Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Gastroenterology & Hepatology

The Gram-negative bacterium Helicobacter pylori colonizes c.a. 50% of human stomachs worldwide and is the major risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma. Its high genetic variability makes it difficult to identify biomarkers of early stages of infection that can reliably predict its outcome.

- H. pylori

- biomarkers

- NGS

- WGS

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative spiral-shaped stomach bacterium first discovered by Marshall and Warren in 1984 [1]. H. pylori is a strict human pathogen that traces human migrations, present in 50% of human stomachs worldwide [2], being associated with gastritis, peptide ulcer, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma [3,4]. Interestingly, increased disease complications, such as gastric carcinogenesis, may be associated with H. pylori-induced epigenetic changes [5,6]. Accordingly, H. pylori has been classified as a class I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer since 1994 [7], being the strongest known risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma. Notably, H. pylori infection can also lead to extra gastric diseases [8,9]. In 2017, H. pylori was included in the World Health Organization priority pathogens list for research and development of new antibiotics for its persistent resistance to clarithromycin treatment [10]. H. pylori strains show very high genetic diversity [11], which is the result of unusually high mutation [12,13] and homologous recombination rates [14,15]. Due to these intrinsic characteristics and the complex interaction of many factors, such as the host genetic background and environmental factors, the identification of biomarkers of early stages of infection has been challenging over the years.

2. Technologies Used for H. pylori Marker Detection

To a greater extent than identifying biomarkers for antibiotic-resistance profiling and virulence potential evaluation of H. pylori strains, the choosing of working methods to access such information in each context is of major importance. Currently, the most common molecular approach involves PCR amplification of the region (or regions) of interest, followed by Sanger-sequencing and contrasting of the obtained sequence with the genome of a reference strain, such as H. pylori 26695, or sequence databases.

For antibiotic-resistance in specific, phenotypic evaluation procedures, such as the agar dilution method—the gold standard—and E-tests are still widely used [213], and are often the starting point for the identification of resistance-conferring mutations [168,176,187]. However, these methods, apart from being time-consuming, costly and technically demanding, are widely subjective and culture-dependent. Several genotypic molecular techniques have been described to overcome the limitations of phenotypic techniques [214]. Accordingly, some PCR-based methods for H. pylori biomarker detection have been developed [215,216,217,218]. Of note, in 2009, Cambau and colleagues developed a PCR-based DNA strip genotyping test allowing for simultaneous detection of H. pylori and mutations predictive of clarithromycin and levofloxacin resistance [219]. Despite some limitations [220], the GenoType® HelicoDR test is a simple and helpful test that produces better results when compared to histology- and culture-based methods [221].

With the advent of NGS technologies and the facilitated access to whole genome data, a novel perspective on H. pylori biomarkers and a range of new approaches to H. pylori study have been developed. A closer look at these new approaches is provided below.

3. New Approaches to H. pylori Biomarker Detection

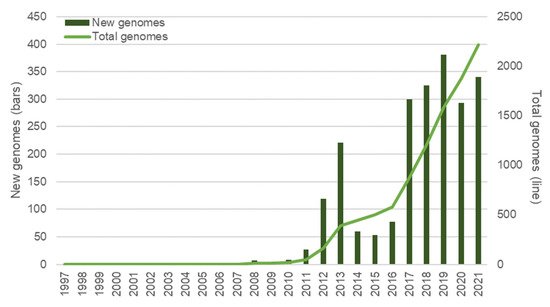

H. pylori was among the first bacterial species to have its genome fully sequenced [222] and was the first for which genomes of two independent isolates were sequenced and compared [223]. Twenty-five years later, the democratization of high throughput sequencing technologies that allow for the fast and massive acquisition of genomic data has cast a new light on the detection of H. pylori biomarkers related to both antibiotic resistance and virulence factors. As a result, the assessment of strain pathogenic capacity and the better choice of eradicating therapy is possible, saving precious time and resources in tackling this worldwide health problem (Figure 3). These new approaches enable several limitations of the previously referred to methods to be overcome and allow for a wider perspective on H. pylori biomarkers, pathogenicity and evolution. The importance and potential of whole genome data on bacterial pathogen evolution, virulence and pathogenicity has been acknowledged for over two decades [224] and we now have the technologies to get the best possible out of such data [225]. Presently (as of January 2022), a total of 2251 H. pylori genomes are recorded in the Pathosystem Resource Integration Center (PATRIC) database [226], reflecting the commitment of the scientific community to this technology (Figure 3). Curiously, the number of newly sequenced genomes diminished during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, with an apparent recovery in 2021 (Figure 3). The NGS systems mainly used for whole genome sequencing (WGS), as well as their advantages and disadvantages, have been reviewed elsewhere [227,228].

Figure 3. Overview of H. pylori genomes made available over time. Bars represent the new genomes released in each year; the total number of genomes available at each year is represented with a line. Data was retrieved from the PATRIC database [226] (last accessed in January 2022) and refer only to genomes submitted until the end of 2021; 34 genomes with no credible submission year were not taken into consideration for this graphic.

3.1. Sequencing Technologies

The most used sequence technology among studies assessing antibiotic resistance biomarkers or virulence factors was Illumina sequence-by-synthesis [26,71,144,229,230,231,232,233]. Interestingly, third-generation sequencing technologies, such as PacBio or Oxford Nanopore technologies, were used in either sole [170,234,235,236,237] or mixed approaches [238]. Different NGS approaches were also used, either for WGS [239,240,241,242], addressing, for instance, the correlation between genotypic markers and phenotype [243,244], or for amplicon sequencing, such as the cagPAI genes [245], or antibiotic-resistance biomarker genes [161]. In line with this, the accumulation of genomic data creates opportunities to reuse today’s data as new technologies, methods and perspectives arise.

Although most studies have extracted DNA for sequencing in a culture-dependent way, thus not overcoming this limitation, it is possible to obtain genomic data without culture [161]. Culture-independent whole-genome amplification, specifically targeting or not H. pylori sequences, was suggested to surpass the issue of the low amount of DNA retrieved from regular methods of acquisition [246]. Limiting the direct application of NGS technologies as an effective tool in combating H. pylori, some studies using whole genome data for the identification of virulence factors needed to use conventional PCR-based Sanger-sequencing to confirm the full sequence of genes [176,247,248,249,250]. As sequencing data increases in quality, confirmatory Sanger-sequencing is not also necessary and WGS data can be established as a culture-independent, objective, time- and cost-effective tool to obtain an integrated view of H. pylori genotypic characteristics and its pathogenic potential.

In recent years, American Molecular Laboratories (Vernon Hills, IL, USA) developed pyloriAR™/AmHPR®, an H. pylori antibiotic resistance NGS panel that targets the main genetic biomarkers associated with H. pylori antibiotic resistance [154,251], namely, the 23S rRNA gene (for clarithromycin), gyrA (fluoroquinolones), rdxA (metronidazole), pbp1 (amoxicillin), the 16S rRNA gene (tetracycline) and rpoB (rifabutin). To our knowledge, a similar approach focusing on virulence factor-biomarkers does not yet exist, but seems developable in the near future, potentially increasing the range of options regarding the application of NGS technologies in assessing the pathogenic capacity of H. pylori strains.

3.2. Virulence Potential Evaluation and Antibiotic-Resistance Profiling

Whole genome data provide the opportunity to evaluate the virulence potential of strains and to predict the resistance profile for several antibiotics from a single dataset, with no need for multiple cultures, PCR amplification or sequencing procedures. Regarding virulence factors, several studies have used whole genome data to establish an association between virulence factors and the pathogenic effect of strains, and to determine the pathogenic potential of H. pylori strains. The confirmation of virulence phenotype upon biomarker detection, however, is not simple due to the previously discussed complex relationship between virulence factors and phenotypic outcomes. Conversely, regarding antibiotic-resistance markers, several studies have addressed the coherence between genomic-based predictions of antibiotic resistance (with previously approached biomarkers) and the phenotypic evaluation of antibiotic resistance. Most studies found a very strong correlation between 23S rRNA markers for resistance and resistant phenotype [154,157,170], especially with the detection of the A2143G mutation [232], although not indisputably [160]. Regarding levofloxacin resistance, the literature reports a moderate to strong reliability for the detection of mutations on the gyrA gene [154,170,243]. Mutations on the pbp1 gene showed moderate to strong reliability for the prediction of amoxicillin resistance [154,155,160,252]. Less consistently, observations of metronidazole-resistance biomarkers have mostly been reported as fair predictors for metronidazole resistance [154,160,252], although some studies found only weak reliability for these observations [155,157,170]. Conversely, a good agreement between the truncated or mutated version of the rdxA gene and metronidazole-resistant phenotypes has been found [156]. A good correlation between the detection of 16S rRNA mutations and tetracycline resistance was also observed [160]. Furthermore, a close correlation between genotype data and phenotypic outcome has been observed [242]. Overall, existing studies suggest that genomic data can accurately predict antibiotic resistant phenotypes, especially for clarithromycin, levofloxacin and amoxicillin; however, it is necessary to highlight the importance of further research to uncover the complex phenotype-genotype correlation in H. pylori and to identify other antibiotic resistance mechanisms [242].

3.3. Current Tools as Possible Limiting Factors

When WGS data are obtained, efficient bioinformatics tools and representative databases are required to make the best use of such information in the characterization of antibiotic resistance. A wide set of sequencing-based tools for antimicrobial resistance detection and antimicrobial resistance reference databases have been reported and are available, as reviewed by Boolchandani and colleagues [253]. However, most of these tools are not particularly useful in the assessment of H. pylori resistance genotype, as resistance mechanisms in H. pylori are mainly based on point mutations, as previously noted, and these tools mainly focus on horizontally acquired genes [175]. Overcoming such limitations, the CRHP Finder webtool enables detection of most of the common mutations leading to clarithromycin resistance using H. pylori WGS data [254]. Additionally, the PointFinder tool recently integrated H. pylori information, allowing for the detection of point mutation-based resistance markers from WGS data [255]. Most studies, however, have compared the obtained sequences with the genome of the reference strains or susceptible strains, inferring sequence variations [161,167,176,240]. Regarding virulence factors, the ABRicate pipeline allows for the screening of genome contigs for virulence genes [26,238]. Since 2017, the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) has been expanded and currently contains reference sequences of H. pylori factors of virulence and antibiotic resistance conferring mutations, namely on the 16S and 23S rRNA genes [256]. Interestingly, as previously noted, the accumulation of genomic data is a huge advantage, not only regarding statistical power, but also regarding the potential to reuse present data with future tools that have not yet been developed.

3.4. New Applications: The Example of Methylome Analysis

As new methods and new tools are developed, the application range of NGS technologies becomes even wider and more interesting, allowing for different approaches and the recovery of different information. One of the most interesting and promising applications of NGS methods is the assessment of methylome data. The methylome is the set of methylation modifications and their location in a particular genome, and is dependent on restriction-modification systems [257]. H. pylori present a wide range of restriction-modification systems and is densely methylated across the genome with methylation patterns differing widely between strains [258,259]. Importantly, genome methylation status seems to impact gene expression, including virulence factors [257]. Consistently, specific genome methylation was shown to play an important role for colonization and pathogenesis of H. pylori [260]. Interestingly, the single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing developed by PacBio allows for the fast assessment of genome methylation status during sequencing-by-synthesis [228,257]. Complete methylome data and analysis were already reported for H. pylori strains [261,262]. The integrated analysis of methylome information, together with the previously discussed whole genome data, can thus be used to assess the pathogenic capacity of H. pylori strains. Again, with the natural development of new NGS technologies, new applications, such as methylome analysis, are anticipated, opening new perspectives for the integrated study of H. pylori genomic data.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom12050691

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!