1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Numerous studies show the profound impacts of climate change on Indigenous peoples across different countries [

1,

2,

3]. These impacts have negative consequences for Indigenous communities, who are often poor and rely heavily on natural resources to sustain their livelihoods [

4,

5]. The extent of the impact of shocks and stresses at the community level depends on the intensity of climate hazards combined with the vulnerability and the capacity of those affected to cope with them [

6,

7]. Indigenous communities experience different levels of impact based on their livelihoods [

4,

8,

9]. Rising temperature averages increase farmers’ irrigation costs and reduce hunters’ potential hunt, while extreme waves and wind reduce fishermen’s working days [

4]. In the tourism industry, storms, droughts, and floods adversely affect tourism destination areas [

10]. These hazards cause damage to infrastructure and built assets while discouraging tourist arrivals because of risk perceptions of the regions as unsafe, thus causing significant economic loss [

11]. These studies show that Indigenous peoples experience various impacts on their livelihood routines and may resort to different coping strategies to alleviate these impacts [

12]. However, there is not much understanding of how multiple climate change impacts affect Indigenous economic activities, such as loss of natural resources and reduced tourism income, and influence Indigenous persons’ attitudes, support, and participation in climate adaptation.

Indigenous peoples’ perceptions of climate change and adaptive capacity can be influenced by multiple factors [

21,

27]. Climate hazards such as sea-level rise, drought, and floods can influence Indigenous peoples’ perceptions and undermine their capacity to cope with climate impacts [

1,

25]. Other research indicates that non-climate variables such as sociocultural factors (e.g., age, education, and income), socio-political, and livelihoods can also alter Indigenous peoples’ perceptions and increase their vulnerability [

8,

28]. As a result, focusing just on climate hazards may limit the understanding of how numerous components interact and affect Indigenous peoples’ perspectives [

18,

21,

27]. Due to the intricate interplay between many elements, changes in time, and context, measuring or ranking the most important factors impacting Indigenous communities’ attitudes remains a challenge [

27]. In this view, the current study employs partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), an advanced multivariate method of statistical analysis that is useful for assessing the relationships between multiple factors simultaneously, hence identifying the key predictor of Indigenous peoples’ perceptions of climate impacts [

29,

30].

2. The Context of a Study

Out of thirteen states, Sabah (73,000 km

2) is the second largest state in Malaysia. The Kinabatangan district is located in East Sabah, under the administration of the Sandakan division. Kinabatangan River is the largest and longest river in Sabah. It has a length of 560 km and a catchment area of 16,800 km

2 and covers almost 23% of the total land area of Sabah. The river is one meter above sea level, but it can rise as high as 12 m above sea level during heavy rain. Most Kinabatangan villages are located in the lowlands along the river. Historically, the Kinabatangan area is dominated by natives known as Orang Sungai (River people) [

36]. The majority of the Sungai people are Muslim, and they live in scattered settlements along the Kinabatangan River. The Sungai people have always lived along the Kinabatangan River to barter (a traditional exchange) forest products with traders who sail on this river [

36,

37]. The Sungai people engage in subsistence farming, fishing, seasonal fruit harvest, collection, and the sale of forest harvest [

38,

39]. Some Indigenous people work in different governmental, private, tourism, or conservation sectors [

38,

41]. Despite various economic opportunities, most Sungai people today still practice traditional livelihoods to sustain their daily living [

41]. Conventional farming and fishing highly depend on climate, rendering them susceptible to climate hazards.

The Malaysian government implemented poverty reduction strategies over the past decades to improve the livelihoods of Indigenous peoples throughout the nation [

42]. Nevertheless, this Indigenous population remains socio-economically marginalized [

42]. In Sabah, they are denied native land customary rights. The majority of residents accept partial recognition of official land ownership, yet their lives and survival are dependent on it. The Indigenous communities in Kinabatangan have limited access to basic amenities, such as a clean water supply. Some areas in the Kinabatangan cannot be reached by road. The communities have to cross over the Kinabatangan River using a boat or ferry [

43]. In 2005, the Sabah government established Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary and enforced Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997, which resulted in limited access to hunting and harvesting natural resources [

44]. A proposal has been made to build a 350 m bridge to connect Sukau village to opposite villages across the vast Kinabatangan River. The bridge and paved roads are necessary for economic development in this area [

43]. However, this suggestion sparked controversy among Kinabatangan stakeholders, including local and international conservationists. They have great concerns that the bridge would cause significant landscape changes and the potential risk of wildlife extinction when large-sized animals cannot migrate through fragmented landscapes [

45]. In 2017, the Sabah government discarded this plan, resulting in a public protest by some Indigenous communities [

46]. The marginalization of Indigenous peoples, insufficient access to proper amenities, and the conservation pressure are compound issues that challenge the survival and livelihoods of the natives in this region.

3. Climate Change Impact and Adaptation

The Kinabatangan area is well known for spectacular but critically endangered wildlife species, such as the Bornean orangutan, Bornean elephant, and the proboscis monkey. These animals attract local and international tourists to view the animals in their natural habitat [

38,

41]. These animals can be seen along the Kinabatangan River during the driest season between March to September. Few tourists come to the Kinabatangan from December to January because of heavy rain leading to flooding; thus, the villagers obtain lower incomes. Globally, the diminution of biodiversity is related to increases in extreme weather events, barriers to dispersal, and changes in trophic levels [

47]. For example, cyclones can alter the onset of sexual maturity in turtles, floods can reduce plant species richness, and prolonged droughts have caused population collapse in koalas [

48]. In Kinabatangan, extensive forest conversion to oil palm plantations has resulted in significant habitat loss and fragmentation, leading to biodiversity loss [

31,

33]. Habitat loss and climate change can act synergistically, thus amplifying their negative impacts on biodiversity [

34]. Orangutans in the Kinabatangan feed primarily on fruits. The reduction in natural food sources during a prolonged drought can lead the orangutans to starvation and aggravate human-wildlife conflict when they resort to entering villagers’ orchards to search for food [

31,

32]. Increased drought periods negatively affect tree survival, while warm temperature adversely affects fish species by correlating with disease proliferation [

49]. The anthropogenic impacts on the biodiversity resources, coupled with a changing climate, have negatively affected the Kinabatangan tourism industry because the flagship attraction is wildlife [

38,

50]. Kinabatangan also attracts international organizations for conservation work such as tree planting in Batu Puteh and Sukau villages [

31].

Other pressing issues occurring in the Kinabatangan are climate-related phenomena such as floods and forest fires, though the climate influences the latter indirectly. The communities in the Kinabatangan depend much on the Kinabatangan River and surrounding aquatic water resources for their livelihoods and domestic water consumption [

51]. Unfortunately, timber logging in upstream Kinabatangan areas deteriorates water quality and increases flood risk due to changing hydrology. In addition, land clearance for oil palm plantations causes severe soil erosion, and the resultant displaced soil is washed into the Kinabatangan River [

33]. During dry periods and less rainfall, the communities encounter a shortage of clean water supply. Seasonal floods are primarily linked to human factors and activities in land use. However, heavy rain also raises the water level of the Kinabatangan River, leading to severe flooding, which can cause human death, property damage, and economic loss [

52]. The Indigenous communities encounter recurring floods with occasional landslides every year. Forest fires have significant effects on biodiversity resources. For example, a massive fire destroyed about 200 hectares of Kinabatangan forest reserve in 2016; as commented by a conservationist, “Over the years, a huge amount of resources, such as time and money, have been spent by many stakeholders to conserve Kinabatangan biodiversity, there is still more that needs to be done to ensure that wildlife, forest, and Kinabatangan peoples can exist in harmony and benefit each other. Everybody loses if decades of hard work and dedication go up in smoke” [

53] (p. 2). The recurring incidence of forest fires is commonly observed to be related to hunters utilizing unsustainable methods to drive animals out of their hiding places. During a drought season, dry and strong wind spread the fire to an adjacent sanctuary and Indigenous settlement [

44]. Lessons learned from these issues are that the hazards can cause significant damage to Indigenous lives, properties, and natural resources. There is a need to engage the communities to solve this problem and participate in local climate adaptation.

The Malaysian government has included specific guidelines designed to address climate change impacts in the National Policy on Climate Change and the Malaysia Plans. However, many of the strategies prioritize mitigation over adaptation plans, such as promoting energy efficiency among the public and reducing GHG emissions [

54]. At the national level, critical areas that require adaptation are agriculture, drought, flood, erosion, forest, biodiversity, and coastal marine habitat. Initiatives undertaken by the Malaysian government include increasing awareness among the public across the nation, such as the launching of an official website known as ‘Infobanjir’ (flood) and ‘InfoKemarau’ (drought) to provide information on forecasting and monitoring of both hazards, including to facilitate emergency responses [

55]. There is a weather observation and radar station in the Sandakan Meteorological Office, which produces daily weather forecasts for Kinabatangan and early warnings of adverse weather phenomena, such as continuous heavy rain, thunderstorms, drought, strong winds, and haze. Several strategies undertaken to adapt to climate change impacts are: to improve drainage in Kinabatangan areas vulnerable to flooding, to slow down animal population decline by increasing habitat corridors, and quick responses from the District Disaster Management Committee to evacuate flood victims to safe places [

34,

56]. However, Malaysia’s climate adaptation does not adequately incorporate Indigenous coping strategies [

54]. Understanding Indigenous perceptions of climate change impacts is critical because the government requires their knowledge to prepare for effective adaptation strategies [

16,

57].

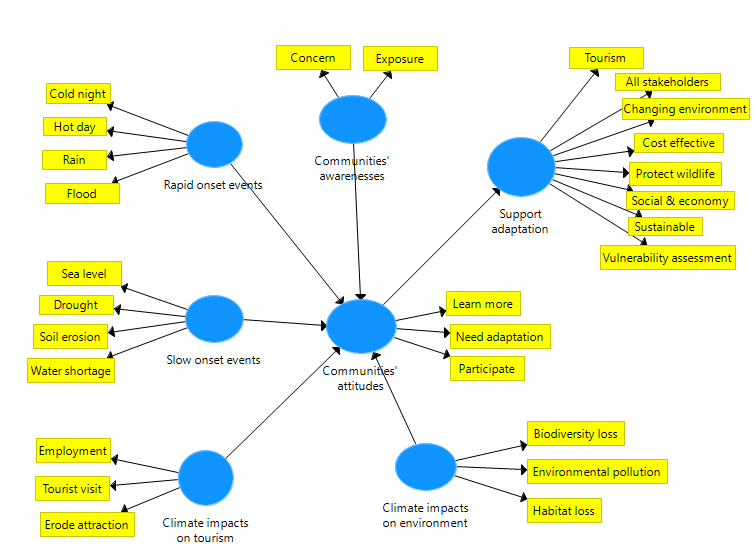

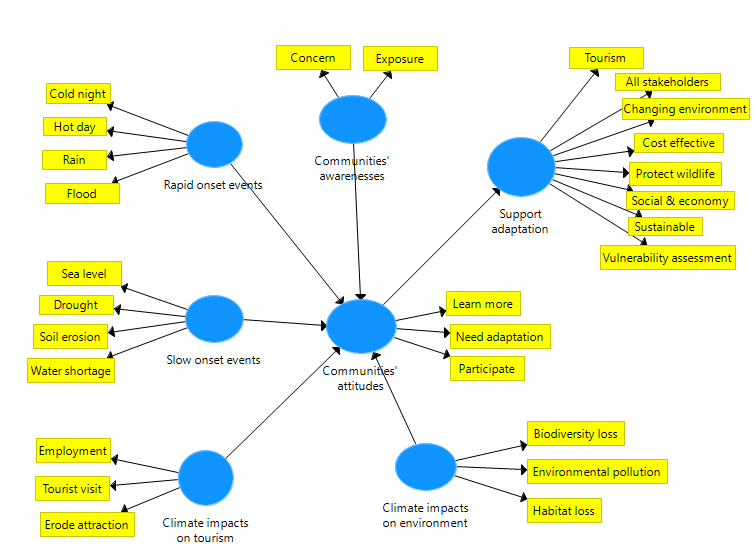

1.3. Modeling the Relationship between Communities’ Attitudes and Climate Change

We develop a research model based on the available literature to assess Indigenous peoples’ perceptions of climate change impacts in Kinabatangan (Figure 1). The process

of identifying factors related to Indigenous support for climate change adaptation was carried out in three steps. First, we conducted a literature review to assess the impacts of climate change on the Indigenous communities and how they responded to these impacts. Second, we identified factors associated with Indigenous support for adaptation from the literature, which led to the identification of seven variables: communities’ awareness, rapid onset events, slow onset events, climate impacts on tourism, climate impacts on the environment, communities’ attitudes, and support towards adaptation. Third, each construct in the model was validated through interviews with the Indigenous people. The initial confirmation of the constructs was crucial to ensure the items (e.g., cold night, hot day, drought, and rainfall) selected to form each variable (i.e., rapid onset events) were applicable to the actual climate scenario in the Kinabatangan area. The following paragraphs describe the seven constructs employed in the research model.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Communities’ awareness positively affects the communities’ attitudes in supporting climate change adaptation.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Slow onset events positively affect the communities’ attitudes in supporting climate change adaptation.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Rapid onset events positively affect the communities’ attitudes in supporting climate change adaptation.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Climate impacts on tourism positively affect the communities’ attitudes in supporting climate change adaptation.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Climate impacts on the environment positively affect the communities’ attitudes in supporting climate change adaptation.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Communities’ attitudes have a positive effect on communities’ support for climate change adaptation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

This study was conducted at Sukau and Batu Puteh villages in the Kinabatangan Sabah (Figure 2). There were 226 houses in Sukau village and 178 houses in Batu Puteh

village, amounting to 404 houses [43]. We employed a case study research methodology and purposive sampling to select respondents in both villages [67,68]. The study also employed a quantitative approach, using 404 self-administered questionnaires distributed to each house in both villages. Purposive sampling was employed by requesting a leader from each house to take part in the survey. This approach was crucial because the leaders obtained incomes for their families through subsistence livelihoods and were often responsible for attending meetings to discuss various village matters, including livelihoods and climate change in the villages. Traditionally, the house leader was an adult male, except when married women had lost their husbands; in this situation, the married woman was regarded as the house leader. If the house leader was found not to be available at home during the research because of sickness or being away from the Kinabatangan, a house representative aged 18 years or older was invited to participate in their stead. If the representative surveyed was not a house leader, caution was exercised by writing notes and asking the representative for background information about the house leader. Additionally, if no one was at home during an attempted research visit, the researchers revisited the same house at a later time or date. The survey questions were structured based on previous studies [20,69,70]. The questionnaire was pre-tested with the communities in this area and subsequently changed according to their comments. The questions were used to assess seven variables: communities’ awareness (CA), rapid onset events (ROE), slow onset events (SOE), climate impacts of tourism business (CIOT), climate impacts of the environment (CIOE), communities’ attitudes (CAT), and support adaptation (SA). Each survey question was given a 5-Likert scale answer (Supplementary Questionnaire S1). One open-ended question was added at the end of the survey, which asked the respondents’ opinions on climate change in this area: Please write your opinions regarding the effects of climate change and suggestions to solve this problem.

2.2. Data Analysis

The data obtained from the quantitative method were analyzed using partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) of the SmartPLS version 3.3.2 (Oststeinbek, Germany) [71]. The PLS-SEM is a multivariate analysis that assesses the reliability and validity of constructs, including analyzing the relationships among all variables in a research model. The usage of PLS-SEM was appropriate in this study because the research focused on exploring new concepts of factors influencing the communities’ support for climate change adaptation, including its purpose in predicting and identifying a key driver construct in Kinabatangan Sabah [30]. The PLS-SEM can estimate complex interrelationships simultaneously and is well known for predicting success factor studies [72].

3. Results

3.1. Profile of Respondents

The profile of respondents was assessed based on gender, age, ethnicity, and occupation. Out of 404 distributed surveys, the study gathered 328 completed questionnaires

which showed an 81% response rate. As we employed the purposive sampling, the respondents comprised more males (60.7%) than females (39.3%). The respondents were aged 18 to 30 years (37.8%), 31 to 49 years (48.5%), and above 50 years (13.7%). For ethnicity, 75.9% of respondents were Sungai people, while 24.1% were mixed ethnics ofMalay, Kadazan/Dusun, and Bugis. Despite broad opportunities in the tourism business, only 5.2% of respondents worked in the tourism sector while most respondents engaged in subsistence livelihoods such as farming and fishing (25.6%), the conservation sector (25.3%), an established personal business (14.3%), and government staff (6.1%), and 23.5% of respondents were unemployed.

3.2. Assessment of the Model Using PLS-SEM

3.2.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

Most indicators loaded higher than 0.7 on the respective latent variable, while five indicators loaded between 0.6 and 0.7 (Table 1). Hair et al. [29] state that indicators with

loading between 0.4 and 0.7 can be retained if their CR and AVE values exceed the threshold of 0.7 and 0.5 for adequate indicator reliability, respectively. Therefore, all indicators were kept in this study because the CR and AVE values for the seven constructs met the requirement for indicator reliability.

The respondents reported climate hazards negatively affecting their survival and livelihoods. However, they also related loss of livelihoods to non-climate factors such as strict conservation rules and animal crop-raiding. They obtained information on climate and weather from social media such as television, radio, and online website. Field observation and personal communication with the Kinabatangan local authorities confirmed an absence of climate change adaptation plans explicitly developed for this region. The respondents reported that the communities’ leaders were responsible for discussing matters with the local authorities at the Kinabatangan district and state levels. The villagers were only informed after the discussion. Approaches undertaken were to post warnings of flood and thunderstorms on the Sabah Meteorological Department’s official website and prepare for evacuation in times of flooding. There seemed to be no specific plans to address these climate-related livelihood issues in tourism, subsistence farming, and fishing to assist in adjusting to the changing drought and rainy season. According to their understanding of changing weather, suitable soil, and correct methods of planting and harvesting, the Sungai people use traditional knowledge to plant and harvest oil palms and fruits. Local authorities identified high-risk forested areas susceptible to fires, and increased monitoring and preparation to extinguish the fire to protect the natural resources.

The respondents were determined to describe the climate change impacts they experienced in this area. However, they could not identify any specific adaptation strategies

to address these effects or reduce their vulnerability to climate hazards. The majority of respondents (n = 243, 74.1%) stated that there was a necessity to start adaptation plans to lessen the impacts. Some respondents commented that specific action was employed only after the occurrence of climate events. For example, when drought or flooding led to the disruption of clean water supply to the villages. Nevertheless, only after it occurred the water supply was distributed to the villagers. Another challenge was the clean water supply delivery to remote areas that could not be accessed by roads. The respondents recommended that: (1) Initiate evaluation of climate hazards and impacts; (2) establish a platform for robust and open discussion between the villagers, authorities, tourism enterprises, conservation researchers, NGOs, and private sectors, and; (3) to outline specific adaptation plans for the Kinabatangan by referring to the national adaptation strategies.

4. Discussion

This study investigates Indigenous peoples’ perceptions of climate change impacts in the rural Kinabatangan. In particular, our research model shows how climate factors and

communities’ attitudes influence Indigenous support and participation in climate change adaptation. The findings show that communities’ awareness positively and significantly affects the communities’ attitudes towards climate change adaptation (H1). The respondents with higher awareness and prior exposure to climate change impacts were more likely to support climate adaptation in this region. Indigenous awareness and personal acknowledgment of climate change are the most crucial factors determining their decisions to employ adaptation measures [9,84]. Our results show that the Sungai people rely on traditional knowledge to resume subsistence livelihoods under prolonged drought and heavy rainfall [2,85]. In Kinabatangan, however, having Indigenous knowledge does not necessarily translate into adjusting actions in changing environments. Constant exposure to changing climate can alter Indigenous peoples’ awareness and concern, influencing their traditional knowledge to adapt to climate change. Indigenous awareness of climate change impacts and concern about the frequency and intensity of climate hazards determine the Sungai peoples’ attitudes on engaging in the adaptation. This finding implies that local authorities can apply this factor by providing scientific climate information and adaptation guidelines to ensure the communities respond appropriately to the impacts, thus improving adaptation outcomes in this region [12].

Respondents who score rapid onset events (ROE) due to hot days, cold nights, floods, and heavy rain have a positive and significant effect on the communities’ attitudes, implying that they support climate change adaptation (H2). However, the slow onset events (SOE), measured by soil erosion, sea-level rise, prolonged drought, and water shortage, insignificantly affect the communities’ attitudes (H3). The findings show that the frequency and intensity of changing weather have a substantial impact on Indigenous peoples’ perspectives. This in turn determines their support for climate adaptation. Our results are consistent with previous studies that show that Indigenous communities perceive erratic rainfall, increasing warming temperature, and drought as obvious signs of changing weather patterns [1,3,14]. Extreme weather (ROE) is a prominent indicator for the Sungai people to support climate actions more than the SOE factor that occasionally occurs.

Previous studies illustrated that climate hazards could cause varying levels of damage to Indigenous livelihoods. Flooding is rated the most disastrous hazard by Indigenous

communities involved in farming [14]. Erratic rainfall causes low agricultural output and changes livelihoods [1]. While we acknowledge the contribution of these studies in understanding Indigenous peoples’ perceptions of climate change, these findings can be improved by considering the interaction between different climate factors on Indigenous communities’ livelihoods. Using PLS-SEM, all interacting factors are analyzed simultaneously, thus producing more consistent estimates and reducing standard errors [30,72]. In this study, the PLS-SEM identifies the ROE as a significant factor among the seven constructs included in the modeling. Therefore, the Sabah government could focus programs and policies on the ROE factor, which the communities deem essential to garnering their support and participation in Kinabatangan climate adaptation.

The climate impacts on tourism (CIOT) positively and significantly affect the communities’ attitudes (H4). Conversely, we do not find a significant relationship between

the climate impacts on the environment (CIOE) and the communities’ attitudes (H5). The climate change burden negatively affects the socioeconomics of rural Indigenous communities. Extreme climates such as prolonged drought and heavy rainfall reduce agricultural yield and fish catchment in the Kinabatangan River. Climate change impacts on environmental resources are varied, and Indigenous peoples rely heavily on these resources, which are vulnerable to a changing climate [20,64]. However, not much is known regarding what type of resources determine Indigenous peoples’ perception to support climate action. This study fills this gap by understanding that the Kinabatangan communities prioritize the effects on different aspects such as reduced tourism revenue, biodiversity loss, and climate-related health problems. They make a distinction on the economic aspects – they perceive natural resources explicitly related to their livelihoods as more critical than other resources not related to their financial loss. In other words, loss of wildlife affects tourism revenue, and reduced crop yields are more alarming than vegetation and forest cover destruction. We found the divergences related to prior exposure to media communications [86]. Such differences are also shaped by their roles and experiences working in particular organizations. The respondents who work in the conservation sector link the impacts with biodiversity values, but those working in tourism enterprises worry more about its consequences on tourism employment and revenue. Studies that examine the effects of economic and environmental factors on Indigenous support for climate actions are limited [87,88], but this study provides evidence of economic importance in encouraging Indigenous peoples’ participation in coping with climate impacts.

Despite the initiatives undertaken by the Malaysian government, our findings reveal that a practical approach to adapting to climate change impacts is not communicated well to rural dwellers, such as in the case of the Sungai people in the Kinabatangan, Sabah. The Indigenous communities report noticeable effects of changing climate, but they are not aware of specific adaptation strategies to solve this problem. The Indigenous peoples’ expression of lack of knowledge on readily available initiatives to cope with the effects is an opportunistic area for immediate attention. This study contradicts Tunde and Ajadi [3], who report that Indigenous communities are given early warnings and employ different local adaptation strategies to cope with climate impacts. The lack of knowledge in responding to specific climate events could undermine a sustainable approach to coping with recurring climate change impacts. Common factors attributed to low awareness of climate change among Indigenous peoples are marginalization, limited access to education, poor communication, and top-down institutional processes that allow little Indigenous voice [20,21,89]. In Kinabatangan, our findings reveal that the communities are only informed after the planning and decision-making with government authorities. This scenario exhibits a fragmented, top-down approach that excludes Indigenous involvement, thus reducing adaptation acceptance. The Malaysian government needs to encourage the participation of marginalized Indigenous communities in dealing with the climate effects to reduce poverty resulting from the loss of economic revenue because of climate hazards [42]. Strategies to cope with climate change impacts are likely to fail due to knowledge gaps that exist when a local community is excluded during a planning process [13,90]. Therefore, the top-down approach requires changes by acknowledging everyone’s equal right to participate in planning and decision-making. Recognizing the valuable contributions that Indigenous communities can make using their unique local knowledge could assure that each individual across the country can express their opinions and holistically receive climate change messages.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for different climate scenarios, as Indigenous communities in different regions, due to differences in culture, economic activities, and environment, experience varying levels of climate hazards [12,13]. Climate change adaptation policies that involve contradictory perspectives are complicated, but workable strategies are possible if planned based on local needs and consequences. Our research model shows that the respondents who view the factors related to support adaptation [H6] positively are more inclined to solve the climate issues in this area. However, any climate action should consider local needs, such as multiple social, economic, and cultural benefits for local communities. Other critical criteria to consider for the uptake of Kinabatangan climate change adaptation are the engagement of all Kinabatangan stakeholders, protection of the natural and tourism resources, adapting to a changing environment, and inclusion of vulnerability assessments. Overall, this study provides early guidelines for the Kinabatangan stakeholders, policymakers, and the Sabah government to pay extra attention to the adverse climate effects and the lack of adaptation actions. While this study focuses on Indigenous communities and climate change impacts, the adaptation strategies should include the interaction between climate change and natural resources conservation and the tourism sector. Careful planning is critical considering that this area has a complex interplay between biodiversity conservation, Indigenous reliance on depleting natural resources, wildlife-based tourism, and extensive land clearance, all of which place this area as highly vulnerable to climate hazards [32,91]. As the majority of the Sungai people live in this region, their perspectives are essential for the adaptation plans, and they should be included throughout the adaptation planning process.

Previous studies use meteorological data and climate projection models to examine Indigenous peoples’ perceptions of climate change impacts, which have contributed to a greater understanding of Indigenous vulnerability and adaption to changing climate [1,14,26,85]. Some studies apply PLS-SEM to examine climate change impacts in various aspects [92,93], but these studies are not focusing on Indigenous peoples’ perceptions. The Kinabatangan study is one of the few studies applying the PLS-SEM modeling to assess attitudinal factors influencing Indigenous support for climate adaptation. Using this modeling, we identify the communities’ attitudes as the most influential factor determining their support for climate adaptation, followed by the communities’ awareness, rapid onset events, and climate impacts on tourism. These findings will help the Sabah government improve climate adaptation by promoting Indigenous peoples’ participation in initiatives that address climate impacts in the Kinabatangan and throughout the state. The results demonstrate that the government needs to provide scientific knowledge and management support to the Indigenous peoples, improving their awareness and focusing on the economic sector that the communities perceive severely affected by climate hazards. For example, the Kinabatangan authority can apply the CIOT factor to garner more support from the villagers in executing climate intervention. This is because of the more severe impacts of climate on the tourism sector, making the attitudes of the communities to support and participate more apparent. As this study provides early findings on the climate change issue, more research is needed to fine-tune adaptation strategies for the Kinabatangan Indigenous peoples.

For methodological implication, the model identifies significant factors that influence the Indigenous support for climate adaptation, but it overlooks other impacts such as

climate-related health problems. Therefore, adding one open-ended question to the questionnaire assists in explaining factors that are not measured in the research model. This approach offers better explanations of Indigenous peoples’ perceptions of ‘what impact, how if affects, and why it happens.’ For instance, the CIOT factor is significant, though only a few respondents working in tourism are involved in this study; this ambiguity can be validated by checking the respondents’ comments in the open-ended question. Evidence shows that some respondents work as farmers, but they write comments about climate impacts on tourism in the open-ended question section. One probable reason for this is that while the respondents answering the survey are not themselves working in tourism and instead do subsistence work, they considered family members who have worked in this sector, such as homestay, housekeeping, and cooking. They consider the impacts of climate change on overall family income. The current study does not include gender analysis in the modeling, but this component can influence adaptation outcomes [16,57]. This information serves as a precaution for future researchers who seek to apply the PLS-SEM modeling technique to identify factors influencing Indigenous peoples’ attitudes towards supporting climate change adaptation in different areas of study.

The Conference of the Parties (COP) is the highest decision-making body of the UN Convention Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) [94,95]. Parties will

discuss progress in adaptation to the impacts of climate change and the approaches to address loss and damage associated with these impacts. Developing countries will make suggestions for a global goal for adaptation and point out the importance of financial, technology, and capacity-building support. The UNFCCC defines adaptation more broadly as adjustments in ecological, social, or economic systems in response to climate change impacts [95]. Five components of adaptation activities are: observation; assessment of climate impacts and vulnerability; planning; implementation; and monitoring and evaluation of adaptation actions [94]. In this study, current approaches to dealing with climate impacts in Kinabatangan are inadequate and unsustainable in the long term. Coping mechanisms are developed only in the aftermath of major climate events, and Indigenous peoples do not undertake adaptation actions to deal with the negative consequences. Despite the evidence of absent climate change adaptation plans, the Sungai people are supportive and describe an urgent need to initiate adaptation actions. The PLS-SEM method provides new perspectives by highlighting the importance of incorporating climate stressors and attitudinal factors into adapting to climate change. Previous approaches focused largely on addressing climate hazards in developing Indigenous adaptation strategies [1,14,23,24]. The current study recommends that non-climate factors such as Indigenous peoples’ awareness, attitudes, and livelihoods be included in the adaptation plans to secure Indigenous support and active participation in coping with the climate impacts. In line with the COP, the Kinabatangan study shows an important need for capacity-building support from top management authorities to the communities and incorporates the five components of

adaptation activities to address the climate issues in this region.

5. Conclusions

The study contributes to the literature on understanding the factors that influence Indigenous support for climate change adaptation in rural areas. There are three major

findings in this study. First, the respondents concur that climate change has affected their villages, but they prioritize the negative impacts on their health and economy. Second, the intensity of rapid-onset events and decreased tourism revenue influence the communities’ support for climate adaptation. Third, the Indigenous communities cannot identify coping strategies for climate hazards in their villages. Overall, this research contributes to a growing body of knowledge about the factors influencing Indigenous support of climate change adaptation in rural areas. The PLS-SEM provides a rigorous analysis to identify the key predictors of multiple factors affecting

Indigenous peoples’ perceptions by simultaneously assessing all relationships among the seven variables in the Kinabatangan area. The findings show both climate stressors and non-climate factors have different impacts on the Sungai peoples’ support for climate change adaptation. In Kinabatangan, the strongest predictor is the Indigenous peoples’ attitudes, followed by their awareness, rapid onset events, and climate impacts on tourism. Therefore, climate change adaptation policies must take a more holistic approach by integrating these factors to acquire effective adaptation that addresses the vulnerability of Indigenous peoples in remote areas.

There are some drawbacks to this study. This study was conducted on a single Indigenous population in Kinabatangan, Malaysia. Hence, it may not be possible to generalize the findings to other Indigenous communities. Future research should incorporate other factors that are applicable to local Indigenous peoples who live in certain destination areas.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14116459

1. Introduction

1. Introduction