Electrostatic insect exclusion is a physical approach to pest control in which an apparatus forming an electric field (EF) is applied to capture pests. The EF producer consisted of a negatively charged polyvinyl chloride membrane-insulated iron plate (N-PIP) and a non-insulated grounded iron plate (GIP) paralleled with the N-PIP. An EF was formed in the space between the plates. The magnitude of electric current from the fly was voltage-dependent, and detrimental effects caused by electricity release became more apparent as the applied voltage increased. Bioelectrical measurements showed that electric current caused acute damage and delayed the death of captured flies.

1. Introduction

Electrostatic insect exclusion is a physical pest-control approach in which an apparatus forming an electric field (EF) is applied to capture pests. Previous studies have clarified the insect-capture mechanisms of such tools and evaluated their practicality. Some EF-producing pest-capture systems consist of a negatively charged insulated conductor (metal wire or plate) paralleled with a grounded non-insulated conductor; an EF is generated in the space between them [

1]. Electrostatic insect traps were designed to target small, flying insect pests that can pass through conventional insect-proof nets with mesh sizes of 1–1.5 mm. The first designs consisted of an EF screen comprising a layer of insulated conductor wires arrayed in parallel at definite intervals and a parallel grounded metal net [

4]. This apparatus was installed on lateral greenhouse windows to prevent pest entry [

10,

11]. The EF screen technique has been applied in an electrostatic nursery shelter to protect tomato seedlings from whiteflies, leaf miners, aphids, and thrips in an open-window greenhouse environment [

12], a portable electrostatic insect sweeper to trap whiteflies colonizing host plants [

13], and an electrostatic seedbed cover to capture leaf miners emerging from underground pupae [

14]. In this system, a negative voltage generator picks up negative charge from the ground and supplies it to a linked insulated conductor that accumulates negative charge at its outer surface, dielectrically polarizing the insulator cover to generate the negative charge [

15]. This negative charge positively polarizes a grounded conductor through electrostatic induction [

16]. These opposite charges generates an EF in the space between the opposite poles (i.e., the negatively charged insulated and positively charged grounded conductors).

Charged poles within the EF generate an attractive or repulsive force to other charges in the field [

17]; these forces may be involved in insect capture within the apparatus [

3,

5,

6]. The negatively charged insulated conductor pushes free electrons (negative electricity) out of an insect that enters the EF and sends them to the ground via a grounded conductor; such events are detected as a transient electric current from the insect. It can be hypothesized that the insect is subjected to discharge-mediated positive electrification and then attracted to the negatively charged conductor [

1]. The force generated during this process is sufficiently strong to prevent insects from escaping the trap, making the electrostatic insect trap practically applicable for a wide range of insect pests [

18].

2. EF Production

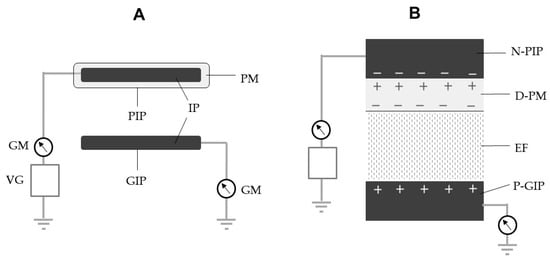

The structure of the EF producer (EFP) is shown in

Figure 2A. Two identical iron plates (2 × 10 cm

2, 2 mm thickness) were used to construct the EFP; one was coated with a soft polyvinyl chloride (PVC) membrane (1 mm thickness; 10

9 Ω cm) (Sonoda Seisakusho, Osaka, Japan) for insulation and linked to a negative voltage generator (Max Electronics, Tokyo, Japan), while the other was non-insulated and linked to a grounded line. The plates were arranged in parallel at a distance of 10 mm. A transformer and Cockcroft circuit [

22] were integrated so as to enhance the initial voltage (12 V) of the voltage generator to achieve the desired voltages (−1 to −20 kV). With this enhanced voltage, the generator is able to pick up negative electricity from the ground and supply it to a PVC-insulated iron plate (PIP) [

23]. Negative electricity accumulates on the surface of the iron plate and polarizes the conductor-side surface (positive) and outer surface of the insulator coating (negative). Eventually, the negative surface charge polarizes the non-insulated grounded iron plate (GIP), so that it is positively charged through electrostatic induction [

16]. The opposite charges on the PIP and GIP generate an EF in the space between them (

Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of (A) an electric field producer (EFP) and (B) dielectric polarization of a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) membrane used to insulate an iron plate, followed by electrostatic induction of a grounded iron plate paralleled with an insulated iron plate. D-PM, dielectrically polarized PVC membrane; EF, electric field; GIP, grounded iron plate; GM, galvanometer; IP, iron plate; N-PIP, negatively charged iron insulated iron plate; P-GIP, positively polarized grounded plate; PIP, PVC-insulated iron plate (charged conductor); PM, PVC membrane coating (insulator); VG, voltage generator.

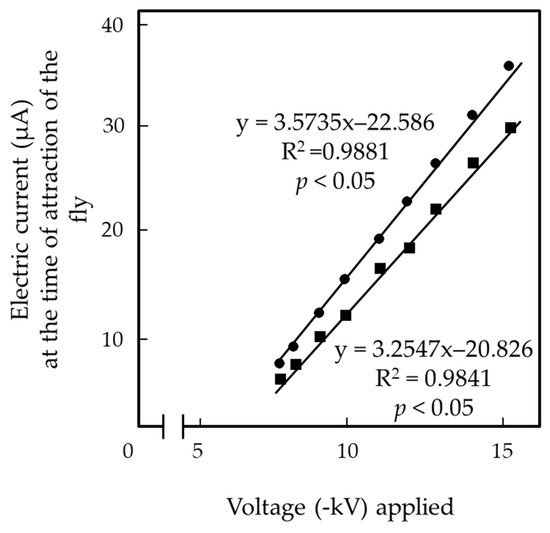

3. Attraction of Houseflies to the N-PIP

One of the most important events for pest control by an EFP is the attraction of the insect to the negatively charged insulated conductor within the EF [

1]. In the present EFP, the attraction of a housefly to the N-PIP was detected in the range from −5.5 to −15 kV. However, at <−7.6 kV, the attracted flies were able to escape from the N-PIP within a short time.

Table 2 lists the time required for houseflies to escape following their attraction to the N-PIP of the negatively charged EFP at different voltages.

Table 2. Time (s) required for male and female adult houseflies captured with the negatively charged PIP of the EFP at different voltages to escape from the PIP.

| Sex |

Age 1 |

Voltage (−kV) Applied to the PIP |

| 5 |

5.5 |

6 |

6.5 |

7 |

7.5 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

15 |

| Male |

7 |

n.a. 2 |

2.6 ± 0.7 a |

4.1 ± 0.3 a |

5.2 ± 0.4 a |

6.9 ± 0.3 a |

7.8 ± 0.6 a |

n.a.e. 3 |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

| 14 |

n.a. |

2.7 ± 0.8 a |

4.2 ± 0.4 a |

5.3 ± 0.5 a |

6.8 ± 0.4 a |

7.7 ± 0.5 a |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

| 21 |

n.a. |

2.4 ± 0.7 a |

4.5 ± 0.5 a |

5.4 ± 0.5 a |

6.9 ± 0.6 a |

7.9 ± 0.6 a |

n.a.e |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

| Female |

7 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

3.1 ± 0.3 b |

3.7 ± 0.5 b |

5.3 ± 0.5 b |

5.9 ± 0.3 b |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

| 14 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

3.2 ± 0.4 b |

3.6 ± 0.5 b |

5.4 ± 0.5 b |

5.9 ± 0.6 b |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

| 21 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

3.3 ± 0.5 b |

3.5 ± 0.5 b |

5.2 ± 0.4 b |

5.9 ± 0.6 b |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

n.a.e. |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/insects13030253