Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) continues to be the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the US. Colonoscopy remains the best preventative tool against the development of CRC. As a result, high-quality colonoscopy is becoming increasingly important.

- colorectal cancer

- CRC

- high-quality colonoscopy

1. High-Quality Colonoscopy Component 1: Patient Education

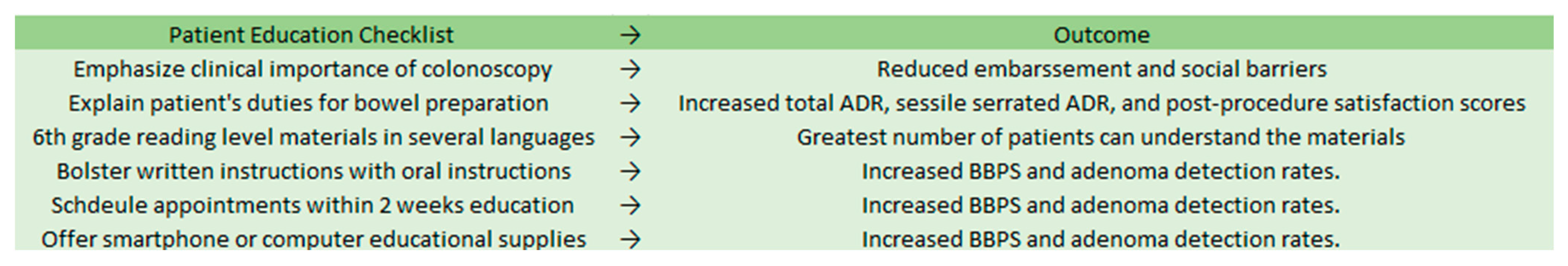

Patient education and an understanding of the pre-procedure preparation and the procedure itself are key for better colonoscopies. Providers should educate their patients on the importance of routine colonoscopy and how bowel preparation contributes to a successful procedure. Failure to educate patients causes worse bowel preparation and less adherence to routine colonoscopy schedules.

Patients’ motivation to receive a routine colonoscopy may be lower if they do not understand the clinical importance, subsequently leading to delayed cancer diagnosis. A 2020 survey by Amlani et al. on colonoscopy across Europe showed that 72% of responders were receptive to colonoscopy if their doctor advised undergoing one, yet only 45% understood its importance in preventing colorectal cancer [1]. Studies have shown that patient education can increase patient satisfaction and ADR. A 2020 meta-analysis by Tian et al. reviewed studies comparing outcomes in colonoscopy patients who received little or no patient education to outcomes of patients who received enhanced patient education. They found that enhanced patient education materials were associated with a significant increase in the polyp detection rate (PDR), ADR, and the sessile serrated adenoma detection rate (SSADR) [2].

The readability of educational materials increases patient understanding. A 6th-grade reading level is recommended to assure comprehension by the greatest number of patients [3]. Furthermore, language barriers must be assessed and addressed. All offices should provide written instructions in English, Spanish, and other commonly spoken local languages. Greater education interventions may be required in elderly patients, those with impaired cognitive functioning, and those with hearing problems. Recurrent reminders and involving caretakers are effective ways to increase adherence to bowel preparation routines in elderly patients and patients with cognitive difficulties.

Enhancing written patient instructions with verbal instructions from a medical professional significantly improves patient adherence to bowel preparation routines. One study showed that intensive patient educational programs led by pharmacists improved patient compliance, tolerability, and acceptability of a split-dose bowel regimen, leading to greater rates of optimally prepared colons (n = 300, p < 0.001) [4].

A 2018 study by Lee et al. demonstrated that shorter waiting times from patient education to colonoscopy improved the quality of bowel preparation [5]. The Total Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) scores for patients whose procedures were performed within 2 weeks of education were significantly higher than those of patients whose procedures took place more than 2 weeks after education (n = 130, p = 0.017).

Computer-based educational materials are also methods to improve bowel preparation and overcome social barriers. Although sample size continues to be an issue in studies on computer-based bowel preparation education materials, these educational materials have been shown to be non-inferior to traditional written instructions when measuring bowel preparation [6][7][8]. A 2021 multicenter randomized controlled trial by Veldhuijzen et al. analyzed 684 patients educated by nurses or computer-based education [9]. Adequate bowel cleansing was seen in 93.2% of computer-educated patients compared to 94.0% of nurse-educated patients. Computer-based education can be an efficient and cost-effective educational tool to improve bowel preparation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Patient education checklist and expected outcomes.

2. High-Quality Colonoscopy Component 2: Bowel Preparation

Validated scales should always be used for documenting bowel preparation. Without using validated scales, comparing bowel preparation between patients is unreliable and biased. The five most widely used scales are the Aronchick Scale, Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale, BBPS, Harefield Cleansing Scale, and the Chicago Bowel Preparation Scale [10]. Of these scales, the BBPS has the largest amount of reliability and validation data supporting its efficacy.

The BBPS, designed in 2009, is a 10-point scale that assesses bowel preparation after all cleansing maneuvers are completed [11]. The scale removes subjective terms, including “excellent, fair, or poor”, from its criteria and instead grades each section of the colon on a scale from 0 to 3. The sections that are scored include the right colon, transverse colon, and left colon. These scores are summated for a total score of 0 to 9, with a higher score indicating that more mucosa is visualized because less stool is covering it. Providers should aim for a total score greater than or equal to 6, with a score of 2 or more per segment.

Proper bowel preparation requires adherence to a low-residue or clear liquid diet. A low-residue diet may be favored since it is frequently preferred by patients over the clear liquid diet [12]. A 2019 randomized clinical trial comparing a low-fiber diet to a clear liquid diet found that patients who consumed a low-fiber diet the day before a procedure had a better perception of hunger and felt less hungry compared with those who had a clear liquid diet [13]. Adequate bowel preparation was achieved in 89.1% and 95.7% of patients in the clear liquid diet and low-fiber diet groups, respectively, showing both noninferiority and superiority (p = 0.04) of the low-fiber diet [13]. There were no significant differences in cecal intubation rate, whole-polyp detection rate, proximal colon polyp ADR, or distal colon ADR.

When determining the appropriate number of days to follow a low-residue diet, there was no significant difference in bowel preparation quality between the 1-day versus the 2-day diet. A 2020 study by Jiao et al. found comparable BBPS scores between the two groups (p > 0.05) [14]. There were similar colonoscopy insertion times, withdrawal times, and PDRs. It should be noted that patients following a 1-day diet reported significantly easier compliance than those in the 2-day group. In conclusion, 1-day low-residue diets produce statistically similar bowel preparedness scores compared with 2-day low-residue diets while increasing patient compliance and satisfaction.

Osmotic laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), are used as a standard component of bowel preparation in the US. Randomized clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of split-dose versus single-dose preparations have shown that split-dose produces more adequately empty and cleanse bowels [15]. PEG 4L solution, oral sulfate solution, 2L PEG and ascorbate, and magnesium citrate and sodium picosulfate are four of the most commonly used laxatives for bowel preparation. A 2021 prospective randomized study by Kmochova et al. showed no significant difference in Boston Bowel Prep Scores between the four groups [16]. The best-tolerated solution was magnesium citrate and sodium picosulfate, with lower rates of nausea and higher rates of palatability [16].

Intolerable taste or texture can deter patients from completing bowel preparation. Oral sulfate tablets can be used for patients with sensitivities to textures and tastes. Randomized control trials have shown oral sulfate tablets to be just as safe and efficacious as PEG and ascorbate [17].

Slowed gastric mobility can interfere with bowel preparation. This could occur in patients with diabetes, chronic constipation, opioid use, and older age. Chronically constipated patients with rectal pain during defecation and start-to-defecation intervals of over 4 h were shown to have significantly higher rates of inadequate bowel preparation than other chronic constipation patients lacking these symptoms [18]. For diabetic patients, opioid users, and the elderly, higher doses of laxatives may be required.

3. High-Quality Colonoscopy Component 3: Proper Scoping Equipment and Contrast

Advances in endoscopy have allowed for higher-definition imaging. Traditional standard-definition endoscopes typically operate in the range of 100,000 to 400,000 total pixels displayed in a 4:3 aspect ratio [19]. High-definition endoscopes operate at over 1 million total pixels, providing aspect ratios beyond 4:3 to accommodate screens of larger widths. Furthermore, high-definition monitors can have frame rates of over 60 times per second, meaning that the image is redisplayed rapidly to create a more realistic and accurate image of the colon. Lastly, high-definition scopes have increased magnification abilities, allowing for a far more detailed image than is possible with standard-definition endoscopy. Standard-definition endoscopes are being replaced by high-definition endoscopes that produce better resolution, making it less likely to miss adenomas. In a 2019 study by Roelandt et al. comparing standard-definition white light endoscopy with high-definition white-light endoscopy, high-definition coloscopy resulted in significantly higher detection rate of sessile serrated adenomas (8.25% vs. 3.8%; p = 0.01) and adenocarcinomas (2.6% vs. 0.5%; p < 0.05) [20]. However, it should be noted that no significant difference in ADR or adenoma per colonoscopy rate (APCR) was seen between high-definition and standard-definition colonoscopy. Overall, high-definition colonoscopy equipment should be used to better detect important diagnoses.

Increasing mucosal contrast increases adenoma detection rates. Several methods are available for increasing mucosal contrast, including traditional dyes and computerized electronic virtual chromoendoscopy. These chromoendoscopy techniques allow neoplasia to be detected more easily by the endoscopist. Pan-colonic chromoendoscopy using a dye, such as a 0.4% indigo carmine spray, is one of the more commonly utilized approaches. Computerized virtual chromoendoscopy utilizes post-processing filter algorithms or a rotating filter in front of the light source to create real-time contrast and enhanced visualization of tissue vasculature and surface neoplasia [21]. A 2010 study by Pohl et al. of 1008 patients performed standard endoscopy followed by dye-enhanced colonoscopy. The proportion of patients with at least one adenoma was significantly greater in the group that received dye (46.2% vs. 36.3%; p = 0.002). Furthermore, chromoendoscopy patients had an increased overall detection rate for adenomas (0.95 vs. 0.66), flat adenomas (0.56 vs. 0.28), and serrated lesions (1.19 vs. 0.49) (p < 0.001) [21]. A 2018 randomized trial by Iacucci et al. demonstrated that virtual computerized chromoendoscopy neoplastic detection rates were non-inferior to dye-based chromoendoscopy detection rates [22]. Therefore, so long as the endoscopist uses a contrast of any sort, the outcomes are better for the patient.

Although computer-assisted detection, such as GI Genius, is not available to most endoscopists, these technologies increase adenoma detection rates and decrease missed colonic neoplasia rates. Randomized control trials have shown increased ADR when utilizing artificial intelligence rather than using high-definition white light colonoscopy alone [23]. Computer-aided detection (CADe) has also been shown to have higher detection rates of sessile serrated lesions. CADe also does not cause a significant increase in withdrawal times compared with other techniques. This technology should become more widespread and accessible in the coming years.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/gastroent13020017

References

- Amlani, B.; Radaelli, F.; Bhandari, P. A survey on colonoscopy shows poor understanding of its protective value and widespread misconceptions across Europe. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233490.

- Tian, X.; Xu, L.-L.; Liu, X.-L.; Chen, W.-Q. Enhanced patient education for colonic polyp and adenoma detection: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17372.

- Stossel, L.M.; Segar, N.; Gliatto, P.; Fallar, R.; Karani, R. Readability of patient education materials available at the point of care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1165–1170.

- Janahiraman, S.; Tay, C.Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lim, W.L.; Khiew, C.H.; Ishak, I.; Onn, Z.Y.; Ibrahim, M.R.; Chew, C.K. Effect of an intensive patient educational programme on the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy: A single-blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020, 7, e000376.

- Lee, J.; Kim, T.O.; Seo, J.W.; Choi, J.H.; Heo, N.-Y.; Park, J.; Park, S.H.; Yang, S.Y.; Moon, Y.S. Shorter waiting times from education to colonoscopy can improve the quality of bowel preparation: A randomized controlled trial. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 29, 75–81.

- Back, S.Y.; Kim, H.G.; Ahn, E.M.; Park, S.; Jeon, S.R.; Im, H.H.; Kim, J.-O.; Ko, B.M.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, T.H.; et al. Impact of patient audiovisual re-education via a smartphone on the quality of bowel preparation before colonoscopy: A single-blinded randomized study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 87, 789–799.e4.

- Zander, Q.E.W.v.d.; Reumkens, A.; van de Valk, B.; Winkens, B.; Masclee, A.A.M.; de Ridder, R.J.J. Effects of a personalized smartphone app on bowel preparation quality: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e26703.

- Wen, M.-C.; Kau, K.; Huang, S.-S.; Huang, W.-H.; Tsai, L.-Y.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Tsay, S.-L. Smartphone education improves embarrassment, bowel preparation, and satisfaction with care in patients receiving colonoscopy: A randomized controlled trail. Medicine 2020, 99, e23102.

- Veldhuijzen, G.; Klemt-Kropp, M.; Droste, J.S.T.S.; van Balkom, B.; van Esch, A.A.J.; Drenth, J.P.H. Computer-based patient education is non-inferior to nurse counselling prior to colonoscopy: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy 2020, 53, 254–263.

- Kastenberg, D.; Bertiger, G.; Brogadir, S. Bowel preparation quality scales for colonoscopy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2833–2843.

- Calderwood, A.H.; Jacobson, B. Comprehensive validation of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 72, 686–692.

- Stolpman, D.R.; Solem, C.A.; Eastlick, D.; Adlis, S.; Shaw, M.J. A randomized controlled trial comparing a low-residue diet versus clear liquids for colonoscopy preparation: Impact on tolerance, procedure time, and adenoma detection rate. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 48, 851–855.

- Alvarez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Pantaleon, M.; Roux, J.A.F.-L.; Zaffalon, D.; Amorós, J.; Bessa, X.; Seoane, A.; Pedro-Botet, J. Randomized clinical trial: A normocaloric low-fiber diet the day before colonoscopy is the most effective approach to bowel preparation in colorectal cancer screening colonoscopy. Dis. Colon Rectum 2019, 62, 491–497.

- Jiao, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, X.; Meng, X.; Zhao, L. Comparison of the effect of 1-day and 2-day low residue diets on the quality of bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 137.

- Mohamed, R.; Hilsden, R.J.; Dube, C.; Rostom, A. Split-Dose Polyethylene glycol is superior to single dose for colonoscopy preparation: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 2016, 3181459.

- Kmochova, K.; Grega, T.; Ngo, O.; Vojtechova, G.; Majek, O.; Urbanek, P.; Zavoral, M.; Suchanek, S. Comparison of four bowel cleansing agents for colonoscopy and the factors affecting their efficacy. A prospective, randomized study. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2021, 30, 213–220.

- Di Palma, J.A.; Bhandari, R.; Cleveland, M.V.; Mishkin, D.S.; Tesoriero, J.; Hall, S.; McGowan, J. A safety and efficacy comparison of a new sulfate-based tablet bowel preparation versus a peg and ascorbate comparator in adult subjects undergoing colonoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 116, 319–328.

- Guo, X.; Shi, X.; Kang, X.; Luo, H.; Wang, X.; Jia, H.; Tao, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; et al. Risk factors associated with inadequate bowel preparation in patients with functional constipation. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 65, 1082–1091.

- Subramanian, V.; Ragunath, K. Advanced endoscopic imaging: A review of commercially available technologies. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 368–376.e361.

- Roelandt, P.; Demedts, I.; Willekens, H.; Bessissow, T.; Braeye, L.; Coremans, G.; Cuyle, P.-J.; Ferrante, M.; Gevers, A.-M.; Hiele, M.; et al. Impact of endoscopy system, high definition, and virtual chromoendoscopy in daily routine colonoscopy: A randomized trial. Endoscopy 2019, 51, 237–243.

- Pohl, J.; Schneider, A.; Vogell, H.; Mayer, G.; Kaiser, G.; Ell, C. Pancolonic chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine versus standard colonoscopy for detection of neoplastic lesions: A randomised two-centre trial. Gut 2010, 60, 485–490.

- Iacucci, M.; Kaplan, G.G.; Panaccione, R.; Akinola, O.; Lethebe, B.C.; Lowerison, M.; Leung, Y.; Novak, K.L.; Seow, C.H.; Urbanski, S.; et al. A randomized trial comparing high definition colonoscopy alone with high definition dye spraying and electronic virtual chromoendoscopy for detection of colonic neoplastic lesions during IBD surveillance colonoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 225–234.

- Spadaccini, M.; Iannone, A.; Maselli, R.; Badalamenti, M.; Desai, M.; Chandrasekar, V.T.; Patel, H.K.; Fugazza, A.; Pellegatta, G.; Galtieri, P.A.; et al. Computer-aided detection versus advanced imaging for detection of colorectal neoplasia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 793–802.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!