2. Kazakhstan’s Environment and Hydrographic Network

The regime and flow of Kazakhstan’s rivers are governed by the Republic’s unique topography and climatic zoning, which ultimately determine the distribution of fish habitat. A vast nation covering 2.7 million km

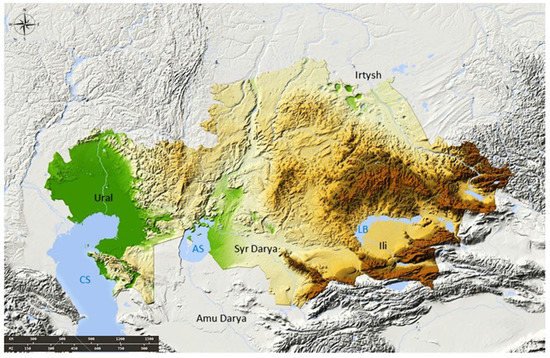

2 of the earth’s surface, Kazakhstan lies at the center of Eurasia (

Figure 1). Its climate is distinctly continental, with hot summers, cold winters, and large daily, seasonal, and annual fluctuations in air temperature [

24]. About 12% of the country is covered by piedmont areas and high mountains that receive the most precipitation and are located along the south and eastern borders [

25]. The remainder consists of low, arid drylands that are classified into five climatic zones from north to south: forest-steppe, steppe, dry steppe, semi-desert, and desert [

26]. Average annual precipitation declines from 270 mm in the steppe areas to just 120 mm in the desert zone.

Figure 1. Relief map of Kazakhstan. Higher elevations are shown in brown and lower elevations in green. The Ural, Irtysh, Ili, Syr Darya, and Amu Darya rivers are identified, as are three large lakes: the Caspian Sea (CS), Aral Sea (AS) in its mid-twentieth century form, and Lake Balkhash (LB). Credit: 123RF.com, accessed on 16 March 2022 and used with permission.

Most of Kazakhstan’s rivers originate in mountainous areas and are charged by seasonal snowmelt [

25,

27]. Spring floods are common, and drought periods routinely cause smaller streams to dry up as they flow across the arid lowlands [

28,

29]. The continental climate of Kazakhstan conditions sporadic drought in the summer and autumn [

27,

30], and this results in low water availability in some years and adequate or even excess water in others [

31,

32]. Although the Republic has more than 8000 rivers with lengths greater than 10 km, only 155 are more than 100 km in length and only seven flow for more than 1000 km. Just 53—less than 1% of the total—have an average annual water discharge of more than 5 m

3/s. The Republic’s rivers tend to be shallow, and although their total length is 10,500 km [

33], they form a very sparse network.

There are four significant rivers from the standpoint of capture fisheries: the Irtysh, Syr Darya, Ili, and Ural (

Figure 1) [

14]. About 180 reservoirs have been constructed, mainly for irrigation and hydroelectric energy, but some of them also provide important fish habitats. The largest, all of which have important fisheries value [

34], are the Bukhtarma and Shulba Reservoirs on the Irtysh River, Kapchagay Reservoir on the Ili River, and Shardara Reservoir on the Syr Darya River [

35]. The average annual water discharge rates of Kazakhstan’s four large rivers, all of which are transboundary, range from 350 m

3/s for the Ural to 800 m

3/s for the Irtysh. Although the rivers in Kazakhstan produce total water resources that average 100.5 km

3/year, almost half of this volume enters from neighboring countries that are increasingly diverting water for agriculture and industry [

35,

36].

Kazakhstan’s borders also enclose about 3000 lakes with surface areas greater than 1 km

2 and 22 with areas of more than 100 km

2; the total area covered by all lakes in Kazakhstan was nearly 2.9 million ha as of 1978 [

33]. Most are in the forest-steppe and steppe zones, but there are also lakes in the deserts of southern Kazakhstan. The total area of these waterbodies is about 45,000 km

2, two-thirds of which is of value for fisheries [

30]. Most of the lakes, including Lake Balkhash, the Republic’s largest water body, are nevertheless shallow, lack outlets, and because of the climate, subject to abrupt changes in water volumes and surface areas. Lake Balkhash, for example, has a current average depth of just 5.8 m. Fluctuations in inflows over the past few decades have caused its surface area to vary between 15,000 and 19,500 km

2 [

37]. This means that more than 4000 km

2 of the lake’s littoral waters, which are important sites for spawning and feeding fish, are subject to periodic desiccation [

38]. These unpredictable dynamics, which are not limited to Lake Balkhash, have potentially widespread detrimental impacts on the natural reproduction of fish stocks.

In addition to its inland lakes, Kazakhstan borders two large, shared bodies of saline water of longstanding importance for fisheries: the Caspian Sea and the Aral Sea [

13]. With a surface area of 378,000 km

2, the Caspian Sea is the world’s largest water body lacking an outlet to the ocean. The Volga and the Ural Rivers flow into the sea from the north and help maintain the degree of salinity at about one-third that of sea water, creating a unique environment for fish. Caspian sturgeon (

Acipenser spp.), which have been caught commercially since the seventeenth century [

39], are the source of the world’s most sought-after caviar and consequently of immense economic value [

40]. The Caspian Sea is subject to both anthropogenic threats due to pollution, especially from Azerbaijan [

41], and periodic natural fluctuations in its surface area [

42], which disrupt fish spawning in the shallow littoral zone along Kazakhstan’s extensive, 2300-km coastline.

The Aral Sea is much smaller than the Caspian Sea, and although historically valuable for fisheries, its importance never matched that of its larger sister [

13]. Fed by the Syr Darya and Amu Darya Rivers, the Aral Sea is well known as an object of human-caused environmental degradation due to ill-advised water withdrawals for irrigation [

43,

44]. It was reduced from a single waterbody with a surface area of 66,500 km

2 in the mid-twentieth century to a cluster of smaller waterbodies with a total surface area of just 10,000 km

2 as of 2017 [

45,

46]. Beginning in the early 1990s, the local community took steps to preserve one of these residual water bodies, Kazakhstan’s Small Aral Sea [

47]. In contrast to the other remaining areas, which appear destined for complete desiccation, its level and hydrological condition have now been stabilized [

45,

48], and thus from the perspective of Kazakhstan, the Aral Sea is now inland and not a shared resource. Commercially valuable fish have returned, as has a growing fisheries industry [

49,

50,

51].

3. The Soviet Fishing Sector and Its Implications for Kazakhstan

3.1. Early Development

It was not until the latter half of the nineteenth century that fishing became a significant activity in czarist Russia. Transportation systems were expanding, methods to preserve food were improving, and governance policies were being revised to meet the growing demand for fish products [

13]. In 1913, the eve of World War I and the 1917 revolution that would soon lead to the establishment of the Soviet Union, 83% of Russia’s fish capture was from inland waters, and three-quarters of this amount was from the Volga–Caspian basin [

52]. Domestic demand could nevertheless not be met, a situation that deteriorated during the war as resources were mobilized for fighting. The provisional government issued decrees during the winter of 1917–1918 to abolish private ownership of water resources; fisheries were nationalized, and numerous fishing firms were closed [

53].

Glavryba, the Directorate for Fish and the Fishing Industry in Russia, was established in October of 1918 and assigned comprehensive responsibilities for the administration, regulation, and production of fish. Five regional directorates termed

Oblastryba were also created and began to organize fishers into collectives [

53,

54,

55].

A surplus-appropriation system was imposed on the fishing sector during this period. Private fishers were declared to be state fishers, and all harvests were forcibly seized and transferred to the People’s Commissariat of Food, which took charge of distribution. The once-flourishing Volga–Caspian fisheries became a testing ground for the new political ideology, which funneled support to poorer, nonproductive peasants while denying it to the wealthier, most productive group of fishers [

56]. Lenin’s New Economic Policy of 1921 counteracted some of the damage caused by these stringent policies by restoring fishing firms, removing the state monopoly on fishing grounds, and allowing fishers to work privately and sell their own catches [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

The die for centralization had nevertheless been cast [

54]. Beginning with the first Five Year Plan for 1928–1932 and continuing until the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the Soviet fishing sector was issued production targets and provided with resources to achieve them. The Ministry of Fish Industry, which had existed in earlier forms until its establishment in 1939 and was reorganized several times thereafter [

58,

59], exerted vertical control over this process. The Ministry allocated production targets issued by the State Planning Committee of the Council of Ministers of the USSR (

Gosplan) to these units, one of which, the Caspian Sea Fisheries Directorate (

Kaspryba), reflected the importance attached to the Volga–Caspian basin.

The Ministry of Fishing Industry also controlled the entire supply chain, which grew to include a fleet of well-equipped fishing trawlers (some are especially designed for use on the Caspian Sea; see [

59]), a refrigerated transportation network, port infrastructure, and processing facilities that were assigned to the various

Oblastryba [

60,

61,

62]. A world-class research and fish conservation fleet was established, as were specialized research and educational institutions such as KaspNIRO, the Caspian Scientific Research Institute [

59], and the Kazakh Research Institute of Fisheries, which was created in 1959 under the auspices of the Kazakh Academy of Sciences. Moscow managed everything from the production of tin cans and fishing gear to quality control of fish products to the operation of supply and sales outlets [

13].

Glavrybvod, the Ministry’s Main Administration for the Preservation and Reproduction of Fish Stocks and the Regulation of Fisheries, had broad authority over Soviet fisheries, but it devolved responsibility for scientific and technical issues to subordinate regional agencies such as the Ministry of Fishing Industry of Kazakhstan and its predecessors, which also had jurisdiction over local fishing and fish processing associations [

13,

21,

59].

3.2. Characteristics of the Soviet Fisheries Sector

Commercial fishing in the Soviet Union was performed by either

solkhozy (state-owned enterprises) or

kolkhozy (cooperative enterprises). Fish harvested by

solkhozy were state property, but those caught by

kolkhozy belonged to the cooperative, which held all property communally and sold its fish to the government at a set price determined by the State Committee of the Council of Ministers.

Kolkhozy consequently achieved advantages of scale unobtainable by individual fishers [

13]. The All-Union Association of Fishery Kolkhozy and Cooperative Organizations was organized in 1931 to manage the affairs of

kolkhozy [

59], which by 1950 were responsible for more than 80% of catch from the Volga–Caspian basin [

52]. As many as 30

kolkhozy once operated on the Aral Sea [

63], and five were still in operation on Lake Balkhash when the Soviet Union disintegrated [

20].

Although more than one million people were eventually employed across the Soviet fisheries sector, investments were modest and recovery slow prior to World War II, which destroyed the Caspian fleet and processing facilities [

59]. The post-war Soviet Union again lacked sufficient agricultural resources to provide its population with animal protein, and so beginning with the 1946–1950 Five Year Plan, major investments were made to rebuild capacity in fisheries. Expenditures rose from 1.3 billion rubles between 1952 and 1958 to 1.7 billion rubles between 1966 and 1968, as

Gosplan increasingly turned its attention to the exploitation of lucrative ocean fishing grounds [

13,

64]. Beginning in 1965, the Ministry also introduced a bonus system of remuneration, which provided financial incentives to stimulate the production of fish products. Catches from inland waters remained essentially flat between 1930 and 1972, but those from ocean waters increased more than 14-fold during the same interval [

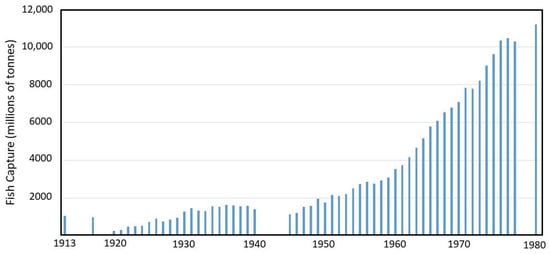

61]. Thus, although overall fisheries production increased rapidly (

Figure 2), exceeding 10 million tonnes for the first time in the mid-1970s, inland fisheries, including those in Kazakhstan [

65,

66], were losing their significance.

Figure 2. Commercial production of fish and other sea organisms in late czarist Russia (1913), immediately after the revolution (1917–1921), and in the Soviet Union (1922–1980). Data source: [

52].

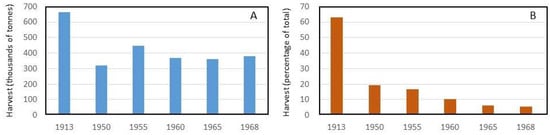

Fisheries in Kazakhstan achieved their greatest development during the Soviet era, but they also faced chronic challenges, none of which escaped the attention of Moscow. The once-dominant Volga–Caspian fisheries were reduced to insignificance by the 1960s (

Figure 3) and those on the Aral Sea ceased operation in the late 1970s [

67]. Dams were constructed to impound rivers and generate hydroelectric power, even though it was clear that their hydrological effects would damage fish habitats and interfere with fisheries [

68,

69,

70]. Pollution of waters used for fisheries was tolerated [

67,

71], and introduced species intended to bolster fisheries [

72,

73,

74] often disturbed fish populations without delivering the intended benefits [

33,

45,

72,

75]. Uncontrolled overfishing greatly exacerbated these problems [

76].

Figure 3. (

A) Commercial fish harvests from the Caspian Sea and (

B) fish harvests from the Caspian Sea as a percentage of the total Soviet production. Data sources: [

13,

52].

The Soviets undertook a number of steps to mitigate these challenges. Artificial reproduction was introduced to restore natural populations. This necessitated the construction of a network of fish hatcheries and breeding farms to produce immense numbers of juveniles to stock water bodies unable to maintain adequate fish populations under natural conditions [

33,

52,

77]. Reservoirs came to be viewed as assets for commercial fish production, and their numbers were increased [

64,

78]. High-value predatory fish species were also introduced into smaller lakes to eradicate low-value trash species [

11], and beginning in the 1930s, a substantial effort was also made to improve the food base for fish production by the introduction of invertebrates that could serve as prey [

33,

74,

79].

The first Soviet fish farms were established in the 1930s [

52,

59], and seven zones were defined, six in Kazakhstan [

80]. These facilities were assigned increasing priority, not just to propagate juveniles for release but also to elevate inland production of marketable fish. Raising fish in ponds was viewed as efficient use of land unsuitable for agriculture and a means to locate production near natural waterways (in the case of stocking) or population centers (in the case of marketable fish). Although fish production in ponds was plagued by inefficiency [

13] and the subject of constant complaints and recommendations for improvement [

52,

59,

64], stocking became an established practice. By 1968, 7.6 billion juveniles were being released annually into Soviet waterways [

13].

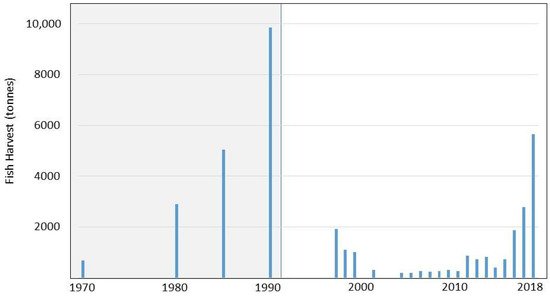

The yield of market fish from aquaculture increased dramatically in the mid-twentieth century, but it constituted a negligible 0.6% of total Soviet production [

13]. With the exception of the Volga–Caspian basin, where

kolkhozy emphasized the development of pond fisheries [

59], aquaculture was of little importance in Kazakhstan, where the first fish farm was established in 1937 [

11]. Production of marketable fish from ponds, which was just 692 tonnes in 1970, rose almost 15-fold over the following two decades (

Figure 4), but this constituted just 2.2% of the Soviet Union’s total aquaculture production [

11,

77].

Figure 4. Production of market fish from aquaculture in Kazakhstan. Harvests during the Soviet era are shaded. Data sources: [

11,

81].

Efforts to stabilize fish populations by protecting habitat and establishing fish farms, and stocking were augmented with policies to achieve what today would be called sustainable fisheries. Regulations were made more stringent, allowable catch sizes were reduced, and certain types of fishing gear were prohibited on some waterbodies [

11,

13,

52]. Outright bans were also put into effect, as in 1962 for sturgeon fishing in the Caspian Sea [

76]. These actions were only undertaken after extensive research and data analysis [

33,

64,

72].

3.3. Consumer Demand for Fish in the Soviet Union

Consumer demand played a major role in the development of the Soviet Union’s fisheries sector, and similar to other aspects of life in the USSR, Moscow sought to manage it (

Figure 5). Early preferences for fish were heavily influenced by products from the Caspian Sea, the major source of fish during the late czarist and early Soviet era [

59]. The Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR emphasized the nutritional aspects of fish consumption but paid little attention to cultural influences. The Commissar for External and Internal Trade designated Thursday as the All Soviet Fish Day of the Week in 1932 [

82,

83]. Canteens, cafeterias, and restaurants were obligated to serve fish on this day, and a cookbook soon appeared to, among other things, put more fish on the dinner table at home [

84]. New processing methods, strict attention to quality, and marketing through specialized shops were all deployed as tools to elevate consumption of the growing Soviet fish harvest [

13,

52,

59,

85]. As of the early 1970s, fully one-third of all animal protein consumed by Soviet citizens was supplied by fish [

60].

Targets to enhance fish consumption were also set by

Gosplan, which in 1976 announced the goal of increasing sales of fish by 25%. Even more ambitious targets were in place by the late 1970s, when efforts were underway to propel annual per capita consumption above the 18.2 kg per person then recommended by the USSR Academy of Sciences [

52]. Although average annual consumption rose from 6.7 kg in 1913 and 7 kg in 1950 to 16.8 kg in 1975 and 18.5 kg one year later, regional differences were pronounced. As of 1975, per capita annual fish consumption in Eurasia was estimated to be only about one-third that of the country as a whole [

86].