Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Recently, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of many types of tumors including breast cancer have emerged as a powerful tool for predicting drug efficacy and for understanding tumor characteristics. PDXs are established by the direct transfer of human tumors into highly immunodeficient mice and then maintained by passaging from mouse to mouse. The ability of PDX models to maintain the original features of patient tumors and to reflect drug sensitivity has greatly improved both basic and clinical study outcomes.

- Patient-derived xenograft (PDX)

- breast cancer

- precision medicine

- clinical trial

- drug development

- tumor biology

- mouse model

- immune system

- HER2 positive subtype

- hormone positive subtype

- triple negative subtype

1. Patient-Derived Xenograft Models of Each Breast Cancer Subtype

1.1. Luminal A and Luminal B Subtypes

Most tumors of these subtypes are efficiently treated by therapeutic strategies targeting ER and estrogen production [1], suggesting that they are strongly dependent on the function of estrogen. Therefore, estrogen pellets are often injected into immunodeficient mice before tumor transplantation when producing luminal-type patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models [2][3][4]. Kabos et al. showed that the xenografts derived from luminal tumor expressed ER at a similar level to patient tumors of origin [3]. This indicated that the dependency on estrogen did not change after transplantation. Another report using luminal subtype PDX models for pre-clinical purpose made it clear that the B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) Homology 3 (BH3) mimetic improved the tumor response to the antiestrogen tamoxifen [5].

1.2. HER2 Positive Subtype

HER2 positive subtype tumors show relatively low take rates, and the number of therapeutic studies using this type of PDX is limited. However, Kang et al. successfully utilized this model and showed that WW-binding protein 2 (WBP2) helped the inhibitory effect of trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting HER271. They suggested that WBP2 would be useful as a companion diagnostic for the management of HER2 positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-based therapies. In addition, PDX models of HER2 positive breast cancer-derived brain metastases were also developed by Ni et al. [6]. By using these PDX models, they found that the combined inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) led to the durable regression of metastasized tumors. The brain-metastasized models of this type of tumor also resembled the parental metastasized tumors of patients histologically, highlighting the ability of PDX models to maintain original features.

1.3. Triple Negative Subtype

This type of breast tumors does not express ER, PR, or HER2. Therefore, they cannot be treated with endocrine therapy or anti-HER2 targeting strategies. The triple negative subtype represents about 15–20% of breast cancer patients and shows the worst prognosis of the major four subtypes due to the lack of effective treatment other than cytotoxic chemotherapy [7][8]. Therefore, the development of new therapeutic strategies is urgently needed. PDX models of triple negative breast cancers are often utilized for such a purpose [9][10][11]. One reason for their popularity is that, in all the subtypes of breast cancer, the triple negative type shows the highest take rate, partly because of its strong aggressiveness [12][13].

Research using a triple negative breast PDX by EI Ayachi et al. showed that the inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin/HMGA2/EZH2 signaling deprived chemo-resistance to doxorubicin in this type of tumor [14]. Based on the results, they proposed Wnt signaling network targeting therapy as a promising strategy for triple negative breast cancers. Furthermore, a pre-clinical rational for developing treatment approaches using the Notch1 monoclonal antibody [15], Wee1 kinase inhibitor [16], Wnt inhibitor [14], and so on, has been established by utilizing these PDX models.

2. Application of PDX Models for Clinical Use

PDX models are superior to cell line xenografts and genetically engineered mouse models, especially in the field of pre- and co-clinical studies, because they have much higher predictive values [17][18][19]. As long as PDXs are maintained in vivo by directly passaging from mouse to mouse, their character closely resembles that of their parental tumors for several generations. Though the take rate of first transplantation from patient to mouse varies dependent on tumor types [13][20][21][22][23], the second and subsequent take rates from mouse (or frozen stock) to mouse are generally high. Therefore, if PDXs are successfully established by first transplantation, researchers can use them for many purposes by passaging formed tumors to a larger number of mice.

2.1. PDX Models for Drug Development

A very large number of novel drug candidates drops in phase Ⅱ of clinical trials, which is the cause of the enormous costs needed for drug development. The major reason for this problem is the poor predictive values of current cancer models (cell line xenograft or genetically engineered mouse) used in pre-clinical studies. PDX models have the potency to improve such a situation by enabling researchers to predict drug efficacy more precisely [24], as suggested by Zhang et al. [2]. Karamboulas et al. established a large collection of PDX models of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). They showed the efficacy of CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors for HNSCC with CCND1 and CDKN2A genomic alterations [25][26]. For breast cancer, Grunewald et al. evaluated the activity of a novel fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitor, rogaratinib, using cancer cell lines and breast cancer PDX models [27]. They found that the inhibitor has a strong efficacy for FGFR overexpressing cells, both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, based on these findings, they started clinical trials of rogaratinib for patients with FGFR overexpressing tumors.

2.2. PDX Models for Precision Medicine

Making appropriate therapeutic regimes based on the features of each tumor leads to better treatment responses. Breast cancers are categorized based on the expression levels of ER, PR, and HER2, and many patients have benefitted from the therapeutic strategies developed according to these categorizations. On the other hand, patients with triple negative subtype tumors show a worse prognosis due to the lack of the good therapeutic targets [28]. In order to improve this situation, researchers are trying to further divide triple negative types into some detailed subtypes, such as basal-like 1, basal-like 2, mesenchymal, and luminal androgen receptor [29][30]. PDX models in drug screening tests will accelerate these studies by enabling us to predict drug efficacy on each triple negative tumor subtype.

2.3. PDX Models for Co-Clinical Trials

In order to determine appropriate therapeutic strategies for each patient, co-clinical trials using mouse models are parallelly operated with clinical treatments [31][32]. Originally, genetically engineered mouse models that had the similar genetic abnormalities to patients were used for this purpose [33][34][35]. However, to predict drug efficacy more precisely, PDX models are being used more these days. For some tumor types, including ovarian cancer and head and neck sarcomas, studies to confirm the efficacy of PDX co-clinical trials are now ongoing. Though some reports, including one by Julic et al., support this concept, there are many hurdles that must be crossed to use breast cancer PDX models for co-clinical trials. Firstly, the take rates of breast cancer are very low, which makes breast cancer PDX models unreliable for therapeutic options. Secondly, it takes a long time (3 months–1 year) to establish the model, which could cause delays to determining therapeutic strategies.

3. Limitations of Current PDX Models

3.1. Lack of Immune Cells

In many types of tumors, including breast cancer, immune cells in tumor microenvironments play very important roles for tumor growth and progression [36][37]. However, current PDX models are established by transplanting tumors into highly immunodeficient mice, which lack the majority of an immune system required in order to obtain higher take rates. Therefore, PDX models cannot reproduce the interaction between cancer cells (or other microenvironment components) and immune cells which exist in patient tumors. This may make it difficult to completely predict drug efficacy and to understand drug resistance mechanisms [38][39]. Fortunately, as described later, next generation PDX models have been established to overcome this kind of limitation.

3.2. Low Take Rates

The take rates of transplanted tumors greatly differ among tumor types of origin. In general, the take rates of patient derived breast cancers are very low (approximately 10–25% on average) [13][40], although the development of pre-exposure methods of estrogen has slightly enhanced the take rates of luminal type tumors. The low take rates and long term incubation periods in transplanted mice make it difficult for us to utilize breast PDX models for pre- or co-clinical studies. If further studies develop more suitable mice for PDX models or better methods of tumor transplantation, which contribute to higher rates of breast tumors, breast cancer PDX models will be more popular in clinical studies.

3.3. High Cost

The financial aspect should also be taken into consideration, because highly immunodeficient mice are very expensive. Maintaining those mice in a clean environment also takes a high cost, as it takes long time before tumors are engrafted and begin to grow in PDX models.

In the case of co-clinical trials using PDX models, a whole genome analysis of original tumors will also be needed. There are still some problems to be solved before PDX models show their true value in clinical settings.

4. Next Generation PDX Models with Human Immune System

It has become clear in the last few decades that components of the tumor microenvironment play very important roles for cancer cell growth and maintenance [41]. The tumor microenvironment is composed of very heterogeneous populations: Cancer cells, cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs), vascular epithelial cells, many kinds of immune cells, and platelets [42]. In order to reproduce more accurate conditions of tumor origins, much progress has been made in PDX establishment methods. One example is to transplant patient-derived CAFs or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), along with cancer cells, to recapitulate the interaction between cancer cells and CAFs [43].

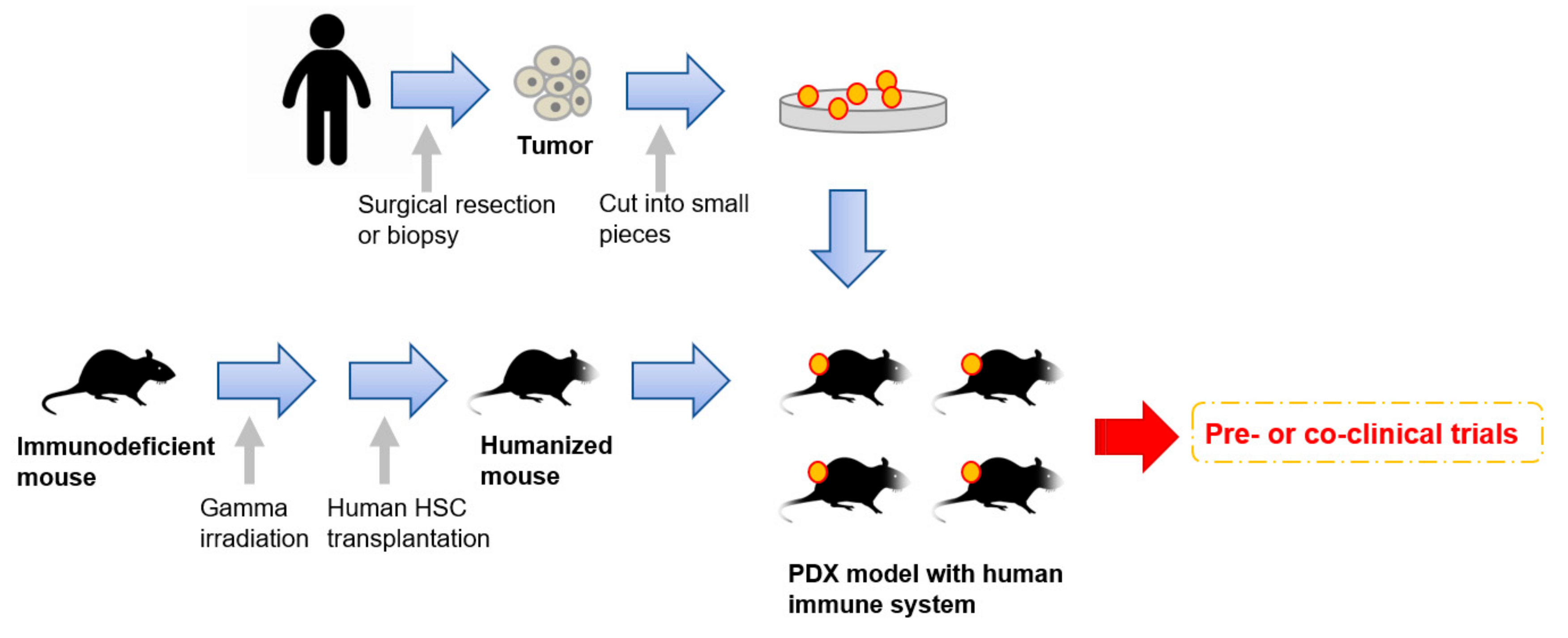

Very recently, humanized mice have started to gather attention as an attractive tool for PDX models [44][45][46] (Figure 1). To enhance the take rates of patient derived tumors, highly immunodeficient mice have been widely used for PDX model establishment. However, mice lacking an immune system cannot recapitulate the interaction between cancer cells and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. To overcome this disadvantage, mice engrafted with a human immune system are expected to be a promising tool for the next generation PDX models. In 2008, Pearson et al. suggested a protocol for the generation of humanized mice with human immune cells [47]. Adult immune deficient mice like NSG mice are irradiated by 240 cGy whole body gamma irradiation. After four hours, T-cell depleted hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) containing CD34+ cells are injected into the lateral tail vein. Then, human HSCs are engrafted in the immune deficient mice 10 to 12 weeks after injection [47]. Rosato et al. established triple negative breast cancer PDX models with these humanized mice [44] and provided the evidence supporting the use of humanized PDX models as good models for the pre-clinical investigation of immune-based therapies. In addition to immune-based therapies, humanized PDX models will also improve the predictive values for other types of therapeutic strategies.

Figure 1. An overall procedure for the generation of PDX models engrafted with a human immune system. Humanized mice are generated by a human hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) transplantation into irradiated immunodeficient mice. Patient-derived tumors obtained by surgical resection or biopsy are sliced into small pieces and then transplanted into the humanized mice.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells8060621

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!