Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biology

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is driven by chronic liver diseases that exhibit several rounds of liver inflammation, necrosis, and regeneration making, HCC a paradigm for inflammation-driven cancer. The role of viral and non-viral inflammation in genetic perturbation and chromosomal aberration predisposing HCC is well-characterized. Instead, the focus of the entry is to summarize the impact of viral hepatitis-mediated immune deregulation on the development and progression of HCC.

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- hepatitis B virus

1. The Role of HBV-Related Immunity in the Development of HCC

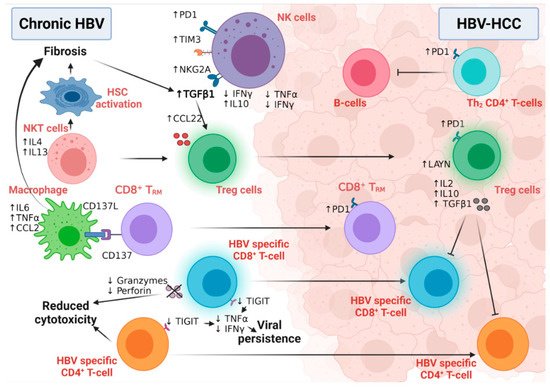

HBV is a non-cytopathic virus, and the degree of liver damage in chronic HBV infection is driven by the activation of the immune system [1]. The interplay between immune tolerance and immune clearance predicts the progression of chronic HBV disease (Figure 1) [1]. HBV-induced immune deregulation in chronic settings is a fertile niche for the development of HCC.

Figure 1. The interplay between different immune cells in HBV-HCC. NK cells in chronic HBV infection and HBV-HCC express different inhibitory receptors and secrete many fibrogenic and proinflammatory cytokines that participate in disease progression. While NKT cells stimulate hepatic stellate cell activation in chronic HBV patients, macrophages also induce fibrosis via interaction with CD8+TRM. HBV-specific CD8+T and CD4+T-cells lose their cytolytic activity and eradicate neither HBV infection nor the HBV-HCC tumor cells. Moreover, Tregs induce their immunotolerant role in both chronic infection and HCC, leading to disease progression and aggressiveness. Figure created with BioRender.com.

1.1. Innate Immunity and HCC Development

Active mature NK cells have critical antiviral and anti-tumor functional roles [2]; however, an NK cell’s switch to a less active and immature phenotype, confirmed by low cytolytic and low IFNγ production, was detected during HBV chronic infection and HBV-HCC. HBV viral persistence and HBV-induced liver fibrosis upregulated the expression of IL10 and TGF-β immunosuppressive cytokines to dampen the immune surveillance role of NK cells [3], while inducing the expression microRNA-146a in these NK cells [4]. This microRNA-146a induced the further feed-forward inactivation of NK function, as measured by the inhibition of IFNγ and TNFα production in chronic HBV and HBV-HCC patients [4]. In addition, the overexpression of the inhibitory receptors PD-1, TIM3, and NKG2A in NK cells of chronically infected HBV patients predispose them to HCC [5]. Intriguingly, active NK cells may also contribute to hepatocyte damage and HCC development via the IFNγ-dependent activation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in HB transgenic mice [6], suggesting the importance of immune balance in the fight against HCC [7]. Although NKT cells are not directly associated with HBV-HCC development, they predispose one to malignancy via the induction of liver fibrosis [8]. NKT cells secrete IL4 and IL13 cytokines, activating hepatic liver stellate cells in HBV-transgenic mice [8]. Macrophages play both anti-tumor and tumor roles in HCC development and progression due to their high plasticity and versatile functions [9]. CD137 ligand was found to be upregulated in peripheral monocytes of chronic HBV patients with positive association with cirrhosis [10]. The further investigation of this finding in HBV-transgenic mice revealed the upregulation of CD137 on the surface of the non-specific CD8+ memory T-cells, which, in turn, enhanced the recruitment of macrophages to murine livers. Macrophages induced disease progression to liver fibrosis and HCC via the production of TNFα, IL6, and MCP-1 [10].

1.2. Adaptive Immunity and HCC Development

The transition of active CD8+ T-cells into the exhausted phenotype (characterized by high levels of PD1, CTLA4, and TIM3) is a unique feature of viral persistence and disease progression (Figure 1) [11]. Moreover, in HBV-HCC, the HBV-mediated activation of the STAT3 pathway induced the expression of the oncogene SALL4, which consequently inhibited the expression of microRNA 200c [12]. This microRNA 200c inhibition induced the expression of PDL1, which initiated CD8+ T-cell exhaustion [12]. The high-resolution single-cell sequencing of human HBV-HCC confirmed the presence of two distinct T-cell subtypes within the tumor microenvironment: CD8+ resident memory T cells (TRM) and Treg cells [13]. TRM cells expressed high levels of PD1 and were more suppressive and exhausted, while Treg cells expressed the immunosuppressive LAYN protein [13]. HBV patients with the immune-tolerant phenotype showed a high susceptibility to develop HCC compared to immune active HBV patients, confirming the hypothesis that the presence of HBV-specific CD8+T-cells that are functionally unable to remove the virus induced continuous inflammation followed by tumor development [14]. In line with this, we have also shown evidence of HBV-DNA integration and clonal hepatocyte expansion in these patients considered immune-tolerant, indicating that hepatocarcinogenesis could be underway even in the early stages of HBV [15]. Moreover, in those subjects deemed as having immune control, evidence of HBV-DNA integration is again present, with the upregulation of genes involved in carcinogenesis [16]. The link between immunity and HBV DNA integration, however, remains tenuous, but with the use of novel technologies (e.g., tissue CyTOF and spatial transcriptomics) we can come to understand more about this relationship in the future. How functionally incompetent CD8 still leads to continuous inflammation is a complex process. Previous studies by Maini et al. have demonstrated that this may be an indirect pathway, where virus-specific CD8 T cells that were unable to control infection led to the recruitment of non-virus specific T cells to the liver, which could drive liver pathology [17]. More recently, further studies have demonstrated that exhausted CD8 cells in human chronic infections and animal models are heterogenous and can be identified by phenotypic and transcriptional markers— e.g., PD1 and TCF1—differentiating them between early and terminally exhausted CD8 T cells [17][18]. The balance of these heterogenous populations may also impact on the associated continuous inflammation. A further animal study demonstrated that the recovery of the immune response may be possible via the specific blockade of the check-point receptor TIGIT and overcoming T cell tolerance to HBsAg, but the consequences are increased liver inflammation and the development of liver tumors [19]. Although the loss of CD4+ T-cells in chronic HBV infection was associated with suboptimal HBV-specific CD8+ T-cell function and viral persistence [20], the number of circulating and liver-recruited CD4+ CTLs increased in the early stages of human HBV-HCC [21]. This T-cell population was reduced and malfunctioned with increasing disease stage, possibly due to the increased infiltration of Treg cells; this loss of CD4+ CTLs was associated with poor patient outcomes [21]. This finding supports the notion that the intra-tumoral immune profile is completely different from immunity developed in the corresponding benign liver disease [22][23]. HBV-HCC is usually preceded by liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, which are characterized by the fibrogenic TGFβ pathway signature [24]. The activation of the TGFβ pathway suppressed the expression of microRNA 34a, leading to the upregulation of the Treg-recruiting cytokine CCL22 [24]. Increased Treg recruitment in HBV-HCC patients was associated with poor prognosis and portal vein thrombosis [24]. Treg cells suppressed the function of effector T-cells via the production of immunosuppressive cytokines, including, but not limited to, IL2, 1L10, and TGFβ [25]. Compared to non-viral HCC, the Tregs detected in HBV-HCC uniquely expressed PD-1, which exhausted functional CD8+ T- cells (as marked by low granzyme A/B and perforin and blunted proliferation) within the tumor microenvironment [13][26], explaining the reduced sensitivity of the non-viral HCC to PD1 treatment [27].

CD4+ T-follicular helper cells are a unique anti-tumor immune subset responsible for the activation and maturation of B-cells and B-cell-mediated immunity [28]. The number and functional capacity of the circulating CXCR5+CD4+ Tfh cells were reduced in patients with HBV-HCC compared to diseased and healthy controls [29][30]. Furthermore, a similar dysregulated pattern was seen relative to the disease stage, as confirmed by low IL21, IL10, and ICOS expression [29][30].

The mechanism of Hepatocarcinogenesis with HDV-HBV co-infection can be mediated via innate and adaptive immune responses as well as epigenetic- and metabolic-related changes. The L-HDAg may facilitate several interactions with signaling pathways involved in survival and apoptosis and promote oxidative stress in the ER. Epigenetic modifications (e.g., histone acetylation and clusterin expression) may aid in HDV-infected cell survival in cancerous cells [31][32].

2. The Role of HCV-Related Immunity in the Development of HCC

HCV viral persistence promotes immune perturbation in the liver microenvironment through the inhibition of interferon signaling, the skewing of CD4+T-cell differentiation towards more hazardous phenotypes, the recruitment of immunosuppressive Treg cells into the liver, and the deactivation of the cytotoxic CD8+T-cells. Low-grade chronic inflammation then develops, along with fibrotic and cirrhotic changes with high tumor escape possibilities, altered immune surveillance, and eventually HCC.

2.1. Innate Immunity and HCC Development

Following HCV infection, the NF-kB and IFN signaling pathways are activated in NK cells [33]. The first evidence that linked NF-kB pathway activation and HCC development was from a mouse model of chronic liver inflammation in which NF-kB activation in non-parenchymal cells contributed to the tumor burden [34]. Tumor development in this murine model was closely associated with the release of different proinflammatory and protumorigenic cytokines such as TNFα and IL6 [34]. The activation of NF-kB and HCC development is likely to be etiology-independent with our team developing a new dietary-induced HCC experimental model that showed NF-kB activation in the non-tumor tissue of mice developing HCC [35]. IL6 has also been shown to contribute to hepatocarcinogenesis and a study in HCV patients suggested that this may be gender dependent. Unlike male patients, serum IL6 levels in chronic HCV female patients were associated with a high risk of HCC development, linking IL6 levels and gender-related hepatocarcinogenesis [36]. HCV also activated STAT3 pathway in human monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells in an IL6-dependent manner [37]. Interestingly, a seminal transcriptomic study in HCC patients identified a unique association between NF-kB and STAT3 activation in the adjacent non-tumor tissue, but not the tumor counterparts, and HCC recurrence [38], emphasizing the pivotal role of these pathways in tumor progression and relapse. Additionally, NS5A activates the NF-kB and JNK pathways through TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) [39]. In fact, JNK pathway activation in the non-parenchymal cells was linked with HCC development in experimental mouse models [40]. Furthermore, a large body of evidence associates the activation of the IFN pathway and tumor development [41], whilst lower levels of IL10 cytokine were detected in the sera of HCV-HCC, suggesting that further studies are required to assess whether IL10 supports anti-tumor immunity [42].

2.2. Adaptive Immunity and HCC Development

Similar to HBV infection, chronic HCV infection increases the production of lymphotoxin (LT) α and β cytokines and their receptor (LTβR) in hepatocytes. This upregulation led to the increased infiltration of several lymphocytic subsets preceding the development of HCC [43]. A multi-center study of HCV-HCC patients witnessed a high infiltration of CD4+T-cells and Treg cells in the fibrous septa and the accumulation of CD8+T-cells in the cirrhotic nodules compared to cirrhotic HCV patients. This latter population was associated with decreased levels of NK and NKT cells and with a high risk of tumor recurrence [44]. In contrast, a high prevalence of Treg cells in the peri-tumoral area contributed to an aggressive tumor phenotype [45]. The presence of tumor-associated antigens and tumor-specific mutant antigens is common in HCC [46]. Tumor-associated antigens are recognized and depleted by their specific CD8+T-cells. This interaction was associated with longer survival and better patient outcomes [47]. However, constant CD8+T-cell exposure to these antigens induced T-cell exhaustion in HCV chronic infection and HCV-HCC [48]. This leaves the door open for the best combination therapy for HCC patients from different etiologies, especially with the lack of significant success of monotherapy with PD1 checkpoint inhibitors in many HCC clinical trials.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14051255

References

- Levrero, M.; Zucman-Rossi, J. Mechanisms of HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, S84–S101.

- He, Y.; Tian, Z. NK cell education via nonclassical MHC and non-MHC ligands. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 14, 321–330.

- Peppa, D.; Micco, L.; Javaid, A.; Kennedy, P.T.F.; Schurich, A.; Dunn, C.; Pallant, C.; Ellis, G.; Khanna, P.; Dusheiko, G.; et al. Blockade of Immunosuppressive Cytokines Restores NK Cell Antiviral Function in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001227.

- Xu, D.; Han, Q.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. miR-146a negatively regulates NK cell functions via STAT1 signaling. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 14, 712–720.

- Marraco, S.A.F.; Neubert, N.; Verdeil, G.; Speiser, D. Inhibitory Receptors Beyond T Cell Exhaustion. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 310.

- Chen, Y.; Hao, X.; Sun, R.; Wei, H.; Tian, Z. Natural Killer Cell–Derived Interferon-Gamma Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Through the Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule–Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Axis in Hepatitis B Virus Transgenic Mice. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1735–1750.

- Maini, M.K.; Peppa, D. NK Cells: A Double-Edged Sword in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 57.

- Jin, Z.; Sun, R.; Wei, H.; Gao, X.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Z. Accelerated liver fibrosis in hepatitis B virus transgenic mice: Involvement of natural killer T cells. Hepatology 2010, 53, 219–229.

- Wynn, T.A.; Vannella, K.M. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 2016, 44, 450–462.

- Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Cheng, L.; Guo, M.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Tan, Y.; Ma, S.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; et al. CD137-Mediated Pathogenesis from Chronic Hepatitis to Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Hepatitis B Virus-Transgenic Mice. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 7654–7662.

- Boni, C.; Fisicaro, P.; Valdatta, C.; Amadei, B.; Di Vincenzo, P.; Giuberti, T.; Laccabue, D.; Zerbini, A.; Cavalli, A.; Missale, G.; et al. Characterization of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)-Specific T-Cell Dysfunction in Chronic HBV Infection. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4215–4225.

- Sun, C.; Lan, P.; Han, Q.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, G.; Song, J.; Wang, J.; Wei, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. Oncofetal gene SALL4 reactivation by hepatitis B virus counteracts miR-200c in PD-L1-induced T cell exhaustion. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–17.

- Lim, C.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Pan, L.; Lai, L.; Chua, C.; Wasser, M.; Lim, T.K.H.; Yeong, J.; Toh, H.C.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Multidimensional analyses reveal distinct immune microenvironment in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2018, 68, 916–927.

- Kim, G.-A.; Lim, Y.-S.; Han, S.; Choi, J.; Shim, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Lee, H.C.; Lee, Y.S. High risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and death in patients with immune-tolerant-phase chronic hepatitis B. Gut 2017, 67, 945–952.

- Mason, W.S.; Gill, U.S.; Litwin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Peri, S.; Pop, O.; Hong, M.; Naik, S.; Quaglia, A.; Bertoletti, A.; et al. HBV DNA Integration and Clonal Hepatocyte Expansion in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients Considered Immune Tolerant. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 986–998.e4.

- Svicher, V.; Salpini, R.; Piermatteo, L.; Carioti, L.; Battisti, A.; Colagrossi, L.; Scutari, R.; Surdo, M.; Cacciafesta, V.; Nuccitelli, A.; et al. Whole exome HBV DNA integration is independent of the intrahepatic HBV reservoir in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Gut 2021, 70, 2337–2348.

- Maini, M.; Boni, C.; Lee, C.K.; Larrubia, J.; Reignat, S.; Ogg, G.S.; King, A.S.; Herberg, J.; Gilson, R.; Alisa, A.; et al. The Role of Virus-Specific Cd8+ Cells in Liver Damage and Viral Control during Persistent Hepatitis B Virus Infection. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 191, 1269–1280.

- Heim, K.; Neumann-Haefelin, C.; Thimme, R.; Hofmann, M. Heterogeneity of HBV-Specific CD8+ T-Cell Failure: Implications for Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2240.

- Zong, L.; Peng, H.; Sun, C.; Li, F.; Zheng, M.; Chen, Y.; Wei, H.; Sun, R.; Tian, Z. Breakdown of adaptive immunotolerance induces hepatocellular carcinoma in HBsAg-tg mice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 221.

- Asabe, S.; Wieland, S.F.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Roederer, M.; Engle, R.; Purcell, R.H.; Chisari, F.V. The Size of the Viral Inoculum Contributes to the Outcome of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 9652–9662.

- Fu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Qi, Z.; Xing, S.; Lv, J.; Shi, J.; Fu, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.-Y.; et al. Impairment of CD4+cytotoxic T cells predicts poor survival and high recurrence rates in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2012, 58, 139–149.

- Moeini, A.; Torrecilla, S.; Tovar, V.; Montironi, C.; Andreu-Oller, C.; Peix, J.; Higuera, M.; Pfister, D.; Ramadori, P.; Pinyol, R.; et al. An Immune Gene Expression Signature Associated With Development of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Identifies Mice That Respond to Chemopreventive Agents. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 1383–1397.e11.

- Sia, D.; Jiao, Y.; Martinez-Quetglas, I.; Kuchuk, O.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; de Moura, M.C.; Putra, J.; Campreciós, G.; Bassaganyas, L.; Akers, N.; et al. Identification of an Immune-specific Class of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Based on Molecular Features. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 812–826.

- Yang, P.; Li, Q.-J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Markowitz, G.J.; Ning, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, S.; Yuan, Y.; et al. TGF-β-miR-34a-CCL22 Signaling-Induced Treg Cell Recruitment Promotes Venous Metastases of HBV-Positive Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 291–303.

- Trehanpati, N.; Vyas, A.K. Immune Regulation by T Regulatory Cells in Hepatitis B Virus-Related Inflammation and Cancer. Scand. J. Immunol. 2017, 85, 175–181.

- Fu, J.; Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Shi, M.; Zhao, P.; Fu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, C.; et al. Increased Regulatory T Cells Correlate With CD8 T-Cell Impairment and Poor Survival in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2328–2339.

- Pfister, D.; Núñez, N.G.; Pinyol, R.; Govaere, O.; Pinter, M.; Szydlowska, M.; Gupta, R.; Qiu, M.; Deczkowska, A.; Weiner, A.; et al. NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature 2021, 592, 450–456.

- Tangye, S.G.; Ma, C.; Brink, R.; Deenick, E.K. The good, the bad and the ugly—TFH cells in human health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 412–426.

- Zhou, Z.-Q.; Tong, D.-N.; Guan, J.; Tan, H.-W.; Zhao, L.-D.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.-Y. Follicular helper T cell exhaustion induced by PD-L1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma results in impaired cytokine expression and B cell help, and is associated with advanced tumor stages. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 2926–2936.

- Jia, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Jin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.-S. Impaired Function of CD4+ T Follicular Helper (Tfh) Cells Associated with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117458.

- Liao, F.-T.; Lee, Y.-J.; Ko, J.-L.; Tsai, C.-C.; Tseng, C.-J.; Sheu, G.-T. Hepatitis delta virus epigenetically enhances clusterin expression via histone acetylation in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1124–1134.

- Choi, S.; Jeong, S.; Hwang, S.B. Large Hepatitis Delta Antigen Modulates Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling Cascades: Implication of Hepatitis Delta Virus–Induced Liver Fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 343–357.

- Rehermann, B. Pathogenesis of chronic viral hepatitis: Differential roles of T cells and NK cells. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 859–868.

- Pikarsky, E.; Porat, R.M.; Stein, I.; Abramovitch, R.; Amit, S.; Kasem, S.; Gutkovich-Pyest, E.; Urieli-Shoval, S.; Galun, E.; Ben-Neriah, Y. NF-κB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature 2004, 431, 461–466.

- Zaki, M.Y.W.; Mahdi, A.K.; Patman, G.L.; Whitehead, A.; Maurício, J.P.; McCain, M.V.; Televantou, D.; Abou-Beih, S.; Ramon-Gil, E.; Watson, R.; et al. Key features of the environment promoting liver cancer in the absence of cirrhosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–17.

- Nakagawa, H.; Maeda, S.; Yoshida, H.; Tateishi, R.; Masuzaki, R.; Ohki, T.; Hayakawa, Y.; Kinoshita, H.; Yamakado, M.; Kato, N.; et al. Serum IL-6 levels and the risk for hepatocarcinogenesis in chronic hepatitis C patients: An analysis based on gender differences. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 2264–2269.

- Tacke, R.S.; Tosello-Trampont, A.; Nguyen, V.; Mullins, D.W.; Hahn, Y.S. Extracellular Hepatitis C Virus Core Protein Activates STAT3 in Human Monocytes/Macrophages/Dendritic Cells via an IL-6 Autocrine Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 10847–10855.

- Hoshida, Y.; Villanueva, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Peix, J.; Chiang, D.Y.; Camargo, A.; Gupta, S.; Moore, J.; Wrobel, M.J.; Lerner, J.; et al. Gene Expression in Fixed Tissues and Outcome in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1995–2004.

- Park, K.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Choi, D.-H.; Park, J.-M.; Yie, S.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Hwang, S.B. Hepatitis C Virus NS5A Protein Modulates c-Jun N-terminal Kinase through Interaction with Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-associated Factor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 30711–30718.

- Das, M.; Garlick, D.S.; Greiner, D.L.; Davis, R.J. The role of JNK in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 634–645.

- Fuertes, M.B.; Woo, S.-R.; Burnett, B.; Fu, Y.-X.; Gajewski, T.F. Type I interferon response and innate immune sensing of cancer. Trends Immunol. 2012, 34, 67–73.

- Aroucha, D.; Carmo, R.D.; Moura, P.; Silva, J.; Vasconcelos, L.; Cavalcanti, M.; Muniz, M.T.C.; Aroucha, M.; Siqueira, E.; Cahú, G.; et al. High tumor necrosis factor-α/interleukin-10 ratio is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Cytokine 2013, 62, 421–425.

- Haybaeck, J.; Zeller, N.; Wolf, M.J.; Weber, A.; Wagner, U.; Kurrer, M.O.; Bremer, J.; Iezzi, G.; Graf, R.; Clavien, P.-A.; et al. A Lymphotoxin-Driven Pathway to Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 295–308.

- Ramzan, M.; Sturm, N.; Decaens, T.; Bioulac-Sage, P.; Bancel, B.; Merle, P.; Tran Van Nhieu, J.; Slama, R.; Letoublon, C.; Zarski, J.P. Liver-infiltrating CD 8+ lymphocytes as prognostic factor for tumour recurrence in hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2016, 36, 434–444.

- Piconese, S.; Timperi, E.; Pacella, I.; Schinzari, V.; Tripodo, C.; Rossi, M.; Guglielmo, N.; Mennini, G.; Grazi, G.L.; Di Filippo, S.; et al. Human OX40 tunes the function of regulatory T cells in tumor and nontumor areas of hepatitis C virus-infected liver tissue. Hepatology 2014, 60, 1494–1507.

- Lu, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhan, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Sun, S.; Guo, X.; Yin, H.; Wei, Y.; Li, S.; et al. Targeting Tumor-Associated Antigens in Hepatocellular Carcinoma for Immunotherapy: Past Pitfalls and Future Strategies. Hepatology 2020, 73, 821–832.

- Flecken, T.; Schmidt, N.; Hild, S.; Gostick, E.; Drognitz, O.; Zeiser, R.; Schemmer, P.; Bruns, H.; Eiermann, T.; Price, D.A.; et al. Immunodominance and functional alterations of tumor-associated antigen-specific CD8 + T-cell responses in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013, 59, 1415–1426.

- Blank, C.U.; Haining, W.N.; Held, W.; Hogan, P.G.; Kallies, A.; Lugli, E.; Lynn, R.C.; Philip, M.; Rao, A.; Restifo, N.P.; et al. Defining ‘T cell exhaustion’. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 665–674.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!