Becker muscular dystrophy is a mild X-linked form of dystrophinopathy, with frequent cardiomyopathy.

- dystrophin,cardiomyopathy,high Ck

Definition

Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) is an X-linked recessive disorder caused by dystrophin gene mutations.

1. Introduction

Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) is an X-linked recessive disorder and has an incidence of 1 in 18,518 male births [1] and a prevalence of 0.01 in South Africa, 0.1 to 0.2 in Asia, 0.1 to 0.7 (per 10,000 males) in European countries [2]. It is caused by mutations of the DMD gene that encodes the muscle-specific dystrophin protein. The pivotal function of dystrophin is to link the cytoskeletal actin and dystrophin-associated protein complex to the extracellular matrix to stabilize the sarcolemma [3]. Some mutations of dystrophin compromise its binding at the sarcolemma and cause a specific sequence of muscle abnormalities such as muscle necrosis, altered mitochondrial metabolism, disruption of the sarcolemma, abnormality of calcium homeostasis, and reactive macrophagic inflammation [4]. The BMD typical clinical features consist of proximal muscle wasting and weakness, high creatine kinase (CK), cramps, myalgia, myoglobinuria, mild myopathy, and cardiomyopathy with fibrosis [5]. In young adults, the proximal muscle wasting and weakness are more evident at the thigh and pelvic girdle muscles and pronounced calf hypertrophy might be present [6]. At the mild end of the BMD spectrum are patients characterized by muscle hypertrophy of the calves, cramps, and elevated CK levels, but virtually no muscle wasting or weakness [7,8]. Becker muscular dystrophy differential diagnosis is important to distinguish it from other myopathies with muscle weakness; BMD patients remain ambulatory after the age of 16 years while Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) patients lose ambulation and become wheelchair-bound by age of 12 [7,9]. BMD has a later onset and is clinically less severe compared to DMD. At the molecular level. DMD gene mutations disrupt the translational reading frame, which results in complete loss of dystrophin. In BMD, the mutation maintain the reading frame and result in truncated dystrophin protein with abnormal function [7,10]. In some instances, BMD could be confused with polymyositis, an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by bilateral proximal muscle weakness. BMD can be distinguished for the presence of calf pseudohypertrophy [7,11] and frequent cardiac involvement [12].

Another muscle dystrophy group difficult to differentiate from BMD is limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, the hallmark of which is the absence of overt calf muscle pseudohypertrophy [13,14].

No definitive cure for BMD has been identified; however, steroid therapy appears useful to improve muscle function, to slow the decline of muscle strength, and to prolong in dystrophinopathy walking ability [5,15]. In recent years, a potential strategy to detect and follow dystrophic symptoms could be the use of noninvasive biomarkers to monitor the disease.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small non-coding RNAs molecules with 22 nucleotides in length that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by destabilizing the mRNA and translation silencing [16]. MiRNAs are involved in several pathological and physiological processes such as development, proliferation, differentiation, and cell death. MiRNAs are expressed in muscle and stable in biofluids, such as plasma, serum, and urine [17]. Altered levels of circulating miRNAs have been linked to several neuromuscular diseases [18].

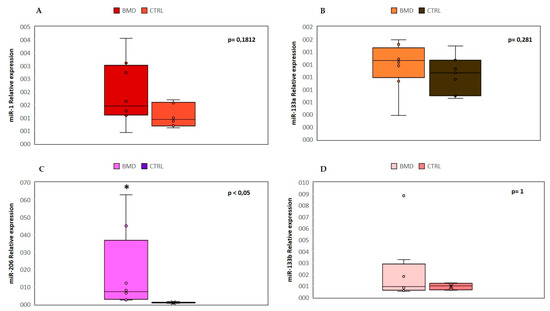

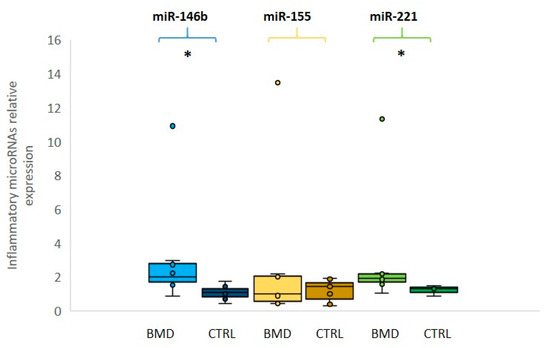

A specific group of circulating miRNAs is muscle tissue specific and they are called “myo-miRNAs” (miR-1, miR-206 and miR-133). MiR-1 and miR-133 are expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle and are involved in the proliferation and differentiation processes [19]; miR-206 is a skeletal muscle-specific miRNA expressed in satellite cells and involved in muscle development and regeneration [20]. Several studies demonstrated that the serum levels of myo-miRs are increased in DMD and BMD patients [21]. Another common feature of muscular dystrophy is the inflammatory response that triggers a cascade of inflammatory cytokines and subsequently miRNAs induction. The activation of the inflammatory system is due to the muscle injury and the subsequent macrophagic reaction, which occurs to repair the muscle damage and to promote the regeneration process. Three inflammatory miRNAs (miR-146b, miR-221 and miR-155) were found to be dysregulated in several muscular dystrophies [22].

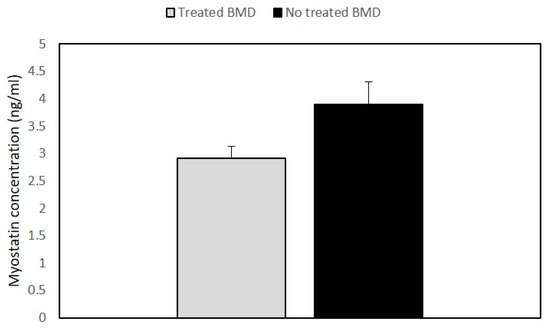

Myostatin (Mstn), also named “GDF-8,” is a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily and acts as a negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth [23]. It is known that the myostatin antagonist is follistatin (FST), a glycosylated secreted protein that controls muscle mass through different pathways [24].

2. Results

The clinical data of each patient are summarized in Table 1.

| Age at Study (Years) | Age at Onset (Years) | Deletion in the Dystrophin Gene | Dystrophin Quantity (%) and M.W. (kDa) * | Creatine Kinase Levels (U/L) | Muscle Involvement |

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction ** | Treatment and Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 42 | 5 | Exons 45–47 | 35%, 370 kDa |

1202 | HyperCKemia, waddling gait, calf hypertrophy, quadriceps weakness | 40–55% | Deflazacort ACE inhibitors 26 years |

| Patient 2 | 40 | 17 | Exons 45–49 | 60%, 380 kDa |

452 | HyperCKemia, pes cavus, difficulty rising from the floor, calf atrophy, weakness | 55% | Deflazacort 20 years |

| Patient 3 | 33 | 1 1/2 | Exons 48–51 | 90%, 370 kDa |

189 | Slight hyperCKemia, muscle cramps, quadriceps weakness | 65% | No |

| Patient 4 | 41 | 6 | Exons 31–44 | 35%, 320 kDa |

3086 | HyperCKemia, mild mitral valve insufficiency | 55% | No |

| Patient 5 | 17 | 6 | Exons 45–47 | 20%, 380 kDa |

1092 | HyperCKemia, calf hypertrophy | 64% | No |

| Patient 6 | 14 | 3 | Exons 45–51 | 50%, 370 kDa |

668 | HyperCKemia, mild winging scapulae | 65% | No |

| Patient 7 | 30 | 1 1/2 | Exons 48–49 | 50%, 380 kDa |

1305 | HyperCKemia, slight scoliosis, calf hypertrophy | 55% | No |

| Patient 8 | 45 | Childhood | Exons 47–49 | N.A. | 597–943 | HyperCKemia, slight scapular winging, calf hypertrophy | 55% | No |

2.1. Expression Levels of myo-miRNAs

2.2. Expression Levels of Inflammatory MiRNAs

2.3. Quantitative Expression of Myostatin/Follistatin

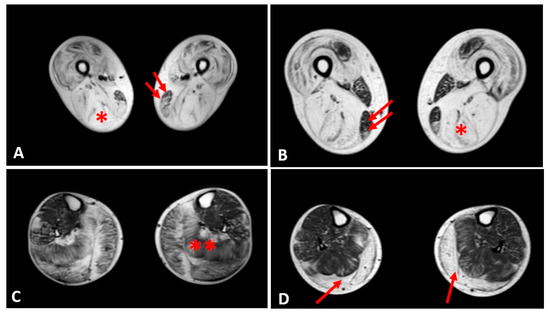

2.4. Muscle MRI Changes

Thigh muscles showed significant fatty infiltration of muscles in the anterior and posterior compartment in patient 1 and patient 2 who were treated with steroids. Both quadriceps and posterior hamstrings muscles were equally affected; only gracilis and sartorius muscles were spared in these two patients (Figure 4).

In the other patients, the thigh muscles were normal or slightly compromised, except for patients 7 and 8, in whom the fatty tissue infiltration in hamstring muscles reached Mercuri score 2a.

The posterior leg compartment was mostly affected in the two patients treated by steroids, showing severe fatty infiltration in gastrocnemius muscle. In the anterior leg, tibialis anterior was slightly involved; these 2 patients showed a Mercuri score 2a (Figure 4).

The other patients did not present a specific pattern of leg muscles involvement.

3. Conclusion

Concerning follistatin, the pivotal function of this protein is the inhibition of the myostatin pathway in order to regulate the muscle mass in muscular dystrophies. Several myostatin inhibitory drugs have been evaluated in neuromuscular diseases, but so far, the clinical results are limited [44]. In a gene therapy trial based on the use of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector with preliminary prednisone treatment, follistatin was injected in six BMD ambulatory patients, and there was in four patients increase in the distance walked in six-minute test (6MWT) and reduced endomysial fibrosis, muscle hypertrophy especially at high dose [45,46]. It is possible that such follistatin gene therapy combined with long-term deflazacort regime could be used in the future to treat the symptoms and maintain muscle strength in BMD patients. In future studies, sonography could be also utilized as alternative to muscle MRI, to evaluate quality of muscle mass since this technique is a cost-effective tool recently developed for evaluation of metabolic syndrome and adults dynapenia [47,48]. We propose that circulating miRNAs and myostatin could be used as a noninvasive prognostic biomarkers to monitor the progression and the treatment of the disease. We suggest as a clinical prospective and possible applicability of this study the combined use of circulating biomarkers with muscle MRI and sonography in order to improve diagnosis and disease management in both young dystrophinopathy and chronic adult myopathy patients.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diagnostics10090713