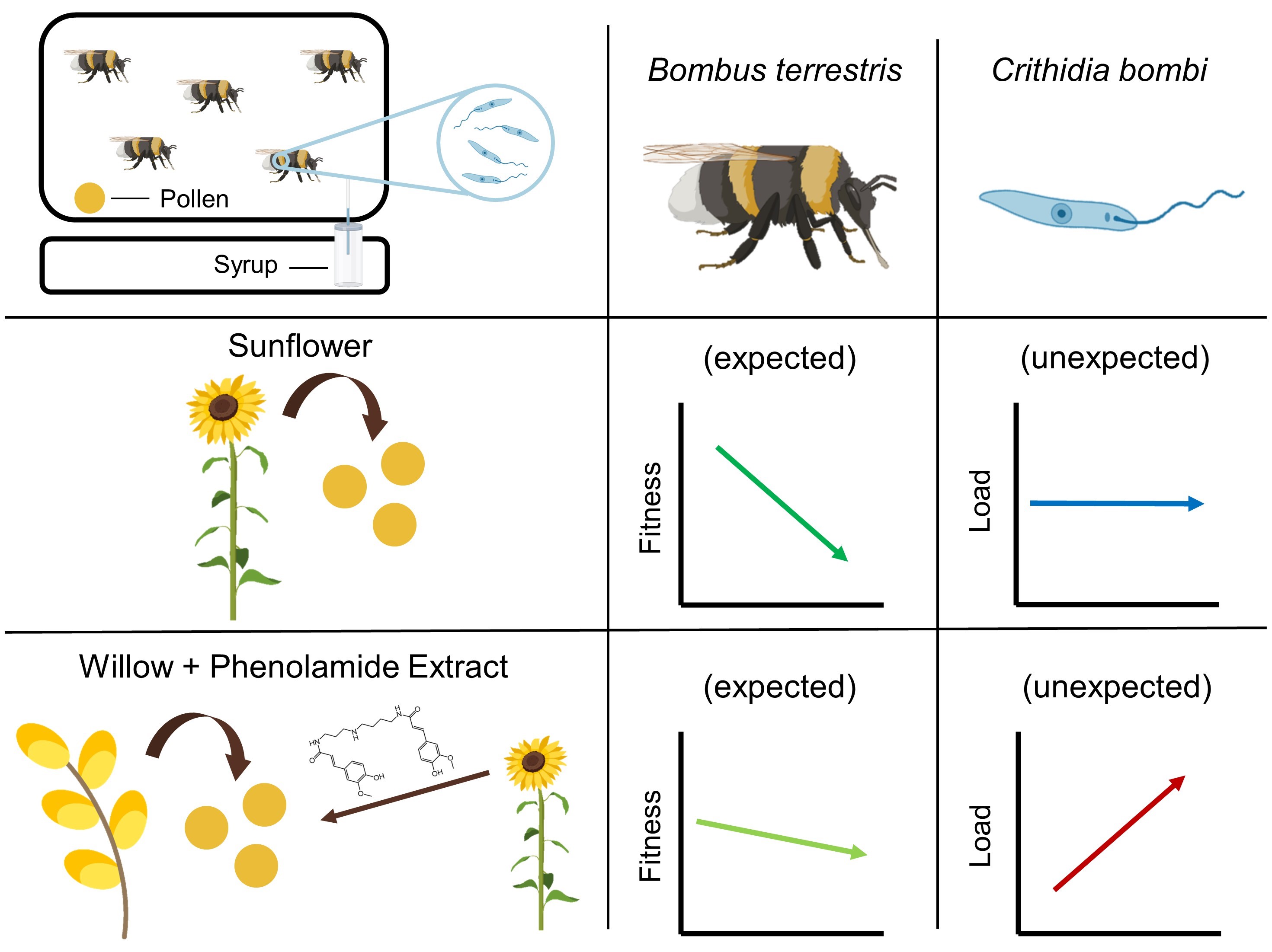

Bees may forage on specific floral resources to face parasite infection. Such natural resources are comparable to ‘natural pharmacies’ and may be favoured in bee conservation strategies. Consumption of sunflower pollen, despite being detrimental for larval development, has been recently shown to reduce the load of a widespread bumble bee gut parasite in the common eastern bumble bee. Although the underlying mechanisms remain unknown, it has been suggested that sunflower phenolamides—a family of molecules found in most flowering plants—may be responsible for such a reduction in parasite load.

- Crithidia bombi

- Bombus terrestris

- Helianthus annuus

- Specialised metabolites

- Microcolony performance

- Phenotypic variation

- Immunocompetence

1. Introduction

2. Phenolamide Allocation in Sunflower

3. Effects of Sunflower Pollen and Phenolamides on Bumble Bees

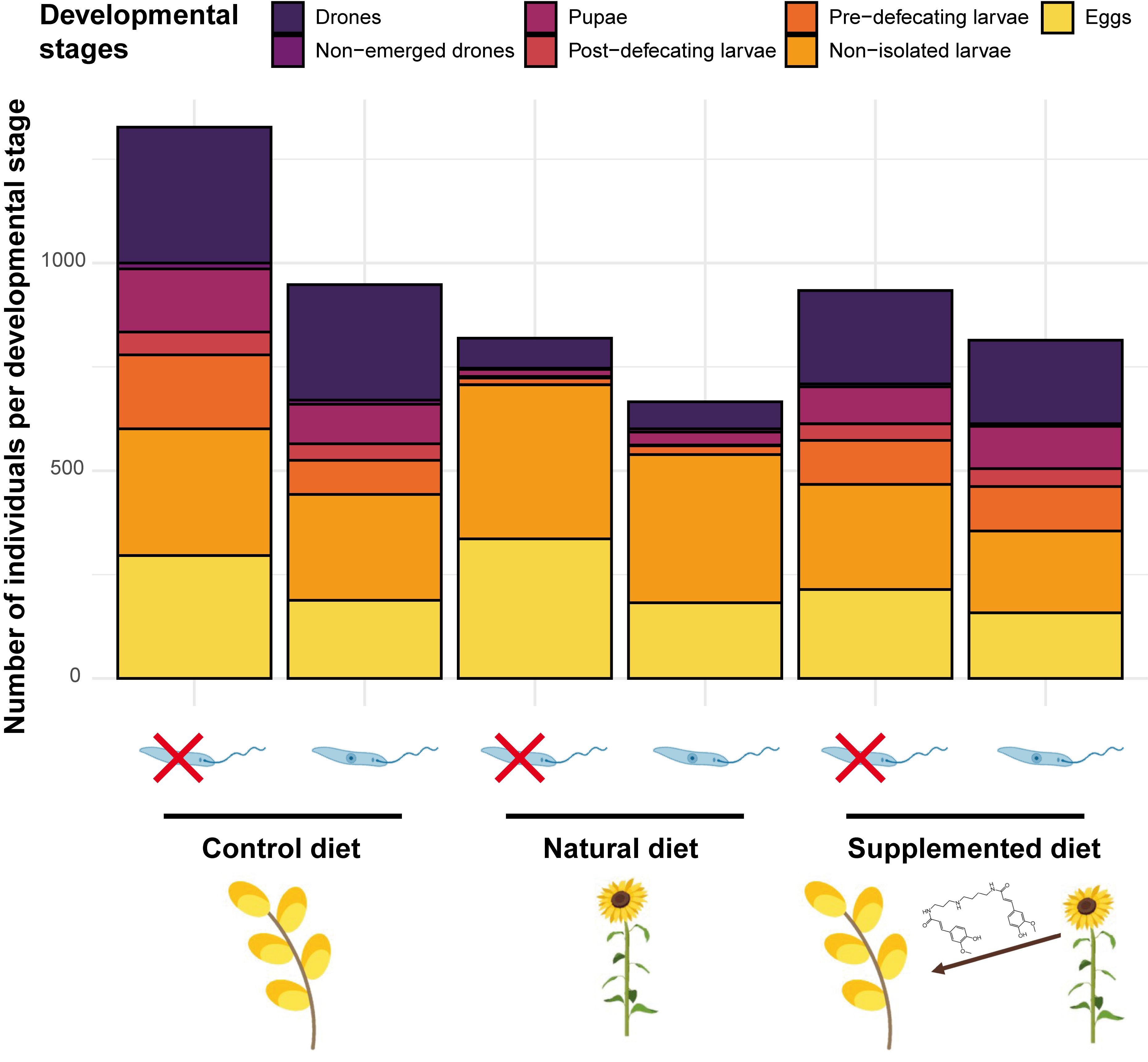

Sunflower pollen is not suitable for bumble bee development mainly due to nutritional deficiencies [40] but also to the occurrence of potentially toxic specialised metabolites (e.g., alkaloids [3]) and to the peculiar morphology of exine, which is typical of Asteraceae [41][42]. As no compensatory feeding behaviour (i.e., increased pollen collection) has been highlighted, it suggests that unsuitability may be due to pollen toxicity or low digestibility rather than to nutritional deficiencies (e.g., [5]). Actually, microcolonies fed a supplemented diet also produced a reduced number of males and a restricted offspring mass, suggesting that phenolamides may partly explain sunflower unsuitability (Figure 1). They also displayed a higher pollen dilution, which is known as a behaviour allowing for mitigation of unfavourable pollen properties (e.g., [43]). However, neither natural nor supplemented diets induced mortality among the B. terrestris workers. Such unsuitable but sublethal effects of sunflower phenolamides might arise from their antifungal and antibacterial properties [44][45] that may disrupt the bumble bee microbiota (e.g., by boosting/depleting some phylotypes [46]). Moreover, phenolamides are known to upregulate some genes in bees that are homologous to those that stimulate rapid excretion in other insects [47], suggesting that phenolamides might negatively alter bumble bee physiology.

Figure 1. Microcolony development across treatments.

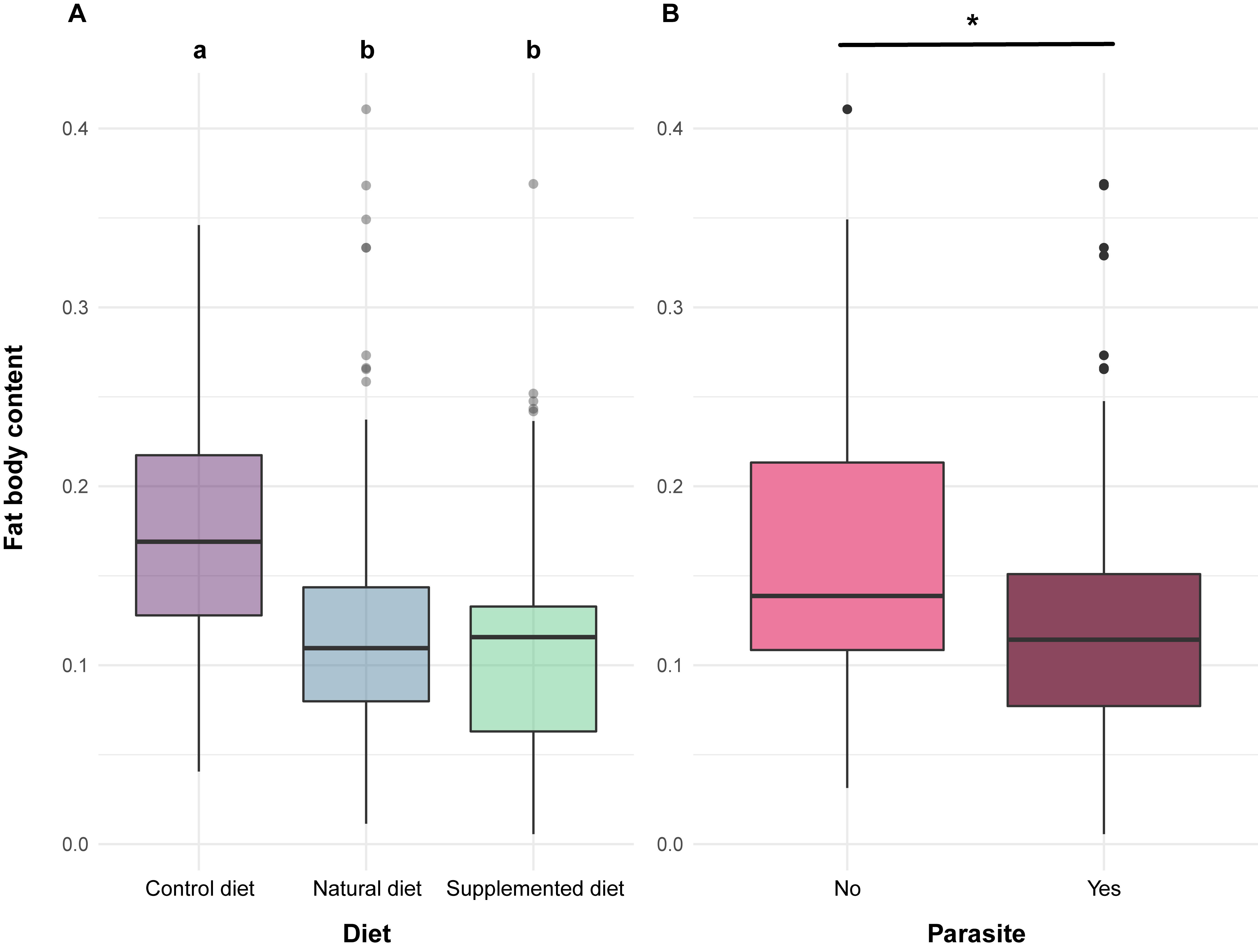

Alongside these effects reported in the literature, the bioassays highlighted that phenolamides also induced a reduction in fat body content, which is a major component of the immune system [48]. Indeed, individuals fed a supplemented or natural diet displayed lower fat body content compared to those fed a control diet (Figure 2). As natural and supplemented diets have different nutritive composition (i.e., one based on sunflower pollen, the other based on willow pollen as for the control diet), this effect cannot arise from differences in pollen nutrients or digestibility. The only valid explanation would be the contribution of the fat body in the detoxification of allelochemical compounds [49]. Actually, the occurrence of phenolamides in both natural and supplemented diets could have activated detoxification pathways, leading to metabolic costs associated with a reduction in lipid reserves (i.e., fat body).

Regarding phenotypic variation, the occurrence of phenolamides in the pollen diet also impacted the shape of the forewing and increased shape fluctuating asymmetry (FA) in newly emerged males (i.e., significant differences among males reared on different diets). Such effects of specialised metabolites on male wing shape have already been highlighted in similar bioassays using sinigrin and amygdalin-supplemented diets [50] and can be indicative of changes in environmental conditions or presence of stressors [51]. By contrast, levels of FA are often lower under controlled conditions [50], and the increase in FA in stressful conditions is indicative of a lesser developmental stability, meaning that males are challenged during their development, which leads to deviations from perfect symmetry between each side [52]. The mechanism explaining such modifications under various stressors remains unclear, but it has been proposed that a shift in energy allocation (e.g., activation of detoxification pathways) can occur and then weaken the homeostasis, ultimately impacting the phenotype [53].

4. Infection Costs of a Gut Parasite on Bumble Bees

While diet effects on microcolonies were strongly pronounced, only mild effects of the gut parasite Crithidia bombi were observed since infected microcolonies did not display neither higher mortality nor higher stress responses than uninfected ones. Actually, C. bombi is known to be a highly prevalent but not too virulent gut parasite [54]. While a compensatory feeding behaviour (i.e., increased pollen collection) and reduced survival have been highlighted in infected Bombus impatiens workers [55], these effects were not observed herein for B. terrestris, suggesting that differences in susceptibility occur among bumble bee species.

As expected, due to the immune challenge, parasite infection resulted in a significant decrease in fat body content (Fig 2). However, such an effect has never been highlighted in previous laboratory studies investigating the impact of the parasite on bumble bees’ fat bodies, probably because of the experimental design that implied isolating each individual for a short period [21][56]. Individuals were maintained within microcolonies and likely constantly reinfected themselves via nestmate faeces and brood with a continuous exposure for 35 days [57], which could have resulted in a greater immune challenge than in previous studies.

Figure 2. Fat body content in bumble bee individuals.

Regarding the phenotypic variation, the parasite did not impact any of the measured parameters (i.e., centroid size, wing shape, size FA, and shape FA). This result contrasts with a previous study showing that Apicystis bombi (Apicomplexa: Neogregarinorida) impacted wing size and shape as well as size FA [50]. This discrepancy could be explained by the difference in parasites’ host life stages. Indeed, A. bombi infects all brood stages as well as adults, challenging the bumble bees during their development, whereas C. bombi only infects adults without any developmental challenge [57].

5. Effects of Sunflower Pollen and Phenolamides on a Gut Parasite

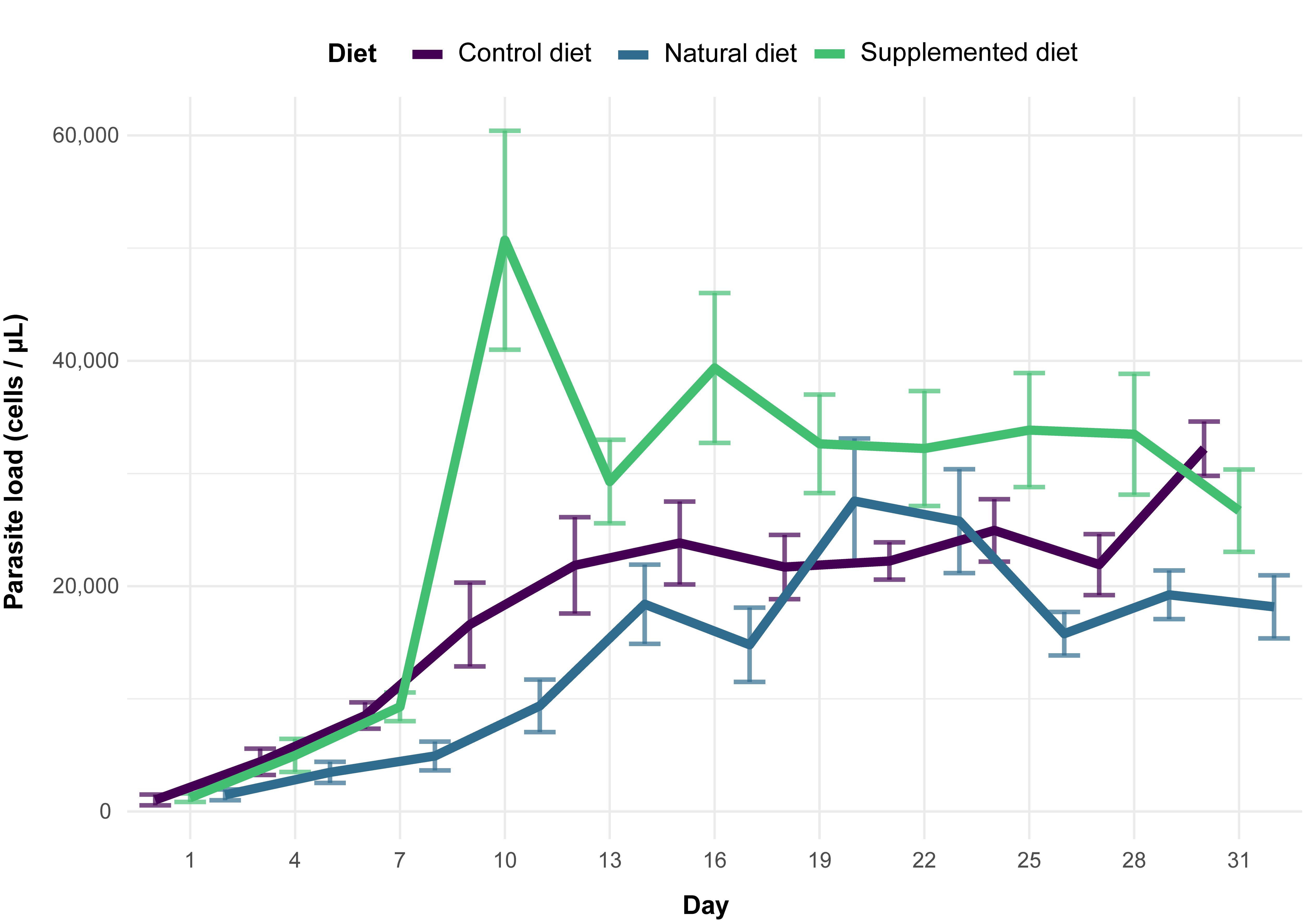

It was shown that sunflower pollen did not reduce C. bombi load in the bumble bee B. terrestris (Figure 3). This observation is quite surprising and unexpected given the plethora of previous studies that systematically found a medicinal effect of sunflower pollen in infected bumble bees in different experimental designs (i.e., different sunflower cultivars, different parasite strains, workers housed individually or in microcolonies) [27][28][29][30][31][32]. One explanation would be the difference in the host bumble bee species as this entry used B. (Bombus) terrestris whereas previous studies used B. (Pyrobombus) impatiens, which modifies the host genotype x parasite genotype x environment interacting factor in the Bombus–Crithidia system [22]. Such a discrepancy has recently been demonstrated by Fowler et al. [58] who showed that sunflower pollen reduced Crithidia load in B. impatiens, B. bimaculatus and B. vagans (subgenus Pyrobombus) but not in B. griseocollis (subgenus Cullumanobombus). Another difference in the experimental design is the delay between parasite inoculation and consumption of sunflower pollen, which seems to be a crucial parameter when assessing the medicinal effect of pollen diet. Indeed, previous studies indicated that infected bumble bees fed sunflower pollen 3.5 days after inoculation did not display any reduced parasite load compared to control, whereas infected bumble bees fed sunflower pollen right after inoculation displayed a reduced parasite load after seven days [29]. Discrepancies may also arise from difference in pollen used as the control diet, namely willow and buckwheat or wildflower mix in previous ones [27][28][29][30][31][32].

While no effect of sunflower pollen has been highlighted for parasite infection, phenolamides benefited the parasite as infected workers fed a supplemented diet displayed an increased parasite load (Figure 3). Such a parasite-facilitating effect of phenolamides has been already observed in a previous study, though it was less pronounced than herein, probably because of some differences between the experimental designs [32]. This effect could arise from different biological activities of phenolamides: (i) their antifungal and antibacterial properties [44][45] that may disrupt the gut microbiota and then weaken a crucial non-immunological defence [59]; (ii) their antioxidant and radical scavenging activities that may lead to a decrease in reactive oxygen species and an immunosuppressed state [60]; and (iii) their potential toxic activities that could result in activation of defence pathways (i.e., detoxification system), altering bee physiology, consuming their energy reserves and then weakening the whole organism that would not be disposed to face an immune challenge (e.g., [61]). While these results cannot unravel the mechanisms favouring parasite development in microcolonies fed a supplemented diet, it can however be proposed that phenolamides are not responsible for medicinal effects of sunflower as recently suggested by [33], that put forward a reduction in parasite load through more rapid excretion after sunflower pollen consumption.

Figure 3. Parasite load among diet treatments for 31 days (mean ± SE).

6. Focus for Future Research

Since all pollen diets display specialised metabolites with differing biological activities and potential physical properties, no one can clearly rule out potential effects of their control pollen diet on parasite load (i.e., favouring or impeding effects). One solution would be to use an artificial diet free of specialised metabolites and physical barriers, and suitable for microcolony development, or to clearly establish the absence of medicinal effects of the natural control pollen diet prior to bioassays (e.g., examining parasite growth through in vitro assays), which has never been thoroughly done. Besides this issue, the definition of ‘medicinal effects’ itself may be confusing. Importantly, a medicinal effect may occur either by benefiting the host or by hampering parasite growth. While some have claimed that a diet must compulsorily be detrimental to the parasite to be considered as medicinal [62], others have argued that it is not mandatory and proposed that medicinal diets could either increase host resistance or tolerance to infection [63]. Furthermore, detrimental effects on unicellular parasites cannot be only assessed based on cells count but should also be considered through molecular impacts on parasite cells such as impairment of protein synthesis, intercalation in DNA, disruption of cell wall, induction of apoptosis, or any other mechanism impeding parasite fitness such as flagellum loss (e.g., [23]). Experiments seeking the most suitable control diet when addressing medicinal effects of pollen on infected bees as well as experiments testing the molecular effects of pollen-specialised metabolites on parasite cells promise to bring new insights into the mechanisms underlying medicinal effects of pollen. Untangling such mechanisms would shed light on the way bees could use floral resources to overcome parasite challenge.

7. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biology11040545

References

- Anthony D Vaudo; John F Tooker; Christina M Grozinger; Harland M Patch; Bee nutrition and floral resource restoration. Current Opinion in Insect Science 2015, 10, 133-141, 10.1016/j.cois.2015.05.008.

- T. H. Roulston; J. H. Cane; Pollen nutritional content and digestibility for animals. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2000, 222, 187-209, 10.1007/bf00984102.

- Evan C. Palmer-Young; Iain W. Farrell; Lynn S. Adler; Nelson J. Milano; Paul A. Egan; Robert R. Junker; Rebecca E. Irwin; Philip C. Stevenson; Chemistry of floral rewards: intra- and interspecific variability of nectar and pollen secondary metabolites across taxa. Ecological Monographs 2018, 89, e01335, 10.1002/ecm.1335.

- Ch. Westerkamp; Pollen in Bee-Flower Relations Some Considerations on Melittophily*. Botanica Acta 1996, 109, 325-332, 10.1111/j.1438-8677.1996.tb00580.x.

- Kristen K. Brochu; Maria T. Van Dyke; Nelson J. Milano; Jessica D. Petersen; Scott H. McArt; Brian A. Nault; André Kessler; Bryan N. Danforth; Pollen defenses negatively impact foraging and fitness in a generalist bee (Bombus impatiens: Apidae). Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1-12, 10.1038/s41598-020-58274-2.

- Andreas Detzel; Michael Wink; Attraction, deterrence or intoxication of bees (Apis mellifera) by plant allelochemicals. Chemoecology 1993, 4, 8-18, 10.1007/bf01245891.

- Sarah E. J. Arnold; M. Eduardo Peralta Idrovo; Luis J. Lomas Arias; Steven Belmain; Philip Stevenson; Herbivore Defence Compounds Occur in Pollen and Reduce Bumblebee Colony Fitness. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2014, 40, 878-881, 10.1007/s10886-014-0467-4.

- Viki Hurst; Philip Stevenson; Geraldine A. Wright; Toxins induce ‘malaise’ behaviour in the honeybee (Apis mellifera). Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology 2014, 200, 881-890, 10.1007/s00359-014-0932-0.

- Michael Simone-Finstrom; David Baracchi; Mark J. F. Brown; Lars Chittka; Referee report. For: Behavioural evidence for self-medication in bumblebees? [version 2; referees: 3 approved]. F1000Research 1970, 4, 73, 10.5256/f1000research.7009.r8767.

- Sébastien Rivest; Jessica R. K. Forrest; Defence compounds in pollen: why do they occur and how do they affect the ecology and evolution of bees?. New Phytologist 2019, 225, 1053-1064, 10.1111/nph.16230.

- Philip C. Stevenson; For antagonists and mutualists: the paradox of insect toxic secondary metabolites in nectar and pollen. Phytochemistry Reviews 2019, 19, 603-614, 10.1007/s11101-019-09642-y.

- A. D. Vaudo; D. Stabler; H. M. Patch; J. F. Tooker; C. M. Grozinger; G. A. Wright; Bumble bees regulate their intake of the essential protein and lipid pollen macronutrients. Journal of Experimental Biology 2016, 219, jeb.140772-3970, 10.1242/jeb.140772.

- Maryse Vanderplanck; Baptiste Martinet; Luísa Gigante Carvalheiro; Pierre Rasmont; Alexandre Barraud; Coraline Renaudeau; Denis Michez; Ensuring access to high-quality resources reduces the impacts of heat stress on bees. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1-10, 10.1038/s41598-019-49025-z.

- Alexandre Barraud; Maryse Vanderplanck; Sugahendni Nadarajah; Denis Michez; The impact of pollen quality on the sensitivity of bumblebees to pesticides. Acta Oecologica 2020, 105, 103552, 10.1016/j.actao.2020.103552.

- Laura L. Figueroa; Cali Grincavitch; Scott H. McArt; Crithidia bombi can infect two solitary bee species while host survivorship depends on diet. Parasitology 2020, 148, 435-442, 10.1017/s0031182020002218.

- Arran J. Folly; Marta Barton‐Navarro; Mark J. F. Brown; Exposure to nectar‐realistic sugar concentrations negatively impacts the ability of the trypanosome parasite ( Crithidia bombi ) to infect its bumblebee host. Ecological Entomology 2020, 45, 1495-1498, 10.1111/een.12901.

- Roderick P Macfarlane; Jerzy J Lipa; Helen J Liu; Bumble Bee Pathogens and Internal Enemies. Bee World 1995, 76, 130-148, 10.1080/0005772x.1995.11099259.

- Ivan Meeus; Mark J. F. Brown; Dirk C. DE Graaf; Guy Smagghe; Effects of Invasive Parasites on Bumble Bee Declines. Conservation Biology 2011, 25, 662-671, 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01707.x.

- Robert J Gegear; Michael C Otterstatter; James D Thomson; Bumble-bee foragers infected by a gut parasite have an impaired ability to utilize floral information. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2006, 273, 1073-1078, 10.1098/rspb.2005.3423.

- Peter Graystock; Ivan Meeus; Guy Smagghe; Dave Goulson; William O. H. Hughes; The effects of single and mixed infections ofApicystis bombiand deformed wing virus inBombus terrestris. Parasitology 2015, 143, 358-365, 10.1017/s0031182015001614.

- M. J. F. Brown; R. Loosli; P. Schmid-Hempel; Condition-dependent expression of virulence in a trypanosome infecting bumblebees. Oikos 2000, 91, 421-427, 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.910302.x.

- Ben Sadd; Seth Barribeau; Heterogeneity in infection outcome: lessons from a bumblebee-trypanosome system. Parasite Immunology 2013, 35, 339-49, 10.1111/pim.12043.

- Hauke Koch; James Woodward; Moses K. Langat; Mark J.F. Brown; Philip Stevenson; Flagellum Removal by a Nectar Metabolite Inhibits Infectivity of a Bumblebee Parasite. Current Biology 2019, 29, 3494-3500.e5, 10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.037.

- Nathalie Roger; Denis Michez; Ruddy Wattiez; Christopher Sheridan; Maryse Vanderplanck; Diet effects on bumblebee health. Journal of Insect Physiology 2017, 96, 128-133, 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2016.11.002.

- Arran J. Folly; Philip Stevenson; Mark J. F. Brown; Age-related pharmacodynamics in a bumblebee-microsporidian system mirror similar patterns in vertebrates. Journal of Experimental Biology 2020, 223, jeb217828, 10.1242/jeb.217828.

- Evan C Palmer-Young; Cansu Ozge Tozkar; Ryan S Schwarz; Yanping Chen; Rebecca E Irwin; Lynn S Adler; Jay D Evans; Nectar and Pollen Phytochemicals Stimulate Honey Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Immunity to Viral Infection. Journal of Economic Entomology 2017, 110, 1959-1972, 10.1093/jee/tox193.

- Jonathan J. Giacomini; Jessica Leslie; David Tarpy; Evan C. Palmer-Young; Rebecca E. Irwin; Lynn S. Adler; Medicinal value of sunflower pollen against bee pathogens. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 1-10, 10.1038/s41598-018-32681-y.

- George M. LoCascio; Luis Aguirre; Rebecca E. Irwin; Lynn S. Adler; Pollen from multiple sunflower cultivars and species reduces a common bumblebee gut pathogen. Royal Society Open Science 2019, 6, 190279, 10.1098/rsos.190279.

- George M. LoCascio; River Pasquale; Eugene Amponsah; Rebecca E. Irwin; Lynn S. Adler; Effect of timing and exposure of sunflower pollen on a common gut pathogen of bumble bees. Ecological Entomology 2019, 44, 702-710, 10.1111/een.12751.

- Alison E. Fowler; Elyse C. Stone; Rebecca E. Irwin; Lynn S. Adler; Sunflower pollen reduces a gut pathogen in worker and queen but not male bumble bees. Ecological Entomology 2020, 45, 1318-1326, 10.1111/een.12915.

- Jonathan J. Giacomini; Sara J. Connon; Daniel Marulanda; Lynn S. Adler; Rebecca E. Irwin; The costs and benefits of sunflower pollen diet on bumble bee colony disease and health. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03663, 10.1002/ecs2.3663.

- Lynn S. Adler; Alison E. Fowler; Rosemary L. Malfi; Patrick R. Anderson; Lily M. Coppinger; Pheobe M. Deneen; Stephanie Lopez; Rebecca E. Irwin; Iain W. Farrell; Philip C. Stevenson; et al. Assessing Chemical Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Sunflower Pollen on a Gut Pathogen in Bumble Bees. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2020, 46, 649-658, 10.1007/s10886-020-01168-4.

- Jonathan J. Giacomini; Nicholas Moore; Lynn S. Adler; Rebecca E. Irwin; Sunflower pollen induces rapid excretion in bumble bees: Implications for host-pathogen interactions. Journal of Insect Physiology 2022, 137, 104356, 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2022.104356.

- Marwa Roumani; Sébastien Besseau; David Gagneul; Christophe Robin; Romain Larbat; Phenolamides in plants: an update on their function, regulation, and origin of their biosynthetic enzymes. Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 72, 2334-2355, 10.1093/jxb/eraa582.

- Carolina Elejalde-Palmett; Thomas Dugé De Bernonville; Gaëlle Glevarec; Olivier Pichon; Nicolas Papon; Vincent Courdavault; Benoit St-Pierre; Nathalie Giglioli-Guivarc’H; Arnaud Lanoue; Sébastien Besseau; et al. Characterization of a spermidine hydroxycinnamoyltransferase inMalus domesticahighlights the evolutionary conservation of trihydroxycinnamoyl spermidines in pollen coat of core Eudicotyledons. Journal of Experimental Botany 2015, 66, 7271-7285, 10.1093/jxb/erv423.

- Thomas Vogt; Unusual spermine-conjugated hydroxycinnamic acids on pollen: function and evolutionary advantage. Journal of Experimental Botany 2018, 69, 5311-5315, 10.1093/jxb/ery359.

- D. Sammataro; E. H. Erickson; M. B. Garment; Ultrastructure of the Sunflower Nectary. Journal of Apicultural Research 1985, 24, 150-160, 10.1080/00218839.1985.11100665.

- Daniel Cook; Jessamyn S. Manson; Dale R. Gardner; Kevin D. Welch; Rebecca E. Irwin; Norditerpene alkaloid concentrations in tissues and floral rewards of larkspurs and impacts on pollinators. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2013, 48, 123-131, 10.1016/j.bse.2012.11.015.

- Thomas Stegemann; Lars H. Kruse; Moritz Brütt; Dietrich Ober; Specific Distribution of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids in Floral Parts of Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) and its Implications for Flower Ecology. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2018, 45, 128-135, 10.1007/s10886-018-0990-9.

- Susan Wendy Nicolson; Hannelie Human; Chemical composition of the ‘low quality’ pollen of sunflower (Helianthus annuus, Asteraceae). Apidologie 2012, 44, 144-152, 10.1007/s13592-012-0166-5.

- Maryse Vanderplanck; Hélène Gilles; Denis Nonclercq; Pierre Duez; Pascal Gerbaux; Asteraceae Paradox: Chemical and Mechanical Protection of Taraxacum Pollen. Insects 2020, 11, 304, 10.3390/insects11050304.

- Stephen Blackmore; Alexandra H. Wortley; John J. Skvarla; John R. Rowley; Pollen wall development in flowering plants. New Phytologist 2007, 174, 483-498, 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02060.x.

- Ombeline Sculfort; Maxence Gérard; Antoine Gekière; Denis Nonclercq; Pascal Gerbaux; Pierre Duez; Maryse Vanderplanck; Specialized Metabolites in Floral Resources: Effects and Detection in Buff-Tailed Bumblebees. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 9, 669352, 10.3389/fevo.2021.669352.

- Jan Kyselka; Roman Bleha; Miroslav Dragoun; Kristýna Bialasová; Šárka Horáčková; Martin Schätz; Marcela Sluková; Vladimír Filip; Andriy Synytsya; Antifungal Polyamides of Hydroxycinnamic Acids from Sunflower Bee Pollen. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2018, 66, 11018-11026, 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03976.

- Mari-Anne Newman; Edda Von Roepenack-Lahaye; Adrian Parr; Michael J. Daniels; J. Maxwell Dow; Induction of Hydroxycinnamoyl-Tyramine Conjugates in Pepper by Xanthomonas campestris, a Plant Defense Response Activated by hrp Gene-Dependent and hrp Gene-Independent Mechanisms. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2001, 14, 785-792, 10.1094/mpmi.2001.14.6.785.

- Waldan K. Kwong; Nancy A. Moran; Gut microbial communities of social bees. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2016, 14, 374-384, 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.43.

- Sarah Chahine; Michael J. O'Donnell; Interactions between detoxification mechanisms and excretion in Malpighian tubules ofDrosophila melanogaster. Journal of Experimental Biology 2011, 214, 462-468, 10.1242/jeb.048884.

- Estela L. Arrese; Jose L. Soulages; Insect Fat Body: Energy, Metabolism, and Regulation. Annual Review of Entomology 2010, 55, 207-225, 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085356.

- Yu, S.J.. Detoxification mechanisms in insects; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1252–1254.

- Maxence Gerard; Denis Michez; Vincent Debat; Lovina Fullgrabe; Ivan Meeus; Niels Piot; Ombeline Sculfort; Martin Vastrade; Guy Smagghe; Maryse Vanderplanck; et al. Stressful conditions reveal decrease in size, modification of shape but relatively stable asymmetry in bumblebee wings. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 15169, 10.1038/s41598-018-33429-4.

- Deanna Beasley; Andrea Bonisoli Alquati; Timothy A. Mousseau; The use of fluctuating asymmetry as a measure of environmentally induced developmental instability: A meta-analysis. Ecological Indicators 2013, 30, 218-226, 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.02.024.

- Vincent Debat; Patrice David; Mapping phenotypes: canalization, plasticity and developmental stability. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2001, 16, 555-561, 10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02266-2.

- Anders Pape Møller; A review of developmental instability, parasitism and disease: Infection, genetics and evolution. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2006, 6, 133-140, 10.1016/j.meegid.2005.03.005.

- Schmid-Hempel, P.; Wilfert, L.; Schmid-Hempel, R. . Pollinator diseases: The Bombus-Crithidia system; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 3-31.

- Leif L. Richardson; Lynn S. Adler; Anne S. Leonard; Jonathan Andicoechea; Karly Regan; Winston E. Anthony; Jessamyn S. Manson; Rebecca E. Irwin; Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumblebees. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 282, 20142471-20142471, 10.1098/rspb.2014.2471.

- M. J. F. Brown; Y. Moret; P. Schmid-Hempel; Activation of host constitutive immune defence by an intestinal trypanosome parasite of bumble bees. Parasitology 2003, 126, 253-260, 10.1017/s0031182002002755.

- Arran J. Folly; Hauke Koch; Philip C. Stevenson; Mark J.F. Brown; Larvae act as a transient transmission hub for the prevalent bumblebee parasite Crithidia bombi. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 2017, 148, 81-85, 10.1016/j.jip.2017.06.001.

- Alison E. Fowler; Jonathan J. Giacomini; Sara June Connon†; Rebecca E. Irwin; Lynn S. Adler; Sunflower pollen reduces a gut pathogen in the model bee species, Bombus impatiens , but has weaker effects in three wild congeners. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2022, 289, 1318-1326, 10.1098/rspb.2021.1909.

- Blair K. Mockler; Waldan K. Kwong; Nancy A. Moran; Hauke Koch; Microbiome Structure Influences Infection by the Parasite Crithidia bombi in Bumble Bees. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2018, 84, 1-11, 10.1128/aem.02335-17.

- Jean-Etienne Bassard; Pascaline Ullmann; François Bernier; Danièle Werck-Reichhart; Phenolamides: Bridging polyamines to the phenolic metabolism. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1808-1824, 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.08.003.

- David Baracchi; Lukas P. Thorburn; Lynn S. Adler; Rebecca E. Irwin; Evan C. Palmer-Young; Referee report. For: Variable effects of nicotine and anabasine on parasitized bumble bees [version 1; referees: 2 approved with reservations]. F1000Research 1970, 4, 880, 10.5256/f1000research.7396.r10860.

- Jessica Abbott; Self-medication in insects: current evidence and future perspectives. Ecological Entomology 2014, 39, 273-280, 10.1111/een.12110.

- Jacobus C de Roode; Mark Hunter; Self-medication in insects: when altered behaviors of infected insects are a defense instead of a parasite manipulation. Current Opinion in Insect Science 2018, 33, 1-6, 10.1016/j.cois.2018.12.001.