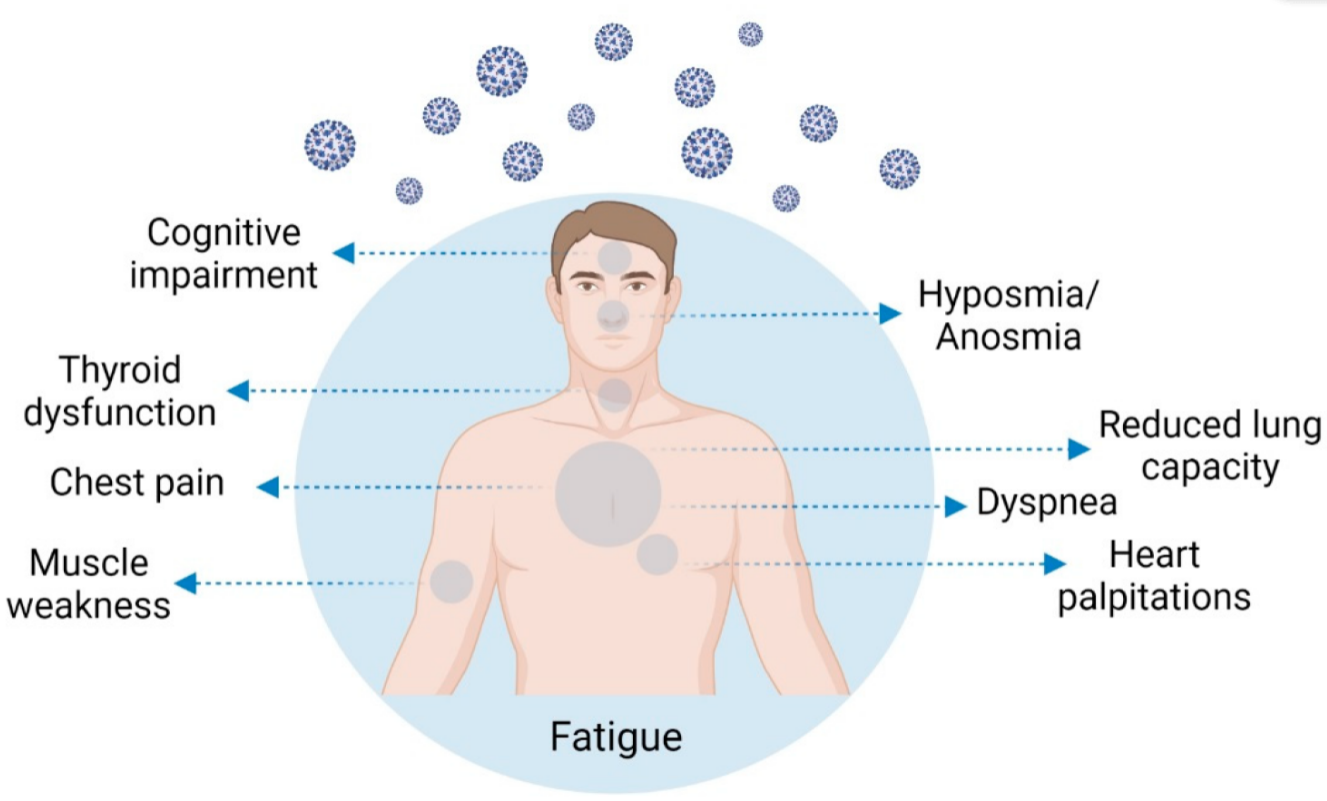

COVID-19 is currently considered a systemic infection involving multiple systems and causing chronic complications. Compared to other post-viral fatigue syndromes, these complications are wider and more intense. The most frequent symptoms are profound fatigue, dyspnea, sleep difficulties, anxiety or depression, reduced lung capacity, memory/cognitive impairment, and hyposmia/anosmia. Risk factors for this condition are severity of illness, more than five symptoms in the first week of the disease, female sex, older age, the presence of comorbidities, and a weak anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody response. Different lines of research have attempted to explain these protracted symptoms; chronic persistent inflammation, autonomic nervous system disruption, hypometabolism, and autoimmunity may play a role. Due to thyroid high ACE expression, the key molecular complex SARS-CoV-2 uses to infect the host cells, thyroid may be a target for the coronavirus infection. Thyroid dysfunction after SARS-CoV-2 infection may be a combination of numerous mechanisms, and its role in long-COVID manifestations is not yet established. The presence of post-COVID symptoms deserves recognition of COVID-19 as a cause of post-viral fatigue syndrome. It is important to recognize the affected individuals at an early stage so researchers can offer them the most adequate treatments, helping them thrive through the uncertainty of their condition.

- post-COVID-19 condition

- long COVID

- SARS-CoV-2

- thyroid

1. Introduction

2. Post-COVID-19 Condition Symptomatology and Prevalence

| Post-COVID-19 Symptoms | Number of Patients Included in the Study | % Patients Suffering from Symptom/References |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 596, 177, 538, 270, 138, 3065, 134, 242, 115, 143, 96, 1733, 5440, 384, 287 | 13.1% [34], 13.6% [20], 28.3% [7], 34.8% [25], 39.0% [27][30], 39.6% [6], 41.7% [35], 47% [26], 53.1% [36], 56.3% [28], 63% [19], up to 65% [16], 69% [37], 72.8% [38] |

| Persistent breathlessness /dyspnea | 596, 3065, 287, 270, 96, 138, 143, 384, 134, 5440, 35 | 6.0% [34], 23.2% [30], 28.2% [38], 34.0% [25], 37.5% [28], 40.0% [27], 43.4% [36], 53.0% [37], 60% [6], up to 61% [16], 80% [23] |

| Myalgia /muscle weakness | 277, 242, 134, 1733 | 19.6% [25], 35,1% [35], 51.5% [6], 63% [19] |

| Anxiety | 287, 402, 134 | 38.0% [38], 42% [39], 47.8% [6] |

| Sleep disturbance | 1733, 96, 134, 35, 138 | 21.1% [35], 26.0% [19], 26.0% [28], 35.1% [6], 40.0% [39], 46% [23], 49% [27] |

| Joint pain | 277, 143, 287 | 19.6% [25], 27.3% [36], 31.4% [38] |

| Headache | 242, 270, 3065, 287 | 19.0% [35], 19.8% [25], 23.4% [30], 28.6% [38] |

| Chest pain | 596, 242, 538, 143, 287, 35, 5440 | 0.8% [34], 10.7% [35], 12.3% [7], 21.7% [36], 28.9% [38], 34.8% [23], up to 89% [16] |

3. Post-COVID-19 Condition Risk Factors

4. Post-COVID-19 Condition Pathophysiology

Different lines of research are trying to explain these protracted symptoms. A persistent immune activation and/or inflammation may contribute to post-COVID-19 condition, which could explain why many patients with mild COVID-19 disease experience chronic persistent symptoms, involving the cardiovascular, nervous, and respiratory systems [57]. In fact, the persistently elevated inflammatory markers observed in long-COVID patients point towards chronic persistence of inflammation [18][58].

Seessle et al. [28] observed several neurocognitive symptoms that were associated with antinuclear antibody titer elevation, pointing to autoimmunity as a cofactor in the etiology of post-COVID-19 neurologic conditions [28]. The autoimmune hypothesis could explain the greater incidence of this condition in women [14][57]. Since thyroid is closely linked to T-cell-mediated autoimmunity, thyroid dysfunction may be important in the pathophysiology of post-COVID-19 condition, as discussed in more detail below [3].

Post-COVID-19 condition has been related to additional characteristics of the innate and adaptive response, involving a weaker initial inflammatory response, with lower baseline levels of C-reactive protein and ferritin [45]. The participation of the immune system in post-COVID-19 condition has been reported in other studies [8][21][57][59][60]. Symptoms such as cognitive dysfunction, persistent fatigue, muscle aches, depression, and other mental health issues are highly associated with an initial immune challenge and/or with a constant dysregulation of the immune system [29][60].

The involvement of inflammatory cytokines in the etiology of the neuropsychiatric symptoms, reported in current large-scale population-based epidemiological and genetic studies, indicates that these cytokines may have a role in the etiology of the neuropsychiatric symptoms usually observed in patients with post-COVID-19 condition [3][29][60]. This cytokine storm must also be considered as a possible driving factor for the expansion of neuropathies after severe COVID-19 infection, contributing to the chronic pain that appears after acute infection recovery [61].

Studies have shown that patients with severe symptoms may have more severe autonomic dysfunction when compared with patients presenting mild symptoms, as indicated by the heart rate variability (HRV) analysis [2], which is a reliable non-invasive tool used to evaluate autonomic modulation [2][62]. Patients with severe symptoms presenting amelioration in autonomic parameters also show enhancements in immune and coagulation functions, as well as in cardiac injury biomarkers [2].

5. Thyroid Involvement in COVID-19

Due to the reported high expression of ACE2, the thyroid may become a target of coronavirus infection, and thyroid involvement in COVID-19 patients has been demonstrated [63]. In fact, SARS-CoV-2 uses ACE2, combined with the transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), as the main molecular complex for the host cell infection [64]. Interestingly, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression levels are higher in the thyroid gland than in the lungs [64]. Scappaticcio et al. [64], in their literature review on thyroid dysfunction in COVID-19 patients, presented strong evidence that the thyroid gland and the entire hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid (HPT) axis may be important targets for SARS-CoV-2 damage.

Campi et al. [63] found a temporary situation of low TSH with normal T4 and low T3 levels in patients hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 infection, which was inversely associated with C-reactive protein, cortisol, and IL-6, and positively associated with normal Tg levels. These authors stated that this temporary change was probably due to the cytokine storm induced by the virus, with a direct or mediated impact on TSH secretion and deiodinase activity, and probably not to a destructive thyroiditis. The THYRCOV study offers early evidence that patients with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection with thyrotoxicosis have statistically significantly higher levels of IL-6 [65]. In a short-term follow-up, Pizzocaro et al. [66] showed a spontaneous normalization of thyroid function in most infected patients with SARS-CoV-2-related thyrotoxicosis. Nevertheless, these authors stated that long-lasting studies are needed, since they found a frequent thyroid hypoecogenicity pattern in the ultrasonographic evaluation of these patients, which may predispose them to late-onset thyroid dysfunction development [66].

Even though clear evidence is missing, infection of the thyrocyte, thyrotroph, and corticotroph may lead to a decrease in T3, T4, TSH, ACTH, and cortisol levels [67]. HPT dysregulation has been considered, at least in part, responsible for hypothyroidism in COVID-19 [67][68]. Low FT3 levels are independently associated with increased mortality [67][69][70] and disease severity [68][71][72][73] and may be used as a surrogate prognostic biomarker [67][69][70].

Researchers' knowledge of the thyroid patterns of COVID-19 is still incomplete, as is the etiologic view of COVID-19 and thyroid insults [67][74]. To find direct evidence concerning the nature and cause of thyroid SARS-CoV-2 injury, and the full immune response in those patients with thyroid dysfunction, researchers need a histologic and cytological examination of the thyroid gland in a wide number of patients [67][68].

6. Post-COVID-19 Condition Health Burden and Patient Management

Post-COVID-19 condition (or long COVID) first gained extensive credit among social support groups, and then in scientific and medical communities [3][5][75][76]. It is probably the first illness to be cooperatively identified by patients discovering one another using Twitter and other social media [75].

Patients with post-COVID-19 condition are a heterogeneous group, which makes it difficult to advise treatment [77][78]. It is crucial for each patient to find the correct equilibrium between mild activity to avoid deconditioning and not triggering post-exercise malaise [77]. Strategies tackling levels of stress and/or the stress response, comprising psychosocial intervention, physical exercise, or possibly dietary interventions of people could be a good approach to counteract some of the negative effects of chronic inflammation [29].

Management of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome requires a comprehensive team, including physicians of various specialties (primary care, pulmonology, cardiology, and infectious disease), physiatrists, behavioural health experts, physical and occupational therapists, and social workers, which will address the clinical and psychological aspects of the disease [79].

7. Conclusions

It is urgent to better understand this emerging, complex, and puzzling medical condition [16][80]. Post-COVID-19 condition can become a crisis for health systems, which are already facing the challenge of the pandemic [81]. The primary care services, which represent the first approach for patient diagnosis, still have little information or resources to deal with these patients [82].

There is an urgent need to identify affected individuals early so the most appropriate and efficient treatments may be provided [79][80], helping them to thrive through the uncertainty of their condition [15][83].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/life12040517