Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Community-based tourism (CBT) is conceived as a form of relatively low-scale tourism that is managed by a group of locally owned businesses to benefit the community and, in some cases, contribute to conservation (when taking place in or near protected areas) . It is marketed as a means of enhancing livelihoods and creating opportunities for community development and is defined as being in, owned, and managed by the community, which receives a sizable portion of the benefits.

- community-based tourism

- sustainable tourism perception

- structural equation modelling

- semantic network analysis

- mixed methods

- central Asian countries

1. Community-Based Tourism

Community-based tourism (CBT) is founded on the notion of sustainable development since it encourages community engagement in order to achieve more equitable and comprehensive development [1] By focusing on local (rural, native, etc.) cultures, CBT assures that communities do not diminish and perish and that communities may be seen strategically as a means of enhancing the resilience of social and ecological systems, thereby contributing to sustainable development [2]. Residents of traditional villages have resurrected local customs and culture and showcased them to visitors [3][4]. As a result, CBT is observed to be critical for poverty reduction since it fosters community development, therefore working toward community sustainability.

However, tourism may have negative consequences, including an increase in the cost of living [5], unequal distribution of tourism revenue [6], low-skilled and low-paying employment [7], degradation of natural and cultural resources [8], crime and crowded living areas [6][9], and a low level of empowerment [10]. These adverse effects may have a detrimental effect on local inhabitants, as well as the economy, culture, and environment, impeding further sustainable CBT. Despite this, many emerging destinations have seen an opportunity in CBT development as an efficient way to reduce poverty and raise the awareness of the destination, heritage, culture, and traditions. This trend is causing economic pressure on some villages, which in turn is forcing young people to move to urban areas. Nevertheless, there is still a strong segment of the urban population that is interested in visiting rural areas and understanding the way of life [11].

Regardless of all the debates on applications of CBT concepts and sustainable tourism practices, there is very little evidence of an understanding of perceptions of current and pre-CBT development destinations and the effects of tourism development on tourists’ perceptions and decisions [12]. Additional analysis of community-based tourism sustainability perception is needed that provides insight on how to manage and monitor changes caused by tourism development in emerging regions and evaluate the perceived value that CBT activities actually carry for tourists.

2. Tourists’ Perceptions of CBT

Central to the understanding of tourism as a phenomenon has always been the question of the reasons that determine why people travel to certain destinations [13]. The answer to this question becomes vital for tourist destinations since, in the struggle for attracting tourists, they have to make a significant promotional effort to be noticed and chosen. Regional or national cultural distinctions are significant tourist drivers [14].

People desire to learn about different native cultures and to introduce their own to the locals. Tourists’ views of tourism products and places are critical for destination development, management, and promotion, as several destination image studies have demonstrated [15]. The significance of knowing how tourists receive and generate destination image perceptions is that these features play a significant influence in visitors’ destination decision-making processes. In other words, because visitors do not experience a location prior to deciding to visit and making reservations, their consuming decisions are influenced by what they believe in and the thoughts and feelings they identify with it [16]. This is especially true when other process variables—for example, prices, proximity across areas, views, expertise, technology, and trust—are comparable amongst accessible options [17].

Given the critical role of perceptions on destination image formation and tourist consumption dynamics, the concept of destination competitiveness emphasizes that a destination’s success is contingent on its capacity to deliver experiences that surpass visitors’ expectations [18]. However, expectations are influenced by travellers’ views of places [19]. Therefore, destination management must know how tourists perceive their locations in order to surpass their expectations. Sustainable tourism behaviour is the focus of many researchers. The studies conducted by Grilli et al. [20], Nok et al. [21], Mathew and Sreejesh [22] claim that the understanding of sustainability, shown by the tourists, is connected with their preferences in sustainable travelling practices. The perceptions of sustainability become crucial in the moment of destination selection and evaluation of tourism activity impact on the local community. In addition, such factors as the quality of existing sustainable initiatives and encouragement of sustainable practices are considered to be important in the evaluation of the sustainable component of CBT practices [23].

Similarly, understanding tourists’ expectations and impressions of a location are critical for tourism planning, as they influence tourists’ choices and consumption decisions [17].

3. Tourists’ Sustainability Preferences and Community Involvement

It is known that to produce economic and social advantages for local communities, tourism firms’ value proposition should be able to attract tourists that have preferences for sustainable practices and do become involved respectfully with the communities’ activities and social environments [24]. That is, consumer preferences for the external environment and infrastructural facilities within a tourism location can have an impact on the success of sustainable tourism.

Following CBT as a sustainable tourism derivative, it needs numerous stakeholders to collaborate and develop partnerships, pooling their talent, resources, and knowledge [25]. It enables tourists to connect with indigenous communities in a quiet and natural setting, learn about traditional ways of life, and enhances the dynamic and intriguing relationship between customers and the community [26].

CBT places a premium on human engagement and helps visitors through the process of interaction to gain a better understanding of their communities’ culture and history [27]. As a result, researchers should examine the total reaction of tourists in a continuous process using CBT as a starting point. Nevertheless, little research has explored how the level of perceived community engagement in CBT, and the advantages created for them, affects the choices made by tourists when visiting developing destinations [28].

Only a few studies that have examined customers’ preferences for attributes related to local communities have found some evidence, demonstrating impartial or even critical attitudes toward community involvement [29], while others exemplify stronger preferences for local community involvement or benefits [30][31][32].

Rihova et al. [33] claim that tourism is a collaborative and shared experience and that outcomes are achieved via interaction. Therefore, additional insight is needed to comprehend both tourists’ preferences and the ability of locals to provide services, and engage and share their communities with visitors. This is especially true in locations with a history of civil strife and in areas where tourists and inhabitants come from diverse social and cultural backgrounds [34][35].

Individual behaviour, which within a group gives rise to collective behaviour that identifies and characterizes the culture in question, is governed by the conviction or belief of each individual regarding the correct form of behaviour in each situation. This echoes the approach to the definition of values tourists and organizations in the sector have and share [36]. The values play an important regulatory role in human activity and therefore in attitudes toward the surrounding world, which establishes a correspondence between what is thought, what is said, and what is done, at the individual level [37]. The values play a key role in the model of sustainability empathy [38] that tries to unite all the influencing matters together and adds the psychological dimension. It uses the tourists’ values as a key factor that can determine their attitude toward the local community and sustainable practices.

4. Community-Based Tourism in Central Asia

Central Asian countries have been included in the “bucket list” of the tourists [39] that experience tensions from time to time and pose some “roadblocks” that cause concerns to travel. However, the introduction of e-visa types in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan has significantly increased the flow of visitors and made them more attractive for inclusion in the Lonely Planet’s pick list of destinations in 2018–2019. Nevertheless, the key issues are not just border-crossing difficulties and neighbourhood drama, but also the need for adequate sustainability policies and practices, and legislation mechanisms that preserve natural resources and reduce the negative impact of the industry and boost the local economy.

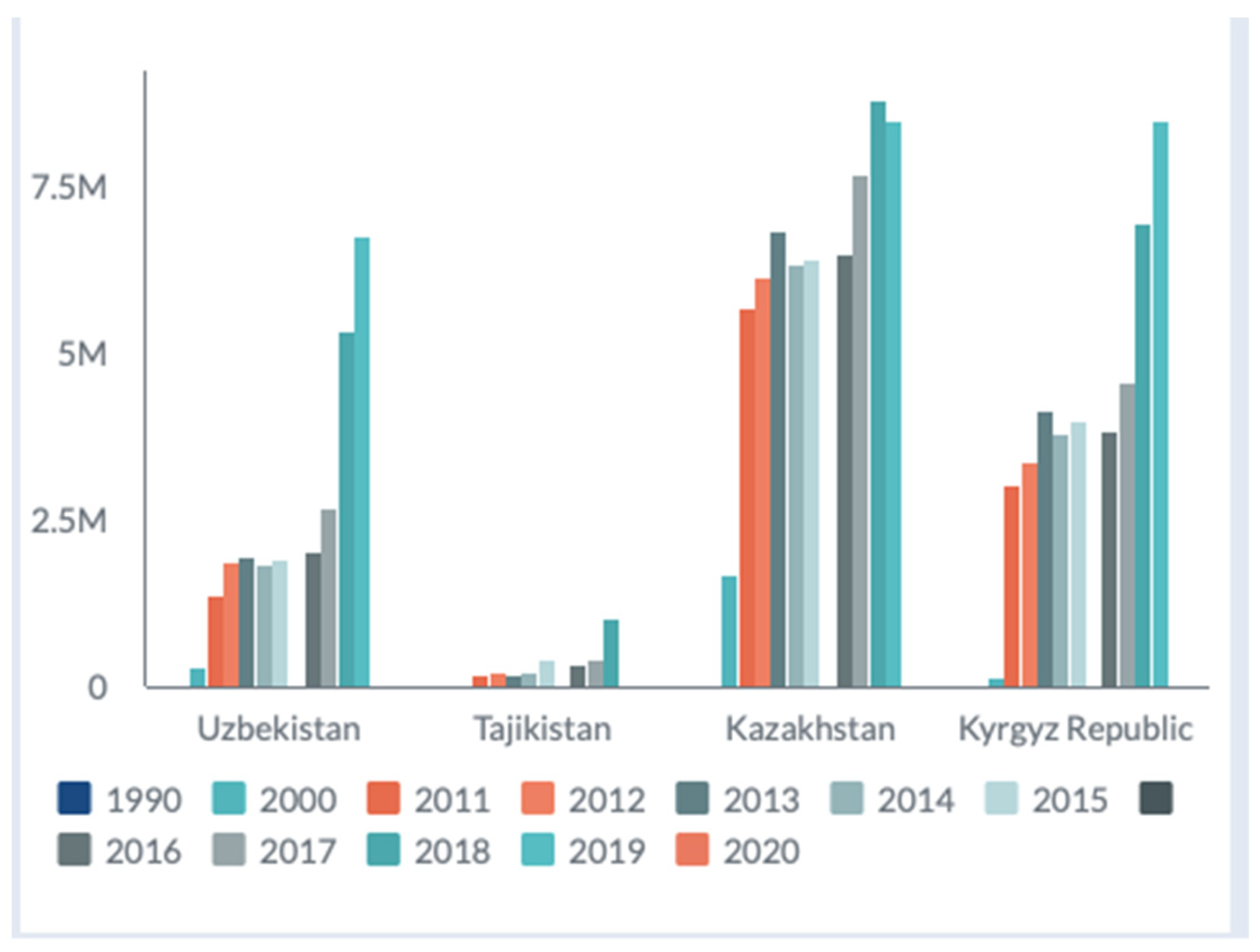

As shown in Figure 1, Central Asian countries were visited by over 15.5 million tourists in 2018 [40], led by Kazakhstan (over 8.7 million) and Uzbekistan (over 5.3 million). The first CBT group opened its doors during May 2000 in Kochkor village in Kyrgyzstan offering tourists cultural and authentic experiences and providing direct incomes for rural families. CBT enterprises in the region offer independent tourists and tour operators accommodation services for homestays, stays at authentic traditional yurts/jailoo, trekking on horses, local guide tours of heritage sites, demonstrations of handicraft skills, etc. Individual service providers directly benefit from sales, and CBT suppliers charge a rate for each service sold (up to 15%).

Figure 1. International tourist arrivals in Central Asia (The World Bank, 2020).

Uzbekistan is showing intensive development of tourism and tourist services in recent years, with growing niches involving ecotourism, agrotourism, archaeological and ethnographic tourism, and extreme tourism, all related to CBT. In the Jizzakh region, such as the Forish area and Zaamin National Park, special attention is being given to creating infrastructure for CBT activities. Family guesthouses and homestays are gaining popularity among families as their first choice of entry to the tourism business in regions such as Bukhara, Samarkand, Surkhandarya, Khorezm, Fergana Valley, and Tashkent.

Kazakhstan’s sustainable and competent activities of CBT have contributed to improving the living standards of the rural population, reducing unemployment, and increasing the welfare of the society in the regions.

Kyrgyzstan launched its first CBT project in partnership with the Swiss Association for International Cooperation Helvetas, which since 2003 has been under the umbrella of the Kyrgyz Community-Based Tourism Association (KCBTA). More than 1400 units are currently involved in CBT in the country. CBT is operating in several villages in Kochkor, Naryn, and Tamchi, where CBT aims at the progress of tourism under the supervision of residents. Participants in CBT projects can be rural residents, local nongovernmental organisations, and the local administration, and the selection criterion is based only on the ambition and opportunity to engage in tourist activities.

The Canadian Adventure Travel Company (social enterprise) “G Adventures” has been involved in the promotion of CBT tourism in Central Asia since 2016 starting in Kyrgyzstan. In addition, the nonprofit organisation “Planeterra Foundation” established the its first Central Asian project (more than 100 projects worldwide) in Kyrgyzstan—Barskoon village. Project “Ak Orgo” (White Yurt) supports local craftsmen workshop of yurt making that helps to sustain the technique of authentic yurt building skills, passing the knowledge to the younger generations by directly hiring and involving youth at the workshop, with ten people directly hired and over 1000 community members benefited [41].

Tajikistan received 1.3 million international tourists between January and December 2019 [40]. Various organizations such as META (Murgab Ecotourism Association), PECTA (Pamir Eco-Cultural Tourism Association), ZTDA (Zerafshan Tourism Development Association), MSDSP (Mountain Societies Development and Support Project), and the Ecotourism Resource Information Centres, have led the promotion of responsible travelling by implementing community development projects, training programs in business management, language learning programs, support homestays, and assistance with necessary infrastructure.

Turkmenistan is a highly isolated country with hard travelling restrictions only comparable with North Korea. There are complicated visa processes and regulations that make access to the country only possible by invitation from an individual or agency. The latest available data on the number of tourists visiting Turkmenistan refers to 2007 [41], counting 8200 visitors. However, the country’s authorities have announced a new policy intended to raise the number of tourists and develop tourism infrastructure. The attraction of the Darvaza gas crater (or Gates of Hell) has become very popular among adventure and dark tourists. Despite the difficulty of establishing CBT practices and venture activities, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in partnership with the Kyrgyz CBT Association is providing community training for guest houses or homestays in Turkmenistan [39].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14137540

References

- Stone, M.T.; Stone, L.S. Challenges of community-based tourism in Botswana: A review of literature. Trans. R. Soc. S. Afr. 2020, 75, 181–193.

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E. Social-ecological resilience and community-based tourism: An approach from Agua Blanca, Ecuador. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 655–666.

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468.

- Wearing, S.L.; Wearing, M.; McDonald, M. Understanding local power and interactional processes in sustainable tourism: Exploring village–tour operator relations on the Kokoda Track, Papua New Guinea. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 61–76.

- Lee, C.K.; Back, K.J. Examining structural relationships among perceived impact, benefit, and support for casino development based on 4 year longitudinal data. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 466–480.

- Alam, M.S.; Paramati, S.R. The impact of tourism on income inequality in developing economies: Does Kuznets curve hypothesis exist? Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 111–126.

- Davidson, L.; Sahli, M. Foreign direct investment in tourism, poverty alleviation, and sustainable development: A review of the Gambian hotel sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 167–187.

- Bowers, J. Developing sustainable tourism through Eco museology: A case study in the Rupununi region of Guyana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 758–782.

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690.

- Hatipoglu, B.; Alvarez, M.D.; Ertuna, B. Barriers to stakeholder involvement in the planning of sustainable tourism: The case of the Thrace region in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 306–317.

- Zapata, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Lindo, P.; Vanderschaeghe, M. Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 725–749.

- Lee, T.H. A structural model for examining how destination image and interpretation services affect future visitation behavior: A case study of Taiwan’s Taomi eco-village. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 727–745.

- Agapito, D.; Pinto, P.; Mendes, J. Tourists’ memories, sensory impressions and loyalty: In loco and post-visit study in Southwest Portugal. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 108–118.

- Sosa, M.; Aulet, S.; Mundet, L. Community-based tourism through food: A proposal of sustainable tourism indicators for isolated and rural destinations in mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6693.

- Tavares, J.; Tran, X.; Pennington-Grey, L. Destination images of the ten most visited countries for potential Brazilian tourists. Tour. Manag. 2020, 16, 43–50.

- Paunovic, I.; Jovanovic, V. Sustainable mountain tourism in word and deed: A comparative analysis in the macro regions of the Alps and the Dinarides. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2019, 59.

- Buhalis, D. The tourism phenomenon: The new tourist and consumer. In Tourism in the Age of Globalisation; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2005; pp. 83–110.

- Papatheodorou, A. Why people travel to different places. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 164–179.

- Lima Santos, L.; Cardoso, L.; Araújo-Vila, N.; Fraiz-Brea, J. Sustainability perceptions in tourism and hospitality: A mixed-method bibliometric approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8852.

- Grilli, G.; Tyllianakis, E.; Luisetti, T.; Ferrini, S.; Turner, R.K. Prospective tourist preferences for sustainable tourism development in Small Island Developing States. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104178.

- Nok, L.C.; Suntikul, W.; Agyeiwaah, E.; Tolkach, D. Backpackers in Hong Kong–motivations, preferences and contribution to sustainable tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 1058–1070.

- Mathew, P.V.; Sreejesh, S. Impact of responsible tourism on destination sustainability and quality of life of community in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 83–89.

- Budeanu, A. Sustainable tourist behaviour–a discussion of opportunities for change. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 499–508.

- Jetter, L.; Chen, R. Destination branding and images: Perceptions and practices from tourism industry professionals. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 174–187.

- Ozturk, A.B.; Qu, H. The impact of destination images on tourists’ perceived value, expectations, and loyalty. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 9, 275–297.

- Liu, C.H.; Jiang, J.F.; Gan, B. The antecedent and consequence behaviour of sustainable tourism: Integrating the concepts of marketing strategy and destination image. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 829–848.

- Jarvis, N.; Weeden, C.; Simcock, N. The benefits and challenges of sustainable tourism certification: A case study of the Green Tourism Business Scheme in the West of England. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2010, 17, 83–93.

- Tolkach, D.; King, B. Strengthening community-based tourism in a new resource-based island nation: Why and how? Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 386–398.

- Capriello, A.; Altinay, L.; Monti, A. Exploring resource procurement for community-based event organization in social enterprises: Evidence from Piedmont, Italy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2319–2322.

- Okazaki, E. A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 511–529.

- Dikgang, J.; Muchapondwa, E. The economic valuation of nature-based tourism in the South African Kgalagadi area and implications for the Khomani San ‘bushmen’community. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2017, 3, 306–322.

- Carballo, M.M.; Araña, J.E.; León, C.J.; Moreno-Gil, S. Economic valuation of tourism destination image. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 741–759.

- Rihova, I.; Buhalis, D.; Moital, M.; Gouthro, M.B. Conceptualizing customer-to-customer value co-creation in tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 356–363.

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633.

- NatGeo. 2018. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/projects/out-of-eden-walk/media/2018-02-on-foot-in-the-path-of-the-silk-road/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Kruczek, Z.; Szromek, A.R. The identification of values in business models of tourism enterprises in the context of the phenomenon of overtourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1457.

- Kim, M. A systematic literature review of the personal value orientation construct in hospitality and tourism literature. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102572.

- Adongo, C.A.; Taale, F.; Adam, I. Tourists’ values and empathic attitude toward sustainable development in tourism. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 251–263.

- OSCE. 2009. Available online: https://www.osce.org/bishkek/63428 (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- The World Bank. 2020. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?locations=KZ-UZ-KG-TJ&most_recent_year_desc=false (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- World Bank. Central Asia; Tourism a Driver or Development. 2017. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/10/31/central-asia-tourism-a-driver-for-development (accessed on 5 January 2021).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!