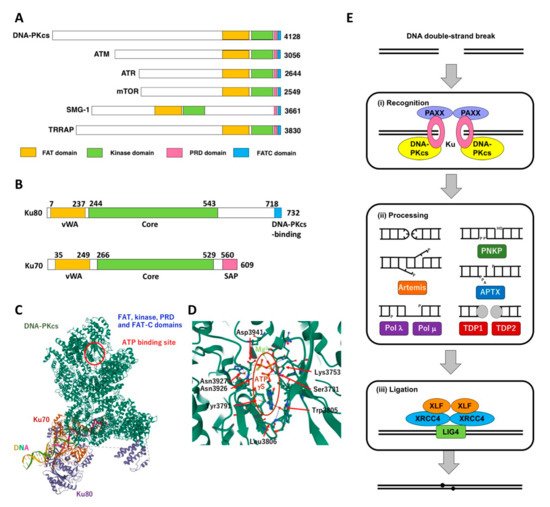

DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), which is composed of a DNA-PK catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) and Ku80-Ku70 heterodimer, acts as the molecular sensor for DSB and plays a pivotal role in DSB repair through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Cells deficient for DNA-PKcs show hypersensitivity to IR and several DNA-damaging agents. Cellular sensitivity to IR and DNA-damaging agents can be augmented by the inhibition of DNA-PK. A number of small molecules that inhibit DNA-PK have been developed.

- DNA double-strand break (DSB)

- non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)

- DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK)

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

1. DNA double-strand break repair

2. DNA-PK and Its Role NHEJ

|

Substrates |

Function |

Substrates |

Function |

|---|---|---|---|

|

[DNA Repair and Damage Signaling] |

[Transcription] |

||

|

(NHEJ) |

RNA polymerase II |

Transcription (general) |

|

|

DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) |

DNA-PK complex |

||

|

TATA box-binding protein (TBP) |

|||

|

Ku autoantigen 80kDa subunit (Ku80) |

p53 |

Transcription (specific) |

|

|

Specificity protein 1 (Sp1) |

|||

|

Ku autoantigen 70 kDa subunit (Ku70) |

c-Jun |

||

|

c-Fos |

|||

|

DNA ligase IV (LIG4) |

Ligation complex |

c-Myc |

|

|

X-ray repair cross-complementing group 4 (XRCC4) |

Octamer-binding factor 1 (Oct-1) |

||

|

XRCC4-like factor (XLF) |

Serum response factor (SRF) |

||

|

Artemis |

Nuclease |

[RNA metabolism] |

|

|

Polynucleotide kinase phosphatase (PNKP) |

Kinase, phosphatase |

Nuclear DNA helicase II (NDHII) |

Transcription and RNA processing |

|

Werner syndrome protein (WRN) |

Helicase, nuclease |

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNP-A1) |

RNA splicing |

|

(Other DNA repair and damage signaling pathways) |

|||

|

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) |

Protein kinase; HR and cell cycle checkpoint |

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U (hnRNP-U) |

|

|

Replication protein A 2 (RPA2) |

Single-stranded DNA binding; HR and DNA replication |

Fused in sarcoma (FUS) |

RNA binding |

|

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) |

Single-strand break repair |

[Signaling] |

|

|

Excision repair cross complementing 1 (ERCC1) |

Nuclease component; nucleotide excision repair |

Akt1 |

Protein kinase |

|

Akt2 |

Protein kinase |

||

|

[DNA replication] |

Sty1/Spc1-interacting protein 1 (Sin1) |

Protein kinase regulator |

|

|

DNA ligase I (LIG1) |

Ligation |

||

|

Minichromosome maintenance 3 (MCM3) |

Initiation of replication |

[Organelle, cytoskeleton] |

|

|

[Nucleosome and chromatin structure] |

Golgi phosphoprotein 3 (GOLPH3) |

Linking Golgi membrane to cytoskeleton |

|

|

Histone H2AX |

Core histone component; recruitment of DSB repair proteins |

Vimentin |

Intermediate filament |

|

Histone H1 |

Linker histone |

Tau |

Microtubule regulation |

|

High mobility group 1 (HMG1) |

Maintenance and regulation of chromatin structure |

[Protein maintenance] |

|

|

High mobility group 2 (HMG2) |

Heat shock protein 90 alpha (HSP90a) |

Protein chaperone |

|

|

C1D |

Valosin-containing protein (VCP) |

AAA+ ATPase |

|

|

Topoisomerase I |

Regulation of topological status of DNA |

[Metabolism] |

|

|

Topoisomerase II |

Fumarate hydratase (FH) |

Production of L-malate from fumarate; regulation of NHEJ |

|

|

Nuclear orphan receptor 4A2 (NR4A2) |

Chromatin regulation; regulation of NHEJ |

||

|

Pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG) |

Regulation of chromosome segregation |

||

References

- United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Report of the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation 2010 Fifty-seventh session, includes Scientific Report: summary of low-dose radiation effects on health.

- Zhao, B.; Rothenberg, E.; Ramsden, D.A.; Lieber, M.R. The molecular basis and disease relevance of non-homologous DNA end joining. Nat Rev Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 765–781.

- Yilmaz, D.; Furst, A.; Meaburn, K.; Lezaja, A.; Wen, Y.; Altmeyer, M.; Reina-San-Martin, B.; Soutoglou, E. Activation of homologous recombination in G1 preserves centromeric integrity. Nature 2021, 600, 748–753.

- Dvir, A.; Stein, L.Y.; Calore, B.L.; Dynan, W.S. Purification and characterization of a template-associated protein kinase that phosphorylates RNA polymerase II. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 10440–10447.

- Gottlieb, T.M.; Jackson, S.P. The DNA-dependent protein kinase: requirement for DNA ends and association with Ku antigen. Cell 1993, 72, 131–142.

- Hartley, K.; Gell, D.; Smith, C.; Zhang, H.; Divecha, N.; Connelly, M.; Admon, A.; Lees-Miller, S.; Anderson, C.; Jackson, S. DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit: a relative of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the ataxia telangiectasia gene product. Cell 1995, 82, 849–856.

- Savitsky, K.; Bar-Shira, A.; Gilad, S.; Rotman, G.; Ziv, Y.; Vanagaite, L.; Tagle, D.A.; Smith, S.; Uziel, T.; Sfez, S. et al. A single ataxia telangiectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3 kinase. Science 1995, 268, 1749–1753.

- Bentley, N.J.; Holtzman, D.A.; Flaggs, G.; Keegan, K.S.; DeMaggio, A.; Ford, J.C.; Hoekstra, M.; Carr, A.M. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad3 checkpoint gene. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 6641–6651.

- Cimprich, K.A.; Shin, T.B.; Keith, C.T.; Schleiber, S.L. cDNA cloning and gene mapping of a candidate human cell cycle checkpoint protein. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 2850–2855.

- Girard, P.M.; Riballo, E.; Begg, A.C.; Waugh, A.; Jeggo P.A. Nbs1 promotes ATM dependent phosphorylation events including those required for G1/S arrest. Oncogene 2002, 21, 4191-4199.

- Uziel, T.; Lerenthal, Y.; Moyal, L.; Andegeko, Y.; Mittelman, L.; Shiloh, Y. Requirement of the MRN complex for ATM activation by DNA damage. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 5612–5621.

- Zou, L.; Elledge, S.J. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003, 300, 1542–1548.

- Brown, E.J.; Albers, M.W.; Shin, T.B.; Ichikawa, K.; Keith, C.T.; Lane, W.S.; Schreiber, S.L. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature 1994, 369, 756–758.

- Sabatini, D.M.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Lui, M.; Tempst, P.; Snyder, S.H. RAFT1: A mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a Rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell 1994, 78, 35–43.

- Denning, G.; Jamieson, L.; Maquat, L.E.; Thompson, E.A.; Fields, A.P. Cloning of a novel phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinase: characterization of the human SMG-1 RNA surveillance protein. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 22709–22714.

- Yamashita, A.; Ohnishi, T.; Kashima, I.; Taya, Y.; Ohno, S. Human SMG-1, a novel phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related protein kinase, associates with components of the mRNA surveillance complex and is involved in the regulation of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 2215–2228.

- McMahon, S.B.; Van Buskirk, H.A.; Dugan, K.A.; Copeland, T.D.; Cole, M.D. The novel ATM-related protein TRRAP is an essential cofactor for the c-Myc and E2F oncoproteins. Cell 1998, 94, 363–374.

- Alemi, F.; Sadigh, A.R.; Malakoti, F.; Elhaei, Y.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Maleki, M.; Asemi, Z.; Yousefi, B.; Targhazeh, N.; Majidinia, M. Molecular mechanisms involved in DNA repair in human cancers: An overview of PI3k/Akt signaling and PIKKs crosstalk. Cell Phisiol. 2022, 237, 313–328.

- Huang, T.T.; Lampert, E.J.; Coots, C.; Lee, J.M. Targeting the PI3K pathway and DNA damage response as a therapeutic strategy in ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 86, 102021.

- Wanigasooriya, K.; Tyler, R.; Barros-Silva, J.D.; Sinha, Y.; Ismail, T.; Beggs, A.D. Radiosensitising Cancer Using Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase (PI3K), Protein Kinase B (AKT) or Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Inhibitors. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1278.

- Gewandter, J.S.; Bambara, R,A.; O’Reilly, M.A. The RNA surveillance protein SMG1 activates p53 in response to DNA double-strand breaks but not exogenously oxidized mRNA. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2561–2567.

- Gubanova, E.; Issaeva, N.; Gokturk, C.; Djureinovic, T.; Helleday, T. SMG-1 suppresses CDK2 and tumor growth by regulating both the p53 and Cdc25A signaling pathways. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 3770–3780.

- Zhang, C.; Mi, J.; Deng, Y.; Deng, Z.; Long, D.; Liu, Z. DNMT1 Enhances the Radiosensitivity of HPV-Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas via Downregulating SMG1. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 4201–4211.

- Long, D.; Xu, L.; Deng, Z.; Guo, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. HPV16 E6 enhances the radiosensitivity in HPV-positive human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by regulating the miR-27a-3p/SMG1 axis. Agent Cancer 2021, 16, 56.

- Chen, Y.H.; Wei, M.F.; Wang, C.W.; Lee, H.W.; Pan, S.L.; Gao, M.; Kuo, S.H.; Cheng, A.L.; Teng, C.M. Dual phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor is an effective radiosensitizer for colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 357, 582–590.

- del Peso, L.; González-García, M.; Page, C.; Herrera, R.; Nuñez, G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science1997, 278, 687–689.

- Datta, S.R.; Dudek, H.; Tao, X.; Masters, S.; Fu, H.; Gotoh, Y.; Greenberg, M.E. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell 1997, 91, 231–241.

- Zhou, B.P.; Liao, Y.; Xia, W.; Zou, Y.; Spohn, B.; Hung, M.C. HER-2/neu induces p53 ubiquitination via Akt-mediated MDM2 phosphorylation. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 973–982.

- Oeck, S.; Al-Refae, K.; Riffkin, H.; Wiel, G.; Handrick, R.; Klein, D.; Iliakis, G.; Jendrossek, V. Activating Akt1 mutations alter DNA double strand break repair and radiosensitivity. Rep. 2017, 7, 42700.

- Mueck, K.; Rebholz, S.; Harati, M.D.; Rodemann, H.P.; Toulany, M. Akt1 Stimulates Homologous Recombination Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks in a Rad51-Dependent Manner. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2473.

- Bozulic, L.; Surucu, B.; Hynx, D.; Hemmings, B.A. PKBalpha/Akt1 acts downstream of DNA-PK in the DNA double-strand break response and promotes survival. Cell 2008, 30, 203–213.

- Liu, L.; Dai, X.; Yin, S.; Liu, P.; Hill, E.G.; Wei, W.; Gan, W. DNA-PK promotes activation of the survival kinase AKT in response to DNA damage through an mTORC2-ECT2 pathway. Signal 2022, 15, eabh2290.

- Yaneva, M.; Wen, J.; Ayala, A.; Cook, R. cDNA-derived amino acid sequence of the 86-kDa subunit of the Ku antigen. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 13407–13411.

- Reeves, W.H.; Sthoeger, Z.M. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding the p70 (Ku) lupus autoantigen. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 5047–5052.

- Mimori, T.; Hardin, J.A. Mechanism of interaction between Ku protein and DNA. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 10375–10379.

- Falck, J.; Coates, J.; Jackson, S.P. Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage. Nature 2005, 434, 605–611.

- Walker, J.R.; Corpina, R.A.; Goldberg, J. Structure of the Ku heterodimer bound to DNA and its implication for double-strand break repair. Nature 2001, 412, 607–614.

- Chen X, Xu X, Chen Y, Cheung JC, Wang H, Jiang J, de Val N, Fox T, Gellert M, Yang W. Structure of an activated DNA-PK and its implications for NHEJ. Cell 2021, 81, 801–810.

- Liang, S.; Thomas, S.E.; Chaplin, A.K.; Hardwick, S.W.; Chirgadze, D.Y.; Blundell, T.L. Structural insights into inhibitor regulation of the DNA repair protein DNA-PKcs. Nature 2022, 601, 643–648.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Asa A.D.D.C..; Modak, C.; Shimada M. DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit: the sensor for DNA double-strand breaks structurally and functionally related to Ataxia telangiectasia mutated. Genes 2021, 12, 1143.

- Taccioli, G.E.; Gottlieb, T.M.; Blunt, T.; Priestley, A.; Demengeot, J.; Mizuta, R.; Lehmann, A.R.; Alt, F.W.; Jackson, S.P.; Jeggo, P.A. Ku80: product of the XRCC5 gene and its role in DNA repair and V(D)J recombination. Science 1994, 265, 1442–1445.

- Smider, V.; Rathmell, W.K.; Lieber, M.R.; Chu, G. Restoration of X-ray resistance and V(D)J recombination in mutant cells by Ku cDNA. Science 1994, 266, 288–291.

- Blunt, T.; Finnie, N.J.; Taccioli, G.E.; Smith, G.C.; Demengeot, J.; Gottlieb, T.M.; Mizuta, R.; Varghese, A.J.; Alt, F.W.; Jeggo, P.A. Defective DNA-dependent protein kinase activity is linked to V(D)J recombination and DNA repair defects associated with the murine scid mutation. Cell 1995, 80, 813–823.

- Kirchgessner, C.U.; Patil, C.K.; Evans, J.W.; Cuomo, C.A.; Fried, L.M.; Carter, T.; Oettinger, M.A.; Brown, J.M. DNA-dependent kinase (p350) as a candidate gene for the murine SCID defect. Science 1995, 267, 1178–1183.

- Peterson, S.R.; Kurimasa, A.; Oshimura, M.; Dynan, W.S.; Bradbury, E.M.; Chen, D.J. Loss of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase in DNA double-strand-break-repair mutant mammalian cells. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 3171–3174.

- Ochi, T.; Blackford, A.N.; Coates, J.; Jhujh, S.; Mehmood, S.; Tamura, N.; Travers, J.; Wu, Q.; Draviam, V.M.; Robinson, C.V.; et al. DNA repair. PAXX, a paralog of XRCC4 and XLF, interacts with Ku to promote DNA double-strand break repair. Science 2015, 347, 185–188.

- Xing, M.; Yang, M.; Huo, W.; Feng, F.; Wei, L.; Jiang, W.; Ning, S.; Yan, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; et al. Interactome analysis identifies a new paralogue of XRCC4 in non-homologous end joining DNA repair pathway. Commun. 2015, 6, 6233.

- Craxton, A.; Somers, J.; Munnur, D.; Jukes-Jones, R.; Cain, K.; Malewicz, M. XLS (c9orf142) is a new component of mammalian DNA double-stranded break repair. Cell Death Diff. 2015, 22, 890–897.

- Moshous, D.; Callebaut, I.; de Chasseval, R.; Corneo, B.; Cavazzana-Calvo, M.; Le Deist, F.; Tezcan, I.; Sanal, O.; Bertrand Y.; Philippe, N.; et al. Artemis, a novel DNA double-strand break repair/V(D)J recombination protein, is mutated in human severe combined immune deficiency. Cell 2001, 105, 177–186.

- Ma, Y.; Pannicke, U.; Schwarz, K.; Lieber, M.R. Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell 2002, 108, 781–794.

- Li, Z.; Otevrel, T.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, H.; Seed, B.; Stamato, T.; Taccioli, G.E.; Alt, F.W. The XRCC4 gene encodes a novel protein involved in DNA double-strand break repair and V(D)J recombination. Cell 1995, 83, 1079–1089.

- Critchlow, S.; Bowater, R.; Jackson, S. Mammalian DNA double-strand break repair protein XRCC4 interacts with DNA ligase IV. Biol. 1997, 7, 588–598.

- Grawunder, U.; Wilm, M.; Wu, X.; Kulesza, P.; Wilson, T.; Mann, M.; Michael, R.; Leiber. Activity of DNA ligase IV stimulated by complex formation with XRCC4 protein in mammalian cells. Nature 1997, 388, 492–495.

- Buck, D.; Malivert, L.; de Chasseval, R.; Barraud, A.; Fondanèche, M.C.; Sanal, O.; Plebani, A.; Stéphan, J.L.; Hufnagel, M.; le Deist, F. et al. Cernunnos.; a novel nonhomologous end-joining factor.; is mutated in human immunodeficiency with microcephaly. Cell 2006, 124, 287–299.

- Ahnesorg, P.; Smith, P.; Jackson, S.P. XLF interacts with the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Cell 2006, 124, 301–313.

- Hammel, M.; Yu, Y.; Fang, S.; Lees-Miller, S.P.; Tainer, J.A. XLF regulates filament architecture of the XRCC4·ligase IV complex. Structure 2010, 18, 1431–1442.

- Kienker, L.J.; Shin, E.K.; Meek, K. Both V(D)J recombination and radioresistance require DNA-PK kinase activity, though minimal levels suffice for V(D)J recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 2752–2761.

- Kurimasa, A.; Kumano, S.; Boubnov, N.; Story, M.; Tung, C.; Peterson, S.; Chen, D.J. Requirement for the kinase activity of human DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit in DNA strand break rejoining. Cell Biol. 1999, 19, 3877–3884.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Sharma, M.K. DNA-dependent protein kinase in DNA damage response: Three decades and beyond. Radiat. Cancer Res. 2020, 11, 123–134.

- Sehnal D, Bittrich S, Deshpande M, Svobodová R, Berka K, Bazgier V, Velankar S, Burley SK, Koča J, Rose AS. Mol* Viewer: modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 431–437.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23084264