grow; over 1000 polypeptides in the ciliary proteome have yet to be researched[1][2].

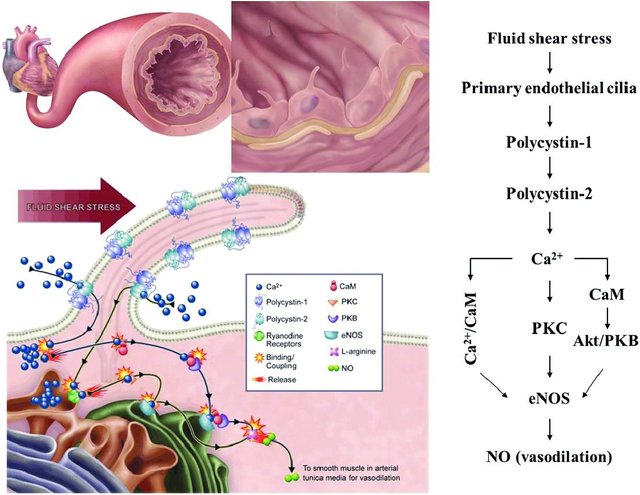

The field of cilia research gained interest after the discovery that cilia play a role in the pathogenesis of polycystic kidney disease (PKD) as fluid mechanosensors within the kidney. In addition to renal dysfunction, the cardiovascular system is also affected by PKD, which has prompted further research into the role which primary cilia play within this system. In kidney tubule epithelia, primary cilia activation leads to a calcium influx, and it has been proposed that this may also occur in vascular endothelial cells. In their study, Nauli et al. showed that vascular cilia play a similar function in sensing fluid shear stress, and there was a corresponding increase in calcium levels correlated with nitric oxide (NO) release. This is thought to contribute to blood pressure control directly. Testing this hypothesis, Nauli et al. showed that cilia mutant cell lines had little to no calcium influx, as well as a lack of NO release while under fluid shear stress[1][3][4].

Nitric oxide is a signaling molecule that plays many important functional roles in almost every organ system in the body. Various pathologies are associated with wayward NO production and altered bioavailability levels caused by abnormal signaling cascades, which are often the result of abnormal cilia-regulated signaling pathways. There is a documented connection between cilia and NO in the vasculature, as well as an overlap between signaling pathways in other pathologies. It has been postulated that there is a connection between primary cilia and NO outside of the vasculature, but literature on the subject is scarce. This entry aims to explain cilia type, structure, and function, as well as ciliogenesis, nitric oxide signaling, and finally the interplay between nitric oxide and primary cilia.

2. Cilia type and structure

To understand what makes primary cilia unique, it is important to understand the differences between cilia form and function. Cilia are dynamic sensory organelles present in nearly every cell in every animal, as well as most protozoa. There are two classes of cilia; motile, which possess the dynein motor complexes needed to move, and nonmotile. Motile and nonmotile cilia both contain a 25 μm diameter cytoskeletal scaffold known as the axoneme. The axoneme is comprised of hundreds of proteins and houses nine peripheral microtubule doublets. These doublets are made up of A and B tubules, and they either surround a central pair of microtubules (9 + 2 pattern), or do not (9 + 0 pattern)[5]. Some motile cilia contain a 9 + 2 pattern and exist in clusters on cells called multiciliated cells (MCCs)[6]. There is also a class of motile cilia that have a 9 + 0 structure and exist as solitary monocilia on cell surfaces. The presence or absence of the central pair leads to significant functional differences in the cilia. The 9 + 2 structure commonly moves in a wave-like motion to move fluid, and an example of this are the ependymal cilia. The 9 + 2 patterned cilia also move cerebral spinal fluid, while the 9 + 0 structured most commonly moves in a rotary or corkscrew motion, as seen in flagella, which is useful for propulsion[7][8]. There is some debate on whether sperm tail flagella should be classified as motile monocilia; regardless, they also possess a similar axonemal structure[5][6][9][10][11]. Nonmotile cilia, known as primary cilia, have a 9 + 0 structure and exist as monocilia on the surface of cells. As primary cilia can be found on vascular endothelial cells, they will be the focus of this entry, but a brief overview of multicilia and their motion will also be covered.

2.1 Ciliogenesis

Cilia formation is known as ciliogenesis. Ciliogenesis is correlated with cell division and occurs at the G1/G0 phase of the cell cycle. Reabsorption or disassembly of the cilium starts after cell cycle re-entry. In the first step of ciliogenesis, the centrosome travels to the cell surface, whereupon a basal body is formed by the mother centriole, and it nucleates the ciliary axoneme at the G1/G0 phase of the cell cycle [12]. This first process is regulated by distal appendage proteins, such as centrosomal protein 164[13]. During the second step, the cilium elongates; this process is regulated by nuclear distribution gene E homolog 1 (Nde1), up until the cilium is matured[14]. The third step is cilia resorption, followed by axonemal shortening during cell cycle reentry. This third process is controlled by the Aurora A-HDAC6, Nek2-Kif24, and Plk1-Kif2A pathways[15]. In the fourth step, the basal body is released from the cilia, which frees the centrioles that act as microtubule organizing centers or spindle poles for mitosis[12].

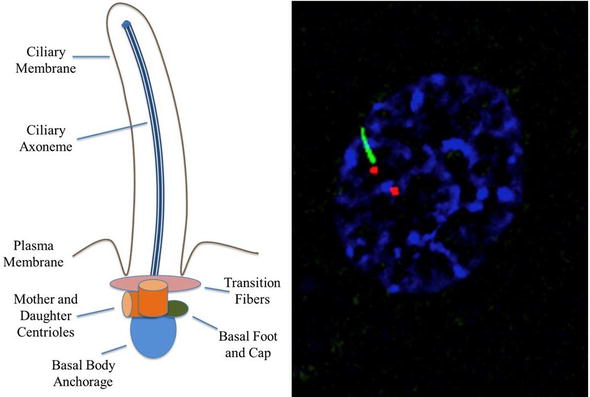

Immotile cilia formation is impacted by the coordination of the assembly and disassembly equilibrium, the IFT system, and membrane trafficking. When the axoneme nucleates from the basal body, it contains a microtubule bundle contained within the ciliary membrane [16]. Enclosed within are certain signaling molecules and ion channels. Because cilia lack the machinery needed to synthesize ciliary proteins, proteins synthesized by the cell’s Golgi apparatus must be transported through a ciliary ‘gate’ and transition zone near the cilium base[17]. The transition zone, recognizable by a change from triplet to doublet microtubules, is located at the distal end of the basal body (Figure 1)[18]. Basal body docking with the plasma membrane can be either permanent, in the case of unicellular organisms, or temporary, in the case of metazoans[5].

Transition fibers, which are present in unicellular organisms, or distal and subdistal appendages, which are present in mammals, are attached to microtubules within the transition zone[19]. Transition fibers function as docking sites for intraflagellar transport (IFT) proteins[20]. IFT transports cargo in a bidirectional manner along the length of cilia and is mediated by kinesin-2 (anterograde) and cytoplasmic dynein-2 motors (retrograde) attached to multisubunit protein complexes known as IFT particles[21][22]. Y-linkers exist at the distal end of the transition zone and secure the doublet microtubules to the ciliary membrane in most organisms[19].

2.2 Multicilia

In vertebrates, MCCs are present in a wide variety of different tissue types. In mammals, ependymal MCCs line brain ventricles and the airway epithelium. Multicilia are produced by specialized cells for highly specialized functions. MCCs are typically defined as having more than two cilia on their surface, although this occurrence is not well documented or understood. Recently, MCCs have been observed in unicellular eukaryotes and protists, as well as many metazoans, and even in certain plant sperms [23][24][25]. MCCs result in the production of motile axonemes, with the only notable exception being mammalian olfactory cilia. These olfactory MCCs lack dynein arms and are considered immotile despite having a 9 + 2 structure. This occurrence is indicative of MCCs being a solution to the need for local fluid flow, possibly due to their ability for hydrodynamic coupling [6][26][27].

Multicilia carry out their functions by beating, and the basic machinery and organization of cilia beating seems well conserved between eukaryotes, as well as between single motile cilium and multicilia. Some parameters, such as beat frequency, are under cellular control and are varied among cell types. In addition, only motile cilia and sperm flagella contain the dynein machinery needed to power axonemal beating during ATP hydrolysis[5][28]. The ciliary beat cycle has two phases: the effective stroke, and the recovery stroke. The effective stroke is the initially bending from its upright position, while the recovery stroke sees it return to its original, unbent position. Ciliary motility is controlled by outer and inner axonemal dynein arms, which slide adjacent doublets in respect to one another. The sliding is mediated by protein bridges between doublets, and by the basal anchoring of the axoneme. As a result, cilia bend[6][29]. The phenomenon metachrony occurs when cilia are organized in such a way that each cilium, in a two-dimensional array, will beat at the same frequency, but in a phase shifted manner. As a result, a traveling wave of ciliary action moves across the array, which propels fluids in a current. Even if each cilium in an array starts off in synch, hydrodynamic forces between each cilium will nudge them back towards metachrony, possibly because in a metachronal array, the work each cilium must do is reduced, and more fluid is displaced. Because of this, multiciliation is thought to be a more evolutionarily efficient way to generate fluid flow[6][30][31][32].2.3 Primary cilia

vestigial organelle[33].

The ciliary membrane is an extension of the cellular membrane where a host of proteins and receptors are housed due to the ciliary transition zone, which provides docking sites for molecular transport into and out of the cilioplasm (Figure 1)[38][39][40]. While there is no confirmed mechanism by which molecules enter and exit the cilia, several mechanisms have been proposed. One such mechanism is the active transport of vesicles from the Golgi apparatus to docking sites in the transition zone[41]. The vesicles are thought to interact with exocyst complexes, where they experience soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) attachment protein receptor (SNARE) mediated diffusion across the cilioplasm/cytoplasm barrier[37]. The BBSome, which resides in the basal body and is an octameric protein complex, is involved in the movement of transmembrane proteins to the ciliary membrane. BBSomes are known to recognize ciliary targeting sequences and will readily interact with molecules that are upstream of Rab8 activation. BBSomes are not thought to be required for any aspect of ciliogenesis; nevertheless, if BBSomes fail to deliver certain vital proteins to the cilia, the cilia may lose functionality[42][43][44][45]. Another proposed mechanism of molecule trafficking is the action of transmembrane proteins, of which some are associated with specific protein sequences that target cilia localization, such as the N-terminal RVxP sequence on polycystin-2 (PC-2)[42][46].

3. Nitric oxide

4. Cilia and nitric oxide interplay

4.1 Vasodilation

bidirectionally between the cilia and the cytosol[57][58][59]. Regardless, the increase in intracellular calcium triggers the calcium/calmodulin complex, which activates constitutive NOS, such as eNOS, by binding to its target site on the enzyme[60].

4.2 Wound healing

4.3 Dopamine signaling

reversed with dopamine treatment; but when haloperidol, a D2 selective antagonist drug, was administered, the vasorelaxation failed to occur. It was also reported that, after administration of dopamine, a large increase in eNOS and iNOS expression was seen, and administration of haloperidol also blocked this effect[79].

those without ADPKD. When ADPKD patients were administered brachial infusions of 0.25–0.5 μg/kg/min of dopamine, there was an increase in flow-mediated dilation, and a statistically significant increase in dilatory response at the highest dose[80]. According to these results, dopamine receptors may facilitate a connection between primary cilia, NO, and blood pressure regulation in ADPKD patients.

4.4 Cell proliferation

5. Conclusion

References

- Hannah C. Saternos; Wissam A. AbouAlaiwi; Signaling interplay between primary cilia and nitric oxide: A mini review. Nitric Oxide 2018, 80, 108-112, 10.1016/j.niox.2018.08.003.

- Aoife M. Waters; Philip L. Beales; Ciliopathies: an expanding disease spectrum. Pediatric Nephrology 2011, 26, 1039-1056, 10.1007/s00467-010-1731-7.

- Surya M. Nauli; Yoshifumi Kawanabe; John J. Kaminski; William J. Pearce; Donald E. Ingber; Jing Zhou; Endothelial Cilia Are Fluid Shear Sensors That Regulate Calcium Signaling and Nitric Oxide Production Through Polycystin-1. Circulation 2008, 117, 1161-1171, 10.1161/circulationaha.107.710111.

- Wissam A. AbouAlaiwi; Maki Takahashi; Blair R. Mell; Thomas J. Jones; Shobha Ratnam; Robert J. Kolb; Surya M. Nauli; Ciliary Polycystin-2 Is a Mechanosensitive Calcium Channel Involved in Nitric Oxide Signaling Cascades. Circulation Research 2009, 104, 860-869, 10.1161/circresaha.108.192765.

- Hannah M. Mitchison; Enza Maria Valente; Motile and non-motile cilia in human pathology: from function to phenotypes. The Journal of Pathology 2016, 241, 294-309, 10.1002/path.4843.

- Eric R. Brooks; John B. Wallingford; Multiciliated Cells. Current Biology 2014, 24, R973-R982, 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.047.

- Alzahra J. Al Omran; Hannah C. Saternos; Yusuf Althobaiti; Alexander Wisner; Youssef Sari; Surya M. Nauli; Wissam A. AbouAlaiwi; Alcohol consumption impairs the ependymal cilia motility in the brain ventricles. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1-8, 10.1038/s41598-017-13947-3.

- Shigenori Nonaka; Hidetaka Shiratori; Yukio Saijoh; Hiroshi Hamada; Determination of left–right patterning of the mouse embryo by artificial nodal flow. Nature 2002, 418, 96-99, 10.1038/nature00849.

- Iben R. Veland; Aashir Awan; Lotte B. Pedersen; Bradley K. Yoder; Søren T. Christensen; Primary Cilia and Signaling Pathways in Mammalian Development, Health and Disease. Nephron 2009, 111, p39-p53, 10.1159/000208212.

- O Arnaiz; J Cohen; Am Tassin; F Koll; Remodeling Cildb, a popular database for cilia and links for ciliopathies. Cilia 2015, 4, P21-P21, 10.1186/2046-2530-4-s1-p21.

- Gregory Pazour; Nathan Agrin; John Leszyk; George B. Witman; Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. Journal of Cell Biology 2005, 170, 103-113, 10.1083/jcb.200504008.

- Prachee Avasthi; Wallace F. Marshall; Stages of ciliogenesis and regulation of ciliary length. Differentiation 2012, 83, S30-S42, 10.1016/j.diff.2011.11.015.

- Susanne Graser; York-Dieter Stierhof; Sébastien B. Lavoie; Oliver S. Gassner; Stefan Lamla; Mikael Le Clech; Erich A. Nigg; Cep164, a novel centriole appendage protein required for primary cilium formation. Journal of Cell Biology 2007, 179, 321-330, 10.1083/jcb.200707181.

- Sehyun Kim; Norann A. Zaghloul; Ekaterina Bubenshchikova; Edwin C. Oh; Susannah Rankin; Nicholas Katsanis; Tomoko Obara; Leonidas Tsiokas; Nde1-mediated inhibition of ciliogenesis affects cell cycle re-entry. Nature Cell Biology 2011, 13, 351-360, 10.1038/ncb2183.

- Vladislav Korobeynikov; Alexander Y. Deneka; Erica A. Golemis; Mechanisms for nonmitotic activation of Aurora-A at cilia. Biochemical Society Transactions 2017, 45, 37-49, 10.1042/bst20160142.

- Sarah C. Goetz; Kathryn Anderson; The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nature Reviews Genetics 2010, 11, 331-344, 10.1038/nrg2774.

- Jeremy F Reiter; Oliver E Blacque; Michel R Leroux; The base of the cilium: roles for transition fibres and the transition zone in ciliary formation, maintenance and compartmentalization. EMBO reports 2012, 13, 608-618, 10.1038/embor.2012.73.

- Huawen Lin; Suyang Guo; Susan K. Dutcher; RPGRIP1L helps to establish the ciliary gate for entry of proteins. Journal of Cell Science 2017, 131, na, 10.1242/jcs.220905.

- Cathy Fisch; Pascale Dupuis-Williams; Ultrastructure of cilia and flagella - back to the future!. Biology of the Cell 2011, 103, 249-270, 10.1042/bc20100139.

- James A. Deane; Douglas G. Cole; E.Scott Seeley; Dennis R. Diener; Joel L. Rosenbaum; Localization of intraflagellar transport protein IFT52 identifies basal body transitional fibers as the docking site for IFT particles. Current Biology 2001, 11, 1586-1590, 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00484-5.

- Lotte B. Pedersen; Joel L. Rosenbaum; Chapter Two Intraflagellar Transport (IFT). null 2007, 85, 23-61, 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)00802-8.

- Michael Taschner; Esben Lorentzen; The Intraflagellar Transport Machinery. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2016, 8, a028092, 10.1101/cshperspect.a028092.

- Ikuko Mizukami; Joseph Gall; CENTRIOLE REPLICATION. Journal of Cell Biology 1966, 29, 97-111, 10.1083/jcb.29.1.97.

- Matthew E. Hodges; Bill Wickstead; Keith Gull; Jane A. Langdale; The evolution of land plant cilia. New Phytologist 2012, 195, 526-540, 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04197.x.

- Claus Nielsen; Structure and Function of Metazoan Ciliary Bands and Their Phylogenetic Significance. Acta Zoologica 1987, 68, 205-262, 10.1111/j.1463-6395.1987.tb00892.x.

- Michael S. Lidow; Bert Ph.M. Menco; Observations on axonemes and membranes of olfactory and respiratory cilia in frogs and rats using tannic acid-supplemented fixation and photographic rotation. Journal of Ultrastructure Research 1984, 86, 18-30, 10.1016/s0022-5320(84)90092-3.

- Peter Satir; Søren Tvorup Christensen; Overview of Structure and Function of Mammalian Cilia. Annual Review of Physiology 2007, 69, 377-400, 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141236.

- Stephen M. King; Axonemal Dynein Arms. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2016, 8, a028100, 10.1101/cshperspect.a028100.

- Ramin Golestanian; Julia M. Yeomans; Nariya Uchida; Hydrodynamic synchronization at low Reynolds number. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 3074-3082, 10.1039/c0sm01121e.

- H Machemer; Ciliary activity and the origin of metachrony in Paramecium: effects of increased viscosity.. Journal of Experimental Biology 1972, 57, 239-59, .

- P Satir; M A Sleigh; The Physiology Of Cilia And Mucociliary Interactions. Annual Review of Physiology 1989, 52, 137-155, 10.1146/annurev.physiol.52.1.137.

- Jens Elgeti; Gerhard Gompper; Emergence of metachronal waves in cilia arrays. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 4470-4475, 10.1073/pnas.1218869110.

- James R. Davenport; Bradley K. Yoder; An incredible decade for the primary cilium: a look at a once-forgotten organelle. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2005, 289, F1159-F1169, 10.1152/ajprenal.00118.2005.

- Julia C. Chen; Alesha B. Castillo; Christopher R. Jacobs; Cellular and Molecular Mechanotransduction in Bone. null 2012, na, 453-475, 10.1016/b978-0-12-415853-5.00020-0.

- João Gonçalves; And Laurence Pelletier; The Ciliary Transition Zone: Finding the Pieces and Assembling the Gate. Molecules and Cells 2017, 40, 243-253, 10.14348/molcells.2017.0054.

- Karl F. Lechtreck; IFT–Cargo Interactions and Protein Transport in Cilia. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2015, 40, 765-778, 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.09.003.

- Qicong Hu; W. James Nelson; Ciliary diffusion barrier: The gatekeeper for the primary cilium compartment. Cytoskeleton 2011, 68, 313-324, 10.1002/cm.20514.

- Jarema Malicki; Tomer Avidor-Reiss; From the cytoplasm into the cilium: Bon voyage. Organogenesis 2013, 10, 138-157, 10.4161/org.29055.

- Alison Leaf; Mark Von Zastrow; Dopamine receptors reveal an essential role of IFT-B, KIF17, and Rab23 in delivering specific receptors to primary cilia. eLife 2015, 4, na, 10.7554/eLife.06996.

- Saikat Mukhopadhyay; Hemant B. Badgandi; Sun-Hee Hwang; Bandarigoda Somatilaka; Issei S. Shimada; Kasturi Pal; Trafficking to the primary cilium membrane. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2017, 28, 233-239, 10.1091/mbc.e16-07-0505.

- Hyunho Kim; Hangxue Xu; Qin Yao; Weizhe Li; Qiong Huang; Patricia Outeda; Valeriu Cebotaru; Marco Chiaravalli; Alessandra Boletta; Klaus Piontek; et al. Ciliary membrane proteins traffic through the Golgi via a Rabep1/GGA1/Arl3-dependent mechanism. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 5482, 10.1038/ncomms6482.

- Katarzyna Szymanska; Colin A Johnson; The transition zone: an essential functional compartment of cilia. Cilia 2012, 1, 10-10, 10.1186/2046-2530-1-10.

- Björn Udo Klink; Eldar Zent; Puneet Juneja; Anne Kuhlee; Stefan Raunser; Alfred Wittinghofer; A recombinant BBSome core complex and how it interacts with ciliary cargo. eLife 2017, 6, NA, 10.7554/eLife.27434.

- Qihong Zhang; Darryl Nishimura; Tim Vogel; Jianqiang Shao; Ruth Swiderski; Terry Yin; Charles Searby; Calvin C. Carter; GunHee Kim; Kevin Bugge; et al. BBS7 is required for BBSome formation and its absence in mice results in Bardet-Biedl syndrome phenotypes and selective abnormalities in membrane protein trafficking. Journal of Cell Science 2012, 126, 2372-2380, 10.1242/jcs.111740.

- Victor L. Jensen; Stephen Carter; Anna A. W. M. Sanders; Chunmei Li; Julie Kennedy; Tiffany A. Timbers; Jerry Cai; Noemie Scheidel; Breandán N. Kennedy; Ryan D. Morin; et al. Whole-Organism Developmental Expression Profiling Identifies RAB-28 as a Novel Ciliary GTPase Associated with the BBSome and Intraflagellar Transport. PLOS Genetics 2016, 12, e1006469, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006469.

- Lin Geng; Dayne Okuhara; Zhiheng Yu; Xin Tian; Yiqiang Cai; Sekiya Shibazaki; Stefan Somlo; Polycystin-2 traffics to cilia independently of polycystin-1 by using an N-terminal RVxP motif. Journal of Cell Science 2006, 119, 1383-1395, 10.1242/jcs.02818.

- Paul P. Leyssac; Changes in single nephron renin release are mediated by tubular fluid flow rate. Kidney International 1986, 30, 332-339, 10.1038/ki.1986.189.

- Helle A Praetorius; Kenneth R Spring; The renal cell primary cilium functions as a flow sensor. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension 2003, 12, 517-520, 10.1097/00041552-200309000-00006.

- H.A. Praetorius; K.R. Spring; Bending the MDCK Cell Primary Cilium Increases Intracellular Calcium. The Journal of Membrane Biology 2001, 184, 71-79, 10.1007/s00232-001-0075-4.

- Efthimia K Basdra Christina Piperi; Polycystins and mechanotransduction: From physiology to disease. World Journal of Experimental Medicine 2014, 5, 200-205, 10.5493/wjem.v5.i4.200.

- Bradley K. Yoder; Xiaoying Hou; Lisa M. Guay-Woodford; The Polycystic Kidney Disease Proteins, Polycystin-1, Polycystin-2, Polaris, and Cystin, Are Co-Localized in Renal Cilia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2002, 13, 2508-2516, 10.1097/01.asn.0000029587.47950.25.

- Raphaël Trouillon; Biological applications of the electrochemical sensing of nitric oxide: fundamentals and recent developments. Biological Chemistry 2012, 394, 17-33, 10.1515/hsz-2012-0245.

- Guoyao Wu; Jr. Sidney M. Morris; Arginine metabolism: nitric oxide and beyond. Biochemical Journal 1998, 336, 1-17, 10.1042/bj3360001.

- Yvette C. Luiking; Mariëlle P.K.J. Engelen; Nicolaas E.P. Deutz; Regulation of nitric oxide production in health and disease. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care 2009, 13, 97-104, 10.1097/mco.0b013e328332f99d.

- U. Forstermann; W. C. Sessa; Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. European Heart Journal 2011, 33, 829-837, 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr304.

- Yong Chool Boo; Hanjoong Jo; Flow-dependent regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: role of protein kinases. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2003, 285, C499-C508, 10.1152/ajpcell.00122.2003.

- Steven Su; Siew Cheng Phua; Robert DeRose; Shuhei Chiba; Keishi Narita; Peter N Kalugin; Toshiaki Katada; Kenji Kontani; Sen Takeda; Takanari Inoue; et al. Genetically encoded calcium indicator illuminates calcium dynamics in primary cilia. Nature Methods 2013, 10, 1105-1107, 10.1038/nmeth.2647.

- Surya M. Nauli; Rajasekharreddy Pala; Steven J. Kleene; Calcium channels in primary cilia. Current Opinion in Nephrology & Hypertension 2016, 25, 452-458, 10.1097/mnh.0000000000000251.

- M. Delling; Artur Indzhykulian; X. Liu; Y. Li; T. Xie; D. P. Corey; D. E. Clapham; Primary cilia are not calcium-responsive mechanosensors. Nature 2016, 531, 656-660, 10.1038/nature17426.

- Philip M. Leonard; Sander H.J. Smits; Svetlana E. Sedelnikova; Arie B. Brinkman; Willem M. De Vos; John Van Der Oost; David W. Rice; John B. Rafferty; Crystal structure of the Lrp-like transcriptional regulator from the archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. The EMBO Journal 2001, 20, 990-997, 10.1093/emboj/20.5.990.

- Nadine Stahmann; Angela Woods; Katrin Spengler; Amanda Heslegrave; Reinhard Bauer; Siegfried Krause; Benoit Viollet; David Carling; Regine Heller; Activation of AMP-activated Protein Kinase by Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Mediates Endothelial Angiogenesis Independently of Nitric-oxide Synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 10638-10652, 10.1074/jbc.m110.108688.

- Yuanzhuo Chen; Bojie Jiang; Yugang Zhuang; Hu Peng; Weiguo Chen; Differential effects of heat shock protein 90 and serine 1179 phosphorylation on endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity and on its cofactors. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0179978-e0179978, 10.1371/journal.pone.0179978.

- Kejing Chen; Roland N. Pittman; Aleksander Popel; Nitric Oxide in the Vasculature: Where Does It Come From and Where Does It Go? A Quantitative Perspective. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2008, 10, 1185-1198, 10.1089/ars.2007.1959.

- Satoru Takahashi; Michael E. Mendelsohn; Synergistic Activation of Endothelial Nitric-oxide Synthase (eNOS) by HSP90 and Akt. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 30821-30827, 10.1074/jbc.m304471200.

- Satoru Takahashi; Michael E. Mendelsohn; Calmodulin-dependent and -independent Activation of Endothelial Nitric-oxide Synthase by Heat Shock Protein 90. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 9339-9344, 10.1074/jbc.m212651200.

- Igor B. Buchwalow; Thomas Podzuweit; Werner Böcker; Vera E. Samoilova; Sylvia Thomas; Maren Wellner; Hideo A. Baba; Horst Robenek; Jürgen Schnekenburger; Markus M. Lerch; et al. Vascular smooth muscle and nitric oxide synthase. The FASEB Journal 2002, 16, 500-508, 10.1096/fj.01-0842com.

- C.J. Lu; H. Du; J. Wu; D.A. Jansen; K.L. Jordan; N. Xu; G.C. Sieck; Q. Qian; Non-Random Distribution and Sensory Functions of Primary Cilia in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Kidney and Blood Pressure Research 2008, 31, 171-184, 10.1159/000132462.

- Linda Schneider; Christian A. Clement; Stefan C. Teilmann; Gregory J. Pazour; Else K. Hoffmann; Peter Satir; Søren T. Christensen; PDGFRαα Signaling Is Regulated through the Primary Cilium in Fibroblasts. Current Biology 2005, 15, 1861-1866, 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.012.

- Li-Wei Wu; Wei-Liang Chen; Shih-Ming Huang; James Yi-Hsin Chan; Platelet‐derived growth factor‐AA is a substantial factor in the ability of adipose‐derived stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells to enhance wound healing. The FASEB Journal 2018, 33, 2388-2395, 10.1096/fj.201800658r.

- Archana Gangopahyay; Max Oran; Eileen M. Bauer; Jeffrey W. Wertz; Suzy A. Comhair; Serpil C. Erzurum; Philip M. Bauer; Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor II Is a Novel Mediator of Endothelial Nitric-oxide Synthase Activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 33134-33140, 10.1074/jbc.m111.274100.

- Guang-Rong Wang; Yan Zhu; Perry V. Halushka; Thomas M. Lincoln; Michael E. Mendelsohn; Mechanism of platelet inhibition by nitric oxide: In vivo phosphorylation of thromboxane receptor by cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 4888-4893, 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4888.

- Xiaoping Du; A new mechanism for nitric oxide– and cGMP-mediated platelet inhibition. Blood 2007, 109, 392-393, 10.1182/blood-2006-10-053827.

- David R. Riddell; James S. Owen; Nitric Oxide and Platelet Aggregation. null 1996, 57, 25-48, 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60639-1.

- Shakila Abdul-Majeed; Surya M. Nauli; Dopamine Receptor Type 5 in the Primary Cilia Has Dual Chemo- and Mechano-Sensory Roles. Hypertension 2011, 58, 325-331, 10.1161/hypertensionaha.111.172080.

- Viralkumar S. Upadhyay; Brian S. Muntean; Sarmed H. Kathem; Jangyoun J. Hwang; Wissam A. AbouAlaiwi; Surya M. Nauli; Roles of dopamine receptor on chemosensory and mechanosensory primary cilia in renal epithelial cells. Frontiers in Physiology 2013, 5, 72, 10.3389/fphys.2014.00072.

- Aaron Marley; Mark Von Zastrow; DISC1 Regulates Primary Cilia That Display Specific Dopamine Receptors. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e10902-e10902, 10.1371/journal.pone.0010902.

- Mohammad Asghar; Seyed K. Tayebati; Mustafa F. Lokhandwala; Tahir Hussain; Potential Dopamine-1 Receptor Stimulation in Hypertension Management. Current Hypertension Reports 2011, 13, 294-302, 10.1007/s11906-011-0211-1.

- Yoshihiro Omori; Taro Chaya; Satoyo Yoshida; Shoichi Irie; Toshinori Tsujii; Takahisa Furukawa; Identification of G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) in Primary Cilia and Their Possible Involvement in Body Weight Control. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0128422, 10.1371/journal.pone.0128422.

- Gail J. Pyne-Geithman; Danielle N. Caudell; Matthew Cooper; Joseph F. Clark; Lori A. Shutter; Dopamine D2-Receptor-Mediated Increase in Vascular and Endothelial NOS Activity Ameliorates Cerebral Vasospasm After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage In Vitro. Neurocritical Care 2008, 10, 225-231, 10.1007/s12028-008-9143-2.

- Aurélien Lorthioir; Robinson Joannidès; Isabelle Rémy-Jouet; Caroline Fréguin-Bouilland; Michèle Iacob; Clothilde Roche; Christelle Monteil; Danièle Lucas; Sylvanie Renet; Marie-Pierre Audrézet; et al. Polycystin deficiency induces dopamine-reversible alterations in flow-mediated dilatation and vascular nitric oxide release in humans. Kidney International 2015, 87, 465-472, 10.1038/ki.2014.241.

- Hidemasa Goto; Akihito Inoko; Masaki Inagaki; Cell cycle progression by the repression of primary cilia formation in proliferating cells. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2013, 70, 3893-3905, 10.1007/s00018-013-1302-8.

- Yi-Ni Ke; Wan-Xi Yang; Primary cilium: an elaborate structure that blocks cell division?. Gene 2014, 547, 175-185, 10.1016/j.gene.2014.06.050.

- Olga V. Plotnikova; Erica A. Golemis; Elena N. Pugacheva; Cell Cycle–Dependent Ciliogenesis and Cancer. Cancer Research 2008, 68, 2058-2061, 10.1158/0008-5472.can-07-5838.

- Muqing Cao; Qing Zhong; Cilia in autophagy and cancer. Cilia 2015, 5, 4, 10.1186/s13630-016-0027-3.

- Jeffrey J. Talbot; Jonathan M. Shillingford; Shivakumar Vasanth; Nicholas Doerr; Sambuddho Mukherjee; Mike T. Kinter; Terry Watnick; Thomas Weimbs; Polycystin-1 regulates STAT activity by a dual mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 7985-7990, 10.1073/pnas.1103816108.

- Thomas Weimbs; Erin E. Olsan; Jeffrey J. Talbot; Regulation of STATs by polycystin-1 and their role in polycystic kidney disease. JAK-STAT 2013, 2, e23650, 10.4161/jkst.23650.

- Karen Koefoed; Iben Rønn Veland; Lotte Bang Pedersen; Lars Allan Larsen; Søren Tvorup Christensen; Cilia and coordination of signaling networks during heart development. Organogenesis 2013, 10, 108-125, 10.4161/org.27483.

- Wenguang Feng; Wei-Zhong Ying; Kristal J. Aaron; Paul W. Sanders; Transforming growth factor-β mediates endothelial dysfunction in rats during high salt intake. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2015, 309, F1018-F1025, 10.1152/ajprenal.00328.2015.