Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Energy & Fuels

Thermal adaptation is a design strategy and lifestyle matter that makes building users central and effective towards an environmentally friendly energy transition.

- rebound effect

- passive design

- thermal zoning

- occupant behavior

- energy sufficiency

- affluence

Dear author, the following contents are excerpts from your papers. They are editable.

Thermal adaptation is an old bioclimatic design principle that was found in vernacular and traditional architecture. Instead of installing a mechanical system for heating or cooling, occupants and the buildings acted as the thermal system [1]. Thermal adaptation is a design principle that involves two main strategies. The first strategy involves spatial thermal zoning; in other words, compartmentalization. Thermal zoning allows the temporal use of spaces depending on comfort needs. A building is divided into separate thermal zones where occupants can select the most comfortable zone and control the comfort conditions through passive or/and active systems [2]. Careful thermal zoning effectively reduces the heating or cooling energy demand in the occupied spaces [3]. The second strategy involves occupant behavioral changes and traditions. People will adapt their occupancy patterns and comfort expectations depending on the season and engage in social and cultural practices that improve the thermal quality of occupied spaces. Behavioral habits and activities such as gathering, eating, changing clothes, opening windows, etc., will be adapted, concentrated, and localized depending on the availability of heating or cooling energy sources [4]. Thus, vernacular architecture worldwide displays a remarkable understanding and adoption of the thermal adaptation principle [5].

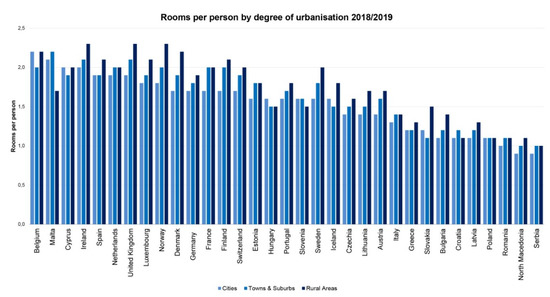

Today, with the use of Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems in most buildings, the energy-use intensity exceeds most energy efficiency standards requirements. Scientists and construction professionals are engaged in closing the energy performance gap and increase the energy efficiency of renovated and newly constructed buildings [6]. The same applies to high-performance buildings, including Passive House (PH) certified buildings and nearly- and net-zero energy buildings. At the same time, another trend influences building energy-use reduction targets. Average homes are becoming more spacious, and the floor area is increasing by roughly 3% per year, which is a remarkably faster rate [7]. As shown in Figure 1, the rooms per person are significantly high. According to Eurostat, most EU countries have increased the number of rooms per person since 1990 [8,9].

Belgium is topping the list at 2.2 rooms per capita, which is equivalent to 70 square meters. Despite the significant energy-use intensity decrease in renovated and newly constructed households, the overall energy use of the building sector remains high. Belgium is one of the earliest countries in the EU Zone that introduced nearly- and net-zero energy building (nZEB and NZEB) concepts [10]. However, the highest income earners live in recently built or renovated housing that is large, which tends to improve the energy efficiency per square meter but increases the total energy use per capita [11]. The increasing trend of the higher building energy footprint of a high-income individual is not only found in Belgium but can be found worldwide [12].

Despite the improvements in the energy efficiency of high-performance buildings, the study of occupants’ thermal adaptation and behavior remains mostly unaddressed, private, and scientifically not studied. The work of the International Energy Agency (IEA), namely Annex 66 and Annex 79, on occupant behavior in buildings, remains technology-driven, academic, and does not address the design strategies of spatial and behavioral thermal adaptation [13]. There is a gap between the expected energy use in newly built and constructed buildings and the real energy use [14]. The energy efficiency measures introduced in the building sector do not necessarily reduce total energy consumption. Sustainability is founded on the Trias Energetica principles that seek to limit energy use, use renewable energy sources, and make efficient use of fossil energy resources [15]. Thus, the concept is based on the continuous resource efficiency improvements due to technological progress. However, there is an overestimation of the potential saving effects due to efficiency improvements due to ignoring the behavioral responses of building users evoked by technological enhancements [16]. Several empirical studies from the 1990s and 2000s confirm the existence of the so-called “rebound effect” concerning improvements of energy efficiency in heating systems and insulation. The rebound effect of energy use is mainly due to thermal comfort standardization and the improvement of well-being [17]. Besides, the demographic transitions of the last 30 years, which led to the proliferation of bedrooms and home-based activities, have increased the expectations of privacy and personal space [18] in households. The property boom and real estate speculations were encouraged by many national taxation schemes, increasing the overall occupied surface area per capita worldwide.

These factors highlight the remarkable influence of the behavioral responses evoked by efficiency increases and their considerable impact on energy use in renovated and newly constructed buildings.

Several studies evaluated the real energy performance and indoor thermal comfort of modern buildings before and after renovation. The study by Hens warned the scientific community about the overestimation of the real end-use savings of passive house and zeros energy buildings. It referred to the implications of the rebound effect [19]. Bourelle identified the potential contributors to the rebound effect in net-zero energy buildings [20]. Similarly did Rovers by warning about the lost energy saving potential in zero energy buildings due to rebound effects such as more heated space, higher comfort temperature, and a more extended heating period [21]. Ferreira et al. assessed the benefits of renovation with a nearly-zero energy target for six buildings from Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden. In their study associated with the IEA EBC Annex 56 project, they addressed policymakers and explained that promoting energy efficiency does not lead, by default, to significant energy savings [22]. However, they highlighted the social benefits of high-performance buildings such as health or fuel poverty eradication. Next, Hamburg presented a five-story nZEB renovation and showed that occupants affect energy performance goals [23]. Several reasons did not allow the nZEB performance targets to be met directly related to occupant comfort expectations [24]. Considering this overview of the literature, few studies focused on assessing the real performance of high-performance buildings concerning the rebound effect concerning thermal adaptation. This lack of knowledge highlights the importance of qualitative and quantitative post-occupancy evaluations to characterize the rebound effect impacts and the spatial and behavioral thermal adaptation of occupants in newly renovated buildings.

Therefore, this study aims to promote energy sufficiency through thermal adaptation. The objectives of the study are to (1) understand occupants’ thermal behavior in nearly- and net-zero energy buildings, and (2) explore the presence of thermal adaptation (spatial and behavioral) strategies. The paper introduces evidence from real case studies on the presence and impact of a rebound effect in nearly zero-energy renovated households concerning thermal adaptation. The article provides valuable contributions to the new body of knowledge on high-performance buildings after three years of construction and occupation. The research methodology is based on a mixed-methods approach. A historical review of spatial and behavioral adaptation worldwide was first conducted. Then, 12 newly renovated dwellings were selected as case studies. Annual energy-use measurements of the existing homes (before and after renovation) were collected. In-depth interviews were conducted in 12 houses among people living in Brussels, Belgium. The study allowed for the conduction of this research using a mixed-methods approach and explored how people experience thermal comfort in their living environment. The study provides insights on occupants’ spatial and behavioral thermal habits and shares some learned lessons. The literature lacks insights on the influence of occupants’ thermal adaptive behavior in nearly- and net-zero energy homes; and how users can become aware of tracing the impact of their energy use and spatial exploitation of real estate. Recommendations to increase the uptake of thermal adaptation principles in design and the practice of high-performance buildings are presented.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su12197961

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!