Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Microbiology

Local wisdom practiced in the farming activities in West Timor is a response to the marginality of the dominant environment in semi-arid areas. Actions were taken, such as combining different plants or food crops in a parcel of land, have proven to be the best strategy to maintain a sufficient level of food production and, at the same time, maintain soil biology and fertility. Different legume crops, both in the upland and local agroforestry of Mamar, provide rich soil biology and sustain crop productivity.

- farming system, local-agroforestry, Mamar

- Trichoderma species

- Timor Island, semi-arid environment, mosaic environment

1. Soil Nutrient Retention and Its Availability

Climatologically, the western part of Timor Island, East Nusa Tenggara (ENT) province, Indonesia, is classified as a semi-arid area, with a limited amount of annual rainfall; the precipitation is less than 1500 mm/year, and there are only three to four wet months per year, namely, December to March/April [19]. This differs from the dominant wet tropical climate of the western part of Indonesia. Another feature is that most of the soils are young; they are characterized by a thin solum depth of <20 cm and a sloping land surface that is due to the topography, which is dominated by hills and mountains [20]. Topographic conditions show a positive correlation with soil moisture [21]. In terms of the soil fertility of West Timor, the soil reaction (pH) is alkaline, but there are still problems with the availability of nitrogen and phosphate and the low C-organic content of the soil. This condition is a challenge for agricultural production faced by local farmers and the government in the expansion of agricultural development programs. The consequence of this challenging situation is that without being supported by sound knowledge and cultivation technology, agricultural productivity is low, and there is at times no harvest.

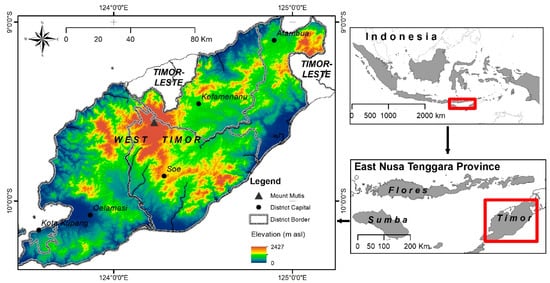

The altitude of West Timor is dominated by the lowland area of below 700 m above sea level (m asl), which covers 86% of the highland area above 700 m asl [19] (Figure 1). In terms of land development, West Timor is dominated by young soils, such as Entisols and Inceptisols, as well as more developed soils, such as Vertisols and Alfisols. These soils develop both from calcareous sediments and from deposit parent materials [20]. In the perspective of soil nutrient retention and nutrient availability, the values of soil chemical parameters are varied, but generally lie in the low to high category.

Figure 1. West Timor, based on elevation ranging from lowland to highland.

Regarding the presence of C-organic, it can be described that it almost varies between locations. In [22], the soils overgrown with Sandalwood (Santalum album L.) in the North Central Timor district contained 1.18% (low) and 4.39% (high) organic C-organic. Meanwhile, as reported by [23], from each type of Vertisol and Alfisol soil in the Kupang district, the C-organic values were 1.26 and 1.05% (low), respectively, including rice land in the Malaka district [24]. Similar conditions were also found in other locations in Kupang [25] in the medium category (2.85%) [26].

In terms of Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC), it is generally classified as medium to high, ranging from 19.84 to 31.67 cmol(+) kg−1 [25,27]. The existence of a good CEC value is closely related to the area that is dominated by clay type 2:1 montmorillonite [28]. The characteristics of nutrient retention, such as acidity (pH H2O), C-organic, and CEC, mentioned above, are not much different from the results observed at 16 locations in the agroforestry environment in West Timor.

2. Soil Biology in West Timor

Soil biology is one of the major soil properties that are often considered an indicator of soil health. Two important indicators commonly used to assess soil biology properties include soil organic carbon and soil microorganisms. Soil organic carbon (SOC) plays an important role in maintaining physical, chemical, and biological properties in the soil, and therefore, the SOC has been recognized as the single most significant soil health indicator [39,40,41]. Generally, soil organic carbon in West Timor ranges from low to moderate, but mostly, the SOC is low. The low content of SOC in West Timor is very likely related to the low rainfall in the region, which limits plant growth and the deposit of plant residues in the soil, and the hot weather, which favors the decomposition process of organic matter.

Beneficial soil microorganisms, in particular, are involved in many crucial processes in the soil and in the natural fertility of soil [42,43]. For example, a non-functional group of soil microorganisms, often called the decomposer, plays an important role in the mineralization process of organic matter, leading to the release of nutrients in the soil ready for plant uptake, and a functional group of soil microorganisms, which specialize in a certain function in the soil or for plant growth. Examples of these are free living and symbiotic N2-fixing bacteria, mycorrhizas, plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), and Trichoderma. These beneficial soil microorganisms are important in supporting plant growth in West Timor where the soil is commonly less fertile, and where water becomes a limiting factor for plant growth.

Few studies have been undertaken on the potential of beneficial soil microorganisms in West Timor. The genetic biodiversity of leguminous plants in West Timor, such as wild legumes or legumes, cultivated around the farm land for food or for forage, has been explored [44]. Regarding the low fertility of the soil in West Timor, the occurrence of these leguminous plants is very important due to their role in contributing nitrogen (N) to the soil through the activity of Rhizobium in the roots. The occurrence of ingenious beneficial microorganisms involved in N fixation has also been reported [45].

The presence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), the symbiotic mutualisms between the fungi and roots of higher plants [46], has been reported in the rhizosphere of many types of natural vegetation or plants in West Timor [6,47,48,49]. As the soils of West Timor are mostly calcareous and less fertile, the abundant indigenous mycorrhizal could become a biological natural supporting mechanism that could enhance plant growth in the region by improving plant nutrient absorption; most notably, phosphorus (P), which is highly adsorbed in calcareous soil. Moreover, mycorrhizal fungi are also known to improve plant resistance to drought [46]. This can help in the survival of plants under water stress commonly occurring on dryland in West Timor. Indigenous arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) were found to be more abundant in the traditional farming system, where farmers perform minimum tillage and avoid the use of inorganic fertilizer, than the modern agriculture system, which involves the use of inorganic fertilizer [6]. This finding suggests that the traditional farming system in West Timor favors the health of soil biology. The potential of indigenous AMF to improve the soil phosphorus (P) availability and growth of maize with a lower amount of inorganic P in the calcareous soil of West Timor has also been recently reported [26].

The potential of indigenous plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) has also been reported as a cost-effective and safe alternative approach to improve plant growth and developments, as they are able to produce plant-growth regulators, as well as enhance the soil condition and protection from soil pests and diseases [50]. In [51], it was found that indigenous Bacillus sp. and Pseudomonas sp. were capable of reducing brown rot gummosis disease in Soe Mandarin. Bacillus sp. has also been reported to produce indol acetic acid (IAA) and increase phosphorus solubility [52]. In [53], it was also found that local Bacillus spp. had the potential to control rice leaf spot disease caused by Drecschlera oryzae. Furthermore, this study also indicated that Bacillus spp. can also stimulate plant growth. The occurrence of other types of PGPR in West Timor included Gluconacetobacter sp. [54] and Acinetobacter sp., Enterobacter sp., Klebsiella sp., and Pantoea sp. [45].

Two other potential soil microorganisms that are also important in supporting plant growth in the semi-arid land of West Timor are Trichoderma and Streptomyces. Trichoderma was found to be ubiquitous in different plants in West Timor, such as mandarin, rice, maize, tomato, and chili. Trichoderma has been found to play a number of roles in agriculture, including promoting plant growth [55,56] and inducing resistance to plant pathogens [57,58,59]. Within the context of the West Timor dryland agro-ecosystem, indigenous Trichoderma was found to be able to restrict the growth of root and basal stem rot disease of soe mandarin caused by Phytophthora palmivora [60], and also to reduce the growth of Diplodia sp. in vitro [61]. In addition, indigenous Trichoderma species from West Timor were also found to suppress brown spot disease and increase the yield and yield-contributing characteristics of upland rice [62]. In a pot experiment conducted in [62], the local Trichoderma species propagated in corn rice bran were applied to the planting media before planting, while the fungicide was applied through spraying.

3. Farming and Soil Fertilization

Although there is various local wisdom practiced by farmers in West Timor, there is a counter-productive action, “the slash-and-burn system”, which is currently still carried out by local farmers before planting. Since no study has been undertaken on the impact of slash-and-burn on the soil microbiota in West Timor, this review was based on similar studies conducted elsewhere. The effect of fire on soil microbes has been reported with various results. For instance, in [67], it was found that in a long unburnt site (45 years) of the Eucalyptus marginata forest, ectomycorrhiza levels were higher than those of the site that had remained unburnt for 6 years and 1 month. Accordingly, fire could not only eliminate the substrate of certain ectomycorrhizas, but could also have a sterilizing effect that could reduce the inoculum potential of the fungal symbionts [67]. In contrast, other authors found that the exclusion of fire from the Eucalyptus forest resulted in an adverse impact on mycorrhizal association due to soil ecological changes [68,69]. The impact of burning on soil microorganisms may be related to the time of burning [70]. The study found that the abundance and diversity soil microorganisms decreased at 2 and 4 weeks after burning, respectively, but increased 6 weeks after burning. This suggested that if the soil is left undisturbed for a long time after burning, the soil, including its microorganisms, may recover [70]. However, the capability of soil microbiota to recover after burning might be different depending on the resistance of the soil microbes to high temperatures [70,71].

Slash-and-burn resulted in changes in soil chemical properties, including reducing soil acidity and increasing some base cations [72]. Following changes in the soil chemical properties due to slash-and-burn, there were also changes in some bacteria communities’ taxa and some functional bacteria, and these changes could be considered a buffer for drastic changes in soil fertility after slash-and-burn [73]. Changes in soil chemical properties, such as a decrease soil organic C and N, as well as changes in soil biology, such as soil respiration, microbial biomass C and enzyme activities due to prescribed burning, have also been reported [18]. Despite the improvement of some soil chemical factors, such base cations, pH, and CEC due to slash-and-burn, it is a fact that soil microbes are the components of soil biology that are most affected. Thus, in the future, minimizing the frequency and intensity of the burns may need to be considered for a more sustainable farming system in West Timor dryland.

In addition to the potential of indigenous beneficial soil microorganisms found in the soil of West Timor, there are also some traditional agricultural cultivating systems practiced by local farmers that can maintain the biological health of soil, including minimum or zero tillage, as well as the use of green manure, cow manure, and a mixed-cropping planting system of leguminous plants, such as peanut, mungbean, or pigeon pea, together with non-leguminous plants, such as maize, pumpkin, and/or Siamese pumpkin. Minimum tillage or zero tillage is a conservative way to maintain land sustainability, including soil biological health [74,75]. This practice has been undertaken by farmers for a long time as a local technique to maintain soil fertility [38,76,77].

4. Crop Diversity in Upland Farming

Crop diversity including food crops, vegetables, fruits, and estate crops in West Timor is high among crop types and varieties. Crops are cultivated by farmers in West Timor based on altitude and water availability, as stated in [80,81]. Additionally, the water availability determines crop types and rotation patterns in a given region [82,83]. Crops that are cultivated at high altitude (>700 m asl) are different from those grown at low to middle altitudes (0–<700 m asl). Similarly, crops cultivated on land that has permanent water sources are different from those on dryland without water sources.

Crops cultivated at high altitudes in West Timor, such as in North Molo and Fatumnasi Subdistricts in South Central Timor District, and also in West Miomafo of the North Central Timor District, include maize (Zea mays L.), sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.), potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), carrot (Daucus carota L.), kidney-bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), prey onions (Allium porrum Leek), coriander (Koriandrum sativum L.), snaps (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), garlic (Allium sativum L.), mandarin (Citrus reticulata L.), apple (Malus domestica L.), and coffee (Coffea arabica L.) [84]. Horticultural crops dominate in the highlands, and they are planted more by farmers to earn an income [85].

Crops cultivated on irrigated land at low to middle altitudes in West Timor include irrigated rice, maize, onion (Allium cepa L.), brassica (Brassica chinensis L.), chayote (Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw.), long beans (Vigna cylindrical L.), bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.), chili (Capsicum annum L.), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), melon (Cucumis melon L.), water melon (Citrullus lanatus L.), grape (Vitis vinifera L.), and mungbean (Phaseolus radiatus L.) [84]. Most of the vegetable crops are farmed after the main crop rice is harvested or during the dry season.

However, crops cultivated on dryland at low to middle altitudes include upland rice (Oryza sativa L.), maize (Zea mays L.), pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Durch), rice bean (Vigna umbelata Thunb), pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.), ground nut (Arachis hypogaea L.), mung bean (Vigna radiata), barley (Setaria italica L.), job’s tear (Coix lacrima-jobi L.), sorgum (Sorghum bicolor L.), banana (Musa sp.), coconut (Cocos nucifera L.), mango (Mangifera indica L.), betel nut (Areca catechu L.), betel (Piper betle L.), salaka (Salacca zalacca L.) cassava (Manihot utilissima Pohl), and cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale L.). The crop diversity determines the soil fertility and farm sustainability in a given region. Cultivating various crops in a parcel of land, on the one hand, requires different nutrients from the soil, while on the other hand, provides a low crop failure risk.

Polyculture farming is considered local Timorese knowledge, and it involves farming or planting crops that have economic, social, and ecological benefits. Farmers in some villages of the Mutis highland deal with cultivated horticultural crops, such as onion (Allium cepa), garlic (Allium sativum), potato (Solanum tuberosum), chili (Capsicum annuum), maize (Zea mays), groundnut (Arachis hypogaea), cassava (Manihot esculenta), and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas). Some farmers’ groups cultivate some herbs and medicinal plants, such as ginger (Zingiber officinale), galangal (Alpinia galanga), aromatic ginger (Kaempferia galanga), turmeric (Curcuma longa), and Curcuma (Curcuma zanthorrhiza) [5,9].

Farmers simply let plants or vegetation grow naturally in the gardens of their homes and on upland farms, such as nutmeg (Myristica sp.); the ficus tree (Ficus sp.); the small cotton tree (Bombax malabarica); white-barked Acacia (Acacia leucophloea); the lac tree (Scheilechera oleosa); the betel nut palm (Areca catechu); albizia (Albizia chinensis); the helicopter tree (Gyrocarpus americanus); as well as trees for bees: Wenlandia buberkilli var. Timorensis, Todalia asiabeca, and Albizzia saponaria [9]. They also plant or sell wooden vegetations for building materials, such as mahogany trees (Swietenia machrophylla King, Swietenia mahagony L. Jacg.), white teak (Gmelina arborea (Burm F.) Merr), teak (Tectona grandis L.), suren toon/iron redwood (Toona sureni (Blume) Merr), Timoo wood (Timonius sericeus (Desf) K. Schum), the bastard poon tree—kepuh (Sterculia foetida L), blackboard trees—pulai (Alstonia scholaris (L.) R.Br, Alstonia spectabilis R.Br), jackfruit trees (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lamk and Artocarpus integra Merr), and white-barked Acacia (Acacia leucophloea), which are found in the environments surrounding their settlements. Farmers also plant horticultural crops, such as pineapple (Ananas comosus Merr), soursop (Anona muricata), jackfruit trees (Artocarpus communis Forst, Artocarpus heterophyllus Lamk, Artocarpus integra Merr), achira (Canna edulis Ker), papaya (Carica papaya L.), pummelo (Citrus maxima (Burm) Merr), Taro—ubikeladi (Colocasia esculenta Schott), coconut (Cocos nucifera), asiatic yam (Dioscorea aculcata Linn and Dioscorea alata Linn), sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas Poir), mango (Mangifera indica), cassava (Manihot utilissima Pohl), banana (Musa parasidiaca Linn), avocado (Persea gratissima Gaertn), and turkey berry—terung pipit (Solanum torvum Swartz). Several NTFPs, such as betel nut palm—pinang (Areca cathecu), tamarind—asam (Tamarindus indica), and candle nut—kemiri (Aleurites moluccana) were developed around settlements, including plants that are useful for conservation, such as weeping fig—beringin (Ficus benyamina) and the blackboard tree (Alstonia scholaris), to increase the biodiversity, land conservation, and reforestation of areas around springs [86].

Based on the listed crops found in various places in Timor, most food crops were categorized as indigenous food crops cultivated for household consumption and income. The crops were planted simply following seasonality, and government intervention was very limited. Seed or planting materials were prepared by farmers themselves from the previous harvest season [87,88]. Most grains and seeds were stored in a traditional house called a Lopo, which is normally used for cooking. The smoke from firewood in the Lopo house protects the quality of seed materials, at least up to the next planting season [88,89,90].

5. Natural Vegetation Biodiversity in Relation to Livestock Farming

The diversity of vegetation not only in the farmland in Mamar—as previously mentioned, but also in the forest and grassland—supports integrated livestock farming in the region. Although livestock may consist of cattle, buffalos, horses, goats, sheep, pigs, and chicken, the most important practice in West Timorese is raising cattle. The general vegetation biodiversity—as well as crop and forest vegetation biodiversity—that supports the integration of livestock farming in West Timor includes the natural grassland ecosystem (consisting of native grasses and herbaceous legumes), native trees (consisting of legume and non-leguminous trees) in the savannah, Ladang (upland), or in the form of forests in Mamar. Native grass species in the native grasslands in this case include Heteropogon contortus, Ischaemum timorense, Sorghum timorense, Sorghum nitidum, Cenchrus polistachyon (syn.: Pennisetum polystachion), Rottboellia exaltata, and Bothriochloa pertusa. Cenchrus polystachion [98] and Rottboellia exaltata, especially, are annuals, which are usually cut and carried during the early wet season before they start to flower and are fed to cattle in the pen, playing an important role in fodder composition in West Timor for fattening cattle, though in many places these two annuals are considered weeds [99,100,101,102,103]. Other grasses are usually free grazed or fed to the animals by tethering them in communal native pastures. Several herbaceous legumes identified as important fodder components in native pastures included Aeschynomene americana, Alysicarpus vaginalis, Desmodium timorense (a broad leaf legume), Mucuna timorense (similar to M. pruriens, but it is more hairy and itchy), and Desmanthus virgatus. There are some naturalized species which were introduced into Indonesia a long time ago as cover crops in the estate crop plantations, including Macroptilium atropurpureum (Siratro), Centrosema molle (Syn.: Centrosema pubescens), and Calopogonium muconoides, which are found to grow naturally in native pastures, at road sides, in Ladangs, and at the edge of forests and bushes. Desmodium timorense (the broad leaf Desmodium in Timor) can be found sporadically in spots of native grasslands and are grazed by free-grazing animals (both goat and cattle); however, in the North Central Timor district, farmers cut and carry this as feed to fatten cattle [104,105].

The native legume trees found in West Timor include Acasia leucophloea and Acasia nilotica, which may be grazed by free-grazing cattle and goats when the plant sizes are within the reach of the animals, while the tall-growing plants may be climbed and cut down by the farmers to feed to the animals. The leaves of A. leucophloea contain a moderate–high protein content of 15–17% [106]; they are also an important source of dry season fodder and pasture trees in Pakistan, with 25% crude protein content in seeds [107], and of plant nectar for honey bees in Timor [9]. Some naturalized species that have been present for quite a long time include Glirisidia sepium, Sesbania grandiflora, and Leucaena leucocephala subsp. leucacephala (small common Leucaena) [98]. These small trees may be directly grazed by the animals or cut and carried as feed for animals in pens or at tethering places near to farmhouses. Both of the Acacias are commonly cut and carried during the long dry season on the island. The small type of Common Leucaena has been commonly used in the farming systems, especially in the Amarasi areas, in West Timor, as an effort to prevent Lantana camara infestation in the area, to improve the soil quality, and as a pioneer plant in the slash-and-burn method to shift cultivation. The plant is grown at a high density in a plot of land and will be cut down and burnt (slash-and-burn) in the land preparation season (before the wet season) before being planted with maize in the wet season. After this, the plant will be left to regrow and cover the land plot, and will be the same at the next land preparation stage, while during this time, the plant may be cut and carried as feed to fatten cattle near the farmhouses. Later, the introduction of the giant leucaena varieties (Leucaena leucocephala subsp. glabrata) in the 1970s, such as K8, K28, and K 500 (cv Cunningham), enriched the fodder sources of livestock farmers in West Timor, especially in the Amarasi area [98]. However, upon the attack of the psyllid insect (Heteropsylla cubana), a new variety (Leucaena leucocephala cv Tarramba) that was resistant to the insect was tested, promoted, and developed, especially for ruminant feeding [105,108].

Besides the tree legumes, there are some native trees of non-leguminous plant leaves that are important in providing highly nutritional fodder, especially during the mid to end of the dry season (August to November/December), for the livestock (cattle and goats), e.g., Macaranga tanarius (local name: Busi), Schleichera oleosa (local name: Kesambi), Ceiba petandra (lokal name: Kapok), and Ficus species (local name: Beringin). These trees are important during the dry season when grasses and herbaceous legumes are scarce. These non-leguminous trees, besides providing fodder during the dry season, and timber (or large to medium branches/trunks) obtained from logging the trees, as well as other trees such as Gum Trees (Eucalyptus species), would be important in building fences for food crop land plots during the planting season to prevent free-grazing animals from damaging the cultivated plants within the plot. Besides the mentioned feed obtained from native grasslands, food crop waste, and trees from forests and Ladangs, especially as a source of protein and fiber for ruminants, the Corypha gebanga (local name: Gewang) pith has been quite an important feed as a readily available carbohydrate (RAC) or energy source included in the local wisdom of West Timorese farmers for livestock farming. The pith of the C. gebanga can provide feed for cattle, goats, pigs, and chickens [109,110].

6. Local Wisdom on Soil Management

Prior to the arrival of the European ruler in Timor, the indigenous Timorese survived as hunters and gatherers on the less populated island and in the diverse environment [115,116]. Timorese people probably started farming in the 13th century [117], and incorporated some new food crops, which were later replaced by maize after contact with Indian and Chinese traders, and later with European traders [115,118,119]. In this section, a pearl of local wisdom refers to indigenous Timorese practices in upland farming that respect environmental and sustainability notions.

Most of the agricultural land on Timor Island is considered marginal or unfertile land/soil [118] compared to Indonesia’s western part. Coupled with low and erratic rainfall, farming, particularly food crop agriculture, encounters high risk and low productivity. Within this environment, Timorese farmers have developed farming strategies to maintain a level of food crop production for subsistence. Maintaining land productivity by local farmers is closely related to farm management, crop diversity, and crop residue management [120], while soil fertility is closely related to the length of the fallow period and succession vegetation [121].

There are three upland farming types on Timor Island [85]: (1) swidden agriculture (kebun/ladang), (2) local agroforestry (Mamar), and (3) house garden/farmyard (pekarangan/kintal). The first includes permanent plot cultivation (ladang permanent) and swidden plots or fallowed ladangs. The second refers to the dense mix of perennial crops and any other compatible plants in a relatively small parcel of land. It is considered the most stable, economic, and ecologically sound system. The last (house garden/farmyard) refers to the farmed land around or near farmers’ homes. These three types of farming reflect maximum use and compatible resources and minimize agriculture risk in marginal areas. Diversification is also a form of self-insurance [122,123,124], reducing vulnerability [125,126] and improving resilience [125,126,127].

There are five main indigenous ethnic groups settled in the western part of Timor Island, i.e., Meto, Tetun, Bunak, Kemak, and Marae [119]. The Meto ethnic group settled and dominated the western part of the island. Tetun mostly settled in the southern part of the Malaka District. Three other ethnicities settled in the Belu and Malaka districts. Although they share a common farming practice, these ethnic groups developed specific strategies to survive in their local environment.

Timorese farmers investigated suitable land for crops based on the vegetation and population density. They perceived that the denser the vegetation, the more fertile the soil. Upland farmers started land clearing for farming if they perceived that soil was productive enough to support agriculture for several years before it was fallowed to allow for natural revegetation. Besides vegetation, farmers also observed earthworm secretion as an indicator of the soil fertility.

An ancient food crop commodity in Timor was foxtail [117], followed by the introduction of a new food crop, Maize, which later became the main staple. The slash-and-burn system is a common practice in land preparation for a traditional system. There is almost no plowing—or, in other words, farmers practice minimum soil disturbance. Upland farming for food crops is conducted mainly on sloping land; therefore, minimum soil disturbance is considered to minimize soil erosion and promote the quick recovery of soil biology.

Traditional farming practices had little impact on the natural ecosystem of Timor Island, at least up to the beginning of the twentieth century. Farmers strictly controlled fire in swidden agriculture to avoid wildfire [5]. During land clearing, some vegetation remain uncut, primarily foraging three legumes. Leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala) trees are the most common and widely used for cattle feed and fertile soil recovery in swidden agriculture. This typical swidden cultivation is considered a productive system for at least forest–grassland succession and maintaining biodiversity [128].

To minimize the risk in food crop farming in Timor Island’s marginal areas, farmers practice a mixed-cropping pattern. To maintain or reduce soil fertility depletion, farmers have to combine different food crops that support one another or minimize competition in nutrient intake. Three main widely planted food crops are maize (Zea mays), pumpkin (Cucurbitaceae), and pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan). The composition of the three food crops depends on farmers’ preferences in considering land and climate prediction. These three food crops also reflect the main diet of the Timorese people.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14106023

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!