You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Operations Research & Management Science

The concept of academic spin-off (AS) has witnessed an increase in attention due to its effectiveness in solving industry problems using core technology and knowledge from academia. Most studies based on US and western Europe experiences have presented the main key factors for academic spin-offs.

- sales growth

- spin-off–university relationship

1. Introduction

Based on resource-based views, firms are acquiring capabilities and resources that are both unique and valuable. Universities play a decisive role in the development of skilled human capital [1], knowledge, and technology. Technology transfer can be undertaken through spin-offs, licensing processes, publications, and industry research and development agreements. The present paper focuses on the concept of an academic spin-off (AS), one of the most important technology transfer mechanisms in today’s changing society. The reason for this focus resides in the fact that AS companies, or university spin-offs, are one of the best ways to achieve sustainable development at a regional level and to have a real social impact [2]. Their main advantages in this line of reasoning are job creation, the diversification of businesses in a regional context, technological development, the creation of new sectors, and so on [3].

The literature discusses a variety of definitions for academic spin-offs, primarily with findings based upon case studies from the US and the UK [4,5]. Criteria used to distinguish other categories of science-based start-ups from academic spin-offs refer to the origin of the technology used, the affiliation of the founding personnel with a research institute or university, and the funding sources used that are linked to a university [6].

Smilor et al. [7] saw an academic spin-off from two perspectives: the technology transfer had to originate at a university, and at least one faculty member (active or retired) of the university had to be engaged in the establishment of the company. Following [8]’s rationale, Di Gregorio and Shane [9] explained the concept of academic spin-offs as independent companies established with the purpose of exploiting commercially patented inventions or some sort of intellectual property generated from university research.

Mathisen and Rasmussen [10] provided a more complex vision of the academic spin-off process, which saw them as active, new ventures with technology developed at public research institutions or universities [11] whose founding members were affiliated as employees of a research institution [12]. Thus, an academic spin-off (AS) can be defined as an atypical venture established by a researcher or a group (professors, scientific researchers, students, etc.) from a university or research institute that transfers a scientific result (patent application, patent, doctoral thesis, bachelor thesis, master thesis, result of a research project from a public program) to a new company in order to commercialize an innovative product or service [13].

Due to their inherent advantages for innovative commercial results, academic spin-offs are found in the literature under the following names: university spin-offs, research-based spin-offs, and spin-outs. Rogers et al. [14] showed that the highest commercialization values regarding technology transfer mechanisms were technology licensing and venture spin-out. In the same line of reasoning, Shane [5] concluded that university inventions could be successfully exploited through the formation of spin-off companies. Bray and Lee [15] demonstrated that, out of two technology transfer mechanisms, namely licensing and spin-out, the second generated ten times more income. Licensing was chosen as a process when technology was not suitable for a spin-off company. Various studies have demonstrated the clear impact of academic research on US industry [16], where academic spin-offs had better results than other start-ups [17].

According to a study from the OECD [18], between 2004 and 2010, Europe registered a higher rate of spin-off formation (2.1) than the United States and Canada (1.1), as well as Australia (0.7). However, despite their outstanding advantages and high formation rate, many spin-offs in Europe remain small, with 80% employing under ten people after six years of operation [19,20,21].

By recognizing the value of university research and AS potential for regional development, governments and policy makers have understood the need to increase the formation of new AS companies and to extend their survival rate. Thus, AS creation and their survival process has become a strategic and vital matter for national strategy. This action has caused policy makers to provide programs for spin-offs to stimulate the commercial exploitation of public research [22].

In Elpida’s [23] opinion, the supportive structures at the beginning of the academic spin-off development stage are market requirements, suitable policies and legislative conditions, and skilled human resources. In addition, it is known that urban regions develop stronger small business landscapes in comparison to other regions [24]. Thus, university cities have the potential to start AS companies in an entrepreneurial-aware marketplace.

Therefore, appropriate policies for the commercialization of the final product are necessary, together with government programs. The government must encourage universities to increase the rate of spin-offs. Achieving the right policy mix can help governments shape and strengthen the contributions that innovations provide to economic performance and social welfare [25]. In addition, the role of EU funding programs in promoting collaboration between research institutions and companies has been stressed in a variety of programs. Many of these programs have not had a solid organizational structure or clearly identified activities. Different models of academic spin-off support programs have been proposed [26].

They have provided a high level of research knowledge using public funding, but they have not managed to commercialize it for wealth creation and regional development [27].

Using data from two German regions, Sternberg [28] showed that the regional conditions in which a spin-off was formed had a bigger influence on the survival rate in contrast with the government support received from the European funds. It seems that a funding scheme did not create the same results in a different regional context [29]. Therefore, EU funding and all government programs need to adapt to the specificity of regional context. In this way, the objectives of increased AS formation and survival rate can be adequately achieved.

Vincett [30] showed in a longitudinal study on Canadian spin-off companies (1960–1998) that, in contrast with government investments, an AS had an impact on an economic level between three to four times higher. The added value an academic spin-off provides to regional development makes it an ideal candidate for future government funding programs. However, the specific survival factors for academic spin-off regional success are not fully understood. Although scholars have investigated the number of AS companies created in specific countries [31,32] and have analyzed the formation of academic spin-offs [29], few studies have looked to assess what ensures their development and survival [33,34].

Furthermore, Mathisen and Rasmussen [10] outlined the fact that studies from western Europe (most in the UK) and North America (with an emphasis in the US) are prominent in the literature. Another aspect pointed out was the problem encountered in obtaining dynamic data on AS development in eastern European countries, hindering scholars from understanding the broader European regional development context.

2. Survival Factors for AS and Performance Measurement

2.1. Main Factors Influencing the Survival of an Academic Spin-Off

There are different factors that affect the survival of a spin-off, such as entrepreneurial skills [5,11,35], characteristics of the core technology [36], industry characteristics [37,38], career experience [39], research knowledge [40], and market requirements [41].

Academic spin-offs in their early stages are influenced by the available skills from the university departments or research centers in which they are formed [42].

Following Djokovic and Souitaris’s [43] rationale, Venturini and Verbano [36] explained that an academic spin-off could achieve a bigger advantage by combining four types of resources: financial, social, technological, and human [44].

After the extensive literature review in Table 1, the connections between the four types of resources and the most important influencing factors are synthesized in Table 2.

Table 1. Summary of the factors that influence AS performance.

| Study | Country | Sample Period | Methodology | Relevant Variables | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinell et al. [11] | 60 qualitative interviews in the UK |

6-month period | Case study approach | Design and resource acquisition competence | “Successfully initiate an academic spin-off, academic founding teams must develop a specific set of entreprenerial competencies” |

| Schillo [12] | 7 spin-offs in 5 European countries | 1995–2000 | Case study approach; regression |

Organizational resources, human resources, technological resources, physical resources, financial resources, networking resources |

“Case of survival through merger or acquisition, the presence of venture capital” |

| Buenstorf [20] | 143 producers of lasers in Germany |

1964–2003 | Company longevity: over 7 years of survival; proportional Gompertz model |

Years of entry and exit from the laser industry, type(s) of lasers produced initially, mergers and acquisitions, founders’ names and backgrounds, prior employment periods, firm background prior to entry into laser industry (for diversifying firms) |

Technological capabilities are determinants of firm success |

| Clarysse et al. [26] | 43 companies employed by European research institutions | 1995–2002 | Qualitative approach | Networking resources, technological resources, financial resources |

Because the origin of each spin-out company lies within the lab, internal office space is offered for free, and infrastructure is available |

| Venturi and Verbano [36] |

2009–2012 | India | Case study approach using four stages of development by Vohora et al. (2004) |

Techn. Resources: degree of innovativeness, stage of development of technology, ability to patent and protect the technology, scope of technology; Human resources: type of parent organization (PO), founders’ positions in PO, formal team size, PhD experience or scientific background in active founding team, sector experience of at least one of the founders, management experience, previous entrepreneurial experience of team, variety of backgrounds and work experience in the team, joint working experience and cognitive similarity of the team; Financial resources: type of funding, amount of funding, social resources, relationship with PO, supporting strategy, mechanisms and financial incentives toward spin-off, tangible resources (i.e., laboratory facilities and access to research equipment), intangible resources (e.g., access to human capital, and scientific and business knowledge), scientific quality and perceived image of PO, quality and support of technology transfer office, contacts with industrial, financial, and research organizations (no. of entities), venture capital investors, financial institutions, commercial partners, competitors, customers, suppliers, or other research centers |

“…the success of RBSOs is based on technological resources, even if social resources appear to be equally important…” |

| Shane and Stuart [37] | 134 spin-offs in the USA | 1980–1994 | Event history method; regression |

Endowments: social capital (venture capital investitor); endowments: human capital (founders’ industry experience); endowments: technical assets (patents); endowments: industry attractiveness (industry conditions) |

“social capital endowments have a positive effect on the performance “, capacity to attract venture capital financing and the experience of initial public offerings influence the performance of a spin-off |

| Aspelund et al. [44] | 80 Norwegian and Swedish technology-based start-ups | 1995–2000 | Cox regression model | Team size, entrepreneurial experience, team heterogeneity, radicalness of the technology |

Team heterogeneity and radicalness of the technology increase the probability of survival |

| Soetanto and Geenhuizen [45] | 100 spin-offs in Netherlands and Norway | 2006–2008 | Curvilinear model regression |

Firm age, firm size, university-employed founder, level of innovativeness, university network density (contacts within a network connected to each other) |

“spin-off’s ability to attract external funding for innovation is influenced positively by the density of its university network” |

| Treibich et al. [46] | France and Switzerland | Too long-term periods (4–15 years); 25 case studies of spin-off |

Sharing of research equipment (parent unit: department or team) |

Biotech firms need the technical support of the parent because the cost of equipment is very high | |

| Gurdon and Samsom [47] | USA | 22 spin-offs; 1999–2000 |

Longitudinal study | Number of employees, technological knowledge, access to capital |

“Scientific expertise is essential for the long-term survival of USOs” |

| Miranda et al. [48] | Spain | 500 spin-offs; 2014 |

Squares (PLS) regression | Creativity (CREA), entrepreneurial intention of the manager, entrepreneurial attitude of the manager, perceived utility, business experience |

Academic business experience positively influences academic perceived utility, entrepreneurial attitude of the manager is the most relevant indicator for AS performance |

| De Cleyn et al. [49] | 8300 ASOs in 24 European countries | 1985–2009 | Logistic regression | Management team and director characteristics (education, work experience, heterogeneity, and participation), prior entrepreneurial experience |

“strong and positive effect of the level of legal expertise of the manager or the different effect of the previous entrepreneurial experience of the manager foster ASO survival” |

| Bolzani et al. [50] | Italy; 551 universities |

2000–2008 | GMM estimator | Parent ownership, geographical proximity, technological ties, parent board membership, entrepreneurial team, commercial experience, regional financial support, market performance, innovation skills |

Geographical proximity does not have an impact on market performance; technological ties negatively influence the market performance; parent ownership has a positive effect on market performance |

| Rasmussen et al. [42] | Norway | 12–15 months | Case study using the stages of development credibility threshold (Vohora et al., 2004) | Company founders’ entrepreneurial team member competencies, opportunity identification and development, championing resource acquisition |

University department reputation positively influences the competencies in university spin-offs |

| Bigliardi et al. [38] | Italy | 20 spin-offs | Delphi Technic | Characteristics of the university: involvement of the university by financial contribution in the company and allowing access for acquiring entrepreneurial knowledge; Characteristics of the founders: the desire to be autonomous, the motivation of the founders, and reorientation in the career; Characteristics of the external environment: characteristics of the industry, existing regional infrastructure, geographical location, and existing capital; Technological characteristics: the degree of innovation, the development stage of the product, technology or service, the ability to patent and maintain the intellectual property rights |

The performance is measured with the 4 financial factors previously identified: growth in sales, employment growth, net cash flow, and revenue growth |

Table 2. Main factors proposed that influence AS performance.

| Resource Dimensions | Factors for Spin-Off Survival | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Social resources | networking, material resources available in the incubation stage | Aspelund et al. [44] |

| Clarysse et al. [51] | ||

| quality of scientific support regarding the development of the product | Soetanto and Geenhuizen [45] | |

| the sharing of research equipment for spin-off long-term development | Treibich et al. [46]) | |

| Human resources | manager research skills | Gurdon and Samsom [47] |

| the entrepreneurial competency of the manager | Miranda et al. [48] | |

| De Cleyn et al. [49] | ||

| previous entrepreneurial experience of the team |

Rasmussen et al. [42] | |

| Hesse and Sternberg [52] | ||

| Sinell et al. [11] | ||

| the individual-level attitude towards commercialization of the research results | Würmseher [53] | |

| Hesse and Sternberg [52] | ||

| Technological resources | the stage level of the research product | Aspelund et al. [44] |

| Bigliardi et al. [38] | ||

| Venturi and Verbano [36] | ||

| Financial resources | venture capital during the growth of the firm | Schillo [12] |

| Shane and Stuart [37] | ||

| consortia of public research institutes and firms | Park et al. [54] | |

| Bolzani et al. [50] | ||

| Kroll and Liefner [55] |

The social resources group represent social ties to academia in both the incubation stage and the future development stage. It is composed of the following survival factors:

- -

-

Networking and material resources available in the incubation stage: Spin-out from research experiments where an AS receives internal office space and infrastructure for free [26]. According to Aspelund et al. [44], the initial resources in the incubation stage (human, social, and access to material equipment) were significant predictors of AS survival. From this point, the aim is to have a strong collaboration with the parent research institution [52].

- -

-

Sharing of Research Equipment for Spin-Off Long-Term Development: The knowledge infrastructure is of the greatest significance because industrial production is based on knowledge: industrial technology is knowledge related to material transformation, which is the center of the national innovation system [56]. Steffensen et al. [57] underlined that the most relevant factor influencing the success of spin-offs was the degree of support received in the growth stages.

- -

-

Quality of scientific support for the development of the product: AS companies in later stages of life focus on maintaining strong relationships with universities, aiming to increase the chance of obtaining research funding [45].

The human resources group is very complex because it envisaged the human capital necessary for AS success. Thus, it referred to the particularities of the manager, but also to team skills in different domains. The survival factors that composed this group were as follows:

- -

- -

-

The manager’s entrepreneurial competency: The available evidence on university spin-offs [58] demonstrates that, often in the initial years of functioning, the founders of the company are the managers of the AS. Since scientist-entrepreneurs do not possess commercial managerial skills [33], prior business experience has been considered an advantage for the survival of the company [42,50]. Landry et al. [59] explained how consulting experience helped in the creation of a university spin-off.

- -

- -

-

The individual-level attitude towards commercialization of the research result: The initial strategic actions taken by the employees of an AS are crucial but largely unexplored [60]. Würmseher’s [53] three entrepreneurial models explained the main challenges academic researchers face when commercializing their innovations. Inevitably, inventors who become entrepreneurs are strongly committed to technology, which is particularly useful for overcoming problems arising during the commercialization process [61].

The technological resources group take into consideration one very important survival factor, namely:

- -

-

The stage level of the research product: The level of product innovation was used as an assessment method for spin-off survival in the UK [62]. Schillo [12] considered patent protection and technological uncertainty for spin-off success. Aspelund et al. [44] showed that a higher degree of technological radicalness increased the probability of survival.

The financial resources group expressed the origin of capital and its influence on practical AS companies. The possible survival factors could be as follows:

- -

-

Consortia of public research institutes with firms: Public authorities offer grants in most cases only for the first stages of research. Thus, academic spin-offs are not able to adequately finance the next commercial development stage because they do not generate sufficient revenue to cover the needed investment costs. In this situation, scholars have outlined that parent university equity ownership is vital to the success of a spin-off [50,55].

- -

-

Venture capital during the growth of the firm: Having an idea or invention is not enough, and finance becomes critical for a spin-off company. For external source financing, we found venture capital and business angel financing. Due to the fact that an AS is a high-risk project, it loses attractiveness to banks and has to direct its efforts towards venture capitalists [63]. The performance of an AS is influenced by its capacity to attract venture capital [37].

Since there are numerous opinions in the literature and several classifications, factors determined from a resource perspective need to be statistically evaluated in terms of their influences on AS survival. Additionally, specific survival factors must be discussed for relevant results. Their importance must be compared with an appropriate performance indicator.

2.2. Measuring Academic Spin-Off Performance

Concerning the performance of an academic spin-off, scholars have different opinions. Most existing studies have presented data from successful AS companies that have overpassed the initial development phases. According to Egeln et al. [64], growth in sales, employment growth, and credit ranking were indicators for measuring AS success. Schmelter [65] expressed spin-off performance in terms of sales growth and employment growth. On the other hand, Ensley and Hmieleski [58] argued that net cash flow and revenue growth were useful indicators to measure the success of a firm.

Bigliardi et al. [38] stated that the performance of a spin-off could be measured with the help of the following indicators: growth in sales, employment growth, revenue growth, and net cash flow.

Hesse and Sternberg [51] used the number of employees to measure the growth of spin-offs. In their study, they used data from more than 10 years, demonstrating the importance of the period used to observe the development path of an AS. Schillo [12] measured spin-off performance using a multitude of indicators, such as sales growth and return, short-term and long-term profit, market share, new market outreach, and corporate liquidity.

As shown above, academic spin-off performance can be measured in several ways. The most-employed in such studies have been employment or sales growth, credit rating, and productivity indicators. Since AS companies are atypical, sales growth appears to be the best indicator for long-term survival.

2.3. Team Competency in Accessing Government Funds: A Specific Factor for Central and Eastern European Countries

Eroglu and Rashid [66] emphasized that, even if a government launches several support programs for start-up or spin-off creation, there are still several barriers that hinder their appropriate development. The support services for such entrepreneurial opportunities include innovation policies, training programs, and public funding.

Antoln-López et al. [67], in a study on 5328 firms from 29 European countries, showed how different innovation policy instruments helped new ventures overcome the liability of newness when developing new products, as well as how existing types of public instruments affected product innovation development differently. Central and eastern European countries faced similar challenges due to their cultures and emerging economies.

According to the OECD glossary [68], the following countries are part of the group of central and eastern European countries (CEECs): Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. A report from the European Commission [68] mentioned the lack of collaboration between research institutions and industry in creating innovative spin-offs and start-ups in many of these countries. In most cases, the study proved that the cooperation was developed in the context of EU funding projects (e.g., the European Structural and Investment Funds).

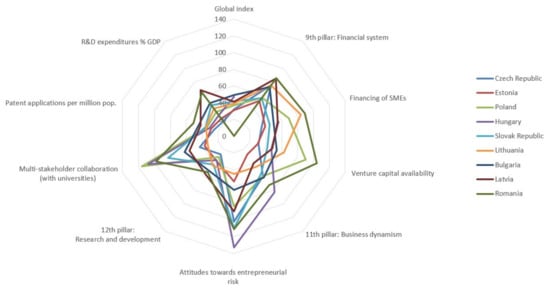

The authors adapted the data from the 2019 Global Competitiveness Report [69] by taking into consideration three main pillars that directly addressed AS formation and development: the 9th pillar of the Financial System, with its subdomains of financing SMEs and venture capital availability; the 11th pillar of Business Dynamism, with its subdomain of attitudes towards entrepreneurial risk; and the 12th pillar of Research and Development, with its subdomains of multi-stakeholder collaboration, patent applications per million population, and research and development expenditures.

The main three pillars and their selected subdomains were compared for the majority of the central and eastern European countries. In the end, Figure 1 presents the comparative ratings (ranging from 1 to 141 possible ranking places, with 1 being the best and 140 the last place in the respective domains) of these countries. It is easy to observe that they faced similar ratings and problems in the three chosen pillars. The most unsatisfactory ratings were noticed to arise in subdomains such as attitudes towards entrepreneurial risk and multi-stakeholder collaboration. It was somewhat contradictory for the good rating of the patent domain. In essence, it showed a specific cultural factor for emerging countries that was not encountered in the experiences of western societies, namely the problem in accessing EU or government funding. The problem originates from a lack of skills and experience in translating the funding program into simple rules for practical application.

Figure 1. A comparative analysis of the main central and eastern European countries based upon three AS-oriented pillars of the 2019 Global Competitiveness Report.

According to Figure 1, in 2019, as an impact of European funding, Lithuania was ranked 33rd out of 141 countries in the multi-stakeholder collaboration subdomain of the 12th pillar, followed by Estonia (37th), Czech Republic (43rd), and Latvia (56th). On the opposite side, Poland ranked 116th out of 141 countries in university–industry collaboration, followed by Hungary at 108 out of 141 countries [70], Romania (98th), and Bulgaria (62nd).

These countries have potential in the field of scientific results, as Figure 1 shows: Czech Republic was ranked 21st out of 141 countries in patent applications per million population, followed by Estonia (29th), Hungary (31st), Poland (34th), and Lithuania (35th). Romania was ranked 51st out of 141 countries in patent applications per million population.

There are national financial schemes from the European Union that target certain stages of the spin-off process. The accession of European funds for establishing academic spin-offs requires effort in elaborating complex budgetary proposals, meeting public economic needs, and respecting strict rules regarding costs. In this complex mechanism, new companies suffer from a lack of skilled and experienced labor force. Additionally, they are less likely to have acquired the suitable practices to succeed in the project requirements, to respect the conditions of submitting a project, and to know how to communicate with representatives of European funds, that are specifically developed in completing these actions. Because new ventures do not fully understand the conditions of submitting projects for grants, wrong decisions are made that can influence the longer survival of an AS.

In Hungary, the 2017 RIO Country Report [71] showed that university–industry collaboration centers and continued investment in research and development led to improvement in the 2017 Global Innovation Index.

In Lithuania, the 2017 RIO Country Report [72] mentioned that the period of 2014–2020 had a greater impact and influence on the development of technology transfer centers and the stimulation of AS formation compared to the period of 2000–2015, when structural funds (ESIF Research and Development and Innovation projects) did not encourage sustainable forms of collaboration between universities, industry, and business.

In the Czech Republic, a major weakness is represented by the collaboration between research and industry [69]. In the 2017 RIO Country Report [73], it was underlined that measures were taken to face the problem by the establishment of national centers of competence with the aim of strengthening the relationship between the public and private spheres. The result was objectively achieved because, in 2019, the Czech Republic ranked 108th out of 141 countries in the multi-stakeholder collaboration subdomain of the 12th pillar. The indicator of the National RIS3 Strategy 2021+ referred to spin-offs generated with a turnover of EUR 1 million after five years of operation. The Czech Republic Innovation Strategy 2019–2030 pointed out that the number of AS companies should increase by using EU funds and national resources.

In recent years, in Poland, the government has made efforts to establish the right conditions to encourage university entrepreneurs. Being a late entrant in the research and development competition, the number of academic spin-offs has increased in the context of public funding from the UE [74]. According to the 2019 Global Competitiveness Report, Poland ranked 116th out of 141 countries in university–industry collaboration, even though the number of patents offered Poland the 29th position. Since 2014, it appears that public funding, such as NCBR’s Bridge Alfa program and Biznest, designed to help develop AS companies and start-ups has had an impact at the regional and national levels [75]. In addition, Korpysa [76] showed in a study on Poland spin-offs that the codification of legislation for business opportunity, seen as an exogenous factor, influenced the development of these atypical companies. Even if in the national context there were available funds for the development of AS, entrepreneurs were sceptical.

A report from [69] noted that, in Slovakia, there was a lack of skilled labor force in universities. Since universities encounter problems because of bureaucracy, it is more likely that, in Slovakia more than elsewhere in Europe, research institutes do not have any knowledge about opportunities concerning the development of academic spin-offs. Although Slovakia registered good values regarding patents (36th position) and research and development expenditure percentage (46th position), when it came to university and industry collaboration it was ranked 83rd.

In Romania, academic spin-offs were seen as companies recently created or in their formation stage that emerged because of a university or research center research and development project. The national program for the “Development of Technological Transfer & Infrastructure—INFRATECH” (approved by GD no. 128/2004) provided financial and logistical support for the establishment and development of specialized technological transfer (TT) institutions, such as TT centers, technology incubators, and science parks, because the scientific support received from academia in the development of the product was considered very important.

The main objective of the Sectorial Growth of Economic Competitiveness Operational Program (POSCCE) for the period of 2007–2013 was the establishment of innovative spin-offs that created economic benefits. The absorption rate was EUR 2,179,933,761 (85.94%), and the number of patent applications submitted by research institutes increased six times more compared to 2001.

The Global Competitiveness Report for 2014–2015 showed that a problem in business was bureaucracy and access to funding. The new Competitiveness Operational Program of 2014–2020 allocated EUR 1582.77 million to stimulate start-up and spin-off innovation enterprises.

In the entrepreneurial finance literature, it has been pointed out that AS companies are very risky, and those with clear opportunities for growth encounter obstacles in obtaining funds for developing their innovative services or products [5,22,27]. Soetano and Geenhuizen [45] showed that sustainable businesses had labor forces with the ability to attract funding for innovation activities.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14148328

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!