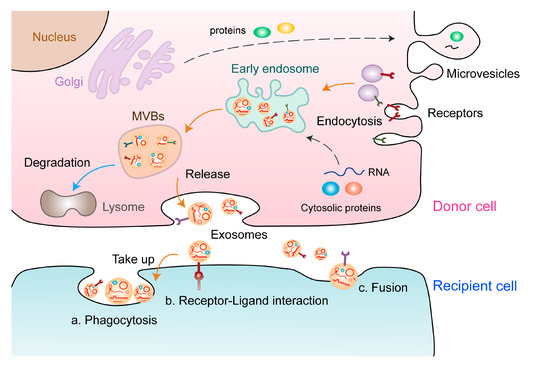

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) act as multifunctional regulators of intercellular communication and are involved in diverse tumor phenotypes, including tumor angiogenesis, which is a highly regulated multi-step process for the formation of new blood vessels that contribute to tumor proliferation. EVs induce malignant transformation of distinct cells by transferring DNAs, proteins, lipids, and RNAs, including noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs). However, the functional relevance of EV-derived ncRNAs in tumor angiogenesis remains to be elucidated. In this review, we summarized current research progress on the biological functions and underlying mechanisms of EV-derived ncRNAs in tumor angiogenesis in various cancers. In addition, we comprehensively discussed the potential applications of EV-derived ncRNAs as cancer biomarkers and novel therapeutic targets to tailor anti-angiogenic therapy.

- noncoding RNAs

- extracellular vesicles

- tumor angiogenesis

1. Characteristics of EVs and ncRNAs

2. EV-Derived ncRNAs: New Players in Tumor Angiogenesis

| EV-Derived ncRNAs | Expression | Source Cell | Function and Mechanism | Tumor Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-155 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis via the c-MYB/VEGF axis | Gastric cancer | [53] |

| Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis by inhibiting FOXO3a | Gastric cancer | [54] | |

| miR-130a | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Activates angiogenesis by inhibiting c-MYB | Gastric cancer | [55] |

| miR-135b | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis by inhibiting FOXO1 | Gastric cancer | [56] |

| Upregulated | Tumor cell | Regulates the HIF/FIH signalling pathway | Multiple myeloma | [57] | |

| miR-23a | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits PTEN and activates the AKT pathway | Gastric cancer | [58] |

| Upregulated | Tumor cell | Increases angiogenesis by inhibiting ZO-1 | Lung cancer | [59] | |

| miR-200b-3p | Downregulated | Tumor cell | Enhances endothelial ERG expression | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [60] |

| miR-25-3p | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits KLF2 and KLF4, thereby elevating VEGFR2 expression | Colorectal cancer | [61] |

| miR-1229 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits HIPK2, thereby activating the VEGF pathway | Colorectal cancer | [62] |

| miR-183-5p | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits FOXO1, thereby promoting expression of VEGFA, VEGFAR2, ANG2, PIGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 | Colorectal cancer | [63] |

| miR-142-3p | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits TGFβR1 | Lung adenocarcinoma | [64] |

| miR-103a | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits PTEN, thereby promoting the polarization of M2 macrophages | Lung cancer | [65] |

| miR-126 | Upregulated | MSCs | Upregulates CD34 and CXCR4, thereby promoting expression of VEGF | Lung cancer | [66] |

| miR-141-3p | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits SOCS5, thereby activating JAK/STAT3 and NF-κB signalling pathways | Ovarian cancer | [67] |

| miR-205 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Regulates the PTEN/AKT pathway | Ovarian cancer | [68] |

| miR-9 | Downregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits MDK, thereby regulating the PDK/AKT signalling pathway | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | [69] |

| Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis by targeting COL18A1, THBS2, PTCH1, and PHD3 | Glioma | [70] | |

| miR-23a | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis by inhibiting TSGA10 | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | [71] |

| miR-210 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Enhances tube formation by inhibiting EFNA3 | Leukemia | [72] |

| Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis by inhibiting SMAD4 and STAT6 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [73] | |

| miR-26a | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits PTEN, thereby activating the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway | Glioma | [74] |

| miR-27a | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits BTG2, thereby promoting VEGF, VEGFR, MMP-2, and MMP-9 expression | Pancreatic cancer | [75] |

| miR-155-5p /miR-221-5p |

Upregulated | M2 macrophages | Promotes angiogenesis by targeting E2F2 | Pancreatic cancer | [76] |

| miR-21-5p | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis by targeting TGFBI and COL4A1 | Papillary carcinoma | [77] |

| miR-100 | - - | MSCs | Regulates the mTOR/HIF-1α signalling axis | Breast cancer | [78] |

| miR-21 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits SPRY1, thereby promoting VEGF expression | Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma | [79] |

| Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits PTEN, thereby activating PDK1/AKT signalling | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [80] | |

| miR-181b-5p | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits PTEN and PHLPP2, thereby activating AKT signalling | Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma | [81] |

| miR-9 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits S1P, thereby promoting VEGF expression | Medulloblastoma and xenoglioblastoma | [82] |

| miR-10a-5p | Upregulated | CAFs | Inhibits TBX5, thereby activating Hedgehog signalling | Cervical squamous cell carcinoma | [83] |

| miR-135b | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Enhances angiogenesis by targeting FIH-1 | Multiple myeloma | [57] |

| miR-130b-3p | Upregulated | M2 macrophages | Regulates the miR-130b-3p/MLL3/GRHL2 signalling cascade | Gastric cancer | [84] |

| lncGAS5 | Downregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits angiogenesis by regulating the miR-29-3p/PTEN axis | Lung cancer | [85] |

| lnc-CCAT2 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes VEGFA and TGF-β expression | Glioma | [86] |

| lnc-POU3F3 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes bFGF, bFGFR, and VEGFA expression | Glioma | [87] |

| lncRNA RAMP2-AS1 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis through the miR-2355-5p/VEGFR2 axis | Chondrosarcoma | [88] |

| OIP5-AS1 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Regulates angiogenesis and autophagy through miR-153/ATG5 axis | Osteosarcoma | [89] |

| FAM225A | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis through the miR-206/NETO2/FOXP1 axis | Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma | [51] |

| UCA1 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis through the miR-96-5p/AMOTL2 axis | Pancreatic cancer | [90] |

| SNHG11 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis through the miR-324-3p/VEGFA axis | Pancreatic cancer | [91] |

| SNHG1 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis by regulating the miR-216b-5p/JAK2 axis | Breast cancer | [92] |

| AC073352.1 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Binds and stabilizes the YBX1 protein | Breast cancer | [93] |

| MALAT1 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Facilitates angiogenesis and predicts poor prognosis | Ovarian cancer | [94] |

| TUG1 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis by inhibiting caspase-3 activity | Cervical cancer | [95] |

| LINC00161 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis and metastasis by regulating the miR-590-3p/ROCK axis | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [96] |

| H19 | Upregulated | Cancer stem cell | Promotes VEGF production and release in ECs | Liver cancer | [97] |

| circSHKBP1 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Enhances VEGF mRNA stability by the miR-582-3p/HUR axis | Gastric cancer | [52] |

| circRNA-100,338 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Facilitates HCC metastasis by enhancing invasiveness and angiogenesis | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [98] |

| circCMTM3 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes angiogenesis and HCC tumor growth by the miR-3619-5p/SOX9 axis | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [99] |

| circ_0007334 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Accelerates CRC tumor growth and angiogenesis by the miR-577/KLF12 axis | Colorectal cancer | [100] |

| CircFNDC3B | Downregulated | Tumor cell | Inhibits angiogenesis and CRC progression by the miR-937-5p/TIMP3 axis | Colorectal cancer | [101] |

| circGLIS3 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Induces endothelial cell angiogenesis by promoting Ezrin T567 phosphorylation | Glioma | [102] |

| piRNA-823 | Upregulated | Tumor cell | Promotes VEGF and IL-6 expression | Multiple myeloma | [103] |

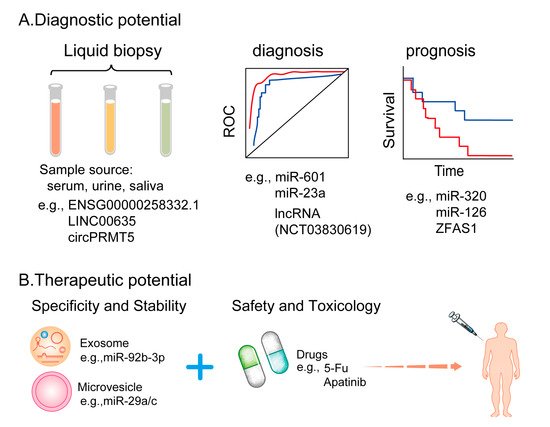

3. Potential Clinical Applications of EV-Derived ncRNAs in Cancers

3.1. EV-Derived ncRNAs as Promising Tumor Biomarkers

3.2 EV-Derived ncRNAs as Potential Anti-Angiogenic Therapeutic Targets

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11060947