Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation comprises the region of the electromagnetic spectrum (EM) between visible light and X-rays (100–400 nm). It was discovered in 1801 by Johann Wilhelm Ritter, who observed that radiation outside the violet end of the visible solar spectrum could decompose silver chloride. Seven decades later, it was discovered that UV light could prevent microbial growth.

- UV

- UVB

- UVC

- UV illumination

- photochemical treatments

1. Introduction

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation comprises the region of the electromagnetic spectrum (EM) between visible light and X-rays (100–400 nm) [1]. It was discovered in 1801 by Johann Wilhelm Ritter, who observed that radiation outside the violet end of the visible solar spectrum could decompose silver chloride [2]. Seven decades later, it was discovered that UV light could prevent microbial growth [3].

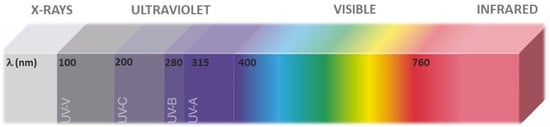

The UV region is frequently divided into three sub-regions, UVA (315–400 nm), UVB (280–315 nm), and UVC (100—280 nm) (Figure 1), which are used for CIE and ISO standards [4]. Further sub categorization has been performed by some authors to discriminate within the UVC region vacuum UV (100 and 200 nm) with stronger ionizing power, but less penetration [5,6,7]. Based on the known mechanisms of plant photoreception, the UVA region has been split into short-UVA (315–350 nm) and long-UVA (350–400) [8].

Figure 1. Subregions of the UV spectrum relevant for technological applications and plant photoreception.

2. UV Radiation Sources

Commercially available UV sources include mercury lamps (low- and medium-pressure), pulsed light (PL), and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [9]. Although the market has become highly dynamic with the improvement of LEDs, it is still dominated by mercury lamps. These sources are based on the excitation of gas discharges and feature several pitfalls, including a relatively high voltage requirement to operate and a substantial amount of heat released [10]. However, one advantage is that, especially with medium-pressure Hg lamps, high output powers can be achieved.

Xenon inert-gas lamps were introduced during the late 1970s in Japan, leading to the development of sterilizing technology, called PureBright® [11]. PL treatments consist in the exposure of fresh produce to polychromatic light (200–1100 nm), including ultraviolet (180–400 nm), visible (400–700 nm), and near-infrared (700–1100 nm) wavelengths, in the form of intense, but short, pulses (1 μs–0.1 s) [12,13].

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are based on the junction of two-terminal semiconductors (p-n junction) converting electricity into radiation. Depending on the materials out of which the semiconductors are made, the LEDs emit at different wavelengths [14]. The first LEDs, in the early 1960s, emitted infrared (IR) light. Over the years, it became possible to develop LEDs of shorter wavelengths. UV LEDs have several advantages relative to mercury lamps, including their lack of requirement for warming time, their lack of mercury, their compactness, their robustness (with UV LEDs, no protection against glass breakage is necessary, and mobile use is possible), and their large wavelength diversity (210 nm to 360 nm by varying the aluminum content in the AlGaN quantum wells) [10]. In addition, they have lower electromagnetic interference, are easily adaptable for fast modulation in terms of radiation intensity and pulse duration, present narrow-band emission without spurious peaks, and require low maintenance [15]. Two important advantages of LEDs are their long lifespan (expected lifetimes of many 10,000 s of h) and low heat emission [16]. The Achilles heel of UV LEDs is their relatively low quantum efficiency [17]. However, in recent years, by reducing dislocations and defects and improving semiconductor doping and light extraction, their quantum efficiency has been increased [18].

3. Uses in the Food Industry

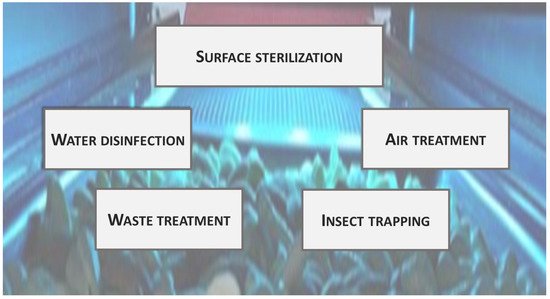

UV technology has been applied in the food industry for many different purposes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. UV radiation applications in the food industry.

Surface sterilization: One of the most common uses of germicide UVC lamps is as environmental sterilizers in foodstuffs filling equipment, conveyor belts, containers, and working surfaces [19,20]. Sterilizing UV lamps are frequently used for aseptic packing, a technology that is expected to continue growing in the coming years [21,22].

Fluid disinfection: UV radiation in the C zone has been used for water disinfection since 1909. It has been also applied for juice pasteurization [23]. UVC does not generate undesirable by-products, but on the other hand, it does not provide residual disinfection capacity [24]. It has been applied to reduce chlorine use.

Air treatment: Air disinfection can be achieved through different strategies, ranging from irradiating just the air in the upper region to treating all air, either when the room is empty or during circulation through air-conditioning systems [25]. The fact that UVC relatively low radiation doses (0.1–0.3 kJ m−2 for 2 log cycle reductions) can inactivate human SARS-coronaviruses has increased the recent interest in using UV radiation for air treatment [26,27,28].

Waste treatment: Another application of UV radiation has been the elimination of undesirable volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in industrial exhausts [29,30]. This has been achieved through advanced oxidation processes combining UV radiation with photocatalysts, such as TiO2 [9,31]. This strategy generates highly oxidative environments, which facilitates the degradation of unwanted molecules [32].

Insect trapping: For a long time, it has been known that UV radiation can attract insects; thus, it is used for trapping purposes [33]. The most common insect light traps use “black-light” fluorescent tubes emitting ultraviolet (UVA) as an insect attractant in both pre and postharvest [34]. Furthermore, insects may be trapped in glued materials or killed in electrically charged grids [35].

4. Uses in Fruits and Vegetables Postharvest

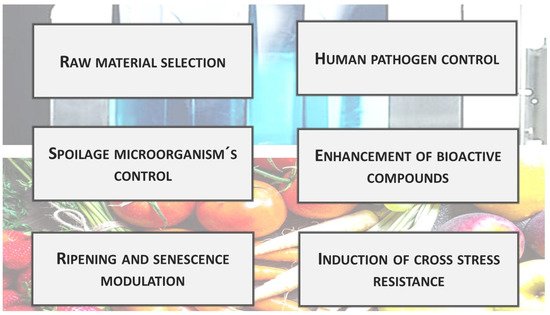

UV technology may be of interest for the postharvest treatment of fruits and vegetables for many different purposes [36,37] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Main uses of postharvest UV treatments for direct application in fruit and vegetables.

Raw material selection: The presence of skin defects or wounding is a main factor affecting consumer acceptability and purchase decisions. Consequently, one of the most intensive activities of packinghouses is to separate fruit with these defects. Normally, this is performed through visual inspection or machine optical sorting when the fruit is illuminated under proper white light [38]. In citrus, the use of UV lamps during initial classification has may facilitate the identification of physical damages. UVA “black light” illuminates fruit, showing that small peel cracks fluoresce intensely, allowing segregation at early classification steps [39]. The conveyor belts transporting the fruit cross these rooms, where the operators must wear protective glasses and gloves.

Control of spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms: Relying on UVC germicide properties, a large body of research evaluated this technology in fruits and vegetables to control surface microorganisms [40]. Microbial death induced by UVC has been attributed to DNA mutations, including the formation of cyclobutyl-type dimers (pyrimidine dimers) and pyrimidine adducts [41,42]. Furthermore, the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by UV radiation can oxidize membrane lipids and inhibit critical cellular enzymes [43]. Most enzymes that contain aromatic amino acids are likely to be sensitive to UV radiation to some extent due to their absorption in this region. Due to its higher energy, UVC is the most effective at killing microorganisms [44]. UV radiation is lethal to bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and fungi [45]. Successive studies showed that UV radiation is more efficient for inactivating Gram-negative than Gram-positive bacteria. This effect has been associated with the difference in the cell wall peptidoglycan structure, which can affect radiation penetration [46]. Furthermore, eukaryotic organisms are normally more resistant to UV than bacteria due to their higher cell size, complexity, and genetic redundancy [47]. The relatively high yeast resistance to UV radiation has also been associated with lower DNA pyrimidine content relative to bacteria, which may increase the likelihood of photons being absorbed by other compounds [48].

Several works have studied the impact of postharvest pre-storage single exposure on most common postharvest fungal pathogens, including Rhizopus, Penicillum digitatum, P. expansum and Penicillum italicum, Monilinia sp., Botrytis cinerea, Colletrichcum sp. and Fusarium sp. among others [49,50], with positive effects with regards to reducing disease incidence and severity. Direct germicide action compromising microbial viability has been frequently reported [51], but less severe effects, such as the reduced germination speed of viable conidia, have also been observed [52]. With regards to human pathogens, the direct UV irradiation of fresh produce reduced the viability of E. coli, Salmonella, and Listeria [53,54,55,56,57]. These studies have so far mostly been conducted on a laboratory or, in the best scenario, pilot scale. A review of the available research suggests that their widespread commercial use requires some important aspects to be solved, especially with regards to the adaptability of this treatment to continuous processing lines (where the treatment duration may require minutes at low irradiances), safety procedures for workers and even radiation exposure, while avoiding mechanical damage, especially to fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, the fact that wet cleaning methods have long been applied to fresh produce could limit the fast adoption of a different technology.

The mechanisms through which UV prevents deterioration exceed radiation germicide properties and involve host-induced physiological responses [58,59,60]. They include the inhibition of ripening-related genes [61] and the induction of enzymes and compounds, improving tolerance to opportunistic pathogens or other environmental effectors causing oxidative damage. An array of defensive responses has been observed in UV-stressed tissues. It includes the activation of glucanases and chitinases thought to be involved in the degradation of microbial cell walls, the induction of genes related to phenolic compound biosynthesis or oxidation, such as phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), polyphenol oxidases (PPOs), and peroxidases (PODs) [62,63]. Another frequent change reported is the upregulation of gene coding for antioxidative enzymes, such as superoxide dismutases (SODs), ascorbate peroxidases (APXs), and catalases (CATs) [64]. More recently, Rabelo et al. [65] proposed that the UV response is mediated by the generation of oxidative stress as the primary signaling molecule generated through the partial ionization of water and an increase in mitochondrial activity. With regards to the induction of compounds that could contribute to increasing host tolerance to pathogen attack, there have been several reports on metabolites with direct antimicrobial activity (i.e., hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, 6-methoxymellein, scoparone, scopoletin, rishitin), or reinforcing structural barriers [49,66]. Phenolic compounds showing in many cases antimicrobial and antioxidant properties have been the most frequently identified family of induced antimicrobial compounds.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/foods11050653

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!

Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia