2. Development, Regulation and Heterogeneity of cDC1

Ontogeny studies on murine models are beginning to unravel the development of DC subsets; however, the translation of these discoveries to human biology is not always straightforward [

46]. Human DCs develop from multipotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) primed by predestined-related but distinct pathways of lympho-myeloid hematopoiesis, which share a common transitory phenotype and differentiate into specific subsets by the influence of lineage-specific transcription factors, particularly IRF8 and IRF4 [

45,

54]. Contemporary models of lympho-myeloid hematopoiesis place the lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (LMPP) at the apex of all myeloid and lymphoid lineages, separated from megakaryocyte and erythroid potential (MkE) [

45]. Located in the bone marrow, this precursor differentiates into the granulocyte macrophage DC progenitor (GMDP), with the potential to generate granulocyte, macrophage and DC populations [

45,

55]. A phenotype shift occurs when these progenitor cells start to express CD115 (M-CSFR), giving rise to macrophage DC progenitors (MDPs). Subsequently, MDPs increase the expression of CD123 and differentiate into CDPs (common DC progenitors) with the capacity to exclusively generate all three DC subsets [

45,

55,

56]. Whereas pDCs terminally differentiate in the bone marrow, DC-restricted precursors not fully expressing the phenotype of differentiated DCs, termed pre-cDCs, migrate through the blood to lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues, where they produce cDC1 and cDC2 (

Figure 1) [

56,

57,

58,

59].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of cDC1 DC development. In the bone marrow, HSC gives rise to the LMPP, which settles at the apex of all myeloid and lymphoid lineages and is separated from the MkE. GMDP derives from the LMPP and produces the MDP (expressing M-CSFR), which further differentiates into the CDP, capable of generating the main DC subsets: pDCs, cDC1 and cDC2. pDCs terminally differentiate in the bone marrow, whereas pre-cDC migrate through the blood to lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues, where they produce cDC1 and cDC2 subsets. Determining the differentiation pathway, Notch-dependent interactions of CDPs with stromal cells, in cooperation with GM-CSF, are crucial for the commitment to the cDC1 lineage, separating their pathway from pDCs. In peripheral tissues, the differentiation into CD141+ cDC1 is controlled by transcription factors, such as IRF8, Batf3 and Id2 (shown in blue). After engagement with the CD141+ pathway, the existence of a two-staged differentiation process of cDC1 populations is proposed, in which XCR1-negative cDC1s under the influence of GM-CSF (shown in red) acquire the expression of XCR1, representing the shift between a pre-cross-presentation phase and a subsequential cross-presenting stage. cDC, conventional dendritic cell; CDP, common DC precursor; DC, dendritic cell; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; GMDP, granulocyte macrophage DC progenitor; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor; M-CSFR, macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor; MDP, macrophage DC precursor; MkE, megakaryocyte and erythroid potential; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell.

cDC1 population development is under the control of a set of key transcription factors, namely IRF8, BATF3, GATA2, PU.1, GFI1 and Id2 [

45,

47,

56,

60,

61]. In accordance, a recent work demonstrated that the concomitant expression of PU.1, IRF8 and BATF3 transcription factors is sufficient for reprogramming both mouse and human fibroblasts so that they acquire a cDC1-like phenotype [

62]. Other in vitro experiments have shown that FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L), GM-CSF, Stem cell factor (SCF), thrombopoietin (TPO), IL-6, IL-3 and IL-4 might play a role in cDC1 differentiation from human CD34

+ progenitors [

46,

56,

63]. Finally, Notch signaling, especially in cooperation with GM-CSF, is crucial for promoting the in vitro differentiation of cDC1 from CD34

+ progenitors [

48]; by blocking the Notch pathway at different time points, it was shown that its signal was particularly important in the beginning of the differentiation process [

48]. These data point out the existence of Notch-dependent lineage bifurcation that separates pDCs and cDC1 pathways from their CDP. Notch-dependent interactions of DC precursors with stromal cells were also proposed to determine the commitment to the cDC1 lineage [

48].

cDC1 are approximately ten times less abundant than cDC2, being present in the blood, lymph nodes, tonsils, spleen, bone marrow and non-lymphoid tissues, such as the skin, lung, intestine and liver [

45,

46,

49]. This DC subset is characterized by a high expression of CD141, low expression of CD11b and CD11c, and the lack of CD14 and SIRPα [

45,

46,

64]. It can also be defined by the intracellular detection of IRF8, without IRF4, which represents the standard for identifying this population [

45,

46]. Based on many comparative studies of human CD141

+ DCs with their murine counterpart CD8

+/CD103

+ DCs, many other markers have been recognized to allow for a more accurate identification of this specific population. The cell surface expression of the C-type-lectin CLEC9A (also known as DNGR-1) and the presence of the adhesion molecule CADM1 (NECL2) and the protein BTLA (CD272) substantially increase the preciseness of the identification [

45,

46,

49,

64]. Among Toll-like receptors (TLRs), cDC1 express TLR3 and TLR9, while lacking TLR4, 5, and 7 [

45,

46,

49,

64]. Additionally, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is also highly expressed in this DC subset [

45,

46]. Between these receptors, human CD141

+ DCs can also be characterized by the expression of the chemokine receptor XCR1 [

45,

46,

47,

64,

65].

Following the commitment to the cDC1 pathway, the heterogeneity of CLEC9A

+ CADM1

+ CD141

+ lineage in the blood was also reported, splitting this population between XCR1

− CXCR4

hi and XCR1

+ DCs [

48]. After in vitro culture of the XCR1

− cells, this DC subset proliferated and acquired XCR1 expression, indicating that these cells are immediate precursors of XCR1

+ cDC1 [

48]. Similarly to mice splenic cDC1, this might indicate the existence of a two-staged differentiation process of human CD141

+ DCs: a pre-cross-presentation phase and a subsequent cross-presenting stage, in which cDC1 acquire the capacity to cross-present antigens due to the GM-CSF-mediated expression of XCR1 (

Figure 1) [

48,

58].

3. The Role of cDC1 in Immunity

In light of the current knowledge on DC immunobiology, cDC1 (CD141

hi CLEC9A

+ XCR1

+) are the most effective human cross-presenting cells and thus potent CTL inducers [

45,

46,

51]. These functional traits are empowered by the expression of molecules such as CLEC9A and XCR1. CLEC9A is a receptor for actin filaments exposed by necrotic cells, allowing their recognition, internalization and routing into the cross-presentation pathway [

45,

46,

66,

67,

68]. In turn, XCR1 is the receptor of the X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (XCL1) and is restrictively expressed by human CD141

+ DCs [

51]. XCL1, also known as lymphotactin, is selectively expressed in NK and CD8

+ T cells at a steady-state, being enhanced during infectious and inflammatory responses [

69]. Therefore, the XCL1-XCR1 axis promotes the physical engagement of NK and CD8

+ T cells with CD141

+XCR1

+ DCs, which amplifies their activation state [

45,

46,

47,

51,

70]. In mice, CD8

+ T lymphocytes abundantly secrete XCL1 after in vivo antigen recognition through CD8

+ DC presentation, increasing the number of antigen-specific CD8

+ T cells and their capacity to secrete IFN-γ. In contrast, the absence of XCL1 was shown to impair cytotoxic responses to antigens cross-presented by CD8

+ DCs [

71]. Finally, the XCL1-XCR1 axis also plays a role in immune homeostasis, specifically in the intestine, where XCL1 produced by activated T cells attracts and enables XCR1

+ DC maturation, which in turn provides support for T cell survival and functioning [

72].

CD141

+ XCR1

+ DCs have been shown to be required for CD8

+ T cell responses upon viral and bacterial infections [

65]. During viral infections, pDCs accumulate at sites of CD8

+ T cell activation, leading to the production of XCL1 by these activated T cells, which in turn attracts CD141

+XCR1

+ DCs. This interaction of pDCs, CD141

+XCR1

+ DCs and CD8

+ T cells leads to optimal signal exchange, where type 1 interferons (IFN1) produced by pDCs improve the maturation and cross-presentation by CD141

+XCR1

+ DCs, thus enhancing the development of the CD8

+ T cell response [

73]. In the case of secondary infections, CD141

+XCR1

+ DCs are needed for the optimum expansion of memory CTLs in response to most pathogens. Moreover, the reactivation of memory CTLs relies on their interactions with CD141+XCR1

+ DCs, an event that is triggered by the DC production of IL-12 and CXCL9 in response to NK cell-derived IFN-γ [

74].

The relevance of cDC1 subsets in tumor immune surveillance has not yet been fully established; however, collected data from experiments with cDC1-deficient animal models, such as

Batf3–/– mice, have revealed that these cells may play a central role [

75]. In fact, the above-mentioned models fail to spontaneously reject tumor grafts and are unable to support adoptive T cell therapies or to adequately respond to an immune checkpoint blockade [

76,

77,

78,

79]. Additionally, studies specifically addressing the nature of DC subsets responsible for cross-presenting peripheral tumor antigens have evidenced migratory XCR1

+ DC as responsible for priming CTL responses [

80,

81].

Although cDC1 are a scarce immune population in the tumor microenvironment, their abundance positively correlates with patient survival across several cancers and is an indicator of the responsiveness to therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors [

77,

78,

79,

82]. A larger number of cDC1 were detected in sentinel lymph nodes of patients with melanoma that received combined low-dose CpG-B and GM-CSF treatment. In vivo and in vitro studies showed that these DCs were derived from blood CD141

+ cDC1 precursors that were recruited to the sentinel lymph nodes by type I IFN and afterward maturated under the combined effect of CpG and GM-CSF. The presence of in vivo CpG/GM-CSF-induced CD141

+DCs in sentinel lymph nodes was correlated with an increased cross-presenting capacity, T cell infiltration and patient survival [

83]. Concordantly, it has been shown that regressing human tumors have higher numbers of intratumoral cDC1, which are necessary for efficient CTL-mediated tumor elimination [

77].

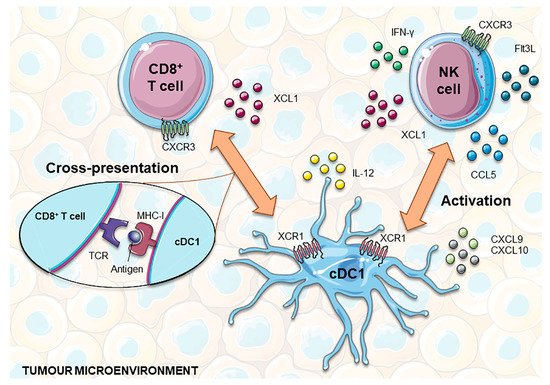

In addition to the cross-presentation of tumor antigens to naïve CD8

+ T cells predominantly occurring in tumor-draining lymph nodes, cDC1 also play an important role in orchestrating local anti-tumor immunity [

84]. In the tumor microenvironment, cDC1s are the main source of CXCL9 and CXCL10 chemokines, which are chemoattractants for CXCR3

+ effector cells, such as T cells, NK cells and innate lymphoid cells (ILC1) (

Figure 2) [

85,

86,

87]. By locally producing high amounts of IL-12, cDC1 help to sustain CTL cytotoxicity and INF-γ production by NK cells [

53,

88]. In turn, IFN-γ enhances IL-12 production by cDC1 and potentiates antigen cross-presentation [

89,

90]. This crosstalk assumes a higher complexity level since NK and CD8

+ T cells produce several factors that promote the recruitment, retention and local expansion of cDC1. In addition to XCL1, NK cells produce CCL5, with mRNA levels of these two chemokines being closely correlated with gene signatures of both NK cells and cDC1 in human biopsies, and associated with overall patient survival [

91,

92]. This suggests that both chemokines may play an important role in attracting cDC1 from blood or surrounding tissues into tumors. Finally, NK cells were recently shown to be one of the major sources of intratumoral Flt3L. This growth factor sustains the viability and functional capacities of cDC1 within the tumor microenvironment and promotes their local differentiation from recruited precursors [

93]. Although most chemokines secreted by tumor cells are chemoattractants of pro-tumorigenic immune cells, such as macrophages and Tregs, in certain circumstances, the production of CCL3, CCL4 and CCL5 mediates the recruitment of cDC1. In accordance with this, the activation of WNT/β-catenin in melanoma cells was shown to result in the ATF3-dependent repression of CCL4 transcription that in turn was correlated with decreased cDC1 numbers at the tumor site [

94].

Figure 2. cDC1 interplay with CD8+ T and NK cells to develop anti-tumor responses. NK and CD8+ T cells express XCL1, which attracts XCR1+ cDC1 into the tumor microenvironment. In addition, NK cells can also produce CCL5, helping to recruit this subset of DCs. In turn, cDC1 are the main source of the chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10, chemoattractants for T and NK cells. Functionally, cDC1 are highly capable of cross-presenting tumor antigens via MHC-I to CD8+ T cells and producing IL-12, which promotes T cell cytotoxicity and the production of INF-γ by NK cells. Furthermore, NK cells produce Flt3L that holds up the viability and functional capacities of cDC1 within the tumor microenvironment and can also promote their local differentiation from recruited precursors. cDC1, classical dendritic cell 1; Flt3L, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; MHC-I, major histocompatibility complex I; NK, natural killer; TCR, T cell receptor; XCL1, X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1.