Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The mission of natural heritage conservation through different modalities has its main instrument in the creation and management of protected natural areas (PNAs) based on a conservation culture of natural ecosystems and sustainable development. Protected areas are well received throughout the world as environmental policy tools characterized by the preservation and protection of diverse ecosystems, where the original environment has not been essentially altered, producing a series of increasingly valued environmental services.

- biodiversity

- conservation

- protected natural areas

- human communities

- climate change

1. Introduction

The mission of natural heritage conservation through different modalities has its main instrument in the creation and management of protected natural areas (PNAs) based on a conservation culture of natural ecosystems and sustainable development [1]. Protected areas are well received throughout the world as environmental policy tools characterized by the preservation and protection of diverse ecosystems, where the original environment has not been essentially altered, producing a series of increasingly valued environmental services [2].

Academic, social, and legislative systems are conscious of their obligation to protect natural spaces, as well as the systems and cycles that are completely dependent on natural resources and that have supported life throughout millions of years of evolution [3][4].

The potential for economic, social, and political wellbeing that a PNA offers depends on the strategies implemented for natural biodiversity management and conservation [5].

2. The History of Biodiversity Conservation

In the current context of climate change and the post-COVID-19 pandemic, people in the developed world are looking anew at rural environments and natural ecosystems where human societies have had an historically balanced long-term relationship with nature. Populations trapped in crowded cities are showing more interest in nature, not just looking for beautiful landscapes but also places where they can escape to on holidays. As a result of this worldwide crisis, the idea of having a better quality of life, even urban life, through the conservation of natural ecosystems and nature-based solutions has become common [4][6].

Media coverage now favors this viewpoint of better life quality. For example, people now value the need for healthy food, organic cosmetics, space for leisure, clothes, and furniture made from ethically produced materials. Nowadays, sustainable consumption practices are becoming trendy in everyday urban life, if not common. For instance, regional suppliers, local markets, organic farms, sustainable fisheries, urban gardens, and allotments are examples of new ways to fulfill desires and return to harmony with nature in a more rational way of living [7].

Additionally, a renewed interest in the natural world is growing. Apart from the obvious and now more frequent catastrophic climate events (fires, droughts, heavy rains, and floods), the perception is that society is equally interested in topics such as pollinator decline, ocean pollution, and air quality. Specialized conservationists have had a particular resonance with the public, such as Carl Safina, whose books are global best-sellers.

Where is all this public interest coming from? Ecological studies and conservation efforts are not new. As early as 1869, the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace wrote in his book The Malay Archipelago about the value of biodiversity itself. He noticed the perfect equilibrium of the species on the islands and reflected on how their beauty is wasted in the “dark and gloomy woods, with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness, but when “civilized man” reaches the islands, he will certainly upset the balance of nature and make the birds extinct” [8] (p. 486).

The tradition of setting aside wilderness –its beauty and equilibrium, away from human actions–was the ideal of American conservationist pioneers, Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and Aldo Leopold. However, the idea of preserving landscapes, flora, and fauna alone developed into one of conservation in conjunction with human activities in the 20th century [9].

More than half a century ago, the science of conservation biology started in 1985 when a group of researchers met in La Jolla, San Diego, CA, USA, concerned about increased loss of species and the accelerated reduction in tropical forest [10]. The term biodiversity first appeared at the National Forum on Biodiversity held by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and Smithsonian Institute in September 1986. The focus of the forum was habitat destruction and species extinction, and the results were published with the title Biodiversity [11]. The concept of biodiversity, or biological diversity, relates to evolutionary biology and ecology. The key elements are individual species, but biodiversity also considers the role of the evolutionary process in species emergence and extinction, the causes of biodiversity loss, habitat destruction, invasive species, pollution, and overexploitation. In the Rio Convention, the definition of biological diversity covered three levels: species diversity, genetic diversity, and ecosystem diversity [12], but what ways have been found to preserve biodiversity whilst sharing the same space?

The Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project demonstrated that to maintain species diversity, the variety of habitats was more important than the size of an area [13]. For that reason, the importance of the protected areas was clearly to be big enough and with sufficient habitat diversity suitable for keystone species. These type of species are those that maintain ecosystem cohesion over time and ensure population viability [14].

MacArthur and Wilson [15] developed the theory of island biogeography and Simberloff and Abele [16] used it to propose that creating several small but connected NPAs could eventually contain and preserve more species than a bigger but more isolated reserve. Shaffer [17] developed the concept of minimum viable population; meanwhile, Newmar [18] demonstrated that in fragmented isolated habitats, small populations became extinct more quickly. All these elements together were used as key tools in designing wildlife reserves capable of maintaining and preserving biodiversity.

Nevertheless, and despite the creation of natural protected areas, numerous conferences, meetings, and thousands of published articles on the importance of biodiversity conservation remained confined to the academic world. Even broad political efforts, such as the United Nations Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro [12] or the Paris Agreement [19], seemed to hold little interest for the public.

Because lifestyle is now in danger, as early as 2007, George Beals Schaller pointed out that conservation problems are also social and economic as well as scientific, since humans benefit from wildlife [20]. In order to assign an intrinsic value to biodiversity, one looks at services that can be obtained from it. Ecosystem services have been defined as the conditions and processes through which natural ecosystems sustain and fulfill human life [21]. The services that species of microorganisms, animals, and plants provide and that are required to sustain human life are uncountable. The systems and natural cycles are product of billions of years of evolution. Whether humans appreciate it or not, all living beings depend entirely on ecosystems because both knowledge and ability are required to substitute them. For millennia, ecosystem services have been almost unnoticed, because they were not disrupted, although nowadays few places on Earth remain untouched (chemically, physically, or biologically). However, society likely values ecosystem services more as human impacts on the environment intensify, and the cost and limits of technological substitution (when possible) become more difficult or expensive [21].

Because humans have evolved and lived embedded in nature until recent times, the relationship between biophysical and sociocultural components of the ecosystems are historically interdependent, and a biocultural approach is now recognized as critical in conservation and restoration projects [22]. In fact, 11 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations are directly related to biodiversity conservation [23][24].

Since the mid-20th century, society has found that an effective method to improve biodiversity conservation is to involve local communities in the government of protected natural areas [9], which could either be by collaborative management (helping authorities) or co-management (jointly with authorities) [25]. Both methods incorporate traditional knowledge and current necessities of the inhabitants and can lead to more long-term, sustainable results. Collaborative governance is a way to eliminate imbalance between strong governmental politics and weak communities who live closely with wildlife. At the end, life quality improves both local communities and society [26][27][28].

Unfortunately, the richest countries in biodiversity are not always the most developed; for that reason, in 2014, the Nagoya Protocol, signed by many countries, established a global policy to improve biodiversity conservation, including sharing the benefits arising from using genetic resources fairly and equitably. Despite being signatories, many governments, companies, and institutions still do not adhere to the treaty. They still retain numerous patents, plant breeder rights, genetic resources, and plant varieties. However, the international community is trying to correct that and working to ensure that the profits of any natural exploitation or genetic resources stay in each nation. On top of that, in the current post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), the Aichi Targets about biodiversity loss have not been met, so society and researchers must work together to achieve them [28][29][30][31].

In the last two decades, involving people in biodiversity conservation through a process called citizen science has become a powerful tool. In this process, the public is involved in scientific projects in different ways. The easiest and most common one is to ask lay people for their help in gathering data for scientific projects following a specific protocol. In other cases, nonscientists can be engaged in the process of decision-making about policy issues that have technical or scientific components; alternatively, the scientific community becomes part of the policy decision-making process [32]. These projects are sometimes global, involving people from every continent, such as the example below about pollination [33]: (https://www.beeproject.science/croppollination.html, accessed on 10 April 2022).

This project was created to compile crop pollination data from published studies across the world and help predict pollination services. It also permits sharing data since the database has open access online, so scientists and institutions that want to contribute to new pollination datasets can add them easily.

In conclusion, a renewed desire (or necessity) is perceived to reinforce the reciprocal relationship with nature, and return to traditional crop methods instead of industrialized agriculture, small farms instead of macro livestock production, fields free of chemicals instead of insecticides, rational logging instead of deforestation, and a biocultural approach to restoration [34]. All these practices are perfect on a small scale, but none of them are possible on a major scale if consumption habits do not change. The amount of energy and resources and ecological cost of crowded urban societies have become unsustainable and new models, energies, productive forms, and imaginative solutions for waste and recycling are imperative.

3. Protected Natural Areas

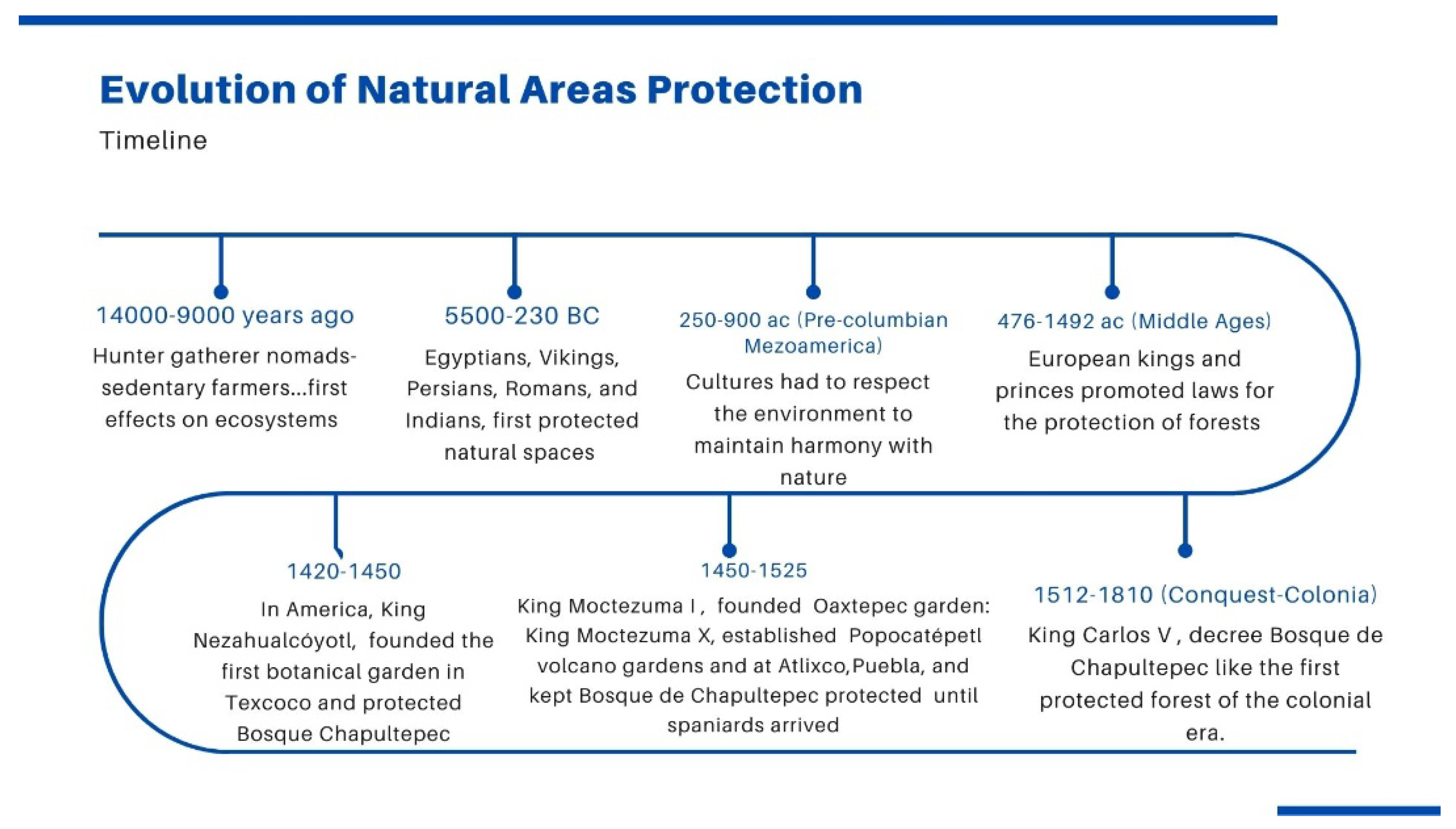

In the evolution of humanity, the passage from nomadic hunter-gatherers to sedentary farmers has had significant effects on ecosystems and the environment. These changes were caused by tree felling and forest clearing, using wood for construction and as fuel, competing for land and water, and evicting and consuming wild animals in the same area [35]. At the same time, some plants and animals were intensively exploited, which led to the appearance of the first domesticated species [36][37].

However, ancient cultures, such as Egyptians, Vikings, Persians, Romans, and Indians, have protected natural spaces for several centuries.

In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and in almost every ancient culture, people worshiped the sun, stars, moon, Earth, water, many animals, and almost all vegetation. All these elements of nature were conceived as divine, and cultures expressed their own realities linked to a cosmogony of which they were part and had to respect to maintain harmony with nature [38].

Incas used agricultural techniques, such as the construction of platforms or terraces to avoid soil erosion and take advantage of the slopes and hills [39]. Mayans linked their development with the tropical forest, basing their agricultural, horticultural, and forestry practices on protected pluriculturalism, called Pet-koot (round fence) [40].

In Mexico in the 15th century, the Mexica King Nezahualcóyotl established the first botanical garden in Texcotzingo, prohibiting hunting and imposing limits on obtaining firewood to protect the forests of his dominions in Texcoco. In 1428, he fenced the Chapultepec forest, enriched flora, planted the famous ahuehuete trees, and implanted a rich fauna, thus initiating its protection [41].

In 1450, Moctezuma Ilhuicamina established the Oaxtepec Garden, and in 1465, he took over Bosque de Chapultepec, a tradition that was followed by his successors. Moctezuma Xocoyotzin established gardens at the hillsides of Popocatépetl volcano and Atlixco in Puebla and maintained the one in Oaxtepec, Morelos, which had been operating as a protected area for more than 75 years when the Spaniards arrived [42].

During the Middle Ages, royalty promoted laws for forests and wildlife protection. Nevertheless, after the emergence of industrial cities in the mid-1700s, the exploitation of mineral coal polluted waters, soil, and atmosphere, which had an impact on policies and actions for the conservation of natural areas [38].

When Europeans discovered North America in the 15th and 16th centuries, they found it populated by diverse groups of indigenous people who showed a deep respect for the land and animals. This continent had abundant and seemingly inexhaustible stocks of wood, fertile soil, wildlife, fresh water, minerals, and other resources, so the colonizers felt that it should be conquered, opened, disassembled, and used as quickly as possible [43][44].

During the conquest and colonization by the Spaniards, the demand for construction materials and fuels increased, paying for forest clearance and making alterations to ecosystems. To stop such deforestation, King Carlos V of Spain decreed in 1530 that Bosque de Chapultepec and the hill surrounding it be owned by the City of Mexico, making this area the first protected forest of the colonial era.

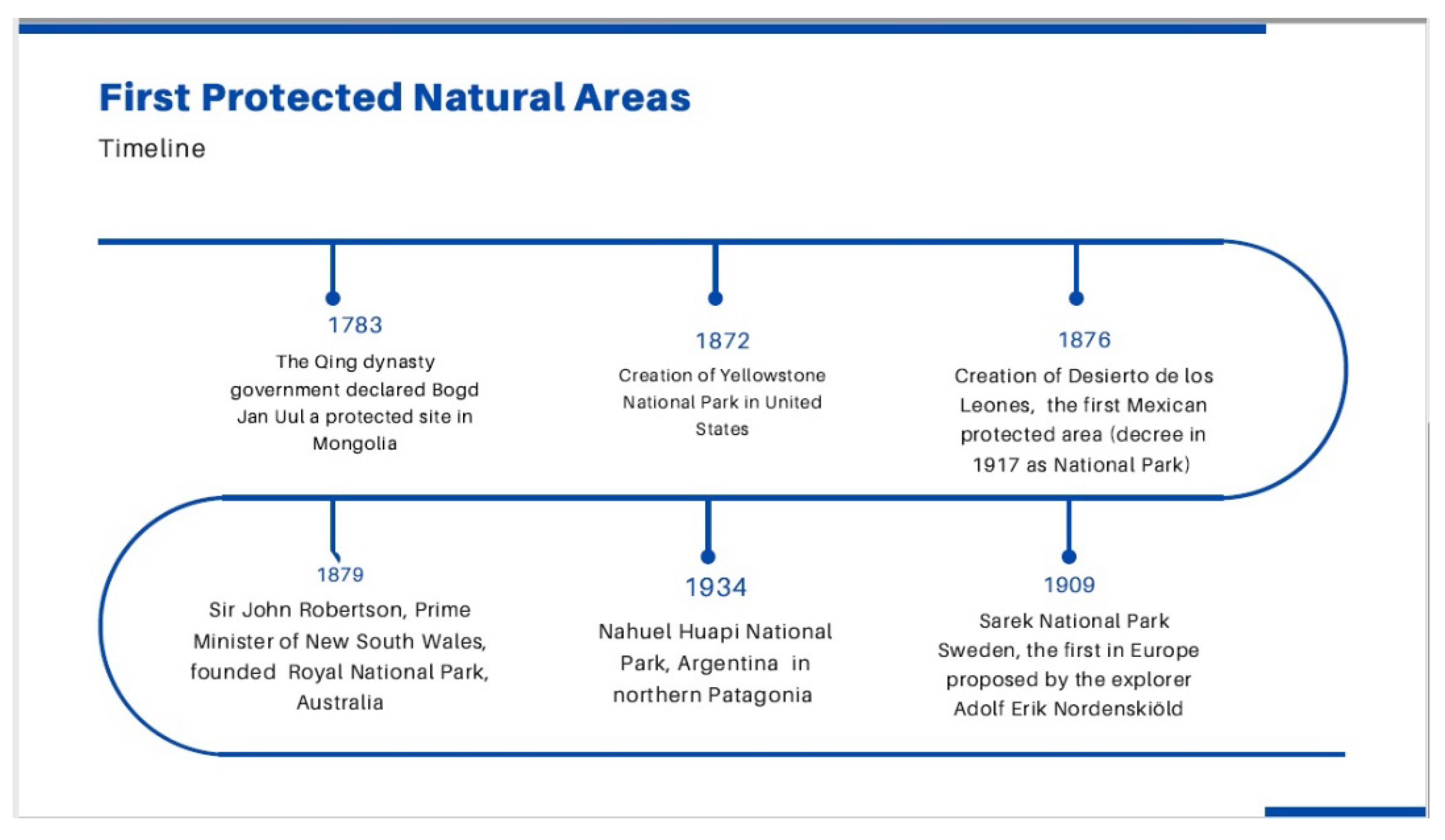

Throughout the expansion of Europeans in North America from 1607 to 1832, forests and wildlife were degraded and depleted at an alarming rate, so the task of protecting was passed down to subsequent generations. However, in the United States, federal action on the conservation of forest resources and wildlife did not properly begin until 1872 with the creation of Yellowstone National Park [44][45]. In the same decade, “Desierto de los Leones” was the first Mexican protected area, created in 1876 with the purpose of protecting the springs that supplied water to Mexico City, and decreed in 1917 as a national park [46]. These parks were the first of their kind in North America and set a precedent for preservation of biodiversity and cultural history (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Timeline of the evolution of Natural Protected Areas until the 20th Century.

The definition of a protected area for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is “a clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated, and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values” [47]. Although Yellowstone has been recognized as the first national park in the world, it was not the first protected natural area by a government. The oldest national parks on each continent have their own stories of origin and are home to evidence the world’s complex and changing relationship to public conservation [48]. Some examples of protected areas worldwide are described below, with a timeline of the first PNAs summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Timeline of some of the first Protected Natural Areas.

4. Human Communities in Protected Natural Areas

Traditionally, the communities that have lived within protected natural areas or in their area of influence depend on the use of available natural resources and this condition defines the characteristics of the population [49]. The study of human communities in PNAs has expanded into more than just the interaction of nature and society. From a sociological perspective, all these interactions become models that integrate social and natural systems for better human development through sustainable and environmental management, conservation, and governance, among other disciplines [50][51].

Thus, Salas-Zapata et al. [52] assume that social (culture, society, economy, and politics) and ecological systems converge in such a way that they interact, couple, dominate, and cause impacts and disturbances among them. This section shows some examples of the interactions between both kinds of systems grouped in different interacting categories: coupled, one dominating the other, or mutual disturbance.

Parathian [53] studied the impact-based conservation of two communities of Tikuna in the Colombian Amazon. Those communities have adopted some transcultural beliefs and shown innovation and resilience, which allowed them to cope with climate and environmental change and generate conservation processes and initiatives that influence local livelihoods; the study concluded that indigenous populations are malleable groups with a practical understanding and vital dynamics for identifying solutions to socio-ecological problems.

In other cases, community perception is an important way of evaluating conservation performance. In this case, the community members work on projects for effective biodiversity protection and the wellbeing of the people who live within or near protected areas. For instance, in Tarangire National Park in Tanzania and in Mole National Park in Ghana, watching wildlife and enjoying nature tourism not only have a positive impact on livelihoods and community development, and especially in governance matters, but also on national and international tourism [54].

Natural and human systems sometimes do not seem to influence each other. Harris et al. [55] studied interactions and links among users and mammals that inhabit a protected area, for example, direct (poaching) and indirect (domestic animals) human activities to the fauna of the largest complex of protected areas in West Africa (W-Arly-Pendjari). They found that although human pressure is dominant, it did not influence species richness or composition, which led them to label it a coupled human-dynamic system.

In other cases, forcing regulations in protected natural areas are necessary as a strategy for biodiversity protection. A study from Adamik and Berros [56] analyzed one of such situations on the Argentine coast (Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, Corrientes, and Misiones). In the case of Santa Fe and Misiones, the authors indicate that there is a sustainable exploitation of natural resources based on existing regulations. Although the legislation allows for the creation of PNAs in the four territories, their classification and specific treatment result on different management categories. However, these authors warn that in territories where few protected areas exist, natural environments are underrepresented. On the contrary, where many protected areas are established, precarious control by the authorities is observed, which causes impacts and disturbances.

In another example Olmos-Martínez et al. [49] studied the effect of implementing a protected natural area on the wellbeing of rural communities in Baja California Sur, México. In this case, although the creation of the protected area has hampered access to natural resources, it has also increased the sense of wellbeing of the population based on social and economic indicators in the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve.

Karanth et al. [57] carried out a study on voluntary community resettlements of the protected areas of India. The authors studied the strategy of people exclusion to minimize the anthropogenic threats of wildlife. The project is challenging for the government since an estimated 4.3 million people share spaces with megafauna within protected areas, indicating that resettlement policies focus on paying in cash or a compensation package for land for families relocating voluntarily. These authors also found that 89% wanted to move to get better education, health care, roads, less human conflict, and better wildlife; thus, households that depend on wage labor decided to move and smallholders looked for better opportunities in agriculture.

In addition, research on the analysis of conservation policies in urban contexts leads to challenges faced by decision makers and society in general. In that sense De la Mora [58] shows two convergent conservation policies in Mexico, which are about Environmental Services and PNAs as instruments of public policy and the interactions from their implementation for the conservation of urban socio-ecosystems. The author alluded that urban and peri-urban PNAs should enjoy greater political visibility in urban and environmental decision-making territorial processes for their permanence. Thus, the conservation policy of environmental services can lead to the social and political reassessment of their strategic importance, which would contribute to urban planning (housing, hydraulic sector, forest areas, among others).

On the other hand, Mutanga et al. [59] conducted a study on community perception of wildlife conservation and tourism in adjacent communities within four protected areas in Zimbabwe. These authors found that one community had neutral perceptions on wildlife conservation, but the other three had positive perceptions on the same issue. However, all four communities had negative tourism perceptions because they have not been involved, and natural resource benefits are not shared fairly among stakeholders.

Related to the above, Olmos-Martínez et al. [60] alluded to this situation in their study on anthropogenic pressure in the PNA Archipelago Espíritu Santo, in Baja California Sur, Mexico. The authors concluded that tourism exerts greater pressure than other activities, such as fishing, because of its high demand and growing activity. Although the type of tourism practiced is eco- and adventure tourism, their activities produce pollution, flora and fauna alteration, exotic species introduction, and fishing sector problems.

However, Olmos-Martínez et al. [61] found a successful case related to the use of natural resources and ecotourism in the PNA “Tortuguero El Verde Camacho” sanctuary, in Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Based on the collaboration between the society, the government, and the organization within an ecotourism cooperative society, the community has generated socioeconomic development that bolsters ecotourism services with an emphasis on the conservation, preservation, and management of the coastal wetland and endangered species, such as the olive ridley turtle. In addition, tourism in Mexico is established as a permitted activity in the PNA management program since it allows raising awareness of biodiversity protection, which also represents an economic alternative that benefits local communities and users [3].

Some studies of PNAs are related to evaluating vulnerability as a management element; this is the case in the analysis by Verdugo et al. [62], which calculated the environmental vulnerability of the marine part of Bahía de Loreto National Park in Baja California Sur, Mexico, based on environmental indicators using the exposure-sensitivity-capacity method. Their results show that the greatest vulnerability is found in the coastal zone in front of the Peninsula and in Isla del Carmen where ecotourism is practiced, as well as in Isla Catarina due to the pressure from fisheries and, therefore, interactions in social and ecological systems.

Andrade and Rhodes [63] mention that PNA management, in some cases, fully integrates important factors, such as social, cultural, and political factors. However, they have caused adverse social impacts in some cases on local communities that altered their traditional ways of life, limited their control and access to natural resources, and generated conflicts between administrators and local communities. The authors analyzed the key factors that lead to better compliance with conservation strategies and observed that local community participation is the only variable that reacted significantly with the level of compliance with the PNA policies—the greater the participation is, the greater the compliance is.

In addition to the above and because tourism has a social representation approach, this activity allows for the inclusion of interactions, history, and culture. Sarr et al. [64] reviewed these interactions in La Langue de Barbarie National Park in Northern Senegal. Members of the community found evidence of the failure of tourism programs and projects with community participation given the perception of the same communities, which implies division in groups with different interests, to such a degree that inhabitants consider emigration from the site.

Likewise, Olaniyi, et al. [65] state that biological diversity in Nigeria is highly degraded and far from the Sustainable Development Goals. This situation leads to a major problem since PNAs constitute the food base for survival of the host communities in that area. Thus, the authors propose community participation policies to improve rural livelihoods.

In addition, Fay [66] studied the process of merging Dwesa-Cwebe Nature Reserves with Pafuri Triangle reserves in South Africa. This author addresses that since PNA joint management has emerged, the communities have been involved in formal negotiations with government officials and groups of non-governmental organizations in search of mutual benefit. However, they have found that mutual gains and distributive approach have reduced the power of communities in decision-making.

Finally, Olmos-Martínez et al. [19] studied the perception of the population living in the PNAs of Baja California Sur, Mexico on climate change (CC) and environmental changes in the area where they live. The study was carried out from different topics (environment, coastal areas, soil, water, society, fishing, agriculture, livestock, and tourism). The results indicated that the local population has empirical knowledge about the effects of climate change, both economically and socially. This knowledge is a tool for decision makers that allows recognizing human behavior in social, economic, and environmental changes that may contribute to mitigation and adaptation strategies in facing the phenomenon.

In summary, human communities have a dynamic and adaptive relationship with nature within PNAs. Beyond being an instrument of environmental policy, PNA management, in some cases, fully integrates important social, cultural, and political factors.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/d14060441

References

- Guerrero, E. México. El Paraíso de Los Pinos, Robles y Cactus. In Las Áreas Protegidas de América Latina: Situación Actual y Perspectivas Para el Futuro; Elbers, J., Ed.; UICN: Quito, Ecuador, 2011; pp. 69–78.

- Olmos-Martínez, E.; González-Ávila, M.E.; Contreras-Loera, M.R. Percepción de La Población Frente Al Cambio Climático En Áreas Naturales Protegidas de Baja California Sur, México. Polis Rev. Latinoam. 2013, 12, 459–481.

- Arizpe, O.; Olmos-Martínez, E.; Ibáñez, R.M.; Armenta Martínez, L.F. Áreas Naturales Protegidas y Turismo Sustentable En Baja California Sur. In Turismo, Desarrollo Económico y Sustentabilidad en Baja California Sur; Juárez Mancilla, J., Cruz Chávez, P.R., Torres García, A.F., Cruz Chávez, G.R., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa: Culiacan, Mexico, 2018.

- Acreman, M.; Smith, A.; Charters, L.; Tickner, D.; Opperman, J.; Acreman, S.; Edwards, F.; Sayers, P.; Chivava, F. Evidence for the Effectiveness of Nature-Based Solutions to Water Issues in Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 063007.

- Rascón Palacio, E. Áreas Protegidas: Aproximación A Su Proyección Socio-Económica Y Política En Centroamérica. Delos Desarro. Local Sosten. 2010, 3, 13.

- Herrmann-pillath, C.; Hiedanpää, J.; Soini, K. The Co-Evolutionary Approach to Nature-Based Solutions: A Conceptual Framework. Nat.-Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100011.

- Cárdenas, M.L.; Wilde, V.; Hagen-Zanker, A.; Seifert-Dähnn, I.; Hutchins, M.G.; Loiselle, S. The Circular Benefits of Participation in Nature-Based Solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4344.

- Wallace, A.R. Archipiélago Malayo; Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, Cien del Mundo: Mexico City, Mexico, 1869.

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571.

- Soulé, M.E. (Ed.) Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1986.

- Wilson, E.O. (Ed.) Biodiversity; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1988.

- Cooper, H.D.; Noonan-Mooney, K. Convention on Biological Diversity. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 2nd ed.; Levin, S.A., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2013; pp. 306–319.

- Bierregaard, R.O.; Gascon, C.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Mesquita, R. (Eds.) Lessons from Amazonia: The Ecology and Conservation of a Fragmented Forest; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2001.

- Soulé, M.E.; Simberloff, D. What Do Genetics and Ecology Tell Us about the Design of Nature Reserves? Biol. Conserv. 1986, 35, 19–40.

- Macarthur, R.H.; Wilson, E.O. The Theory of Island Biogeography; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1967.

- Simberloff, D.S.; Abele, L.G. Island Biogeography Theory and Conservation Practice. Science 1976, 191, 285–286.

- Shaffer, M.L. Minimum Population Sizes for Species Conservation. Bioscience 1981, 31, 131–134.

- Newmark, W.D. A Land-Bridge Island Perspective on Mammalian Extinctions in Western North American Parks. Nature 1987, 325, 430–432.

- UNFCCC. Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Schaller, G.B. A Naturalist and Other Beasts: Tales from a Life in the Field; Sierra Club Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007.

- Daily, G. Introduction: What Are Ecosystem Services. In Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems; Daily, G., Ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA; Covelo, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 1–10.

- Chang, K.; Winter, K.B.; Lincoln, N.K. Hawai’i in Focus: Navigating Pathways in Global Biocultural Leadership. Sustainability 2019, 11, 283.

- Opoku, A. Biodiversity and the Built Environment: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 1–7.

- UNDP. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G. Collaborative Management of Protected Areas: Tailoring the Approach to the Context; Issues in Social Policy; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1996.

- Ullah, I.; Kim, D.Y. A Model of Collaborative Governance for Community-Based Trophy-Hunting Programs in Developing Countries. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 18, 145–160.

- Biodiversity Collaborative Group. Report of the Biodiversity Collaborative Group; Biodiversity (Land and Freshwater) Stakeholder Trust: Wellington, New Zeland, 2018.

- Xu, H.; Cao, Y.; Yu, D.; Cao, M.; He, Y.; Gill, M.; Pereira, H.M. Ensuring Effective Implementation of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Targets. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 411–418.

- Williams, B.A.; Watson, J.E.M.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Ward, M.; Brooks, T.M.; Butt, N.; Bolam, F.C.; Stuart, S.N.; Mair, L.; McGowan, P.J.K.; et al. A Robust Goal Is Needed for Species in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Conserv. Lett. 2020, 14, e12778.

- Nicholson, E.; Watermeyer, K.E.; Rowland, J.A.; Sato, C.F.; Stevenson, S.L.; Andrade, A.; Brooks, T.M.; Burgess, N.D.; Cheng, S.T.; Grantham, H.S.; et al. Scientific Foundations for an Ecosystem Goal, Milestones and Indicators for the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 1338–1349.

- Nature. Biodiversity Faces Its Make-or-Break Year. Nature 2022, 601, 1.

- Nunes, N.; Björner, E.; Hilding-Hamann, K.E. Guidelines for Citizen Engagement and the Co-Creation of Nature-Based Solutions: Living Knowledge in the URBiNAT Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13378.

- Beeproject.Science. Available online: https://www.beeproject.science/croppollination.html (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Winter, K.B.; Ticktin, T.; Quazi, S.A. Biocultural Restoration in Hawaiʻi Also Achieves Core Conservation Goals. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 18.

- Ibañez, J.J.; Muñiz, J. De Cazadores Recolectores Nómadas a Agricultores y Ganaderos Sedentarios. Available online: https://fundacionpalarq.com/de-cazadores-recolectores-nomadas-a-agricultores-y-ganaderos-sedentarios/ (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Ahmad, H.I.; Ahmad, M.J.; Jabbir, F.; Ahmar, S.; Ahmad, N.; Elokil, A.A.; Chen, J. The Domestication Makeup: Evolution, Survival, and Challenges. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 103.

- Groß, D.; Piezonka, H.; Corradini, E.; Schmölcke, U.; Zanon, M.; Dörfler, W.; Dreibrodt, S.; Feeser, I.; Krüger, S.; Lübke, H.; et al. Adaptations and Transformations of Hunter-Gatherers in Forest Environments: New Archaeological and Anthropological Insights. Holocene 2019, 29, 1531–1544.

- Luminet, J.-P. Creation, Chaos, Time: From Myth to Modern Cosmology. Cosmology 2016, 24, 501–515.

- Meghji, S. The Innovative Technology That Powered the Inca; BBC: London, UK, 2021.

- De la Maza Elvira, R. Una Historia de Las Áreas Naturales Protegidas En México. Gac. Ecol. 1995, 51, 15–68.

- Givens, H. Nezahualcoyotl: History and Historiography. 2014. Available online: https://hannahgivens.wordpress.com/2014/05/23/nezahualcoyotl-history-and-historiography/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Berdan, F.F. The Aztecs. Lost Civilizations, 1st ed.; Reaktion Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2021.

- Castañeda, R.J. Las Áreas Naturales Protegidas de México: De Su Origen Precoz a Su Consolidación Tardía. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrón. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2006, 10, 1138–9788.

- Vásquez Sánchez, M.Á. Conservación de La Naturaleza y Áreas Naturales Protegidas En Territorios de Los Pueblos Originarios de La Frontera Sur de México. Soc. Ambient. 2017, 15, 117–130.

- Bahia de Aguiar, P.C.; dos Santos Moreau, A.M.S.; de Oliveira Fontes, E. Protected Natural Areas: A Brief History of the Emergence of National Parks and Extractive Reserves. Rev. Geogr. Am. Cent. 2013, 50, 195–213.

- Chavarría, Y.O.; Martínez García, A.L.; Ortíz, C.E.; Goyenechea, I. Evolución En La Selección de Áreas Protegidas En El Continente Americano: El Caso de Estados Unidos, México y Costa Rica. Boletín Científico del Inst. Cienc. Básicas e Ing. 2019, 7, 47–53.

- IUCN. International Union for Conservation of Nature and United Nations Environment Programme. “Protected Areas: About”. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/theme/protected-areas/about (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Sheail, J. Nature’s Spectacle, The World’s First National Parks and Protected Places, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2010.

- Olmos-Martínez, E.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, G.; Salas, S.; Ortega-Rubio, A. Efecto de La Implementación de Un Área Protegida Sobre El Bienestar de Comunidades Rurales de Baja California Sur. In Las Áreas Naturales Protegidas y la Investigación Científica en México. (pp. 249–282); Ortega–Rubio, A., Pinkus-Rendón, M.J., Espitia-Moreno, I.C., Eds.; Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S. C., La Paz, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Mérida, Yucatán y Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo: Morelia, Mexico, 2015; p. 572.

- Olmos-Martínez, E.; Ortega-Rubio, A. Socio-Ecological Studies in Natural Protected Areas. Linking Community Development and Conservation in Mexico. In Socio-Ecological Studies in Natural Protected Areas; Ortega-Rubio, A., Ed.; Springer: La Paz, Mexico, 2020; p. 625.

- Challenger, A.; Bocco, G.; Equihua, M.; Lazos Chavero, E.; Maass, M. La Aplicación Del Concepto Del Sistema Socioecológico: Alcances, Posibilidades y Limitaciones En La Gestión Ambiental de México. Investig. Ambient. Cienc. Política Pública 2014, 6, 1–21.

- Salas-Zapata, W.A.; Ríos-Osorio, L.A.; Álvarez-Del Castillo, J. Conceptual Bases for a Classification of Socioecological Systems in Sustainability Research. Rev. Lasallista Investig. 2011, 8, 136–142.

- Parathian, H. Understanding Cosmopolitan Communities in Protected Areas: A Case Study from the Colombian Amazon. Conserv. Soc. 2019, 17, 26–37.

- Abukari, H.; Mwalyosi, R.B. Local Communities’ Perceptions about the Impact of Protected Areas on Livelihoods and Community Development. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00909.

- Harris, N.C.; Mills, K.L.; Harissou, Y.; Hema, E.M.; Gnoumou, I.T.; VanZoeren, J.; Abdel-Nasser, Y.I.; Doamba, B. First Camera Survey in Burkina Faso and Niger Reveals Human Pressures on Mammal Communities within the Largest Protected Area Complex in West Africa. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12667.

- Adamik, S.; Berros, M.V. Áreas Naturales Protegidas En El Litoral Argentino: Un Análisis Comparativo De Las Regulaciones Vigentes. Derechos En Acción 2021, 19, 410–436.

- Karanth, K.K.; Kudalkar, S.; Jain, S. Re-Building Communities: Voluntary Resettlement from Protected Areas in India. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 183.

- Mora-De la Mora, G.D.L. Sociopolitical Approach for the Analysis of Conservation Policies in Urban Contexts: Between Environmental Services and Protected Natural Areas. Perf. Latinoam. 2019, 27, 53.

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Gandiwa, E.; Muboko, N. Community Perceptions of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism: A Case Study of Communities Adjacent to Four Protected Areas in Zimbabwe. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2015, 8, 564–582.

- Olmos-Martínez, E.; Arizpe, O.; Maldonado-Alcudia, C.; Roldán-Clarà, B. Conservation of Biodiversity vs Tourism and Fishing at the Archipelago Espiritu Santo in the Gulf of California. In Mexican Natural Resources Management and Biodiversity Conservation Recent Case Studies; Ortega-Rubio, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018.

- Olmos-Martínez, E.; Ibarra-Michel, J.P.; Velarde-Valdez, M. Socio-Ecological Effects of Government and Community Collaborative Work to Local Development in a Natural Protected Area. In Socio-Ecological Studies in Natural Protected Areas; Ortega-Rubio, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 511–535.

- Verdugo, M.D.; Arizpe-Covarrubias, O.; Olmos Martinez, E. Evaluación de La Vulnerabilidad Como Elemento de Manejo En Áreas Naturales Protegidas: Parque Nacional Bahía de Loreto, México. In Estudios Recientes Sobre Economía Ambiental y Agrícola en México; Hernández Trejo, V., Valdivia Alcalá, R., Cruz Chávez, P.R., Cruz Chávez, G.R., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo: La Paz, Mexico, 2019; pp. 325–344.

- Andrade, G.S.M.; Rhodes, J.R. Protected Areas and Local Communities: An Inevitable Partnership toward Successful Conservation Strategies? Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 17.

- Sarr, B.; González-Hernández, M.M.; Boza-Chirino, J.; de León, J. Understanding Communities’ Disaffection to Participate in Tourism in Protected Areas: A Social Representational Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3677.

- Olaniyi, O.E.; Akinsorotan, O.A.; Zakaria, M.; Martins, C.O.; Adebola, S.I.; Oyelowo, O.J. Taking the Edge off Host Communities’ Dependence on Protected Areas in Nigeria. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 269, 13.

- Fay, D.A. Mutual Gains and Distributive Ideologies in South Africa: Theorizing Negotiations between Communities and Protected Areas. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 35, 81–95.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!