Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Oncology

The incidence of non-viral causes of hepatocellular carcinoma, such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), is rising. The introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) has led to a paradigm shift in the systemic treatment of HCC. However, not all patients can benefit from ICI. Studies have suggested that the response to ICI may allude to the underlying aetiology of HCC, such as NASH.

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- NASH-HCC

- immune checkpoint inhibitors

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a global healthcare challenge with increasing incidence and mortality [1,2]. HCC is the sixth-most-common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer mortality globally in 2020, resulting in more than 900,000 new cases and 830,000 deaths [1]. The major risk factors for HCC include chronic viral infection (e.g., hepatitis B, hepatitis C), metabolic syndromes (e.g., type 2 diabetes, obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), NASH) and its related lifestyle (e.g., smoking). While the incidence of viral HCC has declined due to the widespread vaccination program and increased public awareness, the incidence of NAFLD/NASH-HCC has risen steadily, possibly due to the changing prevalence of obesity and diabetes [2].

2. Immune Surveillance, Immune Microenvironment, and the Immune Checkpoints

2.1. Immunoediting

The concept of immune surveillance can be traced back to more than a centennial ago. In 1909, Paul Ehrlich formulated the hypothesis that the human body constantly generated neoplastic cells that could be eradicated by the immune system [32]. However, this was not proven due to inadequate knowledge and experimental tools. In the 1960s and 1970s, Lewis Thomas and Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet independently proposed what has presently become the foundation of the theory of immune surveillance. They stated that tumour-associated antigens can be recognised and targeted by the immune system to prevent carcinogenesis, similarly to graft rejections [33]. This concept was supported by experiments in the mouse model, demonstrating that genetically identical mice could be immunised against transplants of syngeneic tumour cells [34]. In 2002, Dunn et al. proposed a refinement of the concept of immune surveillance, called ‘immunoediting’, which could be classified into three phases: elimination, equilibrium, and escape [35]. In the elimination phase, cancer cells with tumour-associated antigens are recognised by the immune system and are eliminated. The equilibrium phase is the intermediate step, in which the immune system iteratively selects and promotes the generation of tumour cell variants with increasing capacities to evade immune surveillance. In this phase, tumour cell growth is still under control. In the final escape phase, it is characterised by uncontrolled tumour growth, due to the survival advantage sculpted by the immune system in an immunocompetent host [35].

2.2. The Immune Microenvironment in the Liver

It is important to understand that the pathogenesis of HCC, regardless of the underlying aetiology, stems from chronic inflammation. It is essential to recognise that the immune microenvironment in the liver is distinctive to other organs, in order to prioritise biomarkers for drug development and treatment strategies. The liver has a unique blood supply, with the hepatic arterial blood joining the portal venous blood and draining into the hepatic veins, within a structure called the liver sinusoid. A large spectrum of microbes, microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) continuously shower the liver sinusoids from the gut through the portal blood [36]. While these foreign molecules are constantly recognised and removed by tissue residential immune cells, such as the Kupffer cells (KCs), immunotolerance is maintained through the intricate interactions between the basal pro-inflammatory molecules (e.g., IL-2, IL-7, IL-12, IL-15 and IFN-γ) produced by the hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), NK cells, NKT-cells and γδ T-cells, and counter-balanced by anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, IL-13, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β)) produced by the myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), regulatory T-cells (Tregs), liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) and KCs [37,38].

Under conditions of chronic inflammation, this balance is lost and tips towards the pro-inflammatory state, resulting in increased hepatocytes turnover, compensatory proliferation, acquisition of mutations and malignant changes [38]. Eventually, HCC develops under the background of exhausted and dysfunctional effector cytotoxic T-cells. This is accompanied by the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment, which is bathed with tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs), Tregs and MDSCs.

Comprehensive multiomics and single-cell analyses of human HCC tissues provided support of the presence of immunosuppressive cell populations in the tumour microenvironment, which fostered the growth of HCC [39,40]. Amongst them, TAMs are the most well studied. TAMs consist of KCs and blood/bone borne monocyte-derived macrophages. TAMs promote HCC progression in several ways, including the secretion of IL-10 and other immunosuppressive cytokines, promotion of angiogenesis, recruitment of Tregs and IL-17-expressing CD4+ T helper 17 cells, expression of inhibitory immune-checkpoint ligand PD-L1 and induction of proliferation signalling pathways [16,38,41]. Together with a high number of MDSCs residing in the liver, which secrete immunosuppressive molecules, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TGF-β and arginase that suppress T-cells activation [38], a strong immunosuppressive milieu is created, leading to immune escape and enabling uncontrolled tumour growth (Figure 1).

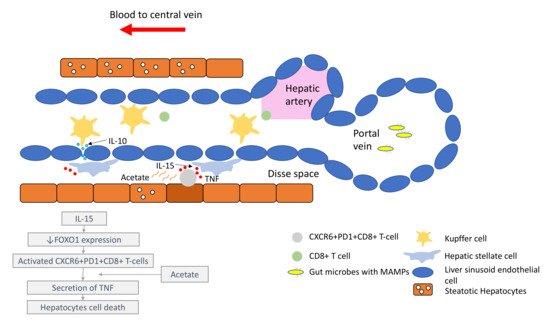

Figure 1. Liver immune microenvironment in NASH patients. In NASH patients, liver immune tolerance is lost and tips towards pro-inflammation. The IL-15 triggers decreased FOXO1 expression and activates the residential CD8+PD1+ T-cells. These residential T-cells, upon encounter with the acetate secreted by steatotic hepatocytes, release TNF, which triggers hepatocyte cell death through a FAS–ligand-dependent manner. This process is thought to bring about the NASH to NASH-HCC transition.

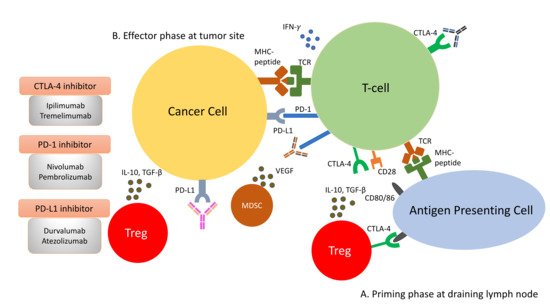

2.3. The Immune Checkpoints, CTLA-4 and PD-1

Amongst the most studied immune checkpoints to date are CTLA-4 and PD-1 [42,43]. These immune checkpoints have been successfully targeted by drugs to restore immunosurveillance for tumour cell killing. CTLA-4 is a negative regulator of T-cell activity. It acts in the priming phase in the draining lymph nodes, where T-cell activation takes place [44]. T-cell activation requires two signals: the first signal occurs when the naïve T-cells encounter their cognate antigen presented by the antigen-presenting cells on their MHC molecule. This activates T-cells but is inadequate to maintain their activation unless a second signal is provided. The second signal is provided by the CD80/86 molecules on the antigen-presenting cells and the CD28 molecules on naïve T-cells. This second signal lowers the threshold of T-cell activation significantly and enables T-cells to differentiate and engage in clearing foreign antigens, such as bacteria or tumour cells. Once the T-cells become activated, they begin to express an inhibitory molecule to tamper down the immune response to avoid overactivity. This is achieved by CTLA-4’s higher affinity for CD80/86 than CD28, impairing effective T-cell activation. Furthermore, CTLA-4 is constitutively expressed on Tregs and thus plays an essential role in maintaining the immunosuppressive environment within the tumour microenvironment [45]. Consequently, the ICI targeting CTLA-4 aims to reinvigorate T-cell activation to counteract the ability of tumour cells to escape immunosurveillance.

As opposed to CTLA-4, PD-1 is a negative regulator at the effector phase of T-cell activity at the tumour site [44]. It is an immune inhibitory receptor expressed on activated T-cells, B-cells, NK cells and dendritic cells [46]. It has two ligands: PD-L1 and PD-L2. PD-L1 is constitutively expressed on the surface on many tissues, including the tumour cells. PD-L2 is restricted to antigen-presenting cells. Upon engagement of PD-1/PD-L1, PD-1 clusters with T-cell receptors (TCR) and transiently associates with phosphatase SHP2. These microclusters decrease the phosphorylation of downstream signalling from TCR, attenuating T-cell activation [47]. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies block the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction, enabling the reversal of T-cell anergy and restoring the anti-tumour immune response (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Immune response to tumour cells can be classified into two phases: the priming phase and effector phase (A). During priming phase, tumour antigens are detected by antigen-presenting cells, and they circulate back to lymph node to present these antigens to naïve T-cells. Naïve T-cells are activated upon encounter of its cognate antigen. A second signal is required to maintain this activation. This is mediated by the interaction of CD28 on T-cells and CD80/86 on the antigen presenting cells. When T-cells are activated, they begin to express CTLA-4 molecules, which bind to CD80/86 at higher affinity, thus removing the co-stimulation for T-cell activations and resulting in anergy (B). During effector phase, activated T-cells circulate back to the tumour site. When they encounter their cognate antigens, T-cells release cytotoxic granzymes and perforins to attack tumour cells. In addition to cytotoxic granules, T-cells also release IFN-γ, which induces PD-L1 expression on cancer cells. Binding of PD-L1 with PD-1 molecules on T-cells result in inactivation of T-cells. Apart from inactivation of T-cells from PD-1/PD-L1 interaction, the immunosuppressive milieu in the tumour microenvironment is shaped by presence of immunosuppressive cells, such as Tregs and MDSCs. They secrete immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10, VEGF and TGF-β, in the tumour microenvironment. The constitutional expression of CTLA-4 at the priming site of T-cells also plays a role in dampening T-cell activation.

3. The Paradox of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and NASH-HCC

3.1. Are NASH-HCC Poor Responders to ICI?

While the extraordinary ORR and OS offered by ICI have been heralded as the game changer in the management of advanced HCC, a recent paper published in Nature titled ‘NASH Limits Antitumour Surveillance in Immunotherapy’, has provided shocking evidence of the potential detrimental effect of ICI in NASH-HCC [31]. The study first demonstrated that the frequency of CD8+PD1+ T-cells was specifically increased in NASH-HCC in mice models. Because of these high numbers of T-cells in NASH-HCC, it was initially thought that the anti-PD-1 treatment may serve as an effective treatment. Surprisingly, when NASH-HCC mice were treated with anti-PD-1 therapy, none of the tumour regressed. Instead, there was an increased incidence of liver fibrosis and liver cancer. However, in non-NASH-HCC mice, a shrinkage of tumours was observed after anti-PD-1 therapy. These findings suggested that anti-PD-1 therapy failed to reinvigorate CT8+PD1+ T-cells to perform effective immunosurveillance. Instead, anti-PD-1 therapy promoted tissue damage and malignant changes. To further verify the function of CD8+PD1+ T-cells, the group depleted NASH-mice of CD8+PD1+ T-cells and found a significant drop in the incidence of HCC in these mice. Treating anti-PD-1 therapy prophylactically in NASH-mice increased CD8+PD1+ T-cells, aggravated liver damage and heightened the incidence of HCC. This evidence provided strong support of the carcinogenic role of CD8+PD1+ T-cells in NASH-mice.

The group took their study further to examine if similar findings could be extrapolated to human-NASH. Using single-cell RNA sequencing, they demonstrated that the CD8+PD1+ T-cells in patients with NASH shared similar gene expression patterns with those in NASH-mice. Subsequently, the group conducted a meta-analysis of three published phase III trials (CheckMate-459, KEYNOTE-240 and IMbrave150) comprising a total of 1656 patients to study the effect of immunotherapy in HCC according to the underlying aetiologies. The meta-analysis revealed that immunotherapy did not improve OS in non-viral HCC (HR: 0.92, 95%; CI: 0.77–1.11), whereas those with viral HCC derived survival benefits from immunotherapy (HR: 0.64, 95%; CI: 0.48–0.94). To isolate the effect of anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy with respect to the underlying aetiology of liver damage, the group investigated two additional small cohorts of NAFLD-HCC patients. Consistent with their hypothesis, NAFLD-HCC patients had a shortened OS after immunotherapy, as compared to patients with other aetiologies. In the first validation cohort (n = 130), the median OS was 5.4 months for NAFLD-HCC vs. 11.0 months for HCC of non-NAFLD aetiology; in the second validation cohort (n = 118), the median OS was 8.8 months vs. 17.7 months. Collectively, this study signalled a proposition that immunotherapy might not confer beneficial effects in NAFLD/NASH-HCC.

3.2. Progression from NASH to NASH-HCC

In the past few years, new knowledge has been added to our understanding on the molecular mechanisms that drive the transition from NAFLD/NASH to NASH-HCC. These findings support a parallel and multiple-hits paradigm of immune cell-hepatocyte interactions that contribute to the development NASH-HCC [56,57,58]. Firstly, CD8+ T-cells and NKT-cells were demonstrated to cooperatively induce liver damage and carcinogenesis via interaction with hepatocytes in a NASH-mouse model [58]. In addition, the metabolic activation of intrahepatic NKT-cells caused steatosis via the secretion of LIGHT. These interactions resulted in the downregulation of metabolic machinery in hepatocytes, thereby increasing oxidative stress and the activation of procarcinogenic pathways, such as LTβR and canonical NF-κB signalling, promoting a NASH-to-HCC transition [58]. Secondly, platelet aggregations as the initial inflammatory process, in the context of steatosis, were demonstrated to drive NASH to the NASH-HCC transition [59]. This phenomenon was mediated via the interactions between the platelet-specific glycoprotein Ib-α (GPIbα) with Kupffer cells. Antiplatelet therapy was demonstrated to reduce intrahepatic platelet accumulation and the frequency of platelet–immune cell interaction, attenuating NASH and NASH-related HCC in the mouse model [59]. Indeed, a recently published meta-analysis (n = 2,389,019) demonstrated that the use of aspirin was associated with significantly lower HCC risk (RR: 0.61, 95%; CI: 0.51–0.73) [60]. Thirdly, it was noted that in NASH-mice or patients with NASH, there was a distinctive group of residential CD8+ T-cells in the liver that demonstrated an auto-aggressive killing of cells in an MHC-class-I independent fashion [61]. Mechanistically, IL-15 induced FOXO-1 downregulation and CXCR6 upregulation, which together rendered liver-resident CXCR6+CD8+PD1+ T-cells susceptible to metabolic stimuli, such as the acetate released by hepatocytes with steatosis. These CXCR6+CD8+ T-cells then secreted tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and injured hepatocytes. In addition, these activated CXCR6+CD8+PD1+ T-cells caused hepatocyte cell death through a Fas ligand-dependent apoptosis. This auto-aggressive mechanism of cell killing mediated via CXCR6+CD8+PD1+ T-cells was fundamentally distinct from that by antigen presentation in protective adaptive immunity. It has been postulated that this auto-aggression of CXCR6+CD8+PD1+ T-cells in the liver is responsible for the chronic liver damage in NASH and may be implicated in the development of HCC (Figure 1).

3.3. Unresolved Questions in NASH-HCC and ICI

The meta-analysis conducted by Pfister et al. raised some important key questions [31]. Contrary to the preclinical findings of enhanced tumour progression in NASH-mice treated with ICI, the ORRs of non-viral HCC patients receiving nivolumab or pembrolizumab appeared similar to patients with viral HCC in the range of 20% [62] (Table 1). Subgroup analyses for patients treated with atezolizumab and bevacizumab demonstrated similar improvement in PFS, regardless of the underlying causes of HCC [23,24]. The favourable ORRs and PFS in the non-viral HCC patients without improvement in OS have led to several alternative hypotheses. Firstly, there was a fundamental limitation of the meta-analysis, in which it included a heterogeneous population of non-viral HCC patients. Non-viral HCC includes a wide spectrum of aetiologies, such as NASH, alcoholic steatohepatitis, cryptogenic cirrhosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and autoimmune hepatitis, etc. A lack of stratification of the underlying liver disease would make it difficult to tease out the effect of ICI on NASH-HCC. Secondly, concluding ICI was ineffective in non-viral HCC, based solely on the HR without looking at the comparator arm, is inappropriate. The control arm of the two included trials (IMbrave150 and CheckMate-459) in the meta-analysis was sorafenib. The HRs demonstrated that, relative to sorafenib, ICI demonstrated OS benefits in viral HCC but not in non-viral HCC (viral HCC—HR: 0.64 vs. non-viral HCC—HR: 0.92) [63]. It is commonly thought that non-viral HCC patients in general respond better with molecular-targeted agents (e.g., sorafenib) because they often present with favourable clinical–pathological characteristics, such as the absence of cirrhosis [64,65,66]. In particular, non-viral HCC patients treated with sorafenib demonstrated a much longer median OS compared to viral HCC in the IMbrave150 trial [23]. Therefore, the more appropriate postulation would be that the longer survival benefits of sorafenib in non-viral HCC diluted the benefits of ICI, resulting in a seeming lack of benefits of ICI in non-viral HCC. Alternatively, it could be that the survival benefits of ICI are much more pronounced in viral HCC, as observed in the Asian populations, where viral HCC is predominant [49]. Thirdly, it is uncertain whether there were differences in the access to downstream treatments in patients with non-viral HCC in the control group, which could have driven better outcomes. Fourthly, the sequence of treatments might have impacts on the outcome in patients with non-viral HCC, as observed in the management of other malignancies. In a small retrospective study evaluating 25 patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma, the treatment with immunotherapy after a BRAF inhibitor resulted in higher ORR, compared to giving immunotherapy before a BRAF inhibitor (43.8% vs. 0%). The OS, however, was not different [67]. To answer these questions, well-designed clinical trials will be needed to draw definite conclusions on the effectiveness of ICI in NASH-HCC.

Table 1. Summary of objective response rates according to underlying liver diseases in major trials.

| Study | Aetiology (Proportion) | Tx | Control | ORR (%) (Tx Arm) | ORR (%) (Control Arm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMbrave150 [23] | HBV (48%) | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | Sorafenib | 32 | 8 |

| IMbrave150 [23] | HCV (21%) | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | Sorafenib | 30 | 21 |

| IMbrave150 [23] | Non-viral (31%) | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | Sorafenib | 27 | 9 |

| CheckMate 459 [19] | HBV (31%) | Nivolumab | Sorafenib | 19 | 8 |

| CheckMate 459 [19] | HCV (23%) | Nivolumab | Sorafenib | 17 | 7 |

| CheckMate 459 [19] | Non-viral (45%) | Nivolumab | Sorafenib | 12 | 7 |

| KEYNOTE-224 [18] | HBV (21%) | Pembrolizumab | - | 24 | - |

| KEYNOTE-224 [18] | HCV (25%) | Pembrolizumab | - | 8 | - |

| KEYNOTE-224 [18] | Non-viral (55%) | Pembrolizumab | - | 30 | - |

| CheckMate 040 (dose expansion) [17] | HBV (24%) | Nivolumab | - | 14 | - |

| CheckMate 040 (dose expansion) [17] | HCV (23%) | Nivolumab | - | 20 | - |

| CheckMate 040 (dose expansion) [17] | Non-viral * (53%) | Nivolumab | - | 22 | - |

ORR: Objective response rate; Tx: Treatment; * uninfected untreated+uninfected progressor.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14061526

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!