Chronic kidney disease (CKD) afflicts more than 500 million people worldwide and is one of the fastest growing global causes of mortality. When glomerular filtration rate begins to fall, uremic toxins accumulate in the serum and significantly increase the risk of death from cardiovascular disease and other causes. Several of the most harmful uremic toxins are produced by the gut microbiota. Furthermore, many such toxins are protein-bound and are therefore recalcitrant to removal by dialysis. We review the derivation and pathological mechanisms of gut-derived, protein-bound uremic toxins (PBUTs). We further outline the emerging relationship between kidney disease and gut dysbiosis, including the bacterial taxa altered, the regulation of microbial uremic toxin-producing genes, and their downstream physiological and neurological consequences. Finally, we discuss gut-targeted therapeutic strategies employed to reduce PBUTs. We conclude that targeting the gut microbiota is a promising approach for the treatment of CKD by blocking the serum accumulation of PBUTs that cannot be eliminated by dialysis.

- kidney disease, gut dysbiosis, microbiome

- gut-kidney axis,

- intestinal microbiota

1. Introduction

It has been estimated that 500 million people in the world suffer from chronic kidney disease (CKD)[1][2]. The progression of CKD is marked by the gradual loss of the kidneys’ regulatory and filtration capabilities, leaving patients with numerous imbalances and the serum retention of toxic compounds that cause uremic syndrome[3]. The accumulation of uremic toxins has a broad impact on human physiology and is associated with the development of cardiovascular disease, renal fibrosis, neurotoxicity, disrupted hepatic metabolism, and altered bone architecture[4]. Uremic toxins are categorized as (1) small water-soluble molecules, (2) protein-bound compounds, or (3) middle molecules. Although toxins within all three categories have deleterious effects on the body, the most troublesome and hazardous are those that are difficult to remove by dialysis: protein-bound uremic toxins (PBUTs)[5]. Furthermore, many PBUTs derive from the gut as products of the microbial metabolism of dietary compounds[6][7].

Twenty-five gut-derived, protein-bound uremic toxins have been described to date. They can be divided into six primary categories: advanced glycation end-products, hippurates, indoles, phenols, polyamines, and other (Table 1). Protein-bound toxins pose a unique problem in patients suffering from end-stage renal disease (ESRD) as the most effective techniques for removing uremic toxins—dialysis and hemofiltration—are unsuccessful against these molecules. Because PBUTs are not free floating in circulation, only a small fraction of unbound solute is susceptible to the concentration and pressure gradients used to draw waste out of the blood[8]. No therapeutic or other techniques are available to reduce serum levels of gut-derived PBUTs. Therefore, patients have no options to combat uremic syndrome caused by PBUTs, and the subsequent progression from CKD into ESRD.

Table 1. Gut-Derived Protein-Bound Uremic Toxins.

| Gut-Derived PBUT Class | Toxin | Derivation | Pathological Mechanisms |

Associated Comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGEs | 3-Deoxyglucosone Fructoselysine Glyoxal Methylglyoxal N(6)-Carboxymethyllysine Pentosidine |

Diet | ECM crosslink formation Impaired endothelial progenitor cell function NF- kB/MAPK/JNK signaling RAGE signaling |

Arterial stiffness Diabetic nephropathy Endothelial dysfunction Immune system dysregulation |

| Hippurates | Hippuric acid Hydroxyhippuric acid |

Diet | Activation of mitochondrial fission Albumin binding Free radical production NF- kB signaling |

Altered drug pharmacokinetics Endothelial dysfunction Renal tubule damage |

| Indoles | Indole-3-acetic acid Indoxyl glucuronide Indoxyl sulfate Kynurenine Kynurenic acid Melatonin Quinolinic acid |

Microbial metabolism | AhR activation Excessive glutamate release Impaired mitochondrial OXPHOS NF- kB/MAPK signaling NMDA receptor activation Reduced PTH expression |

Bone disease Cardiovascular disease Endothelial dysfunction Inflammation Muscle weakness/atrophy Neurotoxicity Oxidative stress |

| Phenols | Hydroquinone p-cresyl glucuronide p-cresyl sulfate Phenol Phenylacetic acid |

Microbial metabolism | Apoptosis Chromosomal aberrations Inhibition of iNOS expression NADPH oxidase activation ROS production Stimulates Rho-associated protein kinase |

All-cause mortality Cardiovascular disease Inflammation Oxidative stress Renal fibrosis Vascular remodeling |

| Polyamines | Putrescine Spermidine Spermine |

Microbial metabolism/Diet | Inhibition of erythropoietin | Anemia |

| Other | CMPF Homocysteine |

Diet | Albumin binding Altered hepatic metabolism CMPF radical adducts Competitive reabsorption by OAT Degradation of gut epithelial TJ VSMC proliferation |

Altered drug pharmacokinetics Atherosclerosis Increased intestinal permeability Neurological abnormalities Renal tubule damage |

AGE, advanced glycation end product; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; CMPF, 3-carboxy-4-methyl-5-propyl-2-furanpropionic acid; ECM, extracellular matrix; iNOS, nitric oxide synthase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF- kB, nuclear factor kappa B; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; OAT, organic anion transporter; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PBUT, protein-bound uremic toxin; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RAGE, advanced glycan end product-specific receptor; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TJ, tight junctions; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Gut microbial dysbiosis has been implicated in a number of disorders, including CKD, obesity, inflammatory bowel diseases, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease[9]. With respect to CKD, there is a well-established relationship between the decline in kidney function and alterations to the gut microbiota[10][11][12][13][14][15][16]. The association between kidney disease and changes in the composition of the gut microflora, intestinal environment, and permeability of the gut epithelial barrier occurs via what has been termed the gut–kidney axis[17]. Toxic products generated by a dysbiotic gut may contribute to the progression of chronic kidney disease and its numerous comorbidities.

2. PBUTs and the Gut Microbiome

2.1 Gut Microbial Dysbiosis

The uremic nature of CKD has a profound impact on the intestinal microbiota. The composition of the gastrointestinal microflora is significantly altered in ESRD[10][11][12], and is impacted even in the early stages of kidney disease[13]. Stool samples of healthy controls and ESRD patients exhibited significant differences in 190 bacterial taxa belonging to 23 different families. Lactobacillaceae and Prevotellaceae were lower in ESRD, whereas Enterobacteria and Enterococci taxa increased in colonic abundance by 100-fold[10]. Controlled studies utilizing uremic rats show renal dysfunction itself induces alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota, identifying 175 bacterial OTUs that differed between uremic and control animals[10].

Patients with kidney disease experience intestinal wall edema and congestion, slower transit times, metabolic acidosis, and decreased processing of dietary fibers. Each of these factors alters gut epithelial tight-junctions, affects the translocation of microbial metabolites, and increases intestinal permeability[17]. Together, they impair immune system function and lead to systemic inflammation, which furthers gut dysbiosis and advances kidney damage.

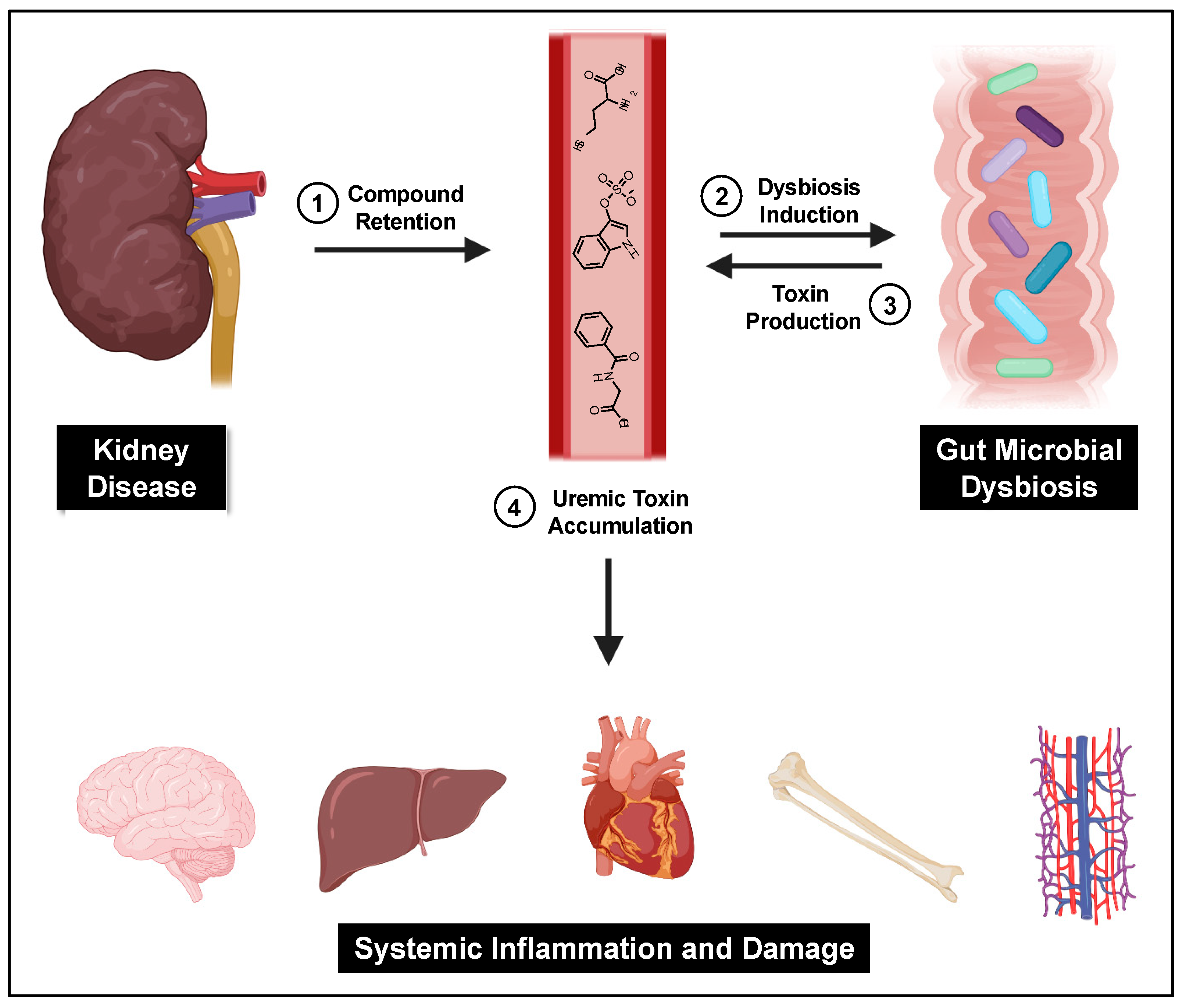

A central cause proposed for gut microbial dysbiosis in CKD patients is bacterial hydrolysis of urea by ureases within the GI tract, leading to increased gut luminal ammonia and increased intestinal pH. A 2014 study found that 63% of the 19 gut microbial families dominant in CKD patients encoded urease genes, and such bacterial communities exhibited an increase in gene products that form indoles and p-cresols along with a reduction in genes that produce the short chain fatty acids that are healthy for colonocytes[18]. Higher gut pH significantly induces the expression of tryptophanase, the enzyme responsible for indole production and subsequent IS formation[19]. Tryptophanase activity is also thought to limit tryptophan availability to the host which can alter serotonin levels[20][21]. Because 95% of serotonin is located in the gut, dysbiosis can impact the function of both the enteric and central nervous systems[22]. Increased intestinal pH further contributes to dysbiosis and has been shown to favor the growth of uremic toxin-forming taxa. Taken together, dysbiosis-induced increases in gut-derived uremic toxins further kidney damage and exert deleterious effects on the vasculature, bone, heart, hepatic metabolism, and brain (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The gut–kidney axis. Impaired kidney function and other CKD-related causes lead to uremic toxin accumulation and gut dysbiosis, which then furthers gut-derived uremic toxin accumulation and subsequent systemic damage.

Figure 1. The gut–kidney axis. Impaired kidney function and other CKD-related causes lead to uremic toxin accumulation and gut dysbiosis, which then furthers gut-derived uremic toxin accumulation and subsequent systemic damage.

Protein digestion, metabolism, and absorption in the small intestine is also impaired in ESRD in both dialysis and non-dialysis patients[23][24]. These factors likely contribute to protein malnutrition, a common problem observed in kidney disease patients. Furthermore, proteins not metabolized or digested in the small intestine progress into the colon, where the higher density of microbial cells produces uremic toxins. Indeed, serum levels of both IS and pCS, which are influenced by diet and intestinal microbes, can be correlated with CKD disease stage and severity[25]. Using serum IS and pCS levels as diagnostic tools predictive of disease progression has been proposed[26]. Interestingly, however, a recent study showed that the levels of the IS and pCS precursors indole and p-cresol did not change in feces and urine as kidney disease progressed[27]. The authors proposed that while the microbial generation of these precursors may not change as disease advances, their retention and conversion into uremic toxins is caused by a progressive decline in kidney function.

Detailed alterations to the composition of the gut microflora vary between CKD patients. Dysbiosis is impacted by several variables including reduced GFR, increased colonic pH, dietary changes, pharmaceutical interventions, and other CKD-related factors[28]. These factors may work in concert to alter the biochemical milieu of the gut, colonic microbial metabolism, and the composition of the microbiota. A recent study showed that the taxa responsible for production of IS and pCS vary between kidney disease patients[29]. Bacteroides and Blautia taxa were correlated with high IS but low pCS levels in the serum, whereas Enterococcus, Akkermansia, Dialister, and Ruminococcus taxa were linked to high pCS and low IS serum levels. These findings are consistent with other reports on taxa capable of producing p-cresol and its precursor 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, which include Ruminococcus and Veillonollaceae[30]. In addition, this study showed that a number of Bacteroides taxa metabolized all three aromatic amino acids to produce p-cresol, IAA, and phenylacetic acid. Indeed, Devlin et al. revealed that nearly 40% of tryptophanases present in the gut are expressed by Bacteroides[31]. However, many Bacteroides species native to the intestine, including B. fragilis, B. vulgatus, and B. caccae, do not express this indole-producing enzyme. Numerous toxin-producing bacteria were shown to be enriched in ESRD patients compared to controls and were correlated with patient clinical parameters[32]. Eggerthella lenta and Fusobacterium nucleatum were the most enriched species in ESRD patients and both taxa play a role in the production of gut-derived PBUTs and their precursors like indole, phenol, and HA. Lastly, Kim et al. correlated serum levels of IS, pCS, and p-cresyl glucuronide to alterations in the gut microbiota of 103 CKD patients with mild, moderate, and severe disease [33]. The authors found that Alistipes and Oscillobacter taxa were correlated with IS and p-cresyl glucuronide levels, and Alistipes, Oscillobacter, and Subdoligranulum taxa correlated with pCS levels. Oscillobacter was suggested to act as a hub in the microbial networks of patients with moderate and severe disease, with its abundance giving rise to other CKD-associated taxa. A deeper understanding of the driver and passenger bacterial species in CKD that express enzymes responsible for PBUT production may lead to targeted treatments to reduce serum accumulation of toxins like IS and pCS.

Alterations in the chemical environment of the gut due to CKD can also impact neuroendocrine pathways, including the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis) and the production of neurotransmitters and neuroactive compounds[34]. The HPA axis is activated in response to stress and stimulates the central nervous system[35]. Because toxic compounds like bacterial peptidoglycans and endotoxins more readily cross the gut endothelial barrier due to the increased permeability associated with CKD, they subsequently stimulate the HPA axis to induce a stress response[36][37]. The short chain fatty acids propionate and butyrate produced by gut microbes alter the expression of peptide-YY, an important regulator of food intake and insulin secretion[38]. Dysbiosis in CKD decreases the expression of genes that are responsible for the production of short chain fatty acids, leading to alterations in peptide-YY levels and impacting the pathophysiology of obesity and diabetes, important risk factors of CKD. Finally, the gut microbiota influences the production of a number of neurotransmitters and neuroactive compounds, including GABA, serotonin, tryptamine, catecholamine, and acetylcholine[39], that together impact homeostasis and blood pressure, factors that significantly affect CKD and cardiovascular disease progression.

Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics have been explored in preclinical and clinical studies as therapeutic strategies for CKD. Their impacts on CKD are measured using gut-derived uremic toxin levels, inflammatory markers, and blood urea nitrogen levels. Results for probiotics are conflicting, with some studies showing their ability to reduce IS and pCS levels[40][41], while others found no beneficial effects[42]. Investigations of prebiotics, food ingredients directed to the microbiota[43], have shown that such compounds caused Stage 3–5 CKD patients to exhibit a reduction in plasma levels of gut-derived uremic toxins, particularly IS and pCS[44][45]. Such interventions are thought to favor the growth of healthy gut microbes that restore barrier function while decreasing levels of bacteria that produce uremic toxins[46]. The use of synbiotics, combinations of pre- and probiotics, in animal models and CKD patients reduces blood urea nitrogen, inflammatory markers, and gut-derived uremic toxin levels [47][48][49].

Diet directly impacts the composition and activity of the gut microbiota. A very low protein diet (0.3 g/kg/day of protein) supplemented with ketoanalogues like ketoleucine and ketoalanine reduced IS serum levels in CKD patients by 37% after only 1 week[50]. Furthermore, 6 months of a low-protein diet in non-dialyzed CKD patients produced a marked decrease in serum pCS levels and favorable changes to the gut microbiota composition[51]. Numerous studies confirm that high protein intake, especially in the form of red meat, increases the production of the gut-derived uremic toxins IS, indoxyl glucuronide, kynurenic acid, quinolinic acid, and pCS[52][53]. Therefore, lowered protein intake and vegetarian diets will likely reduce gut-derived uremic toxin levels. Diets with a high protein-to-carbohydrate ratio favor the prevalence of proteolytic bacteria that produce uremic toxins over saccharolytic bacteria that generate beneficial short chain fatty acids. In contrast, a diet that is high in carbohydrates and whole grain fibers but low in red meat, such as a Mediterranean diet, promotes the growth of saccharolytic taxa that reduce gut-derived uremic toxin levels[54][55].

Integrating a low-protein diet with synbiotic supplementation is a promising tool to correct protein assimilation, control disease progression, and improve gut intestinal barrier integrity. Validation of this approach in a large-scale clinical trial is required to demonstrate reduced uremic toxin levels and better outcomes in CKD patients. Low patient adherence is a serious caveat when prescribing dietary alterations and supplementation, especially in disease states with risk factors such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.

The use of carbon adsorbents and phosphate binders to reduce gut-derived uremic toxins is another strategy employed in CKD. AST-120, a spherical carbon adsorbent, was designed to sequester toxins within the GI tract, reducing their absorption and subsequent accumulation in the serum. A number of preclinical and randomized controlled studies have tested this strategy and results are mixed, with clinical and post-hoc analyses showing toxin reductions [56][57][58] and others, particularly the primary randomized controlled trial, showing no proof of utility for CKD[59][60]. Regardless, AST-120 has been approved for CKD treatment in Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines, and is believed to prolong the time to the initiation of dialysis[58]. Phosphate binders like sevelamer and nicotinamide that sequester phosphate in the GI tract, are believed to improve inflammatory status and may enhance the clearance of uremic toxins. Indeed, studies establish that sevelamer, but not nicotinamide, reduces pCS serum levels but did not impact IS concentrations[61][62][63].

Lubiprostone, an FDA approved ClC-2 chloride channel activator used to treat constipation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome[64], was studied in adenine-induced renal failure mouse models. This bicyclic fatty acid derivative improved fecal and intestinal properties of the animals, promoted the recovery of Lactobacillaceae and Prevotella taxa, and reduced serum levels of IS and HA[65]. Lubiprostone has not been studied in CKD patients to date. For additional information on the relationship between the gut microbiota and CKD, the reader is directed to Plata et al.[66] and Castillo-Rodriguez et al. [67].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/toxins12090590

References

- Mills, K.T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Bundy, J.D.; Chen, C.-S.; Kelly, T.N.; Chen, J.; He, J. A systematic analysis of world-wide population-based data on the global burden of chronic kidney disease in 2010. Kidney Int. 2016, 88, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anothaisintawee, T.; Rattanasiri, S.; Ingsathit, A.; Attia, J.; Thakkinstian, A. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nephrol. 2009, 71, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanholder, R.; De Smet, R.; Glorieux, G.; Argilés, A.; Baurmeister, U.; Brunet, P.; Clark, W.; Cohen, G.; De Deyn, P.P.; Deppisch, R.; et al. Review on uremic toxins: Classification, concentration, and interindividual variability. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 1934–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanholder, R.; Pletinck, A.; Schepers, E.; Glorieux, G. Biochemical and Clinical Impact of Organic Uremic Retention Solutes: A Comprehensive Update. Toxins 2018, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholder, R.; Baurmeister, U.; Brunet, P.; Cohen, G.; Glorieux, G.; Jankowski, J. A bench to bedside view of uremic toxins. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronov, P.A.; Luo, F.J.G.; Plummer, N.S.; Quan, Z.; Holmes, S.; Hostetter, T.H.; Meyer, T.W. Colonic contribution to uremic solutes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, R.D.; Sirich, T.L.; Plummer, N.S.; Meyer, T.W. Characteristics of colon-derived uremic solutes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourde-Chiche, N.; Dou, L.; Cerini, C.; Dignat-George, F.; Vanholder, R.; Brunet, P. Protein-Bound Toxins-Update 2009. Semin. Dial. 2009, 22, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carding, S.; Verbeke, K.; Vipond, D.T.; Corfe, B.M.; Owen, L.J. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 26191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Wong, J.; Pahl, M.; Piceno, Y.M.; Yuan, J.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Ni, Z.; Nguyen, T.-H.; Andersen, G.L. Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, A.; Raj, D.S. The Gut Microbiome, Kidney Disease, and Targeted Interventions. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 25, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, N.D. CKD impairs barrier function and alters microbial flora of the intestine: A major link to inflammation and uremic toxicity. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2012, 21, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrios, C.; Beaumont, M.; Pallister, T.; Villar, J.; Goodrich, J.K.; Clark, A.; Pascual, J.; E Ley, R.; Spector, T.D.; Bell, J.T.; et al. Gut-Microbiota-Metabolite Axis in Early Renal Function Decline. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuuchi, F.; Hida, M.; Aiba, Y.; Koga, Y.; Endoh, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Sakai, H. Intestinal bacteria-derived putrefactants in chronic renal failure. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2002, 6, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strid, H.; Simrén, M.; Stotzer, P.O.; Ringström, G.; Abrahamsson, H.; Björnsson, E.S. Patients with chronic renal failure have abnormal small intestinal motility and a high prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Digestion 2003, 67, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, S. Gut bacterial translocation contributes to microinflammation in experimental uremia. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 2856–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, D.Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.-R.; Vaziri, N.D.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y.-Y. Microbiome-metabolome reveals the contribution of gut–kidney axis on kidney disease. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Piceno, Y.M.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Pahl, M.; Andersen, G.L.; Vaziri, N.D. Expansion of urease- and uricase-containing, indole- and p-cresol-forming and contraction of short-chain fatty acid-producing intestinal microbiota in ESRD. Am. J. Nephrol. 2015, 39, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.H.; Lee, J.-H.; Cho, M.H.; Wood, T.K.; Lee, J. Environmental Factor Affecting Indole Production in Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 2011, 162, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Young, K.D. Indole production by the tryptophanase TnaA in Escherichia coli is determined by the amount of exogenous tryptophan. Microbiology 2013, 159, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, J. Indole as an intercellular signal in microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 426–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. Serotonin in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2009, 16, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bammens, B.; Verbeke, K.; Vanrenterghem, Y.; Evenepoel, P. Evidence for impaired assimilation of protein in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 2003, 64, 2196–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammens, B.; Evenepoel, P.; Verbeke, K.; Vanrenterghem, Y. Impairment of small intestinal protein assimilation in patients with end-stage renal disease: Extending the malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis concept. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.W.; Hsu, K.H.; Lee, C.C.; Sun, C.-Y.; Hsu, H.-J.; Tsai, C.-J.; Tzen, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Wu, M.-S. P-cresyl sulphate and indoxyl sulphate predict progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.N.; Wu, I.W.; Huang, Y.F.; Peng, S.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Ning, H.C. Measuring serum total and free indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate in chronic kidney disease using UPLC-MS/MS. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryp, T.; De Paepe, K.; Vanholder, R.; Kerckhof, F.-M.; Van Biesen, W.; Van De Wiele, T.; Verbeke, F.; Speeckaert, M.; Joossens, M.; Couttenye, M.M.; et al. Gut microbiota generation of protein-bound uremic toxins and related metabolites is not altered at different stages of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 1230–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poesen, R.; Windey, K.; Neven, E.; Kuypers, D.R.; De Preter, V.; Augustijns, P.; D’Haese, P.; Evenepoel, P.; Verbeke, K.; Meijers, B. The Influence of CKD on Colonic Microbial Metabolism. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joossens, M.; Faust, K.; Gryp, T.; Nguyen, A.T.L.; Wang, J.; Eloot, S.; Schepers, E.; Dhondt, A.; Pletinck, A.; Vieira-Silva, S.; et al. Gut microbiota dynamics and uraemic toxins: One size does not fit all. Gut 2019, 68, 2257–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, W.R.; Duncan, S.H.; Scobbie, L.; Duncan, G.; Cantlay, L.; Calder, A.G.; Anderson, S.E.; Flint, H.J. Major phenylpropanoid-derived metabolites in the human gut can arise from microbial fermentation of protein. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, A.S.; Marcobal, A.; Dodd, D.; Nayfach, S.; Plummer, N.; Meyer, T.; Pollard, K.S.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Fischbach, M.A. Modulation of a circulating uremic solute via rational genetic manipulation of the gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Hao, Y.; Qin, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Bian, W.; I Zuo, L.; et al. Aberrant gut microbiota alters host metabolome and impacts renal failure in humans and rodents. Gut 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Kim, H.E.; Park, J.I.; Cho, H.; Kwak, M.-J.; Kim, B.-Y.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, J.P.; Kim, D.K.; Joo, K.W.; et al. The Association between Gut Microbiota and Uremia of Chronic Kidney Disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazani, N.; Savoj, J.; Lustgarten, M.; Lau, W.; Vaziri, N. Impact of Gut Dysbiosis on Neurohormonal Pathways in Chronic Kidney Disease. Diseases 2019, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Vale, W.W. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 383–395. [Google Scholar]

- Mudd, A.T.; Berding, K.; Wang, M.; Donovan, S.M.; Dilger, R.N. Serum cortisol mediates the relationship between fecal Ruminococcus and brain N-acetylaspartate in the young pig. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, N.; Chida, Y.; Aiba, Y.; Sonoda, J.; Oyama, N.; Yu, X.-N.; Kubo, C.; Koga, Y. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraufie, P.; Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Lapaque, N.; Dore, J.; Gribble, F.M.; Reimann, F.; Blottière, H.M. SCFAs strongly stimulate PYY production in human enteroendocrine cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Yun, M.; Oh, Y.J.; Choi, H.J. Mind-altering with the gut: Modulation of the gut-brain axis with probiotics. J. Microbiol. 2018, 56, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, F.; Taki, K.; Niwa, T. Bifidobacterium in gastro-resistant seamless capsule reduces serum levels of indoxyl sulfate in patients on hemodialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003, 41, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hida, M.; Aiba, Y.; Sawamura, S.; Suzuki, N.; Satoh, T.; Koga, Y. Inhibition of the Accumulation of Uremic Toxins in the Blood and Their Precursors in the Feces after Oral Administration of Lebenin®, a Lactic Acid Bacteria Preparation, to Uremic Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis? Nephron 1996, 74, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, N.A.; Carmo, F.L.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; De Brito, J.S.; Dolenga, C.J.; Ferreira, D.D.C.; Nakao, L.S.; Rosado, A.S.; Fouque, D.; Mafra, D. Probiotic Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Double-blind, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial. J. Ren. Nutr. 2018, 28, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davani-Davari, D.; Negahdaripour, M.; Karimzadeh, I.; Seifan, M.; Mohkam, M.; Masoumi, S.J.; Berenjian, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods 2019, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmean, Y.A.; Segal, M.S.; Palii, S.P.; Dahl, W.J. Fiber supplementation lowers plasma p-cresol in chronic kidney disease patients. J. Ren. Nutr. 2014, 25, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirich, T.L.; Plummer, N.S.; Gardner, C.D.; Hostetter, T.H.; Meyer, T.W. Effect of Increasing Dietary Fiber on Plasma Levels of Colon-Derived Solutes in Hemodialysis Patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 9, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafra, D.; Borges, N.; Alvarenga, L.; Esgalhado, M.; Cardozo, L.F.; Lindholm, B.; Stenvinkel, P. Dietary Components That May Influence the Disturbed Gut Microbiota in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, H.; Heidari, F.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Nouri-Majelan, N.; Dehghani, A. Synbiotic Supplementations for Azotemia in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 10, 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Nakabayashi, I.; Nakamura, M.; Kawakami, K.; Ohta, T.; Kato, I.; Uchida, K.; Yoshida, M. Effects of synbiotic treatment on serum level of p-cresol in haemodialysis patients: A preliminary study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 26, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Johnson, D.W.; Morrison, M.; Pascoe, E.M.; Coombes, J.S.; Forbes, J.M.; Szeto, C.-C.; McWhinney, B.C.; Ungerer, J.; Campbell, K.L. Synbiotics Easing Renal Failure by Improving Gut Microbiology (SYNERGY): A Randomized Trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzocco, S.; Piaz, F.D.; Di Micco, L.; Torraca, S.; Sirico, M.L.; Tartaglia, D.; Autore, G.; Di Iorio, B.R. Very Low Protein Diet Reduces Indoxyl Sulfate Levels in Chronic Kidney Disease. Blood Purif. 2013, 35, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.P.; Anjos, J.S.; Cardozo, L.; Carmo, F.L.; Dolenga, C.J.; Nakao, L.S.; Ferreira, D.D.C.; Rosado, A.S.; Eduardo, J.C.C.; Mafra, D. Does Low-Protein Diet Influence the Uremic Toxin Serum Levels From the Gut Microbiota in Nondialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Patients? J. Ren. Nutr. 2018, 28, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mafra, D.; Barros, A.F.; Fouque, D. Dietary protein metabolism by gut microbiota and its consequences for chronic kidney disease patients. Futur. Microbiol. 2013, 8, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandouz, S.; Mohamed, A.M.S.; Zheng, Y.; Sandeman, S.; Davenport, A. Reduced protein bound uraemic toxins in vegetarian kidney failure patients treated by haemodiafiltration. Hemodial. Int. 2016, 20, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurno, E.; Cosola, C.; Dalfino, G.; Gesualdo, L.; Daidone, G.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. What Would You Like to Eat, Mr CKD Microbiota? A Mediterranean Diet, please! Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2014, 39, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chierico, F.; Vernocchi, P.; Dallapiccola, B.; Putignani, L. Mediterranean Diet and Health: Food Effects on Gut Microbiota and Disease Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 11678–11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, G.; Agarwal, R.; Acharya, M.; Berl, T.; Blumenthal, S.; Kopyt, N. A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Ranging Study of AST-120 (Kremezin) in Patients with Moderate to Severe CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2006, 47, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Kazama, J.J.; Omori, K.; Matsuo, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Kawamura, K.; Matsuto, T.; Watanabe, H.; Maruyama, T.; Narita, I. Continuous Reduction of Protein-Bound Uraemic Toxins with Improved Oxidative Stress by Using the Oral Charcoal Adsorbent AST-120 in Haemodialysis Patients. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, M.; Kumakura, S.; Kikuchi, M. Review of the efficacy of AST-120 (KREMEZIN®) on renal function in chronic kidney disease patients. Ren. Fail. 2019, 41, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, G.; Berl, T.; Beck, G.J.; Remuzzi, G.; Ritz, E.; Arita, K.; Kato, A.; Shimizu, M. Randomized Placebo-Controlled EPPIC Trials of AST-120 in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 1732–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, R.H.; Kang, S.W.; Park, C.W.; Cha, D.R.; Na, K.Y.; Kim, S.G.; Yoon, S.A.; Han, S.Y.; Chang, J.H.; Park, S.K.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Oral Intestinal Sorbent AST-120 on Renal Function Deterioration in Patients with Advanced Renal Dysfunction. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenglet, A.; Fabresse, N.; Taupin, M.; Gomila, C.; Liabeuf, S.; Kamel, S.; Alvarez, J.C.; Drueke, T.B.; Massy, Z.A. Does the Administration of Sevelamer or Nicotinamide Modify Uremic Toxins or Endotoxemia in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients? Drugs 2019, 79, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, B.; Cataldi, M.; Riccio, E.; Grumetto, L.; Pota, A.; Borrelli, S.; Memoli, A.; Barbato, F.; Argentino, G.; Salerno, G.; et al. Plasma p-Cresol Lowering Effect of Sevelamer in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Observational Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-J.; Pan, C.-F.; Chuang, C.-K.; Liu, H.-L.; Huang, S.-F.; Chen, H.-H.; Wu, C.-J. Effects of Sevelamer Hydrochloride on Uremic Toxins Serum Indoxyl Sulfate and P-Cresyl Sulfate in Hemodialysis Patients. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2017, 9, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Fu, T.; Tong, W.D.; Liu, B.; Li, C.-X.; Gao, Y.; Wu, J.-S.; Wang, X.-F.; Zhang, A.-P. Lubiprostone Is Effective in the Treatment of Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, E.; Fukuda, S.; Shima, H.; Hirayama, A.; Akiyama, Y.; Takeuchi, Y.; Fukuda, N.N.; Suzuki, T.; Suzuki, C.; Yuri, A.; et al. Alteration of the Intestinal Environment by Lubiprostone Is Associated with Amelioration of Adenine-Induced CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plata, C.; Cruz, C.; Cervantes, L.G.; Ramírez, V. The gut microbiota and its relationship with chronic kidney disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 2209–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Rodríguez, E.; Fernandez-Prado, R.; Esteras, R.; Perez-Gomez, M.V.; Gracia-Iguacel, C.; Fernandez-Fernandez, B.; Kanbay, M.; Tejedor, A.; Lázaro, A.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; et al. Impact of Altered Intestinal Microbiota on Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. Toxins 2018, 10, 300.