Caffeine is a natural trimethyl xanthine alkaloid in which the three methyl groups are located at positions 1, 3, and 7 (1,3,7-Trimethylxanthine). Caffeine has high oral bioavailability, with 99% of caffeine being absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract into the bloodstream 45 min after ingestion. A peak plasma concentration of 1–10 μM (0.25–2 mg/L) reached 15–120 min post oral ingestion from a cup of coffee in humans. Caffeine, a key psychoactive ingredient in coffee, is a short-acting neurostimulator with known neuromodulator effects on the brain by inhibiting phosphodiesterase, mobilizing intracellular calcium, antagonism of adenosine receptors, and modulation of GABA receptor function. Rodent studies have also reported caffeine can inhibit amylogenic-Aβ protein production and improve cognition in rodent AD models. However, results from previous clinical studies were controversial, with some reporting caffeine to be neuroprotective, while others report no effect or even detrimental effects on cognition. Therefore, this study reviewed the existing literature and found that clinical studies propose that caffeine is neuroprotective against dementia and possibly AD.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is reported to be the leading cause of dementia and the significant healthcare burden of the 21st century [

1]. In 2015, over 46 million people were reported to be living with dementia (costing US 818 billion), a figure projected to reach 131.5 million dementia patients by the year 2050 [

2]. Developed countries with an ageing population are expected to be worse hit by this burden. Typical clinical presentation of dementia includes memory impairment and executive function decline that interferes with daily activities making the elderly less independent and forcing them to engage with support services [

1]. Atypical presentation of dementia consists of a more pronounced memory deficit causing language, visual, and executive problems [

1]. Atypical dementia is more common in early-onset dementia, which is reported to have a strong genetic component [

1].

The pathophysiology of AD is based on the accumulation of abnormally folded

Aβ and Tau proteins in amyloid plaques and neuronal tangles that contribute to neurodegeneration in patients’ brains [

3]. Much of this evidence comes from studying familial AD, where there exist mutations in APP genes, which alter the action of

γ-secretases that cleaves Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), causing an accumulation and aggregation of

Aβ peptide [

4]. Hyperphosphorylated Tau (PTau) protein, another prerequisite for AD diagnosis, accumulates intracellularly and fibrillates into paired helical filaments that form neurofibrillary tangles [

5]. It has been proposed that PTau can further accelerate

Aβ dysfunction [

5]. A significant genetic factor for AD is APOE mutations, with the lifetime risk of AD being 50% for homozygous APOE4 carriers and 20–30% for APOE3 and APOE4 heterozygous carriers [

6]. However, even without an APOE mutation at 85 yr of age, there is an 11–15% risk of developing AD, indicating there might be a significant environmental component to AD [

6]. Recent evidence has suggested many lifestyle factors: diabetes, diet, socioeconomic status (SES), education, physical and mental activity, depression, tobacco use, and alcohol intake may affect the chance of developing AD and dementia [

7]. The Rotterdam study even demonstrated that eliminating the seven most hazardous risk factors could reduce the incidence of dementia by 30% [

8]. In the absence of a definitive clinical treatment currently, eliminating these modifiable risk factors is our best tool for reducing the burden of dementia and AD.

Coffee, the most heavily consumed caffeinated beverage, has been a popular research topic in AD, with several epidemiological studies positing its neuroprotective effect [

9]. Coffee comprises a few independently neuroprotective components: caffeine, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and trigonelline [

10]. Chlorogenic acid has been shown to reduce blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage and improve neuronal differentiation in mice [

11]. Caffeic acid and phytochemicals in coffee act as antioxidative and anti-inflammatory substances, thereby helping reduce cognitive decline [

12]. Trigonelline from coffee beans has been shown to alleviate neuronal loss by reducing oxidative stress, astrocyte activity, and neuroinflammation while preserving mitochondrial integrity [

13]. The neuroprotective properties of coffee have been heavily linked to its high caffeine content, but this has been difficult to demonstrate independently through epidemiological studies due to the confounding effect of other components in caffeinated beverages [

9].

2. Effect of Coffee/Caffeine

Studies by Haller et al. [25,38] showed in early cognitive decline, there is an increase in compensatory basal activity diffused through the posto-temporal region of the brain, which increases the brain’s sensitivity to the neuroprotective action of caffeine [25,38]. Furthermore, MRI studies by Ritchie et al. [35] and Haller et al. [26] showed that caffeine reduces the amount of white matter lesion/cranial volume in cognitively stable elders, contributing to cognitive decline in Dementia/AD [26,43]. Ritchie et al. [43] also showed increased cerebral perfusion in chronic coffee consumers, indicating a possible neuroprotective mechanism of coffee [43]. Moreover, Gelber et al. [39] found high caffeine levels were associated with a lower-odds of having any brain lesion types at autopsy [39]. However, an epidemiological study by Kim et al. [31] did not find any association between coffee intake and hypometabolism, atrophy of AD signature, and WMH volume; instead, it found that coffee exerted a neuroprotective effect by reducing the levels of Aβ [31].

Current literature also seems to support the notion that caffeine/coffee acts as a cognitive normalizer instead of a cognitive enhancer, and as such healthy adults or those with deteriorating cognition receive little benefit from coffee/caffeine treatment [

25,

26,

33,

38]. West et al., found that elderly participants with mild cognitive decline showed higher sensitivity to caffeine than healthy younger diabetics [

33]. Furthermore, Haller et al., found no changes in neural activation among healthy adults but increased posto-temporal activation in those with MCI, further supporting the notion that caffeine does not act as a cognitive enhancer [

38]. Other than that, caffeine/coffee cannot significantly enhance the cognitive function of those suffering from severe cognitive decline [

25,

26]. Haller et al., showed that caffeine reduces the amount of white matter lesion/cranial volume and increases cerebral perfusion in cognitively stable elders but did not extend the same benefits to elders with deteriorating cognition [

26]. Furthermore, Haler et al., in another study used fMRI to study the neural activation induced by caffeine for participants with deteriorating cognition; although this study showed that caffeine reduced cognitive decline in dCON, it did not show the same level of caffeine-induced neural activation in them as seen in those with sCON [

25].

The literature also shows that the neuroprotective effect of caffeine/coffee can be confounded by gender, but the evidence is not definitive for either gender, and further research is needed [

24,

28,

34,

43]. Two studies (Ritchie et al. [

28,

43]) only found a statistically significant neuroprotective effect of caffeine among women in the study population but not males [

28,

43]. Furthermore, Sugiyama et al. [

24] found an overall neuroprotective effect of coffee, but this was enhanced among the female cohort and non-smokers and non-drinkers [

24]. However, Iranpour et al., in a crude model, found the neuroprotective effect of caffeine extended to both genders, but after adjusting for confounding, found a weak positive correlation for the neuroprotective effect of caffeine only among the males only [

34]. The exact mechanism for the difference in neuroprotective properties of caffeine/coffee between gender is unclear and warrants further research; however, it has been hypothesized that this may be due to differences in caffeine metabolism, pharmacodynamics, or hormonal influence [

28,

34].

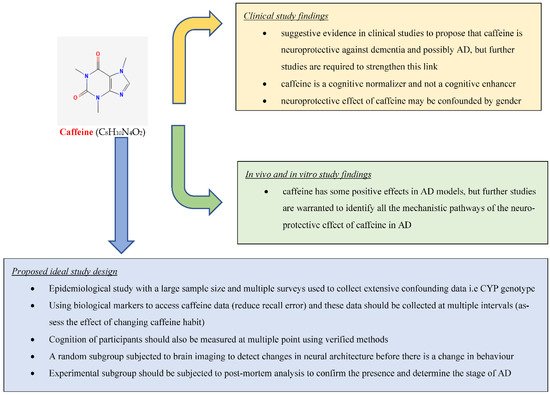

Although there is evidence from the clinical studies suggesting that caffeine consumption is protective against AD cognitive decline, further clinical studies are required to prove this link. Ideally, to examine this link, there would need to be an epidemiological study with a large sample size, with multiple surveys collecting extensive data on confounding variables to be adjusted, including data on CYP genotype. The study should also use biological markers (blood tests) to assess caffeine to reduce recall bias, and caffeine data should be collected at multiple points (incl: midlife) during extended follow-up to assess changes in behavior. Furthermore, cognition should also be measured using verified methods, i.e., MMSE, CDR, CERAD, during follow-up. A sub-group should also be randomly chosen and subjected to brain imaging at set intervals during follow-up to identify changes in neural architecture before shifting in behavior. This subgroup should also be subjected to post-mortem analysis to confirm the presence and stage of AD (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summary of findings.

This review also analyzed in vivo and in vitro studies that directly examined the relationship between caffeine on AD and cognition, which shows strong evidence that caffeine is neuroprotective against AD through multiple mechanisms. These studies also suggest possible mechanisms of caffeine’s neuroprotective effect. Four of these studies show that caffeine alters APP processing to a non-amyloid pathway, reducing AD burden and cognitive decline [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Furthermore, five of these studies show that caffeine‘s neuroprotective effect is due to its ability as a non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. Other than that, studies have also shown that caffeine’s neuroprotective effect is due to its ability to alter protein aggregation [

55,

56]. We also found evidence that caffeine is able to reduce BNDF levels [

58,

59]. Caffeine also reduces acetylcholinesterase activity, a mechanism for its neuroprotective effect against AD [

66,

67]. Some studies showed that the neuroprotective effect of caffeine is by: affecting membrane properties [

49], changing GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission [

54], reducing endolysosome dysfunction [

65], increasing GCSF function [

68], and increasing

Aβ clearance [

69].

Through this review, we also identified a few in vivo and in vitro studies that were excluded because they did not directly examine the relationship between caffeine and AD. These, however, also posited possible mechanisms of action for the neuroprotective effect of caffeine. Reznikov et al., showed that caffeine significantly enhanced C-Fos expression in the horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca [

80]. This is thought to explain why AD patients lose their olfactory sense first and that the cognitive enhancing effect of caffeine may be through activation of the basal cholinergic forebrain [

80]. Furthermore, Vila-luna et al., showed that the caffeinated group of mice had greater fourth and fifth-order basal dendrites branching in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Laurent et al. showed caffeine’s ability through A2R antagonism/knock out for normalization of hippocampal GSH/GSSG ratio, global reduction in Tau hyperphosphorylation, and neuroinflammatory markers [

81].

3. Conclusion

This review found suggestive evidence in clinical studies to propose that caffeine is neuroprotective against dementia and possibly AD, but further studies are required to strengthen this link (Figure 1). The review also found strong evidence based on in vivo and in vitro studies that caffeine has some positive effects in AD models, but further studies are warranted to identify all the mechanistic pathways of the neuroprotective effect of caffeine in AD.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules27123737