1. Group I mGluRs in Parkinson’s Disease

1.1. Alterations in Basic Signalling

Group I mGluRs have distinct roles and functions in the brain, which have not been well characterised, specifically in disease pathology such as PD. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of a chronic PD rat striatum showed transiently increased expression of mGluR1, but not mGluR5, which dramatically decreased with disease progression

[1]. In addition, dynamic changes in mGluR1 during disease progression correlate with striatal dopamine transporter downregulation, indicating a correlation with a pathological decrease in general motor activity. Evidence suggests that mGluR5-mediated neurotransmission increases PD and leads to levodopa (L-DOPA)-induced dyskinesia (LID); LID could result from aberrant dopamine-related neural plasticity at glutamate corticostriatal synapses in stratum

[2].

The binding potential of the mGluR5 receptor has been seen decreasing in the bilateral caudate-putamen (CP), ipsilateral motor cortex, and somatosensory cortex, eventually in both PD and LID pathology. However, 6-OHDA-induced PD rats did not show any significant alteration in mGluR5 binding potential in those regions upon L-DOPA treatment

[3]. L-DOPA treatment substantially increased mGluR5 uptake at the contralateral motor cortex and somatosensory cortex and has been found positively related with abnormal involuntary movement. However, acute regulation of mGluR5 in the cortical astrocytes causes oscillatory Ca

2+ and synaptic release of neurotransmitters. Certain changes in Ca

2+ signalling might bring about interaction between mGluR5 and NMDA receptors; it has been evident in rat hippocampus that mGluR5 enhanced phosphorylation of NR2B

[4]. This evidence suggests that negative allosteric modulation of mGluR5 or any of group I mGluR may provide symptomatic alleviation in Parkinson’s disease via reducing overstimulation of basal ganglia nuclei.

1.2. Interaction with α-Synuclein

Aggregation of oligomeric αS species, synaptic dysfunction, and subsequent neuronal cell death are the key pathophysiological feature of synucleinopathy, including PD, which is known, but the precise molecular mechanism or the nature of toxicity during aggregation is unclear. Recent PD-related ones concentrate on extracellular soluble αS oligomers because of their critical role in PD pathogenesis and progression. It is now supposed that αS is released and propagates between neurons in a prion-like fashion

[5], so different αS species (monomers, multimers, oligomers, and fibrils) obtain access to the extracellular space, and their postsynaptic action impairs neuronal communication and plasticity. Inconsistent with this hypothesis, a recent one showed that PrP

C plays the role of cell surface binding associate for β-sheet-rich protein aggregates

[6][7][8], precisely soluble oligomeric αS via NMDAR activation, evoked by mGluR5

[5]. Oligomeric species of αS interact with PrP

C via mGluR5, activate Src tyrosine kinase family (SFK) kinase and NMDAR2B, and causes synaptic dysfunction

[5]. Thus, blockade of mGluR5-mediated NMDAR phosphorylation could rescue them from synucleinopathies by harmonising synaptic and cognitive functions.

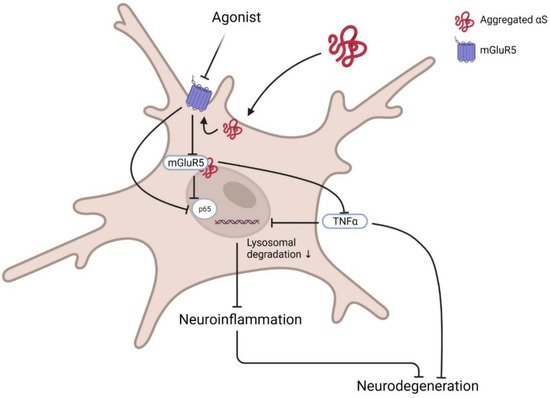

Contrarily, selective modulation of mGluR5 degradation and its intracellular signalling showed protection against αS neurotoxicity in microglia. mGluR5, but not mGluR3, selectively binds to αS at the N-terminal region. This interaction promotes lysosomal degradation of mGluR5 and abrogates neuroinflammation mediated by αS. Treatment with mGluR5 agonist CHPG, not antagonist MTEP, rescued them from αS-induced microglial activation and cytokine release by reducing nuclear factor κB (p65) and TNF-α activation

[6][9] (

Figure 1). Although it is still to be assured that activation or deactivation of mGluR5 in specific brain cells or regions could protect neuronal cytotoxicity, it is confirmed that the mGluR5-αS complex has a crucial role in PD pathology, and dissociation of this complex could modify pathogenicity.

Figure 1. Basic pathway of mGluR5 agonist in PD. Post activation of microglia by the presence of αS at the membrane inactivates membrane receptor mGluR5 and its downstream G-protein. Sequentially activated transcription factors NFκB p65 and TNFα enhance inflammatory cytokine release and induce neurodegeneration. Agonists such as CPHG could ameliorate this pathway by increasing mGluR5 expression via reducing lysosomal degradation, further downregulating related inflammatory signalling activation and subsequent inhibition of microglia-mediated inflammation to prevent neurotoxicity. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 31 March 2022).

1.3. Modulation of Apoptotic Signalling

The signal transduction of group I mGluRs has a diverse role in neurogenesis, neural progenitor cell proliferation, differentiation, and protection. Contrarily, both genetic and pharmacological blocking of group I mGluRs negatively affects cortical, hippocampal and striatal progenitor cell growth and survival

[10]. mGluR5 activation also promoted cerebellar granule cell survival

[11] and increased release of soluble β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) derivatives from the cortex and hippocampus that protects from neurotoxicity in AD

[12].

Although mGluR5 activation has been important for neuronal survival and proliferation, overactivation of glutamatergic transmission promotes dopaminergic neuronal loss. Thus, selective modulation of this excitatory neurotransmitter has been proposed as a promising target in PD. As mGluR5 is widely distributed throughout the basal ganglia, selective antagonism of this receptor by MPEP/MTEP or negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) has been shown to promote neuroprotection in PD

[13]. Selective modulation of group I mGluRs was found to inhibit toxicant or environmental stress-induced dopaminergic neuronal loss via modulating PI3K and JNK phosphorylation

[14]. Specific modulation of mGluR5 via cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance-regulator-associated ligand (CAL) could prevent rotenone-induced neuronal apoptosis in PD via AKT and ERK1/2 phosphorylation

[13]. These were suggested that selective modulation, but not blockade, of group I mGluRs could protect from apoptotic cell death in PD. Accordingly, it was confirmed that mGluR5 knockout was shown to inhibit oxygen–glucose deprivation-induced astrocytic deaths but did not protect from necrotic cell death

[15]. In response to oxygen–glucose deprivation, mGluR5 stimulates Gαq/11 and activates downstream PLC, which interacts with IP3. This interaction results in an increased level of intracellular Ca

2+ release and cell death. To protect from mGluR5-mediated apoptotic cell death, the blockade of mGluR5 by selective antagonist MPEP/MTEP showed sufficient protection against apoptotic cell death of cortical astrocytes

[14]. Up-regulation of mGluR5 selectively regulates apoptosis via PLC and increasing intracellular Ca

2+. Additionally, targeting mGluR5 activation and mGluR5–Homer interaction could counteract this scenario by modulating intracellular Ca

2+ release and astrocytic apoptosis.

Primarily, inhibition of caspase activation prevents cellular apoptosis; however, recently it has been seen that inhibition of caspase-dependent apoptosis shifts the programmed cell death pathway towards necrosis

[16]. Necrosis is an unregulated form of cell death characterised by cell swelling and disruption

[17]. However, the regulated version of necrosis is necroptosis, regulated by a specific stimulus such as RIP1 kinase or MLKL. Although the relation of metabotropic glutamate receptor activation or inhibition and necrosis has not been established yet, activation of mGluR groups II/III showed neuroprotection via inhibition of necroptosis

[18]. Both orthostatic agonist and PAM of mGluR II/III modulated caspase-3 activation reduced necrotic nuclei and up-regulated pro-survival ERK1/2 phosphorylation MPP+-treated differentiated SH-SY5Y dopaminergic cells of a PD model. Inhibiting group I and stimulation of group II/III could be beneficial for motor symptom improvement in PD and reduced dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra

[19][20]. Thus, it is speculated that group I mGluR plays some role in necroptosis, which has not been evaluated yet.

2. Neuroimaging of Group I mGluRs for Diagnosis and Therapeutic Development

The progression of PD significantly fluctuates glutamate receptors expression. Thus, a specific group I mGluR tracer could image the stage-to-stage progression of PD, which could help with therapeutics development. For example, longitudinal positron emission tomography (PET) imaging using [11C]ITDM (N-[4-[6-(isopropylamino) pyrimidin-4-yl]-1,3-thiazol-2-yl]-N-methyl-4-[11C]methylbenzamide) and (E)-[11C]ABP688 [3-(6-methylpyridin-2-ylethynyl)-cyclohex-2-enone-(E)-0-[11C] methyloxime] ligands for mGluR1 and mGluR5, respectively, showed dramatic changes in striatal non-displaceable binding potential (BPND) values of both receptors with PD progression

[1]. Analysing striatal BPND values for both receptors revealed that mGluR1, not mGluR5, increases temporarily at the early onset of PD symptoms and declines with the pathological progression of the disease. Furthermore, this decrease of striatal mGluR1 is associated with impaired general motor activities. However, another one

[21] used both DAT imaging agent [11C]PE2i and mGluR5 antagonist [18F]FPEB. They reported that DAT tracers are better-diagnosing tools for PD, while together with mGluR5 tracers, regional neurotransmitter abnormality could be explained, while probing with radioligands such as [11C]ABP688 or [18F]FPEB could measure availability and interaction with mGluR5

[22]. Although these showed the potential application of glutamatergic tracers in PD diagnosis, measuring true biological differences using them is yet a concern. For example, [18F]FPEB showed dilute dorsal striatum of mGluR5 but concentrated in the ventral striatum in reality, which is vice-versa. It warrants further exploration of mGluR5 tracers to convert them into potential biomarkers.

Neuroimaging could identify specific preferential binding sites that could reveal a new pharmacological target. Autoradiography using radioligand [3H]AZD9272 revealed fenobam, selective mGluR5 antagonist, ventral striato–pallido–thalamic circuit binding potential

[23]. Like AZD9272, fenobam also showed psychosis-like phenomena during clinical trials

[18], associated with both compounds binding to different brain regions. This could potentially help in understanding the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders like schizophrenia and identify novel antipsychotic treatment.

Moreover, mGluR5 tracers are diagnostic tools that could reveal their association with other motor dysfunction diseases such as LID. PET imaging with [18F]FPEB showed rapid mGluR5 uptake in the caudate–putamen region after levodopa treatment that caused abnormal involuntary movement

[3].

Although many mGluR5 receptor antagonists have been successfully used to label mGluR5 in vitro, the PET tracers have failed in vivo to meet expectations. The failure was due to high nonspecific binding, unfavourable brain uptake kinetics, and/or limited metabolic stability. For example, [18F]FPEB showed binding potential weaker than DAT tracer [11C]PE2i during PD patient brain diagnosis

[21]. It is through ushering that several mGluR5 PET tracers were made for clinical trial, namely [18F]FPEB, [18F]FPEP, [18F]SP203, [11C]MPEP, and [11C]ABP688. Yet, a few factors limit the widespread use of imaging agents of the human brain, for example, the short physical half-life of carbon-11 (t1/2 = 20 min). Among other factors, CNS PET ligands mostly depend on brain kinetics and in vivo metabolism, so the probability of success depends on these criteria improvement. So far, mGluR5 radioligands have shown their high utility in disease pathology characterisation and drug development programs. Undoubtedly, mGluR5 PET ligands are emerging targets to uncover several psychiatric and neurological diseases questions where mGluR5 is hypothetically involved.

3. Emerging Therapeutics and Prospective Targets of Group I mGluRs in PD Therapy

As mGluR1 and mGluR5 are widely expressed in the basal ganglia structures, especially at postsynaptic sites

[24], and a high expression of mGluR1 receptors can be found in the globus pallidum (GP), substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), and striatum, therefore they might be involved in PD pathogenesis. It was showed that antagonism of mGluR1 using negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) did not reduce LID in PD; only blocking of mGluR5 showed a promising reduction of dyskinesia

[25]. Some were also showed that using the mGluR5 NAMs. such as 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), mavoglurant, dipraglurant, fenobam, and 3-((2-Methyl-4-thiazolyl)ethynyl)pyridine (MTEP), were shown to ameliorate motor deficits in PD animals

[25][26][27]. Fenobam and AZD9272 have been reported to induce psychosis-like adverse events. Varnas et al. (2020) reported from a PET of the human brain that both antagonists bind to monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B), which reveals a new understanding of psychosis-like adverse effects and could generate new models for the pathophysiology of psychosis

[28]. MPEP treatment significantly ameliorated akinesia in 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced rodents and decreased LID in MPTP treated monkeys

[29][30]. Chronic treatment with MPEP in MPTP-treated PD monkeys for 1 month was found to inhibit LID

[31]. Administration of MTEP also showed a significant decrease of dyskinesia in MPTP-treated monkeys

[30] and 6-OHDA-lesioned rats

[32]. Several ones with different other NAMs such as mavoglurant

[33], dipraglurant

[34], and fenobam

[35] also reported similar anti-parkinsonism and a decrease in LID of L-DOPA in different PD models. MPEP chronic treatment was shown to attenuate DA neuronal loss and prevented microglial activation in SNpc of 6-OHDA treated or MPTP-treated rats

[36][37]. Moreover, MTEP local infusion in the striatum was reported to attenuate 6-OHDA-induced activation of ERK1/2 signalling that is associated with dyskinesia

[38]. Different antagonists of mGluR5, including AFQ056 (mavoglurant) and ADX-48621 (dipraglurant), are currently being tested in humans as anti-dyskinetic drugs. These drugs are well tolerated and have still not been reported to worsen PD motor symptoms

[39], which is encouraging and supportive to know further and develop mGluR5-related compounds as potential neuroprotective drugs in PD.

3.1. Regulation of Autophagy

Group I mGluRs are potential regulators of several autophagic signal transducers that contribute to the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and HD. However, the role of members of this mGluR group has not been evaluated yet in the PD model; hence, it was prospected a few potential targets that might interest mGluR-mediated autophagy-based therapeutic development. Optineurin is a multifunctional cellular network processor protein that regulates membrane trafficking, inflammatory response, and autophagy, and mGluR5-mediated autophagic signalling is regulated by optineurin

[40]. mGluR5 couples to canonical Gαq/11 and activates autophagic machinery via mTOR/ULK1 and GSK3β/ZBTB16 pathways. In this process, mGluR5 promotes intracellular Ca

2+-influx and signals ERK1/2; interestingly, optineurin regulates mGluR5-mediated Ca

2+ and mTOR/ULK1 and GSK3β/ZBTB16 pathway activation. Although crosstalk between optineurin and mGluR5 and their contribution to neurodegenerative diseases pathology is now known

[40], downstream signalling remains largely unknown.

In addition, long-term use of mGluR5 NAM (CTEP) attenuated caspase-3 activation, neuronal loss, and apoptosis in both heterozygous and homozygous knock-in HD mice models

[41], which occurred via activation of GSK3β/ZBTB16-mediated autophagy. Inhibition of mGluR5 attenuates autophagosome biogenesis-related kinase ULK1 and increases autophagy factor ATG13 and Beclin1. In addition, inhibition of mGluR5 by CTEP reduces aberrant phosphorylation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling cascade

[42] that promotes ULK1 activity and autophagy. Antagonism of mGluR5 via selective NAM (CTEP) promotes aggregated protein clearance by autophagy activation and facilitates CREB-mediated BDNF expression in the brain, fostering neuronal survival and reducing apoptosis. In addition, chronic use of CTEP for 24 weeks was shown to reduce the Aβ burden in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mouse hippocampus and cortex; however, CTEP at 36 weeks became ineffective

[43]. Reflecting that mutation at APP in the advanced disease stage could alter mGluR5 expression and mGluR5-mediated ZBTB16 and mTOR signalling in the brain. Inhibition of mGluR5 and subsequent mTOR phosphorylation could also alleviate inflammatory responses by decreasing IL-1β expression that might have been correlated with the activation of autophagy

[44].

3.2. Gut-Brain Axis

Braak et al. (2003)

[45] postulated that αS pathology could spread from gut to brain, and that the vagus nerve plays an essential role in this process. It was showed that αS injection at the duodenum and pyloric muscularis layer led to αS accumulation at the dorsal motor nucleus and later spread in caudal portions of the hindbrain, locus coeruleus, basolateral amygdala, and SNpc

[46]. mGluR5 antagonism (by MPEP) significantly affects peripheral afferent ending gastric vagal circuitry

[46]. Thus, suppressing primary sensory endings via mGluR5 antagonist could rescue them from αS-pathy and associated neurodegeneration and behavioural deficits.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines10040864