Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Environmental Sciences

Integrated Landscape Approaches (ILAs) are increasingly presented as socio-environmental conceptual frameworks for holistic management and governance of sustainable landscapes. There is a wealth of literature, case studies, and widespread international interest in ILAs to reconcile and harmonize multiple goals for conservation, development, climate change, and human well-being at the landscape level.

- integrated landscape approach

- landscape approach

- integrated landscape management

1. Introduction

Sectoral approaches to land management are proving to be inadequate for balancing socio-economic complexities and environmental demands. In the Anthropocene era [8], there is an urgent need for integration between different sectors and stakeholders goals with a long-term view, and hopefully, we have arrived in the sub-era of synergies [9]. Integrated Landscape Approaches (ILA) or Landscape Approaches (LA) (for this research, ILAs and LAs were treated as synonymous and interchangeable concepts; in the rest of the article, the term ILAs is mainly used) are increasingly presented as a conceptual framework for holistic management and governance of sustainable landscapes. There is a wealth of literature and widespread international interest about ILAs; however, “what the landscape approach means in complex social-ecological systems is subject to a wide range of differing interpretations” [10] (p. 2). In delineation from landscape-scale thinking and cross-sectoral approaches, the ILA is “framed around multifunctionality and driven by participatory transdisciplinary/cross-sectorial processes… to determine change logic and/or clarify objectives” [10] (p. 3).

ILAs are gaining international momentum, and interest is snowballing [11,12]. On current international environmental agendas, there are several initiatives to motivate and encourage the implementation of ILAs. ILAs are supported by the research community, donors, and governments; additionally, the marketability of the concept itself is acknowledged [1,12]. However, the proliferation of similar concepts, the lack of a universal definition and vagueness, the lack of consensus in conceptual schemes, and the broad challenges of sustainability itself perhaps could lead to confusion and skepticism and slow ILA implementation or leave them too open to interpretation.

1.1 Definitions of the Integrated Landscape Approach

ILAs have been given different interpretations in literature; but a consensus definition has not been reached [21] and will likely remain lacking [35]. However, a 2017 study suggested that this lack of definition might exist because the ILAs still in a developmental stage [36]. Due to the under-theorized current state of ILAs [36], other essentially similar frameworks have to be considered as nested, complementary, and even as interchangeable concepts, such as (but not restricted to) Sustainable Landscapes and Seascapes, Biocultural Landscapes, Rural Sustainable Development, Multifunctional Landscapes and Seascapes, Development Landscape Ecology, Ecology Based Approach, Territorial Approach, Jurisdictional Approaches, and Integrated Water Resource and Basin Management, among others [1,5,9,28,36,37,38]. Conceptual links between different environmental approaches are inherent to ILAs.

Unfortunately, there is little consensus about terminology, conceptual categories, and classifications for most of these concepts, not only for the ILA [29]. This lack of consensus makes ILAs particularly complicated in deployment and implementation by policy-makers [11]. Additionally, these diverse terminologies with ‘same or akin’ goals have led to a fragmentation of knowledge, confusion, and, therefore, slow progress in implementation [1,28]. According to Reed et al. [1], a study by Ecoagriculture Partners identified over 80 terms, all referring to the same idea of integrated approaches to land management. For further argumentation, seven compatible and complementary definitions of the ILA are analyzed in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of some definitions of Integrated Landscape Approaches.

| Definitions | What Is It? | Common Elements | Exceptional Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘a long-term collaborative process bringing together diverse stakeholders aiming to achieve a balance between multiple and sometimes conflicting objectives in a landscape or seascape’ [39] (p. 466). | Long-term collaborative process | Diverse stakeholders. Balance between multiple and sometimes conflicting objectives. |

Landscape or seascape. |

| ‘Integrated landscape approaches are governance strategies that attempt to reconcile multiple and conflicting land-use claims to harmonize the needs of people and the environment and establish more sustainable and equitable multi-functional landscapes’ [35] (p. 1). | Governance strategies | Reconcile multiple and conflicting land-use claims. Equitable multi-functional landscapes. |

Harmonize the needs of people and the environment. |

| ‘A landscape approach is broadly defined as a framework to integrate policy and practice for multiple land uses, within a given area, to ensure equitable and sustainable use of land while strengthening measures to mitigate and adapt to climate change. It also aims to balance competing demands on land through the implementation of adaptive and integrated management systems’ [28] (p. 1–2). | A framework | Multiple land-uses. Balance competing demands on land. Adaptive and integrated management systems. |

Mitigate and adapt to climate change. |

| ‘Landscape approaches are broadly defined as a strategy to integrate research, policy and practice for multiple land uses within a given area to enhance equitability and sustainability’ [28,40] (p. 3). | A strategy | Integrate research, policy, and practice. Multiple land-uses. Enhance equitability. |

n.d. |

| ‘A landscape approach can be defined as a framework to integrate policy and practice for multiple competing land uses through the implementation of adaptive and integrated management systems’ [1,28,36] (p. 482). | A framework | Integrate policy and practice. Multiple land-uses. Adaptive and integrated management systems. |

n.d. |

| ‘a way of achieving a balance between competing resource uses, employing multi-stakeholder interdisciplinary working modes, to sustainably meet economic, nutritional and environmental needs as well as the aspirations of people within a landscape and of those linked to it though value chains and ecosystem services’ [11] (p. 2). | A way | Balance between competing resource uses. Multistakeholder. |

Meet nutritional needs. Within a landscape and those linked to it. Value chains and ecosystem services. |

| ‘A conceptual framework whereby stakeholders in a landscape aim to reconcile competing social, economic, and environmental objectives. It provides tools and concepts for allocating and managing land to achieve social, economic, and environmental objectives in areas where agriculture, mining, and other productive land uses compete with environmental and biodiversity goals’ [41] (p. 3). | Conceptual framework | Stakeholders in a landscape. Reconcile competing social, economic and environmental objectives. |

Tools and concepts for managing lands. Areas where mining, and other compete with biodiversity goals. |

| Landscape approaches involve collaboration of stakeholders in a landscape to reconcile and optimize multiple social, economic, and environmental objectives across multiple economic sectors and land uses. Landscape approaches are implemented through processes of integrated landscape management that convene diverse stakeholders to develop and implement land-use plans, policies, projects, investments, and other interventions to advance landscape sustainability goals [42] (p. 8). | n.d. | Collaboration of stakeholders. Reconcile and optimize multiple social, economic, and environmental objectives |

Implemented through integrated landscape management. Plans, policies, projects, and investments Landscape sustainability goals. |

2. Implementation and Sustainability of ILAs

It should be noted that there are many different concepts and terminologies referred to as ILAs; therefore, their implementation could also take form in many ways. The landscape-scale should be seen as a unit of management [76]. Integrated Landscape Initiatives are those projects, programs, platforms, initiatives, or set of activities for sustainable landscape management [78]. Jurisdictional approaches are a type of ILA [83,84] with a key characteristic element: ‘the landscape is defined by policy-relevant boundaries and the underlying strategy is designed to achieve a high level of governmental involvement’ [85] (p. 3). Jurisdictional approaches, together with community-based management, independent regional community associations, biological corridors, forest/rural productive units at landscape level, jurisdictional REDD+, and integrated water resource management, are some of the most common management frameworks to implement ILAs [22,40,86]. There is clearly an urgent need to implement ILAs and use the multifaceted values of landscapes [50].

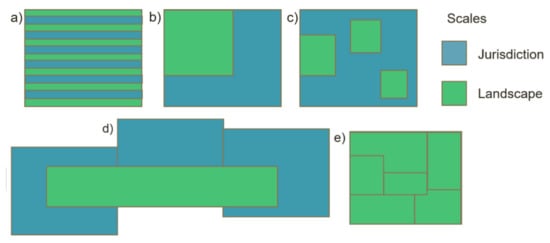

The interconnections between jurisdictional approaches and ILAs are very tight and are illustrated in Figure 1. Therefore, all individual landscapes are coordinated within the same jurisdiction, and landscapes as well as jurisdictional approaches are both implemented.

Figure 1. Interconnections between jurisdictional and landscape approaches (Source: own elaboration by authors). (a) The landscape itself is delimited within the political boundaries of the jurisdiction. The complete jurisdiction is the landscape where the landscape/jurisdictional approach is implemented. This situation is uncommon. (b) Inside the jurisdictional boundaries is one landscape where the resources to implement the approach are focused. (c) Inside the jurisdictional boundaries are two or more landscapes where the resources to implement the approach are focused. (d) The landscape touches more than one jurisdictional boundary. Therefore, the landscape approach includes a multi-jurisdictional approach for its implementation; this can be an association of multiple neighboring municipalities, states, or even countries. (b–d) and are the most common cases of landscape/jurisdictional approach implementation. (e) The complete jurisdiction is organized through a jurisdictional approach with nested landscapes or jurisdictional compacts at smaller scales, it’s a type of nested jurisdictional approach.

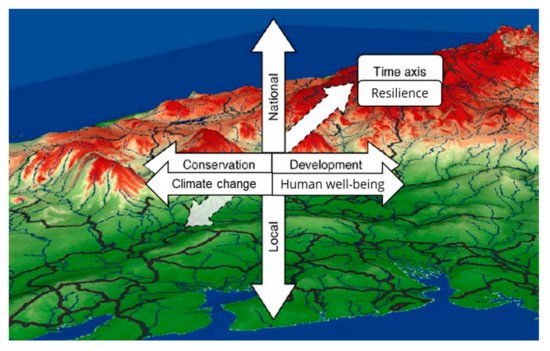

Landscapes and seascapes can be considered a socio-ecological systems. In a socio-ecological system ‘the socio refers to the human dimension in its diverse facets, including the economic, political, technological, and cultural, and the ecological to the thin layer of planet Earth where there is life, the biosphere. The biosphere is the global ecological system integrating all living beings and their relationships, humans and human actions included, as well as their dynamic interplay with the atmosphere, water cycle, biogeochemical cycles, and the dynamics of the Earth system as a whole’ [88]. Integrating governance and management in socio-ecological systems is consistent with ILAs and could therefore deliver sustainable development and sustainability outcomes at the landscape level (see Figure 2). The ILA implementation relies on landscape governance and a management plan crafted with consideration of the available natural resource-associated tools and methods for specific socio-economic needs and objectives in the landscape.

Figure 2. Integration of governance and management for ILA implementation within a socio-ecological system (Source: own elaboration by authors).

ILAs can be identified as part of the landscape concepts with the aim of sustainable development and sustainability [49,89]. In this sense, following Angelstam et al. [89], ILAs can be used as a tool to diagnose socio-ecological systems. In particular, some authors propose the use of a social–ecological network approach for developing a landscape governance framework [90]. However, good landscape governance alone cannot drive the desired landscape level outcomes; it must go hand-in-hand with the management and execution systems. The ILA implementation requires both a good and adaptive governance system in place and an adequate set of management methods and tools for the landscape context.

Landscape management is crucial to develop evidence-based governance responses that better suit to the landscape reality [54]. Landscape governance is a key element for ILA implementation, because it ‘deals with the interconnections between socially constructed spaces and the natural conditions of places’ [43] (p. 268). Findings confirm that weak landscape governance can lead to limited enforcement of the landscape management instruments. For example, this may include short-term planning and goals, corruption, unstructured collaboration, elite capture, diffuse mandates and responsibilities, sectoral and political rivalry, insufficient or inefficient stakeholder participation, high transaction cost, inadequate benefit sharing, gender asymmetries, or general policy failures regarding ecosystems and communities [2,11,18,35,37,38,91,92,93]. In order to address issues of common concern in the landscape, ILAs typically use multi-stakeholder platforms as the governance structure to set the common goals, outline a shared vision, and drive collective action [41,47]. The landscape governance’s improvement capacity will support the development of participatory theories of change that outline a shared vision and scenario building for the management plan [40]. A focus on the relationships between existing and upcoming policies is crucial to enhance good landscape governance [9].

3. Perspectives of the Integrated Landscape Approach and Sustainability

3.1. The Integrated Landscape Approach in a Challenging and Evolving World

The current times, particularly with the COVID-19 pandemic, can be recognized as a unique opportunity for humanity to innovate and transform toward a sustainable, inclusive, and climate-resilient world. In this sense, the capacity for adaptability and comprehensiveness proposed by the ILA makes it a relevant alternative to consider during these challenging times. This is due to the multipurpose benefits it can potentially achieve. The ILA shows potential to combine not only biodiversity conservation and development goals [21,47] as studies have shown, but also climate change and human well-being goals [13]. The contribution toward mitigation and adaptation goals by the ILA is not only accepted in literature [58] but is also reinforced by climate change mechanisms such as REDD+ [87], Nature-Based Solutions, and ecosystem-based adaptation [45]. Regarding the human well-being aspect, as previously discussed, this is a key element of the Landscape Sustainability theoretical framework, which is also a coherent scientific framework articulated in the ILA. The human well-being is also an undeniably consistent element of the ILA theoretical framework. Human well-being dimensions can be complex and broad in scope; however, key socio-economic and cultural aspects can be determined as relevant for the ILA, such as health, education, food security, and livelihoods [13]. Human well-being and environmental functioning are interdependent [96].

Moreover, the ILA seeks to link local needs, aspirations, and objectives with the national commitments within the specific characteristics of each landscape [21,36,39]. Nested adaptive cycles occur at specific ranges of spatiotemporal scales, and the relevance of work at a landscape-scale is rooted on the Panarchy theory, which provides the resilience (resilience is the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks [97]) component of Figure 3 [5]. In the Panarchy theory, resilience is a primary variable that controls the adaptive cycling of nested systems, where resilience is measured by the magnitude of disturbance that can be absorbed before the system changes its structure, functions, and feedbacks [98]. ILA interventions should aim to moderate adverse livelihood impacts due to climate change and aim to build the socio-ecological resilience (as stated by Folke et al., the social–ecological resilience is an approach whereby humans and nature are studied as an integrated whole, and it emphasizes that humans and well-being fundamentally rest on the capacity of the biosphere to sustain us, irrespective of whether or not people recognize this dependence [88]) capacity of the landscape inhabitants and ecosystems [86,94]. In short, the ILA is an alternative that responds to the global need for more integrative management approaches where biodiversity conservation, development, climate change, and human well-being goals can potentially be achieved at a landscape-scale in order to build resilient societies and ecosystems in the short, medium, and long term.

Figure 3. The objectives of Integrated Landscape Approaches (Source: Modified from Pfund 2010:122).

3.2. Key Barriers to Overcome

Despite the potential benefits of implementing an ILA, some barriers have been identified by Reed et al. [39], such as time lags, terminology confusion, operating silos, lacking internal/external engagement, and ineffective monitoring. Notwithstanding the international momentum of the ILA, its implementation is still perceived as risky and complex due to its abstract discourse. Nonetheless, until the ILA takes a clear shape, it will not be possible to see the underlying conflicts of interest and values around it [12]. Additionally, the ILA has been driven more by conservation and climate change goals than by development and human well-being interests [11]. This may be because most ILA scientific and international efforts are motivated by environmental goal-driven organizations. Likewise, it could be because the effectiveness of ecosystem services can be improved by ILAs [32], but it is not clear how much the ILA enhances the effectiveness of “development or production” strategies and frameworks. Indeed, when the landscape is managed, focusing on isolated efforts, these trade-offs can result in negative socio-economic and environmental outcomes [1]. However, on a landscape management or a landscape policy intervention, there will be both winners and losers [1]. Unfortunately, negotiated plans of agreed outcomes with ILAs do not necessarily avoid conflict; consequently, plans need to be adapted [38]. The question of who gains and who loses with the ILA is a central issue for sustainable development planning and design of landscapes [5,29]. Wu [5] explains that the ‘sustainability’ concept itself is more of a journey than a destination. The ILA naturally has a social and idealistic construction behind it, which might be just as significant as the journey toward sustainability itself.

3.2.1. Multi- and Transdisciplinary Academia Is as Relevant as a Cross-Sectoral Government

he ILA calls for interdisciplinary work beyond the confines of forestry science and for transformation of both forestry and foresters [24]. The ILA represents a particular challenge for transformation of forest managers and researchers; this is also confirmed by previous studies [29,104]. R. Schlaepfer and C. Elliott emphasize that forest managers need to adjust their horizons and adapt to the increasing importance of overall landscape considerations, and if they cannot, ‘they [forest managers] will continue to find their role, even with forest, being dramatically reduced’ [29] (p. 1). However, it should not be forgotten that the large number of private forest owners are also belonging to the groups affected by ILAs whose property rights have to be respected [105].

A truly great challenge is the coordination of the different local, subnational, national, and international initiatives happening at the same time within a particular geographical area or landscape, including those initiatives with similar development goals. However, during implementation, there may be disorder on the ground, which results in uncoordinated projects and sectoral policy implementation. This sectorization of the government coincides with sectorization in academia. Even at a global level, the sectorization of UN agencies is evident and coordination between research efforts for climate change, biodiversity, food, forestry, and water, among others, is often lacking. Fields of research still deeply separated [29,89], so integral and holistic approaches are not only a governmental job but are also a responsibility for academia. At the landscape level, the Landscape Sustainability and Landscape Ecology sciences are trying to accomplish this. However, the necessity for multi- and transdisciplinary work is also emphasized by scholars of forestry, biodiversity, agriculture, sociology, anthropology, economy, and many other natural resources, engineering, and human and social sciences [1,5,18,29].

Since sustainable development [110] and climate change are some of the biggest challenges of the current age, governmental as well as non-governmental actors must be involved. Multi- and transdisciplinary work by academia can provide knowledge for governments, private enterprises, UN agencies, and donors. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge the multiple sources of knowledge needed for driving successful ILA implementation, including the integration of Western science with indigenous, traditional, and local knowledge systems [58] and the knowledge that different stakeholders provide to researchers and science [45,54]. According to Angelstam et al., 2013 [72] (p. 117), not only do the ‘borders of academic disciplines need to become more porous’ but also ‘academic and non-academic actors need to collaborate using both quantitative and qualitative methods’. The applications of tools for scenario building and theory of change, as well as mixed-methods for socio-environmental analyses, are fundamental for transdisciplinary research advancement of ILAs [35].

Studies reveal the importance of recognizing the value of ‘design-in-science’ or ‘research for/on/through design’ paradigms in order to ultimately transfer and apply knowledge to society [5,111,112]. Regarding the ILA, the linkage between science and practice (or landscape change) is ‘landscape design’, and the ‘design’ aspect for ILA has been poorly developed in today’s scientific research [111,112]. Additionally, Cumming et al. [3] explain the interactions between theory, models, and empirical data, where models act as a mediator between empirical data and the development of theory (as well as concepts). ILA simulation models, as well as agent-based models, can provide key information to further inform the theory and provide insights of the trade-offs in the landscape system [54].

In a similar way, recent developments in participatory scenario planning and systematic conservation planning methodologies may support research and assessment of ILA initiatives [113,114,115]. Such exercises explicitly acknowledge the interactions of several stakeholders, contesting values, and human activities that can be appraised, analysed, and negotiated in participatory landscape scenarios [116]. Within these methodologies, the values and voices of all stakeholders can be considered in the planning and design of sustainable landscapes, thus improving the legitimacy of policies and strengthening landscape governance [77]. A multi- and transdisciplinary approach that engages multiple stakeholders and sectors can directly contribute to the management and action plans of the landscape and the subsequent long-term monitoring studies [54].

3.2.2. Exercising Long-Term Thinking for Sustainability

For sustainability implementation, and for the ILA, short-term initiatives have proven to have a shallow impact; a long-term commitment is required to achieve results at scale [38,89]. Studies recommend the assurance of at least ten years of investment in order to properly establish a landscape approach [11]. However, how long is long-term for sustainability? Wu [5] (p. 1014) helps answer this question and specifies that ‘‘long-term encapsulates a timeframe of a few to several generations (decades to a century), in general”. Therefore, long-term for sustainability and for sustainable development may mean considering up to 100 years. In practice, long-term planning may mean inter-generational thinking, which is not an easy task, especially for politicians. To consider a 100-year period would mean societies from 1921 would have needed to consider today’s current needs and should have guaranteed that these needs could be satisfied. Similarly, what will human societies need in 2121, so that it can be guaranteed that those needs can be met? It is impossible to accurately predict what human life will be like in 2121, but it is likely that the humans of 2121 will still need natural resources to produce products and satisfy their needs. Thus, it is still relevant to invest in sustainable strategies and initiatives with short, medium, and long-term planning. A very well-illustrated case of this type of planning is the city of North Vancouver in Canada. In 2009, the city published their “100 years sustainability vision” [117], an innovative plan that is worthy of further attention from governments, stakeholders, and researchers.

A helpful tool for long-term planning is the incorporation of a systematic adaptive management approach or adaptive collaborative management to assure an iterative and flexible process [1,29,38,47]. Paradoxically, the adaptive management approach was the worst-performing criterion in all the ILA initiatives analyzed in a study in Mexico [22]. This may be because most of the ILA initiatives contemplate a short–medium term planning framework that often lacks capacity for addressing long-term objectives.

Ultimately, local landscape stakeholders are the key to supporting long-term landscape thinking. Stakeholders who are directly concerned with and impacted by the landscape need to be able to take ownership and commitment to implement and assess the progress of the short–medium and long-term goals of the ILA that they themselves helped to establish [54]. Landscape change is related to people’s expectations, preferences, and general relationship with the landscape [118]. The results of a 20-year study made by Palang et al. [118] in Estonia conclude that the stronger people’s identity and connection with the landscape, the more people care for and provide stewardship to that landscape, and that the best ecologically preserved landscapes are usually the ones that people care about the most.

Another useful tool that may support the ILA to incorporate long-term scales in planning and design is the modeling of scenarios. Several methodologies and software now exist that are designed to build landscape scenarios; with participation of relevant stakeholders, these can help to anticipate trends and future trajectories in the dynamics of ecological and human processes [115,119,120]. For example, different management decisions and interventions can be assessed in order to compare system behavior and identify the best outcomes in the long term [114,121]. These modeling exercises may take into consideration not only the environmental variables, but also the social, political, and economic variables. Such exercises can be applied to spatial and temporal scales to learn from modeling the dynamics of ILAs in different contexts and scenarios, such as global change. Scientists also recommend the platform Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research (LTSER) to generate and share knowledge on long-term and place-based (including landscape) sustainability [122].

Long-term thinking at the landscape level requires envisioning the future of the landscape, and envisioning the future of a landscape requires an open-minded view, as well as the analysis of past and present events and experiences. Failure to consider historically legitimate interest by stakeholders results in the inability to manage the present-day landscape and the current distribution of ecosystem services [123]. Additionally, present and future ecological research will benefit from robust data on historical climate, forest cover, biodiversity, or fire prevalence in the landscape [54]. In order to study the management of historical cultural landscapes, researchers suggest using approaches of path dependency theory, cultural sustainability, and cultural ecosystem services [118].

The foundation of sustainability requires that present needs be met without compromising the needs of future generations. Hence, to achieve overall sustainability in landscape interventions, it is key to embrace the complexity and benefits of long-term planning and long-term thinking. The temporal scale is also part of the spatial transformations in societies and ecosystems, such as explained in the Panarchy theory of adaptive cycle and foundation theory on landscape sustainability science [5,98].

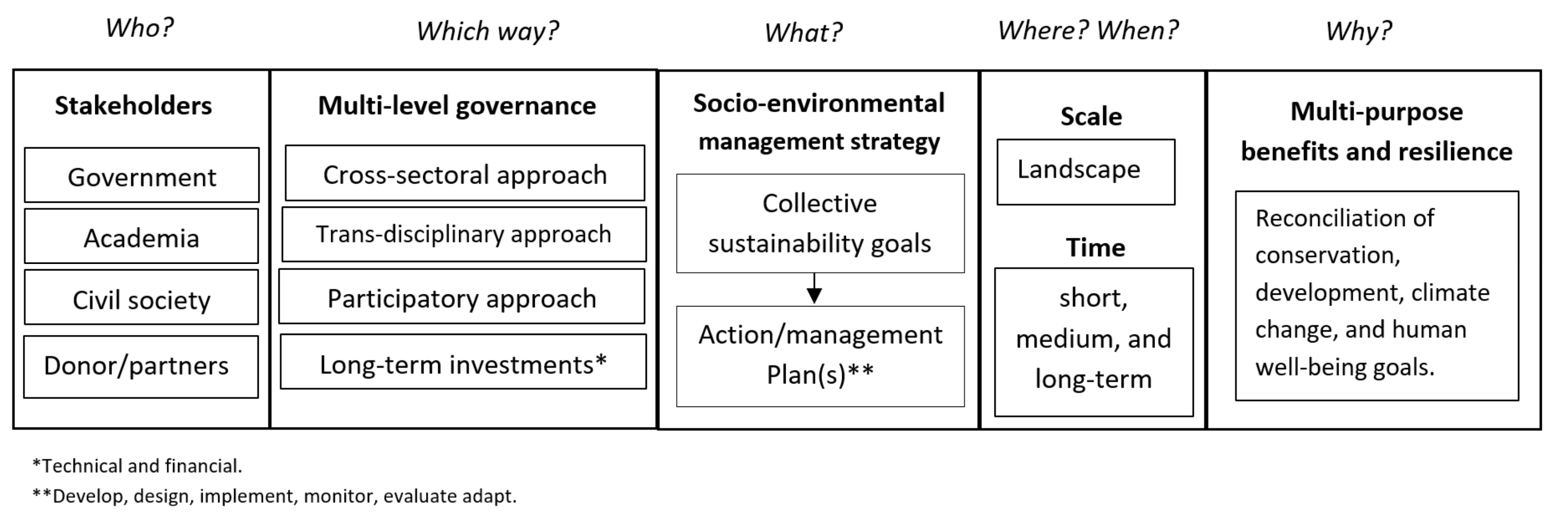

Figure 4 presents a summary of the ILA by answering the Six W’s of the ILA.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/f13020312

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!