Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Engineering, Chemical

Several obstacles remain in the way of widespread hydrogen use, most of which are related to transport and storage. Dilute formic acid (FA) is recognized asa a safe fuel for low-temperature fuel cells. FA is examined as a potential hydrogen storage molecule that can be dehydrogenated to yield highly pure hydrogen (H2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) with very little carbon monoxide (CO) gas produced via nanoheterogeneous catalysts.

- nanoheterogeneous catalysts

- formic acid (FA)

- dehydrogenation

- chemical hydrogen storage

- hydrogen economy

- sustainable energy

1. Introduction

Transportation and other energy-related sectors will be highly needed as safe and sustainable energy carriers in the future. Researchers are working in various sectors such as geothermal power, lithium-ion batteries, solar energy conversion, and nuclear energy, all of which have the potential to solve the energy crisis in the foreseeable future [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. Hydrogen (H2) is a viable medium-term energy storage option. It is expected to contribute significantly to the future energy system as a supplementary fuel and energy carrier [8][9][10]. Hydrogen has a high specific energy of 33.30 kWh kg−1 than diesel, which holds only about 12–14 kWh kg−1. On the other hand, a hydrogen economy is unlikely to emerge unless major integrated technological advancements in H2 generation, storage, and delivery systems are achieved [11]. Figure 1 summarizes the key advantages of hydrogen gas as an energy carrier [8][12].

Figure 1. Advantages of hydrogen energy.

Creating a safe and effective hydrogen storage system is a major problem [13][14]. Accordingly, various sophisticated research techniques to create novel materials that store and distribute hydrogen at satisfactory rates have been developed to utilize hydrogen as a green energy source and solve the challenges of its efficient and safe storage. Physical or chemical storage can be classified according to the methods used. In the physical storage technique, H2 can be held in its diatomic molecule state in a covered vessel under low temperatures and high pressure, such as in the case of cryo-compression and tanks of high pressure [15], or adsorbed on high surface area materials, such as metal-organic frameworks [3][16][17][18][19], clathrate hydrates [20], zeolites [21][22] and various carbon materials [23][24][25][26]. In the chemical storage technique, H2 is stored in a chemically bonded state rather than in a molecular state. Typically, certain appropriate compounds have been selected because they have greater hydrogen content and can release hydrogen effectively at ambient conditions (temperature and pressure) by catalytic or non-catalytic methods. Examples of such compounds include hydrous hydrazine, metal amidoborates, metal borohydrides, ammonia borane, sodium borohydride and formic acid (HCOOH; FA) [27][28][29][30][31]. However, because of their poor kinetics for reversible hydrogen adsorption-desorption interactions, low intrinsic thermal conductivity, thermodynamic stability, toxicity, and high price, the practical applicability of several of these hydrogen storage compounds is greatly limited [32].

Organic liquid molecules such as formic acid (FA) have attracted interest because of their high energy density, low toxicity, and ease of handling [33][34]. Formic acid is one of the primary products generated during biomass processing, containing 4.4 wt.% hydrogen. In addition, pure FA contains 52 g H2/L or 43.8 g H2/kg, which makes it one of the important liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHC) [35]. Furthermore, FA transportation and refilling are simple because FA is liquid at room temperature; this allows it to be handled similarly to diesel and gasoline [36].

Formic acid is a highly promising hydrogen storage substance available nowadays. It outperforms most other state-of-the-art hydrogen storage materials in terms of usable/net capacity. In addition to its advantages, FA is highly stable at ambient temperature without catalysts. Besides its inherent properties, another significant advantage of using FA as a hydrogen storage substance is that even the carbon dioxide (CO2) produced during FA dehydrogenation can be hydrogenated later; this regenerates FA molecules in a carbon-free release process. Moreover, FA can serve as a connection between renewable energy and hydrogen fuel cells. Progress can only be achieved with the right catalysts.

Other liquid organic compounds, commonly known as liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHC) [37], such as methanol carbazole, cycloalkanes, and others, have been intensively explored in addition to formic acid. However, these compounds have several drawbacks that make them unsuitable as hydrogen storage materials, including toxicity, expense, poor stability, slow dehydrogenation kinetics, and low regeneration efficiency [38][39].

2. Formic Acid Decomposition

Fuel cells have remained unpopular because of the high cost of creating, storing, and transporting hydrogen. Rather than delivering hydrogen gas, having a chemical hydrogen storage substance or hydrogen-containing substance which can be decomposed under ambient circumstances to create H2 gas whenever needed is more practical.

Using a catalytic dehydrogenation process can release the hydrogen contained in FA through two main pathways (i) dehydrogenation/decarboxylation yielding H2 and CO2, and (ii) dehydration/decarboxylation yielding H2O and CO (Equations (1) and (2)) [40][41][42].

The CO-free degradation of formic acid in the pathway (i) is essential for formic acid-based hydrogen storage, whereas pathway (ii) produces CO, which is an undesirable product that deactivates fuel cell catalysts. Therefore, pathway (ii) should be avoided. Based on this, and depending on the catalysts, reaction temperatures and pH values of the solutions, carbon monoxide (CO), a deadly poison to fuel cell catalysts, can also be produced by an undesired dehydration pathway (Equation (2)). High temperatures generally enhance dehydration during the reaction [43][44]. Fuel cell systems require ultrapure hydrogen to generate energy, and because CO poisons them, intake CO concentrations should be kept below 20 ppm to avoid long-term performance loss.

The dehydrogenation of FA (Equation (1)) produces only gaseous products (H2/CO2), with no accumulation or formation of by-products, making it advantageous compared to other alternative hydrogen carriers, particularly for portable usage. The gas combination produced is used as a feed-gas for an H2/air fuel cell directly [45]. Because such fuel cells are intended to deliver energy to portable devices with limited heat management capabilities, mild temperatures are crucial.

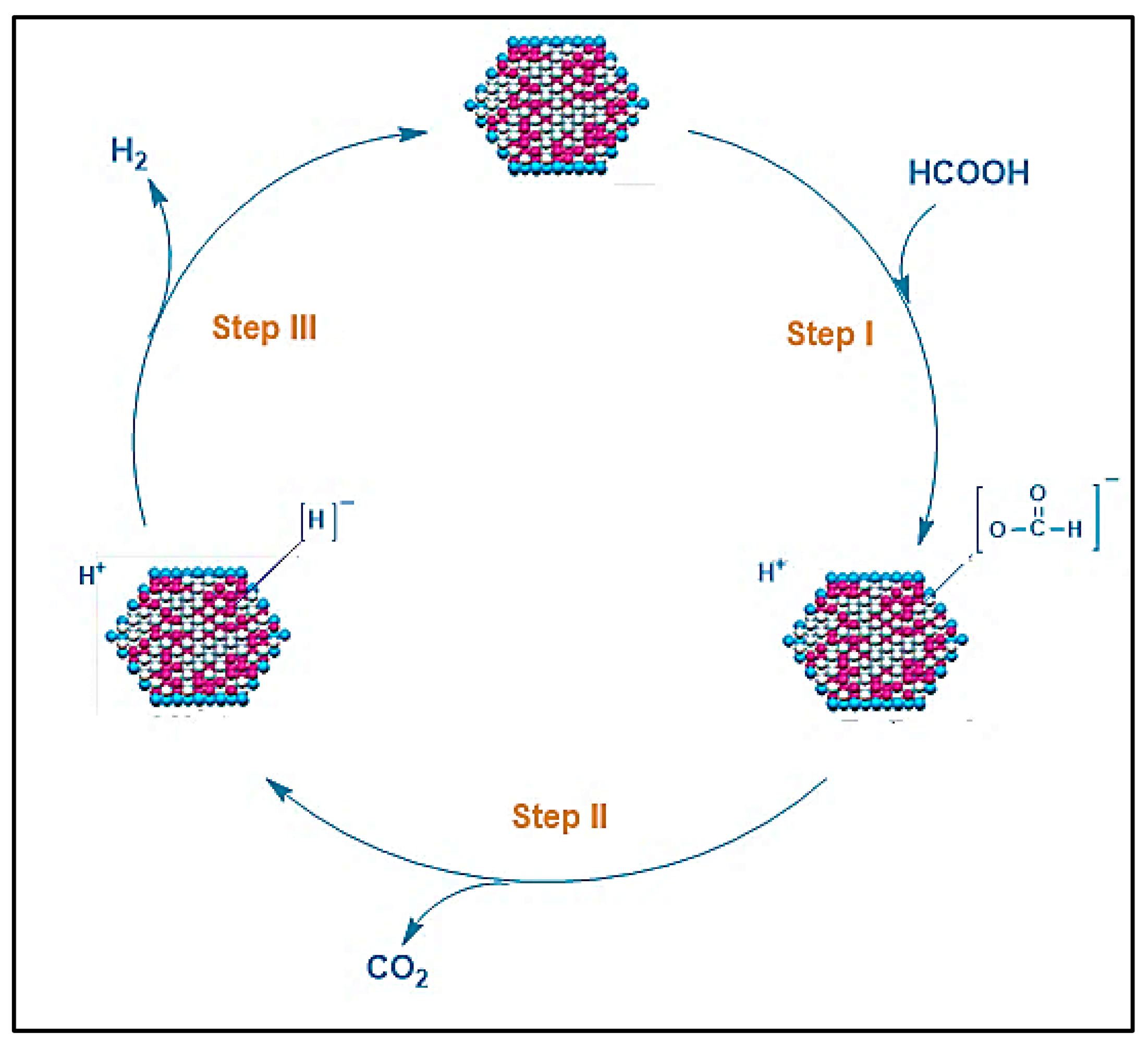

Figure 2 presents a plausible mechanism for producing hydrogen from formic acid using metal nanoparticle (MN) catalysts. The following reactions would occur as a result of the mechanism:

Figure 2. Reaction mechanism described for H2 generation from FA dehydrogenation catalyzed by metal nanoparticle catalysts.

3. Heterogeneous Catalysts

Studying FA decomposition using heterogeneous catalysts has occurred since the 1930s, yet optimizing the catalysts, and measuring the CO produced by the FA dehydration-side reaction were not fully examined in early research [46]. In that state, the reaction was mostly examined in the gas phase, necessitating temperatures greater than 100 °C (formic acid’s usual boiling point) or using an inert carrier gas that dilutes FA under its saturated vapor pressure; both would add to the setup’s complexity. Because of their large surface area/mass ratio, nanoparticles are particularly well suited to act as catalysts in fuel cells. As a result, their utilization saves time and money. Developing heterogeneous catalysts for liquid-phase FA dehydrogenation is therefore crucially required [47]. A number of publications on nanoheterogeneous catalysts with different support materials for the dehydrogenation of aqueous FA have been published, emphasizing H2 selectivity and low-temperature activity.

3.1. Monometallic Heterogeneous Catalyst

Several studies have been published recently on monometallic noble metal nanoparticles (NPs) based on different catalysts for FA dehydrogenation in an aqueous medium [48][49][50][51]. Bi et al. [52] used hyper-dispersed subnanometric gold NPs on ZrO2 as catalysts to show the moderate and selective dehydrogenation of an FA/amine mixture. Under ambient conditions, the catalytic processes happen effectively and selectively (100%), with high TOFs/catalyst turnover numbers (TONs), and without generating any undesirable by-products such as CO. At ambient temperature, very efficient hydrogen was obtained from the production, from aqueous solution, of formic acid/sodium formate catalyzed via in situ-produced Pd/C with citric acid. Surprisingly, the addition of citric acid in the middle of the synthesis and development of Pd NPs on carbon improves the catalytically activity of the resultant Pd/C, on which the greatest conversion and turnover frequency for the breakdown of formic acid/sodium formate system can be achieved at ambient temperature [53].

3.2. Bimetallic Heterogeneous Catalyst

It is generally known that adding a secondary metal to the active phase can change the electrical characteristics and adsorption behavior and the metal dispersion/particle size. Presently, supported Pd-based nanocatalysts are shown to be active for the dehydrogenation of aqueous FA [48][54][55][56][53]. Adding Au or Ag to Pd NPs in an aqueous medium significantly enhances their stability and catalytic activity [35][57][58][59][60]. The enhanced catalytic activity of bimetallic Pd-Au/C and Pd-Ag/C catalysts was attributable to the greater tolerance to CO poisoning of Ag and Au. The addition of CeO2(H2O)x increased catalytic activity even more because CeO2 forms cationic palladium species with strong activity in CO oxidation [61] and methanol decomposition [62]. An alternative justification is that CeO2(H2O)x on the Pd surface can trigger FA breakdown via a more effective mechanism, resulting in less poisoning intermediates [63].

3.3. Trimetallic Heterogeneous Catalyst

Trimetallic NPs have lately acquired increased attention, particularly in catalytic systems, because of their novel physicochemical features (e.g., catalytic, electrical, optical, and magnetic) which are caused by their monometallic counterparts’ synergistic effects [64]. Yurderi et al. used a simple and repeatable wet impregnation followed by a simultaneous reduction method at room temperature to synthesize Pd-Ni-Ag (trimetallic nanoparticles) with various metal ratios, as well as their Pd-Ni, Ni-Ag, and Pd-Ag (bimetallic) and Pd, Ni, and Ag (monometallic) counterparts, loaded on active carbon [65]. Under mild reaction conditions, all composites produced were used as nanoheterogeneous catalysts to break down FA.

4. Formic Acid Fuel Cells (DFAFCs)

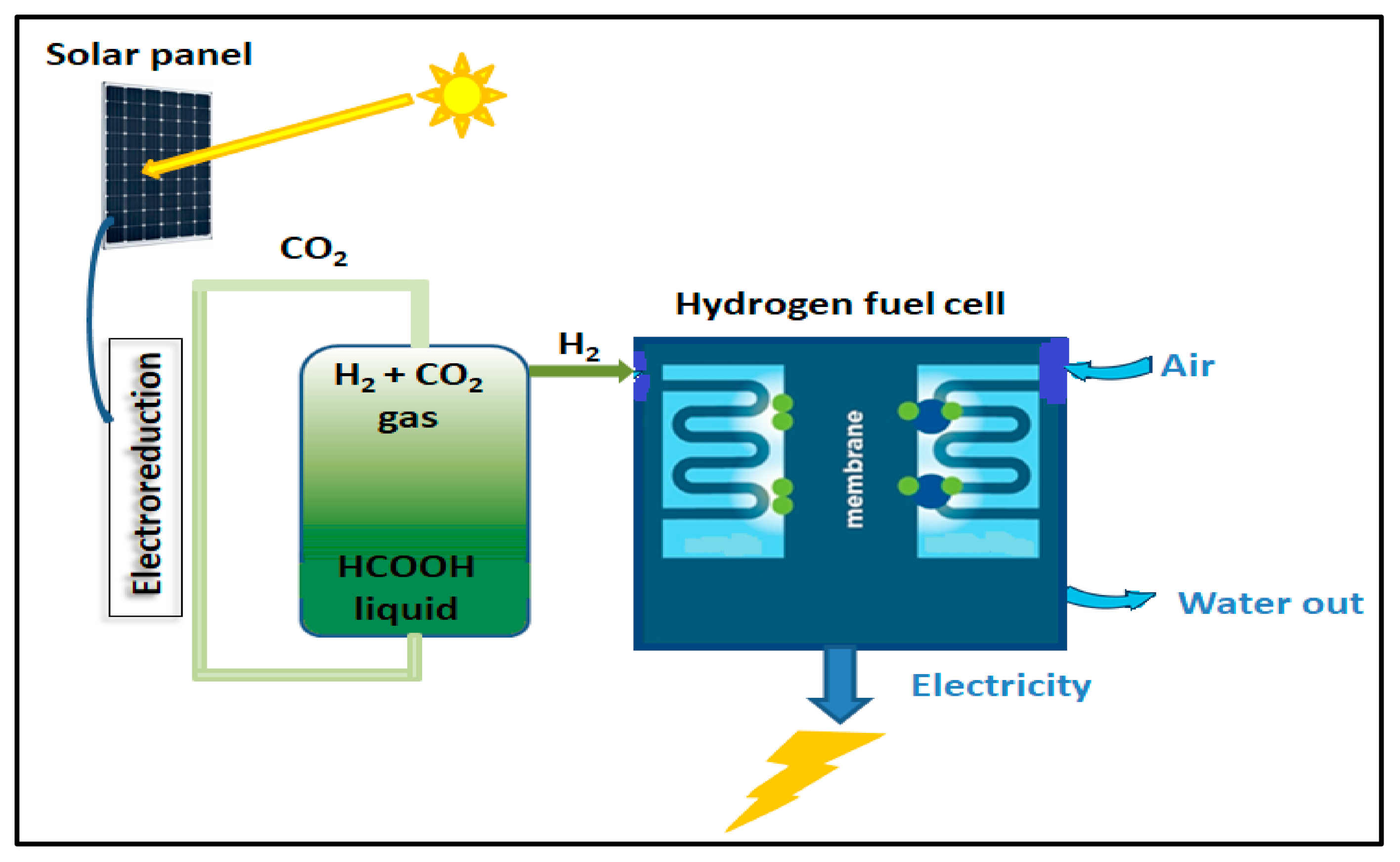

FA’s hyper-gravimetric capability was recognized, and using FA as a secondary fuel in direct FA fuel cells (DFAFCs) was suggested and investigated [66]. While DFAFCs suffer from significant problems, hydrogen fuel cells perform a role in a well-established technology that has been commercialized in fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) with outputs of over 140 kW and ranges of over 600 km. As a result, producing H2 selectively from FA to power hydrogen fuel cells is a potential strategy with a speedy time-to-market. As a traditional fuel, energy discharge includes FA consumption, resulting in a massive release of CO2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Basics of formic acid fuel cell and hydrogen energy.

Direct formic acid fuel cells work in the same way as other fuel cells. They create electricity by oxidizing FA and reducing O2. FA and O2 (or air) are supplied to the anode and cathode, respectively, in the electrochemical cell. Protons can pass across an electrolyte membrane [67].

5. Formic Acid Production

Formic acid is a crucial component created from a variety of chemical molecules. FA is found in the venom of ants in nature [68] and is emitted into the atmosphere as a result of forest emissions. Various chemical techniques can be used to prepare it. The most frequent industrial procedure is the synthesis of methyl formate from a mixture of carbon monoxide and methanol in the existence of a strong base at 80 °C and 40 atm, followed by hydrolysis of the methyl formate to yield FA [69]. FA can also be synthesized as a by-product of acetic acid production, biomass oxidation, CO2 hydrogenation and biosynthesis via carbon dioxide reduction mediated by the enzyme formate dehydrogenase [70][71]. Despite the enormous progress that has been made in nano-chemistry and nanotechnology over the last two decades, and that forming FA from carbonates (primarily Pd-based) has been a subject of research for some time, few instances of supported metal catalysts at the nanometer scale for direct hydrogenation of carbon dioxide have been reported. These primarily involve Au, Pd, and Ru.

6. Conclusions

The benefits of a hydrogen economy are obvious, even if significant research is required to accomplish the essential technological advancements. Formic acid is an environmentally-benign hydrogen storage substance because of its easy storage and lack of poisonousness. Its production through dehydrogenation releases only gaseous products (H2/CO2). Interestingly, CO2 can be converted back to formic acid using catalysts under moderate conditions, resulting in a CO2-neutral hydrogen storage cycle. Noble metals, such as Au and Pd, can serve as nanoheterogeneous catalysts that work in aqueous formic acid solutions and ambient temperature (20–50 °C). The Pd nanoparticles are employed in most nanoheterogeneous catalysts used in the formic acid dehydrogenation process. However, chemical intermediates adsorb on the nanoparticle surfaces and deactivate Pd monometallic systems. The situation with heterogeneous formic acid decomposition catalysts is identical to that with homogeneous systems. While the activity and H2 selectivity have not yet been achieved homogeneous system levels and most heterogeneous systems tested still have some degree of decarbonylation activity, this gap is narrowing. The recent use of state-of-the-art nanoparticle synthesis techniques has resulted in a variety of high-performance catalysts, including bimetallic and trimetallic Pd and Au combinations that produce high-quality H2 with minimal CO concentration. The direct formic acid fuel cell (DFAFC) example marks significant progress toward prototype development, scale-up, and commercialization. Furthermore, CO2 may be converted back to formic acid using catalysts under moderate conditions, resulting in a CO2-neutral hydrogen storage cycle.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/catal12030324

References

- Durmaz, T. The economics of CCS: Why have CCS technologies not had an international breakthrough? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 95, 328–340.

- Nguyen, K.H.; Kakinaka, M. Renewable energy consumption, carbon emissions, and development stages: Some evidence from panel cointegration analysis. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1049–1057.

- Li, S.-L.; Xu, Q. Metal–organic frameworks as platforms for clean energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1656–1683.

- Onishi, N.; Iguchi, M.; Yang, X.; Kanega, R.; Kawanami, H.; Xu, Q.; Himeda, Y. Development of effective catalysts for hydrogen storage technology using formic acid. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1801275.

- Li, X.; Yang, X.; Xue, H.; Pang, H.; Xu, Q. Metal–organic frameworks as a platform for clean energy applications. EnergyChem 2020, 2, 100027.

- Lang, C.; Jia, Y.; Yao, X. Recent advances in liquid-phase chemical hydrogen storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 26, 290–312.

- Stucchi, M.; Capelli, S.; Cardaci, S.; Cattaneo, S.; Jouve, A.; Beck, A.; Sáfrán, G.; Evangelisti, C.; Villa, A.; Prati, L. Synergistic Effect in Au-Cu Bimetallic Catalysts for the Valorization of Lignin-Derived Compounds. Catalysts 2020, 10, 332.

- Rosen, M.A.; Koohi-Fayegh, S. The prospects for hydrogen as an energy carrier: An overview of hydrogen energy and hydrogen energy systems. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2016, 1, 10–29.

- De Blasio, N.; Pflugmann, F.; Lee, H.; Hua, C.; Nuñez-Jimenez, A.; Fallon, P. Mission Hydrogen: Accelerating the Transition to a Low Carbon Economy. October 2021. Available online: https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/mission-hydrogen-accelerating-transition-low-carbon-economy (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Van Renssen, S. The hydrogen solution? Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 799–801.

- Navlani-García, M.; Mori, K.; Kuwahara, Y.; Yamashita, H. Recent strategies targeting efficient hydrogen production from chemical hydrogen storage materials over carbon-supported catalysts. NPG Asia Mater. 2018, 10, 277–292.

- Hafeez, S.; Barlocco, I.; Al-Salem, S.M.; Villa, A.; Chen, X.; Delgado, J.J.; Manos, G.; Dimitratos, N.; Constantinou, A. Experimental and Process Modelling Investigation of the Hydrogen Generation from Formic Acid Decomposition Using a Pd/Zn Catalyst. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8462.

- Nie, W.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Feng, G.; Yao, Q.; Lu, Z.-H. An amine-functionalized mesoporous silica-supported PdIr catalyst: Boosting room-temperature hydrogen generation from formic acid. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 709–717.

- Wen, C.; Rogie, B.; Kærn, M.R.; Rothuizen, E.D. A first study of the potential of integrating an ejector in hydrogen fuelling stations for fuelling high pressure hydrogen vehicles. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 113958.

- Xiao, R.; Tian, G.; Hou, Y.; Chen, S.; Cheng, C.; Chen, L. Effects of cooling-recovery venting on the performance of cryo-compressed hydrogen storage for automotive applications. Appl. Energy 2020, 269, 115143.

- Chen, Y.; Li, P.; Noh, H.; Kung, C.; Buru, C.T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Farha, O.K. Stabilization of Formate Dehydrogenase in a Metal–Organic Framework for Bioelectrocatalytic Reduction of CO 2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 7682–7686.

- Giappa, R.M.; Tylianakis, E.; Di Gennaro, M.; Gkagkas, K.; Froudakis, G.E. A combination of multi-scale calculations with machine learning for investigating hydrogen storage in metal organic frameworks. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 27612–27621.

- Barnett, B.R.; Evans, H.A.; Su, G.M.; Jiang, H.Z.H.; Chakraborty, R.; Banyeretse, D.; Hartman, T.J.; Martinez, M.B.; Trump, B.A.; Tarver, J.D.; et al. Observation of an Intermediate to H2 Binding in a Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14884–14894.

- Kalasha, K.R.; Albayatib, T.M. Remediation of oil refinery wastewater implementing functionalized mesoporous materials MCM-41 in batch and continuous adsorption process. Desalin Water Treat 2021, 220, 130–141.

- Gupta, A.; Baron, G.V.; Perreault, P.; Lenaerts, S.; Ciocarlan, R.-G.; Cool, P.; Mileo, P.G.; Rogge, S.; Van Speybroeck, V.; Watson, G.; et al. Hydrogen Clathrates: Next Generation Hydrogen Storage Materials. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 41, 69–107.

- Farajzadeh, M.; Alamgholiloo, H.; Nasibipour, F.; Banaei, R.; Rostamnia, S. Anchoring Pd-nanoparticles on dithiocarbamate- functionalized SBA-15 for hydrogen generation from formic acid. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9.

- Alardhi, S.M.; Alrubaye, J.M.; Albayati, T.M. Adsorption of Methyl Green dye onto MCM-41: Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic studies. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 179, 323–331.

- Zhang, X.; Shang, N.; Shang, H.; Du, T.; Zhou, X.; Feng, C.; Gao, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z. Nitrogen-Decorated Porous Carbon Supported AgPd Nanoparticles for Boosting Hydrogen Generation from Formic Acid. Energy Technol. 2019, 7, 140–145.

- Mohan, M.; Sharma, V.K.; Kumar, E.A.; Gayathri, V. Hydrogen storage in carbon materials—A review. Energy Storage 2019, 1, e35.

- Nechaev, Y.S.; Denisov, E.A.; Cheretaeva, A.O.; Davydov, S.Y.; Öchsner, A. On the real possibility of “super” hydrogen intercalation into graphite nanofibers. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2022, 30, 211–219.

- Wang, C.; Kim, J.; Tang, J.; Kim, M.; Lim, H.; Malgras, V.; You, J.; Xu, Q.; Li, J.; Yamauchi, Y. New Strategies for Novel MOF-Derived Carbon Materials Based on Nanoarchitectures. Chem 2020, 6, 19–40.

- Zheng, J.; Wang, C.-G.; Zhou, H.; Ye, E.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Loh, X.J. Current Research Trends and Perspectives on Solid-State Nanomaterials in Hydrogen Storage. Research 2021, 2021, 1–39.

- Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, J.-W.; Lee, K.-J.; Park, S.-J. Recent Progress Using Solid-State Materials for Hydrogen Storage: A Short Review. Processes 2022, 10, 304.

- Chen, Z.; Kirlikovali, K.O.; Idrees, K.B.; Wasson, M.C.; Farha, O.K. Porous materials for hydrogen storage. Chem 2022.

- Cai, X.-H.; Xie, B. Formic Acid as an Inexpensive and Convenient Reagent. Curr. Org. Chem. 2021, 25, 223–247.

- Nazemi, A.; Steeves, A.; Kulik, H. Influence of the Greater Protein Environment on the Electrostatic Potential in Metalloenzyme Active Sites: The Case of Formate Dehydrogenase. chemRxiv 2021.

- Zhong, H.; Iguchi, M.; Chatterjee, M.; Himeda, Y.; Xu, Q.; Kawanami, H. Formic Acid-Based Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier System with Heterogeneous Catalysts. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2018, 2, 1700161.

- Rodriguez-Lugo, R.E.; Trincado, M.; Vogt, M.; Tewes, F.; Santiso-Quinones, G.; Grützmacher, H. A homogeneous transition metal complex for clean hydrogen production from methanol–water mixtures. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 342–347.

- Song, F.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Diamine-Alkalized Reduced Graphene Oxide: Immobilization of Sub-2 nm Palladium Nanoparticles and Optimization of Catalytic Activity for Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5141–5144.

- Ping, Y.; Yan, J.M.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, H.L.; Jiang, Q. Ag 0.1-Pd 0.9/rGO: An efficient catalyst for hydrogen generation from formic acid/sodium formate. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 12188–12191.

- Enthaler, S.; von Langermann, J.; Schmidt, T. Carbon dioxide and formic acid—The couple for environmental-friendly hydrogen storage? Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 1207–1217.

- Teichmann, D.; Arlt, W.; Wasserscheid, P. Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers as an efficient vector for the transport and storage of renewable energy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 18118–18132.

- Nielsen, M.; Alberico, E.; Baumann, W.; Drexler, H.-J.; Junge, H.; Gladiali, S.; Beller, M. Low-temperature aqueous-phase methanol dehydrogenation to hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Nature 2013, 495, 85–89.

- Monney, A.; Barsch, E.; Sponholz, P.; Junge, H.; Ludwig, R.; Beller, M. Base-free hydrogen generation from methanol using a bi-catalytic system. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 707–709.

- Loges, B.; Boddien, A.; Gärtner, F.; Junge, H.; Beller, M. Catalytic Generation of Hydrogen from Formic acid and its Derivatives: Useful Hydrogen Storage Materials. Top. Catal. 2010, 53, 902–914.

- Hull, J.F.; Himeda, Y.; Wang, W.-H.; Hashiguchi, B.G.; A Periana, R.; Szalda, D.J.; Muckerman, J.T.; Fujita, E. Reversible hydrogen storage using CO2 and a proton-switchable iridium catalyst in aqueous media under mild temperatures and pressures. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 383–388.

- Loges, B.; Boddien, A.; Junge, H.; Beller, M. Controlled generation of hydrogen from formic acid amine adducts at room temperature and application in H2/O2 fuel cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3962–3965.

- Joó, F. Breakthroughs in Hydrogen Storage-Formic Acid as a Sustainable Storage Material for Hydrogen. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 805–808.

- Makowski, P.; Thomas, A.; Kuhn, P.; Goettmann, F. Organic materials for hydrogen storage applications: From physisorption on organic solids to chemisorption in organic molecules. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 480–490.

- Mardini, N.; Bicer, Y. Direct synthesis of formic acid as hydrogen carrier from CO2 for cleaner power generation through direct formic acid fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 13050–13060.

- Grasemann, M.; Laurenczy, G. Formic acid as a hydrogen source—Recent developments and future trends. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8171–8181.

- Zhu, Q.-L.; Xu, Q. Liquid organic and inorganic chemical hydrides for high-capacity hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 478–512.

- Zhu, Q.-L.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Sodium hydroxide-assisted growth of uniform Pd nanoparticles on nanoporous carbon MSC-30 for efficient and complete dehydrogenation of formic acid under ambient conditions. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 195–199.

- Akbayrak, S.; Tonbul, Y.; Özkar, S. Nanoceria supported palladium(0) nanoparticles: Superb catalyst in dehydrogenation of formic acid at room temperature. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 206, 384–392.

- Ojeda, M.; Iglesia, E. Formic Acid Dehydrogenation on Au-Based Catalysts at Near-Ambient Temperatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4800–4803.

- Liu, J.; Lan, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Wu, X. Facile synthesis of agglomerated Ag–Pd bimetallic dendrites with performance for hydrogen generation from formic acid. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 6395–6403.

- Bi, Q.-Y.; Du, X.-L.; Liu, Y.-M.; Cao, Y.; He, H.-Y.; Fan, K.-N. Efficient Subnanometric Gold-Catalyzed Hydrogen Generation via Formic Acid Decomposition under Ambient Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8926–8933.

- Wang, Z.-L.; Yan, J.-M.; Wang, H.-L.; Ping, Y.; Jiang, Q. Pd/C Synthesized with Citric Acid: An Efficient Catalyst for Hydrogen Generation from Formic Acid/Sodium Formate. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 598.

- Jiang, K.; Xu, K.; Zou, S.; Cai, W.-B. B-Doped Pd Catalyst: Boosting Room-Temperature Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid–Formate Solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4861–4864.

- Lee, J.H.; Ryu, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Nam, S.-W.; Han, J.H.; Lim, T.-H.; Gautam, S.; Chae, K.H.; Yoon, C.W. Carbon dioxide mediated, reversible chemical hydrogen storage using a Pd nanocatalyst supported on mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 9490–9495.

- Sanchez, F.; Alotaibi, M.H.; Motta, D.; Chan-Thaw, C.E.; Rakotomahevitra, A.; Tabanelli, T.; Roldan, A.; Hammond, C.; He, Q.; Davies, T.; et al. Hydrogen production from formic acid decomposition in the liquid phase using Pd nanoparticles supported on CNFs with different surface properties. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2018, 2, 2705–2716.

- Tedsree, K.; Li, T.; Jones, S.C.; Chan, C.W.A.; Yu, K.M.K.; Bagot, P.; Marquis, E.; Smith, G.D.W.; Tsang, S.C.E. Hydrogen production from formic acid decomposition at room temperature using a Ag–Pd core–shell nanocatalyst. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 302–307.

- Wang, Z.-L.; Yan, J.-M.; Wang, H.-L.; Ping, Y.; Jiang, Q. core–shell nanoclusters growing on nitrogen-doped mildly reduced graphene oxide with enhanced catalytic performance for hydrogen generation from formic acid. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 12721–12725.

- Zhang, S.; Metin, Ö.; Su, D.; Sun, S. Monodisperse AgPd Alloy Nanoparticles and Their Superior Catalysis for the Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3681–3684.

- Metin, Ö.; Sun, X.; Sun, S. Monodisperse gold–palladium alloy nanoparticles and their composition-controlled catalysis in formic acid dehydrogenation under mild conditions. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 910–912.

- Glaspell, G.; Fuoco, A.L.; El-Shall, M.S. Microwave Synthesis of Supported Au and Pd Nanoparticle Catalysts for CO Oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 17350–17355.

- Shen, W.-J.; Matsumura, Y. Interaction between palladium and the support in Pd/CeO2 prepared by deposition–precipitation method and the catalytic activity for methanol decomposition. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2000, 153, 165–168.

- Zhou, X.; Huang, Y.; Xing, W.; Liu, C.; Liao, J.; Lu, T. High-quality hydrogen from the catalyzed decomposition of formic acid by Pd–Au/C and Pd–Ag/C. Chem. Commun. 2008, 2008, 3540–3542.

- Park, J.H.; Ahn, H.S. Electrochemical synthesis of multimetallic nanoparticles and their application in alkaline oxygen reduction catalysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 504, 144517.

- Yurderi, M.; Bulut, A.; Zahmakiran, M.; Kaya, M. Carbon supported trimetallic PdNiAg nanoparticles as highly active, selective and reusable catalyst in the formic acid decomposition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 160–161, 514–524.

- Yang, S.; Chung, Y.; Lee, K.-S.; Kwon, Y. Enhancements in catalytic activity and duration of PdFe bimetallic catalysts and their use in direct formic acid fuel cells. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 90, 351–357.

- Maslan, H.N.; Rosli, M.I.; Masdar, M.S. Three-dimensional CFD modeling of a direct formic acid fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 30627–30635.

- Yu, X.; Pickup, P.G. Recent advances in direct formic acid fuel cells (DFAFC). J. Power Sources 2008, 182, 124–132.

- Reutemann, W.; Kieczka, H. Formic acid. Ullmann’s Encycl. Ind. Chem. 2016, 1, 1–22.

- Miyatani, R.; Amao, Y. Bio-CO2 fixation with formate dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and water-soluble zinc porphyrin by visible light. Biotechnol. Lett. 2002, 24, 1931–1934.

- Miyatani, R.; Amao, Y. Photochemical synthesis of formic acid from CO2 with formate dehydrogenase and water-soluble zinc porphyrin. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2004, 27, 121–125.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!