CAFs are heterogeneous in terms of their origin in different organ-type cancers, as well as in the progression of the disease. The heterogeneous subpopulations of CAFs, such as myoblastic CAFs (myCAFs) and inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), have been extensively studied in fibroinflammatory PDAC disease characterized by dense and highly proliferating desmoplastic stroma. In fact, Li et al. identified genes associated with the differentiation of myCAFs and iCAFs [

22,

23,

24]. Adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs) have been shown to possess a high multilineage potential and self-renewal capacity and were reported as the CAF sources in PDAC by Miyazaki et al. [

24]. Their study identified that AD-MSCs could differentiate into distinct CAF subtypes, myCAFs and iCAFs, depending on the different co-culture conditions in vitro. The diverse functions of iCAFs and myCAFs have also been reported in cholangiocarcinoma; breast cancers; prostate, head, and neck squamous cell carcinoma; and bladder and colon cancers. The diversity of CAF subpopulations was also recently reported to promote the growth of cholangiocarcinoma, wherein hepatic stellate cells (HSC) are the primary cause of CAF differentiation into myCAFs and iCAFs [

25]. The hyaluronan synthase 2 myCAFs, but not type I collagen-expressing myCAFs, promoted tumor progression, while HGF-expressing iCAFs enhanced tumor growth via tumor-expressed MET, thereby directly linking CAFs to tumor cells. Another subset of CAFs, FAP+CAFs, were identified by Kieffer et al. in breast cancers that mediated immunosuppression and immunotherapy resistance via a positive feedback loop between specific CAF-S1 clusters and Tregs [

26]. In prostate cancer, a differential mode of activation of iCAFs and myCAFs has been reported [

27]. IL-1a/ELF3/YAP pathways are involved in iCAF differentiation, while TGF-beta1 induces myCAFs. One of the ways CAFs classically interact with the tumor cell EMT function was reported by Goulet et al. in bladder cancer, where IL-6 cytokine was found to be highly expressed in iCAFs, and its receptor IL-6R was found on RT4 bladder cancer cells [

28]. Perhaps the most intriguing functional heterogeneity of CAFs was reported by Pan et al. in PDAC-CAF-exhibited organ-specific metastatic potential leading to different levels of heterogeneity of CAFs in different metastatic niches [

29]. Several cell signaling pathways have been reported to be involved in the functioning of iCAFs and myCAFs, including the Hedgehog pathway [

30]; Wnt pathway [

31]; integrin a11B1 signaling [

32]; cMET-HGF pathway [

25]; IL-6 signaling [

28]; EMT signaling via transcription factors SNAIL1, TWIST1, and ZEB1 [

28]; and IL1B-mediated crosstalk [

33]. Recently, Steele et al. reported that the Hedgehog pathway acts in a paracrine manner in PDAC, with ligands secreted by tumor cells signaling to stromal CAFs. The Hedgehog pathway activation is higher in PDPN+ alphaSMA+ myCAFs compared with iCAFs, and its inhibition impairs tumor growth by altering the fibroblast compartment in PDAC. Hedgehog pathway inhibition resulted in a reduction in myCAF numbers and a significant expansion of iCAFs, leading to an increase in the iCAF/myCAF ratio. As iCAFs are a source of inflammatory signals, the authors observed an increase in iCAFs upon Hedgehog inhibition, which correlated with changes in immune infiltration (significantly decreased CD8+ T cells and increased CD4+ T cells and CD25+CD4+ T cells; abundant FOXP3+ regulatory T cells) that are consistent with a more immunosuppressive pancreatic cancer microenvironment. The paracrine activation differentially elevated myCAFs compared with iCAFs, leading to favorable alterations of cytotoxic T cells and Tregs, causing increased immunosuppression [

30]. Wnt signaling in CAFs represents a non-cell-autonomous mechanism for colon cancer progression [

31]. Mose et al. reported Sfrp1 epithelial–mesenchymal transition phenotype induction in tumor cells without affecting tumor-intrinsic Wnt signaling, suggesting involvement of non-immune stromal cells. Low levels of Wnt signals induced the iCAF subtype, which in co-culture with organoids induced EMT, whereas high levels induced contractile myCAFs to attenuate the EMT phenotype.

The tumors with (1) an accumulation of stromal CAFs, (2) the presence of fibrotic stroma, (3) a high expression level of stroma signature genes, or (4) a high tumor/stroma ratio in the primary tumor are associated with poor prognosis in various cancers, including colon, gastric, esophagus, breast, NSCLC (non-small cell lung cancer), and liver cancers [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. It is understood that chemotherapy’s limited effect (benefit) and the progression or recurrence of disease through therapy in many solid tumors are attributed to the development of resistance within tumor cells in support of the stroma. As a dominant component of tumor stroma, CAFs interact with both a tumor cell and the TME. The versatility of CAF functions and their several modes of interaction with tumor cells and all components of stroma (ECM and cells of the TME) indicate that a metastasis or progression of disease following treatment is aided and abetted by CAFs. Once a therapy-resistive circuitry is established between tumor cells and the CAFs of the stroma, tumor-centric therapy alone essentially becomes insufficient.

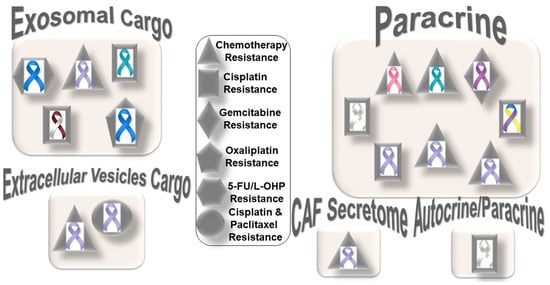

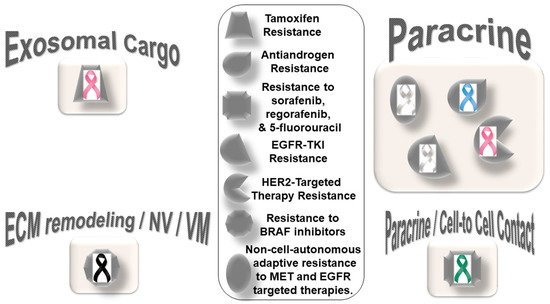

Figure 1 presents the distribution pattern of the types of resistance to chemotherapy based on specific mediators of CAF functions in solid tumors. The four types of mediators of action employed by CAFs to orchestrate the development of resistance to chemotherapy are presented in the cartoon. The most common mode of interaction is a paracrine, wherein CAFs signal to either tumor cells or other components of the TME via characteristic secretomes. In addition to the involvement of characteristic secretomes, exosomal cargos delivering different miRNAs that target various cell signaling proteins are common mediators of CAFs. The paracrine mode of action of CAFs is the predominant form of action, represented by six types of organ tumors (organ tumors are indicated by their respective ribbon colors, as presented in the figure legends). CAF crosstalk with tumor cells, and the TME occurs via exosomal cargo, imparting resistance to four organ cancers. The extracellular vesicle, secretome, and autocrine or paracrine modes are much less involved in the modes of action (

Figure 1). The sizes of the boxes indicate the number of studies in each box. Among resistance to different types of chemotherapies, cisplatin resistance has been found to be very common, which is involved in both paracrine and exosomal cargo modes of action (the shapes in the inset indicate the types of resistances in different tumors).

Among the different types of solid tumors, gastric cancers have been reported to be the most common tumors exhibiting CAF-mediated resistance to chemotherapy, which involve paracrine, exosomal cargo, extracellular vesicle, and secretomic modes of action. Secretion of IL-11 from CAFs activated the IL-11/IL-11R/gp130/JAK/STAT3/Bcl anti-apoptosis signaling pathway in gastric cancer cells. Thus, CAF-derived IL-11 secretion caused resistance to chemotherapy regimens in gastric cancers [

41]. In another study, CAF-induced activation of the JAK-STAT signaling has been proposed to confer chemoresistance in gastric cancer cells, while interleukin-6 (IL-6) was identified as a CAF-specific secretory protein that protects gastric cancer cells via paracrine signaling. Interestingly, clinical data have shown that IL-6 was differentially expressed in the stromal portion of cancer tissues, while IL-6 upregulation was positively correlated with poor responsiveness to chemotherapy [

42]. In line with the above facts, several CAF-targeting agents have been tested in experimental models, as reviewed elsewhere [

43]. Resistance to conventional chemotherapeutics in gastric cancers has been reported to be mediated by CAF-derived extracellular vesicles [

44]. Annexin A6 initiated network formation and drug resistance within the ECM via activation of beta1 integrin-FAK-YAP signaling. Annexin A6 within CAF extracellular vesicles has been shown to stimulate FAK-YAP signaling by stabilizing beta1 integrin at the cell surface of gastric cancer cells, which subsequently induces drug resistance. In addition to extracellular vesicles, CAFs also communicate via exosomal cargos, which carry miRNAs and mediate resistance to specific chemotherapeutic agents, as presented in the following section.