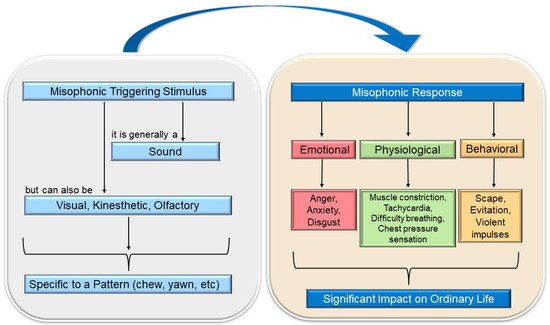

Misophonia is a scarcely known disorder. This systematic review (1) offers a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the literature since 2001, (2) identifies the most relevant aspects but also controversies, (3) identifies the theoretical and methodological approaches, and (4) highlights the outstanding advances until May 2022 as well as aspects that remain unknown and deserve future research efforts. Misophonia is characterized by strong physiological, emotional, and behavioral reactions to auditory, visual, and/or kinesthetic stimuli of different nature regardless of their physical characteristics.

- misophonia

- epidemiology

- etiology

1. Introduction

2. Triggering or Misophonic Stimulus and Symptomatology

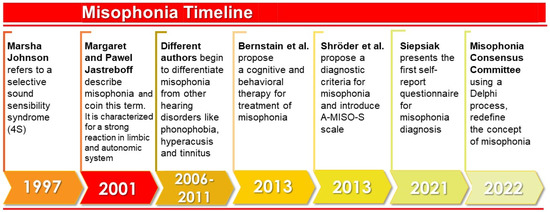

3. The Evolution of the Study of Misophonia

4. Epidemiology of Misophonia

5. Etiology of Misophonia

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph19116790

References

- Brout, J.J.; Edelstein, M.; Erfanian, M.; Mannino, M.; Miller, L.J.; Rouw, R.; Rosenthal, M.Z. Investigating Misophonia: A Review of the Empirical Literature, Clinical Implications, and a Research Agenda. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 36.

- Edelstein, M.; Brang, D.; Rouw, R.; Ramachandran, V.S. Misophonia: Physiological investigations and case descriptions. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 296.

- Jastreboff, M.M.; Jastreboff, P.J. Decreased Sound Tolerance and Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT). Aust. N. Z. J. Audiol. 2002, 24, 74.

- Jastreboff, M.M.; Jastreboff, P.J. Treatments for decreased sound tolerance (hyperacusis and misophonia). Semin. Hear. 2014, 35, 105–120.

- Wu, M.S.; Lewin, A.B.; Murphy, T.K.; Storch, E.A. Misophonia: Incidence, Phenomenology, and Clinical Correlates in an Undergraduate Student Sample: Misophonia. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 70, 994–1007.

- Siepsiak, M.; Dragan, W. Misophonia—A Review of Research Results and Theoretical Conceptions. Psychiatr. Polska 2019, 53, 447–458.

- Daniels, E.C.; Rodriguez, A.; Zabelina, D.L. Severity of misophonia symptoms is associated with worse cognitive control when exposed to misophonia trigger sounds. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227118.

- Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Anand, D.; McMahon, K.; Brout, J.; Kelley, L.; Rosenthal, M.Z. A preliminary investigation of the association between misophonia and symptoms of psychopathology and personality disorders. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3842.

- Taylor, S. Misophonia: A new mental disorder? Med. Hypotheses 2017, 103, 109–117.

- Møller, A.R. Misophonia, Phonophobia, and Exploding Head Syndrome. In Textbook of Tinnitus; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 25–27.

- Duddy, D.F.; Oeding, K.A.M. Misophonia: An Overview. Semin. Hear. 2014, 35, 84–91.

- Ferrer-Torres, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Confinement and the Hatred of Sound in Times of COVID-19: A Molotov Cocktail for People with Misophonia. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 663.

- Potgieter, I.; MacDonald, C.; Partridge, L.; Cima, R.; Sheldrake, J.; Hoare, D.J. Misophonia: A scoping review of research. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 75, 203–1218.

- Naylor, J.; Caimino, C.; Scutt, P.; Hoare, D.J.; Baguley, D.M. The Prevalence and Severity of Misophonia in a UK Undergraduate Medical Student Population and Validation of the Amsterdam Misophonia Scale. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 92, 609–619.

- Guetta, R.E.; Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Trumbull, J.; Anand, D.; Rosenthal, M.Z. Examining emotional functioning in misophonia: The role of affective instability and difficulties with emotion regulation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263230.

- Swedo, S.E.; Baguley, D.M.; Denys, D.; Dixon, L.J.; Erfanian, M.; Fioretti, A.; Jastreboff, P.J.; Kumar, S.; Rosenthal, M.Z.; Rouw, R.; et al. Consensus Definition of Misophonia: A Delphi Study. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 224, 841816.

- Jastreboff, M.M.; Jastreboff, P.J. Components of decreased sound tolerance: Hyperacusis, misophonia, phonophobia. ITHS News Lett. 2001, 2, 1–5.

- Ferrer-Torres, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Sounds of Silence in Times of COVID-19: Distress and Loss of Cardiac Coherence in People with Misophonia Caused by Real, Imagined or Evoked Triggering Sounds. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 638949.

- Schröder, A.; Vulink, N.; Denys, D. Misophonia: Diagnostic Criteria for a New Psychiatric Disorder. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54706.

- Bernstein, R.E.; Angell, K.L.; Dehle, C.M. A brief course of cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of misophonia: A case example. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2013, 6, E16.

- Sanchez, T.G.; Da Silva, F.E. Familial misophonia or selective sound sensitivity syndrome: Evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance? Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 84, 553–559.

- Palumbo, D.B.; Alsalman, O.; De Ridder, D.; Song, J.-J.; Vanneste, S. Misophonia and Potential Underlying Mechanisms: A Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 953.

- Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Anand, D.; McMahon, K.; Guetta, R.; Trumbull, J.; Kelley, L.; Rosenthal, M.Z. The mediating role of emotion regulation within the relationship between neuroticism and misophonia: A preliminary investigation. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 847.

- Hansen, H.A.; Leber, A.B.; Saygin, Z.M. What sound sources trigger misophonia? Not just chewing and breathing. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 2609–2625.

- Jastreboff, P.J.; Jastreboff, M.M. Tinnitus retraining therapy: A different view on tinnitus. ORL J. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Its Relat. Spec. 2006, 68, 23–29.

- Cavanna, A.E.; Seri, S. Misophonia: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2117–2123.

- Dozier, T.H.; Lopez, M.; Pearson, C. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Misophonia: A Multisensory Conditioned Aversive Reflex Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1975.

- Vitoratou, S.; Uglik-Marucha, N.; Hayes, C.; Erfanian, M.; Pearson, O.; Gregory, J. Item Response Theory Investigation of Misophonia Auditory Triggers. Audiol. Res. 2021, 11, 51.

- Zhou, X.; Wu, M.S.; Storch, E.A. Misophonia symptoms among Chinese university students: Incidence, associated impairment, and clinical correlates. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2017, 14, 7–12.

- Schwartz, P.; Leyendecker, J.; Conlon, M. Hyperacusis and misophonia: The lesser-known siblings of tinnitus. Minn. Med. 2011, 94, 42–43.

- McGeoch, P.D.; Rouw, R. How everyday sounds can trigger strong emotions: ASMR, misophonia and the feeling of wellbeing. BioEssays 2020, 42, 2000099.

- Webb, J. β-Blockers for the Treatment of Misophonia and Misokinesia. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 45, 13–14.

- Quek, T.; Ho, C.; Choo, C.; Nguyen, L.; Tran, B.; Ho, R. Misophonia in Singaporean Psychiatric Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1410.

- Dozier, T.H. Etiology, composition, development and maintenance of misophonia: A conditioned aversive reflex disorder. Psychol. Thought 2015, 8, 114–129.

- Tunç, S.; Başbuğ, H.S. An extreme physical reaction in misophonia: Stop smacking your mouth. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 416–418.

- Vidal, C.; Vidal, L.M.; Lage, M. Misophonia: Case report. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, 644.

- Kılıç, C.; Öz, G.; Avanoğlu, K.B.; Aksoy, S. The prevalence and characteristics of misophonia in Ankara, Turkey: Population-based study. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e144.

- Schröder, A.; Vulink, N.; Van Loon, A.J.; Denys, D. Cognitive behavioral therapy is effective in misophonia: An open trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 217, 289–294.

- Rouw, R.; Erfanian, M. A Large-Scale Study of Misophonia. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 453–479.