Vector-borne diseases are among the most rapidly spreading infectious diseases and are widespread all around the world. In China, many types of vector-borne diseases have been prevalent in different regions, which is a serious public health problem with significant association with meteorological factors and weather events. Under the background of current severe climate change, the outbreaks and transmission of vector-borne diseases have been proven to be impacted greatly due to rapidly changing weather conditions.

1. Introduction

Except for COVID-19, climate change may be the most important global public health issue of our time [

1] since it threatens all aspects of human health, including the risks of infectious diseases [

2]. Vector-borne disease is one of the infectious diseases most sensitive to climate. It has put 80% of the population at infection risk [

3] and causes more than 700,000 deaths every year all around the world [

4]. Unfortunately, climatic conditions, especially rising temperature, have also been contributing to outbreaks of vector-borne diseases in recent years [

5]. Previous studies have predicted that the spreading areas of vector-borne diseases will expand in many countries due to a rapidly changing climate [

6,

7]. Climate change has been proven to be one of the key drivers of changing the life activities, living environments, migration, and geographical distribution of vectors [

8,

9], which will ultimately increase the risk of vector-borne diseases [

10].

China is one of the most vulnerable countries with respect to climate change [

11]. Many studies have found the significant positive relationship between weather conditions and vector-borne diseases in China, including the effects of meteorological factors, such as temperature, precipitation, humidity, wind speed [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], and extreme weather events (e.g., extremely high temperatures, extremely high rainfall, and tropical cyclones) [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The 2020 China Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change showed that China’s climate suitability for mosquito-borne dengue fever has increased by 37% in the past half century [

25]. If nothing is done to address climate change, the malaria incidence in northern China will rise from 69% to 182% by 2050 [

26].

2. Climate Change and Vector-Borne Diseases in China

2.1. The Relationship between Meteorological Factors and Vector-Borne Diseases

Most published studies used ecological design for risk assessment, in which the most frequently used mathematical models were the Ecological Niche Model (ENM), Distributed Lag Non-linear Model (DLNM), Generalized Estimated Equation (GEE), Generalized Linear Model (GAM), Logistic Regression and Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average Model (ARIMA), etc. The relationship between climate factors and vector-borne diseases was non-linear; a J-shape or reverse U-shape was always found between them, which means, respectively, that the risks increased continuously or increased and then decreased with the rise of certain meteorological factors. Temperature, precipitation, and humidity were the main parameters contributing to the transmission of vector-borne diseases [

13,

50,

51,

52]. Generally, temperature plays an important role in the number of reported insect-borne and rodent-borne diseases cases [

42,

53,

54,

55,

56]. However, typhus group rickettsiosis was negatively related to average temperature, average ground temperature, and extreme minimum temperature [

13]. The same negative correlation was also found between temperature and schistosomiasis [

47]. Precipitation can promote the transmission of most insect-borne diseases [

57,

58] and interacts with temperature [

16]. It is expectable that moderate precipitation (10–120 mm) and temperatures of 10–25 °C were the most favorable condition for HFRS incidence [

59]. In addition, rising humidity is facilitates insect-borne disease transmission, such as dengue and plague [

60,

61]. Atmospheric pressure and wind speed were inversely related to vector-borne diseases but sunshine was positively related [

52,

62,

63].

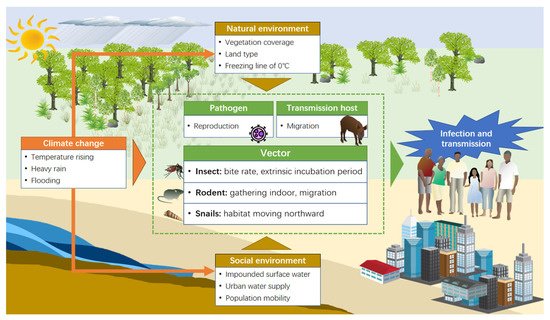

2.2. Potential Pathway of Meteorological Factors on Vector-Borne Diseases

Figure 3 shows the main effect path of the climate change on vector-borne diseases. Climate change can contribute to a lot of environmental problems, such as changing vegetation cover and land type, accelerating the melting of snow, and exacerbating the urban heat island effect, impacting urban water supply systems and population mobility. These changes can lead to the disruption of ecosystems’ balance and loss of wildlife habitats, which may affect the reproduction, survival, spread, and distribution of pathogens, vectors, or intermediate hosts, ultimately increasing the risk of vector-borne diseases [

71].

Figure 3. The main pathway of climate change impact on the risk of vector-borne diseases.

Rising temperatures can shorten the incubation and reproduction rates of dengue viruses and the life cycle of mosquitoes, which can contribute to the increase in the number and spread rate of vectors [

66,

72,

73]. Moreover, high temperatures can increase vectors’ survival rate [

74], but when the temperature exceeds a certain threshold, it has an adverse effect on the reproduction and bite rates of insects [

75]. When the temperature continues to be above 37 °C for several days, the mosquito breeding grounds are reduced by the evaporation of water, which in turn leads to a decrease in mosquito density and affects the prevalence of malaria [

76]. Snails are the vectors of schistosomiasis and cannot survive in areas where temperatures are below 0 °C in January. Studies have proven that the habitat suitable for snails in Poyang Lake has moved northward due to rising temperatures [

48,

77,

78]. In addition, rising soil surface temperatures can significantly affect the transmission of leishmaniasis by impacting the growth and development of its vector, sandflies, which carry out life activities in the first three life stages in soil close to the surface [

79].

Precipitation can provide more habitats for mosquitoes, contributing to their survival and reproduction [

80,

81]. However, extreme precipitation can destroy vector habitats, disrupt the growth of insects, and wash eggs out of breeding grounds, further decreasing vector density and disease transmission [

81,

82,

83]. Some scholars also believe that although heavy precipitation takes away vector organisms, the rest of the rain will become a potential breeding ground for adult mosquitoes [

84]. In addition, heavy rainfall in eastern China also destroys rodent habitats, reducing rodent–rodent contact, human–rodent contact, and the spread of the virus [

18]. However, in southern China, the migration of infected people and rodents may promote the spread of plague between regions, although flooding can kill the vectors [

61].

2.3. The Regional Differentiation of the Relationship between Meteorological Factors and Vector-Borne Diseases

Both the relationship and the mechanism mentioned above have shown large regional differences. The correlation between the main meteorological factors (temperature, precipitation and humidity) and vector-borne diseases in different provincial/municipal/county administrative regions are shown in Table 2, in which “+” represents a positive correlation, “−” represents a negative correlation, “J” represents a J-shaped correlation, and “reverse U” represents a reverse U-shaped correlation. Generally, in southern China, temperature may contribute to the transmission of insect-borne diseases while adversely affecting it in the northern region. In contrast, the number of rodent-borne diseases cases may be decreased by temperature in southern China but be increased in the northern region. Meanwhile, a positive association between precipitation and insect-borne diseases can be found in the southern China, while the same relationship between precipitation and rodent-borne diseases is mainly distributed in the northern region.

The pathway of climate change impacting vector-borne diseases can also vary among regions. Small increases in temperature can greatly affect the spread of malaria in areas with lower average temperatures since the prevalence of malaria in hotter regions is much higher than in colder regions [

85]. In addition, rainwater does not gather readily in the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau because of the typical mountainous characteristics of it, and currents can destroy mosquito breeding habitats and reduce mosquito population density, which may not lead to the incidence of JE increasing with increases in rainfall in this area [

86]. Heavy precipitation can also destroy rodents’ habitats and reduce its populations. However, due to low winter temperatures in northern China, heavy precipitation may cause rodents to gather indoors, increasing the likelihood of human–rodent contact [

16,

70].

Table 2. The relationships between meteorological factors and vector-borne diseases according to the classification of different administrative regions in China.

| Disease |

Area |

Time Period |

Meteorological Factors |

| Temperature |

Precipitation |

Humidity |

| Malaria |

Shandong |

|

|

|

|

| Jinan City |

1959–1979 |

Max T (+) ** |

P (+) |

H (+) * |

| |

|

Min T (+) ** |

|

|

| Henan |

|

|

|

|

| Yongcheng County |

2006–2010 |

Monthly avg max T (+) *** |

- |

Monthly avg H (+) ** |

| Anhui |

1990–2009 |

Monthly avg T(+) * |

Monthly avg P (+) ** |

Monthly avg RH (+) * |

| Shuchen County |

1980–1991 |

Monthly avg max T (+) ***

Monthly avg min T (+) *** |

Monthly P (+) *** |

Monthly avg RH (+) *** |

| Hefei city |

1999–2009 |

Monthly avg T (+)

Monthly avg max T (+) ***

Monthly avg min T (+) *** |

P (+) * |

H (+) *** |

| Hefei City |

1990–2011 |

Monthly min T (+) *** |

P |

RH (+) *** |

| Yunnan |

|

|

|

|

| Mengla County |

1971–1999 |

Monthly max T (+) *

Monthly min T (+) * |

Monthly P (−) |

Monthly RH (−) |

| 125 counties |

2012 |

Yearly avg T (+) ** |

Yearly P (+) ** |

|

| Guangdong |

2005–2013 |

High T (+) |

P (J) |

- |

| Guangzhou city |

2006–2012 |

Daily avg T (+) * |

- |

Daily RH (+) * |

| Hainan |

1995–2008 |

Monthly avg T (+) *

Monthly avg max T (+) *

Monthly min T (+) * |

Monthly total P (+) * |

- |

| Dengue |

Guangdong |

|

|

|

|

| Guangzhou City |

2006–2015 |

Extremely high T (+) * |

Extremely high P (+) * |

Extremely high H (+) * |

| Guangzhou City |

2005–2015 |

Monthly avg max T (+) ** |

Monthly total P (+) ** |

- |

| Guangzhou City |

2007–2012 |

Monthly avg T (+) ** |

- |

Monthly avg RH (+) ** |

| Guangzhou City |

2001–2006 |

Min T (+) *** |

Monthly total P (+) |

Min H (+) |

| Guangzhou City |

2000–2012 |

Monthly avg min T (+) * |

Monthly total P (+) * |

Monthly avg RH (+) * |

| Guangzhou City |

2005–2011 |

Daily avg T (+) *

Daily min T (+) *

Daily max T (−) * |

Daily P (+) |

Daily H (+) |

| Zhongshan City |

2001–2013 |

Monthly max T (+) *

Monthly max DTR (+) * |

- |

Monthly avg RH (+) *

Monthly max RH (+) * |

| Fujian |

1978–2017 |

Monthly avg T (+) * |

Monthly total P (+) * |

- |

| Guangxi |

1978–2017 |

Monthly avg T (+) * |

Monthly total P (+) * |

- |

| Yuanan |

1978–2017 |

Monthly avg T (+) * |

Monthly total P (+) * |

- |

| Japanese encephalitis |

Shandong |

|

|

|

|

| Jinan City |

1959–1979 |

Monthly avg max T (+) ***

Monthly avg min T (+) *** |

Monthly total P (+) * |

Monthly avg RH (+) *** |

| Linyi City |

1956–2004 |

Monthly min T (+) ** |

- |

Monthly avg RH (+) * |

| Shannxi |

2006–2014 |

Monthly min T (−) |

Monthly P (+) |

- |

| Anhui |

|

|

|

|

| Jieshou County |

1980–1996 |

Monthly avg max T (+) *

Monthly avg min T (+) * |

Monthly total P (+) ** |

- |

| Hunan |

|

|

|

|

| Changsha city |

2004–2009 |

Monthly avg max T (+) *

Monthly avg min T (+) * |

Monthly total P (+) * |

Monthly avg AH (+) * |

| Sichuan |

|

|

|

|

| Nanchong City |

2007–2012 |

Daily avg T (+) * |

- |

Daily avg RH (+) * |

| Chongqin |

|

|

|

|

| 12 counties along the Yangtze River |

1997–2008 |

Monthly avg T (+) *** |

Monthly total P (−) *** |

- |

| Scrub typhus |

Shandong |

2006–2013 |

Monthly avg T (reversed U) *** |

Monthly total P (−) *** |

Monthly avg RH (−) *** |

| Laiwu City |

2006–2012 |

Monthly avg T (+) ** |

Monthly avg P (+) ** |

Monthly avg RH (+) ** |

| Anhui |

2006–2013 |

Monthly avg T (reversed U) *** |

Monthly total P (−) *** |

Monthly avg RH (+) *** |

| Jiangsu |

2006–2013 |

Monthly avg T (reversed U) *** |

Monthly total P (−) *** |

Monthly avg RH (+) *** |

| Yancheng City |

2005–2014 |

Monthly avg min T (+) *** |

Monthly total P (+) *** |

Monthly avg RH (−) *** |

| Guangdong |

|

|

|

|

| Guangzhou City |

2006–2012 |

Daily avg T (+) ** |

Daily P (+) ** |

Daily avg RH (−) * |

| Typhus group rickettsiosis |

Yunan |

|

|

|

|

| Xishuangbanna |

2005–2017 |

Weekly avg T (J) * |

Weekly avg P (reversed U) * |

- |

| SFTS |

Jiangsu |

2010–2016 |

Max T in warmest month (+) * |

P in warmest month (+) * |

- |

| Leishmaniasis |

Xinjiang |

|

|

|

|

| Jiashi County |

2005–2015 |

Monthly avg T (+) ** |

Monthly total P |

Monthly avg RH (−) ** |

| Plague |

Gansu |

|

|

|

|

| Sunan County, Subei County |

1973–2016 |

Monthly avg T (+) * |

Monthly avg P (+) * |

Monthly avg RH (−) * |

| |

Yunnan |

1982–2013 |

Extreme max T (−) ** |

- |

Avg RH (+) ** |

| HFRS |

Guizhou |

1982–2013 |

Extreme max T (−) ** |

- |

Avg RH (+) ** |

| Guangxi |

1982–2013 |

Extreme max T (−) ** |

- |

Avg RH (+) ** |

| Liaoning |

2005–2014 |

Weekly max T (+) * |

Weekly P (+) * |

Weekly avg RH (+) * |

| Shenyang City |

2004–2009 |

Monthly avg T (−) *

Monthly avg max T (−) *

Monthly avg min T (−) * |

Monthly total P (−) * |

Monthly avg RH (−) * |

| |

Heilongjiang |

2005–2014 |

Weekly max T (+) * |

Weekly P (+) * |

Weekly avg RH (+) * |

| |

Anhui |

2005–2014 |

Weekly max T (+) * |

Weekly P (+) * |

Weekly avg RH (+) * |

| Schistosomiasis |

Hubei |

1976–1989 |

Avg T in July (−) * |

Avg P in July (−) * |

- |

| |

Anhui |

1997–2010 |

Monthly avg T (−) * |

Monthly total P (−) * |

|

| |

Jiangxi |

2008 |

- |

Monthly min P (−) **

Monthly max P (−) ** |

|

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biology11030370