Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Integrative & Complementary Medicine

|

Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems

|

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Coriandrum sativum (C. sativum), belonging to the Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) family, is widely recognized for its uses in culinary and traditional medicine. C. sativum contains various phytochemicals such as polyphenols, vitamins, and many phytosterols, which account for its properties including anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and analgesic effects.

- cardiovascular

- integrative medicine

- metabolism syndrome

- Ethnopharmacology

- Phytochemistry

- cardiology

- Coriander

- Apiaceae

- cilantro

- Chinese parsley

1. Introduction

Coriandrum sativum Linn. (C. sativum) or coriander, is recognized for its wide range of uses in culinary as well as traditional medicine in a variety of conditions [1]. Different chemical compounds have been identified in each part of the plant including roots, leaves, fruits, and seeds, which account for its broad spectrum of uses [2]. To name a few, such compounds include gallic acid, thymol, and bornyl acetate, which are expected to exert anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and autonomic relaxation induction effects, respectively [3][4][5]. Linalool, a terpene alcohol found in coriander, has been reported to be the main constituent that is responsible for some therapeutic values of coriander as it possesses neuroprotective, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and analgesic effects [6][7][8][9].

It is believed that every part of the plant possesses different nutritional and medicinal values; thus, it was traditionally consumed in diverse areas. Notably, coriander was used in India for relieving gastrointestinal discomfort, respiratory, and urinary complaints; additionally, in some areas of Pakistan, the whole plant of coriander has folk medicinal uses to treat flatulence, dysentery, diarrhea, and vomiting [10][11]. On the other hand, with its distinctive scent and flavor, coriander is often added to food in the culinary industry as a seasoning and a preservative agent; it can be used in the form of leaves and seeds, ground, or as a whole [12]. Furthermore, the powdered fruit of C. sativum has been used as a flavoring agent to mask the taste of some foods such as fish, meat, and baking recipes [13].

According to the World Health Organization [14] (WHO, 2019), the major cause of mortality worldwide is cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). CVDs are a group of heart and blood vessel disorders including coronary and peripheral artery diseases, rheumatic, cerebrovascular, and congenital heart disease, in addition to deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism [15]. Despite possessing various health benefits which have been reported in many research and review papers [16][17][18], the cardioprotective effects of coriander have never been summarized in terms of the anti-atherogenic, antihypertensive, antiarrhythmic, and hypolipidemic effects [19]. Phytochemicals present in C. sativum, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, phytosterols, and terpenes, have significant potential in cardiovascular health and have demonstrated an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibiting potency, cardioprotective, antihyperlipidemic, and cardiometabolic disorder-inhibiting properties [20][21][22][23].

2. Botanical Description and Taxonomy

C. sativum belongs to the Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) family, which is herbaceous and grows annually, with a height of 20–70 cm (Table 1). C. sativum is known as “coriander” or “Chinese parsley” in English; “cilantro” in Spanish; “kusthumbari” or “dhanya” in Sanskrit; “dhane” in Bengali; “pak chee” in Thailand; and “Yánsuī”, “Yán qiàn”, “Hú suī”, or “Xiāngcài” in Chinese [1][2][24]. It is thought to have originated in the regions of the Middle East and the Mediterranean, where its growth may have broadened to China, Europe, India, Africa, and Asia; nevertheless, several authors have considered coriander as a weed in cereals, and its origin is still not clear [25]. The leaves are green with a variable lanceolate shape and glabrous surfaces, while the flowers are white or pink in umbels with asymmetrical shapes (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [2][18]. Meanwhile, the seeds are dry schizocarps with two mericarps with oval-shaped globules. Furthermore, the stems of C. sativum are pale green with hollow branches and a glabrous surface [24].

Figure 1. (A) C. sativum flowers (by Andrey Zharkikh). (B) C. sativum half and whole seeds (by ZoyaChubby). From North Carolina Extension Gardner: Plant toolbox. (https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/coriandrum-sativum/, accessed on 20 December 2021).

Figure 2. The leaves of Coriandrum sativum (by Forest and Kim Starr). From North Carolina Extension Gardner: Plant toolbox. (https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/coriandrum-sativum/, accessed on 20 December 2021).

Table 1. The taxonomical classification of C. sativum is as follows.

| Scientific Name: | Coriandrum sativum |

|---|---|

| Common names: | Coriander, Chinese Parsley, cilantro, kusthumbari, dhanya, dhane, pak chee, yuan sui, hu sui |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Subkingdom: | Tracheobionta |

| Superdivision: | Spermatophyta |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Subclass: | Rosidae |

| Order: | Apiales |

| Family: | Apiaceae/Umbelliferae |

| Genus: | Coriandrum L. |

| Species: | Coriandrum sativum L. |

3. Ethnomedicinal Uses

C. sativum was used as one of the earliest spices by humans. Traditionally, C. sativum seeds were consumed to relieve pain, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammation [26], whereas the decoction of coriander was believed to treat mouth ulcers and eye redness [27]. The seeds have been prescribed to relieve gastrointestinal disorders such as flatulence, diarrhea, indigestion, and nausea [28]. Coriander is believed to exert these actions by stimulating the liver to increase the secretion of bile and other digestive enzymes which escalate the action of the digestive system, hence shortening the time of food passage through the gastrointestinal tract [29]. In countries such as Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Morocco, coriander was also known to lower blood glucose levels [30][31][32], have antimicrobial properties against food-borne pathogens, such as Salmonella, in addition to aphrodisiac and analgesic power [33]. Furthermore, coriander has been used traditionally in Turkey and India to relieve indigestion [34]; increase water excretion; and prevent seizures, anxiety, and sleeplessness [35][36]. Moreover, it has been documented of C. sativum in Morocco being used traditionally in the treatment of diabetes, indigestion, flatulence, insomnia, renal disorders, loss of appetite, and as a diuretic [37]. Detailed traditional uses of C. sativum are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Traditional uses of C. sativum in different countries.

| Traditional Uses | Area | Plant Parts Used | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis, inflammation, and joint pain | India | Seeds/seeds aqueous extract | [26][38][39] |

| For measles, diabetes, aerophagy, gastroenteritis | China | The whole plant parts | [40] |

| Antiviral and neuro-energizer | Pakistani herbal drugs (Intellan) | Aerial parts of the plant | |

| Some liver diseases | - | Aqueous extract of the roasted seeds | |

| Carminative, diuretic, dyspeptic complaints, loss of appetite, convulsion, insomnia, and anxiety and in medical purposes | Iranian traditional medicine | Powdered seeds or dry extract | [38] |

| Diaphoretic, diuretic, carminative, and stimulant activity | Iranian traditional medicine | The whole plant parts | [37][41] |

| Diuretic and for some renal diseases | Morocco | Oral administration of plant parts | [42] |

| Mouth ulcer and eye redness | - | leaves decoction | [27] |

| Grounded as an ingredient of curry powder and gingerbread, also a component of liquesces and spirits. Aromatic ingredient of tobacco and perfumes. In Unani medicine to quench thirst and for melancholia. |

India | Seeds and aqueous infusion of leaves | [39] |

| Stimulant and carminative; stomachic, antibilious, digestive stimulant | India | Leaves | [29] |

| Lower blood glucose levels | Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Morocco | Fruits, decoction of leaves and seeds | [30][31][32] |

| Aphrodisiac, analgesic, antimicrobial properties | - | The volatile oil | [33] |

| Appetizer, Digestive, Carminative | Turkey | Infusion of the seeds | [34] |

| For anxiety, sedative and muscle relaxant effect | - | The aqueous extract | [35][36] |

| Treats Influenza, bad breath, unpleasant odor from genitalia | Traditional Chinese Medicine | Seeds | [43] |

| Against worm and to treat rheumatism | The European pharmacopeia | Fruits | |

| Stimulates gastric secretion, treats gastric ulcers and mouth infections | Asian region | Essential oils |

4. Phytochemistry

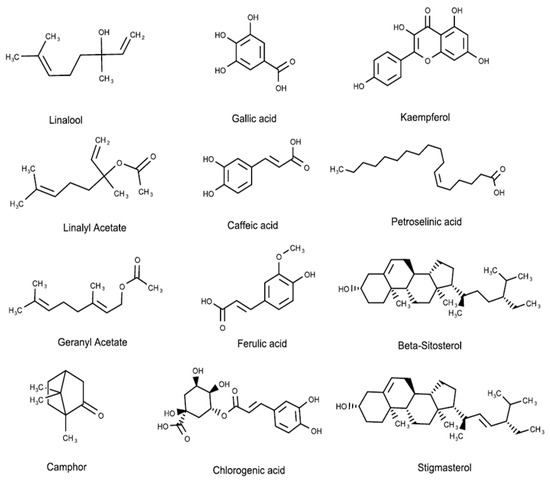

Recent studies revealed that different kinds of alkaloids, essential oils, fatty acids, flavonoids, phenolics, reducing sugars, sterols, tannins, and terpenoids were extracted from C. sativum [16][44]. In particular, the leaves were reported to have an abundant concentration of folates, ascorbic acid, gallic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, and chlorogenic acid. Additionally, the investigation of the water-soluble components of C. sativum seeds showed the presence of 33 compounds, including monoterpenoid, monoterpenoid glycosides and glucosides, and aromatic compound glycosides such as norcarotenoid glucoside [45]. In the vegetative part of the C. sativum, different phenolics and flavonoids were detected in significantly high concentrations, such as quercetin diverse glycosides (405.36–3296.16 mg/kg), kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside (320.86 mg/kg), in addition to ferulic acid glucoside and p-coumaroylquinic acid [46]. Another study of the polyphenolic contents of coriander grass showed that a 40% ethanol extract contains many flavonoids (0.13% to 10.71%), coumarins (1.4% to 6.83%), and phenolcarboxylic acids (7.24% to 13.51%) [47]. Anthocyanin was also characterized in coriander leaves, and the concentration was found to be influenced by salicylic acid, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc fertilizers [48]. Figure 3 and Table 3 present the different phytochemical structure classes of C. sativum.

Figure 3. Phytochemical molecular structures extracted from C. sativum, such as terpenes, phenolic acids, flavonoids, fatty acids, and phytosterols.

These constituents of C. sativum were extracted by different methods, including solvent extraction such as n-hexane, water, and methanol, in addition to supercritical gases, microwave-assisted extraction, sonication, and hydrodistillation [20][49][50][51][52][53][54]. Essential oils (EOs) and fatty oils were the most significant components in the fruit, with a content of 0.03–2.6% and 9.9–27.7%, respectively [55]. Different EO chemotypes were detected in coriander seeds, including ketones, aliphatic aldehydes, aliphatic hydrocarbon, aliphatic alcohols, esters, monoterpene hydrocarbons, monoterpene oxides, monoterpene alcohols, monoterpene esters, and sesquiterpenes, with linalool as the main monoterpene alcohol extracted in high quantities [56]. The highest percentage of EO that has been yielded from coriander seeds was cultivated in Tunisia with a linalool content of 87.54% [57], while 73.1%, 40.9–79.9%, 37.65%, and 69.60% of linalool was extracted from C. sativum from Algeria, Iran, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, respectively [58][59][60].

EOs are obtainable by extracting different parts of the plant using hydrodistillation extraction [10], subcritical water, Soxhlet apparatus [61], solvent extraction, steam distillation, and supercritical CO2 methods [62]. However, the EO content is variable among different parts of the plant, which could be due to the different origins of cultivated varieties, climate and geographical conditions [10][63], the area and season of cultivation, the degree of plant maturation, and genotypes of the species. In particular, 2-dodecenal was found as the main volatile EO in the root and stalk, while 1-ethenyl-cyclododecanol was the highest volatile component in the leaves of C. sativum [64]. Furthermore, different percentages, components, and immunotoxicity were identified in oils extracted from the leaves than the stems’ EO extracts of the Korean C. sativum [65]. In addition, the essential oil yields and efficiencies of commercial coriander fruits from different countries were extracted and found to be different according to the geographical area [66]. The relationship between some environmental conditions in Argentina and the essential oil composition of two coriander landraces (European and Argentinean) has been studied [67]. It has also been found that genotypic and phenotypic variations contributed to the variety of essential oils’ concentrations, in addition to the interaction from other environmental conditions, such as fertilizers, weediness, and soil degradation. Likewise, the phenolic contents of the two C. sativum varieties, vulgare and microcarpum, were found to be similar but with different concentrations of the main phenolic compounds, namely quercetin-3-b-d glucoside and quercetin-3-O-glucuronide [68]. On top of that, the average EO yields for vulgare fruits (0.1% to 0.5%) are lower than that of the microcarpum (0.8–2.1%) [16]. Details of the total phytochemical constituents of C. sativum are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Main phytochemical constituents of C. sativum classified according to their chemical class, including the plant part that was extracted and the extraction method.

| Phytochemical Components | Chemical Class | Plant Part | Extraction Solvent/Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferulic acid, Gallic acid, and Caffeic acid | Phenolic acids | Above-ground parts | Ether, ethyl acetate, butanol, and 2-ethyl acetate extracts | [47] |

| Salicylic acid | Benzoic acid derivative | |||

| Esculetin, Esculin, Scopoletin 4-Hydroxycoumarin, Umbelliferone, and Dicoumarin |

Coumarins | |||

| Hyperoside, rutin, hesperidin, vicenin, diosmin, luteolin, apigenin, orientine, dihydroquercetin, catechin, and arbutin | Flavonoids | |||

| β-carotene and total carotenoids | Carotenoids | Leaves at mature and young plant stage, fresh and dry seeds | Ice-cold acetone was then partitioned against petroleum ether. | [69] |

| α-, β-, γ- δ- tocopherols, and α-, γ-tocotrienols | Tocols | Whole fruit, pericarp, and seeds | Extracted with n-hexane | [70] |

| Petroselinic acid, linoleic acid, palmitic acid, and oleic acid | Fatty acids | Boiled in water, then grounded using a mixture of chloroform/methanol/hexane and finally separated by thin-layer chromatography | ||

| Stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, δ-stigmasterol | Sterols | Seed and pericarp of coriander fruit | Extracted with n-hexane in a Soxhlet apparatus | [71] |

| Linalool, camphor, and geraniol | Essential oils | Hydrodistillation followed by extraction with 2-methylbutane |

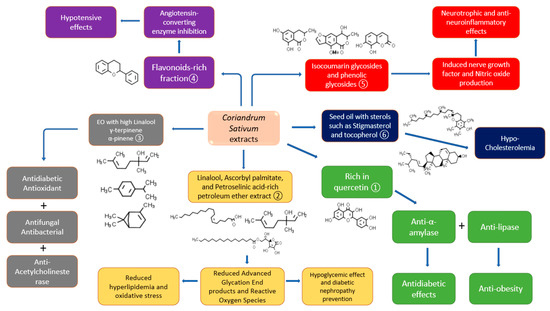

Different studies involved the characterization of C. sativum phytochemicals in the extracts that were employed in bioactivity determination. However, very few studies involved the bioactivity-guided isolation of a specific compound that is responsible for that pharmacological action. Quercetin-rich aqueous ethanolic extract was found beneficial in α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition and thus has a potential antidiabetic effect [72]. The extract also contained some other flavonoid compounds such as vanillic acid, caffeic acid, and p-coumaric acid, whereas the total phenolic content was 2.68 ± 0.07 mg GAE/g DW. Lipase inhibition activity for 1 mg/mL of aqueous ethanol was 55.76 ± 1.40% which indicates a significantly strong anti-obesity property. In the same study, the angiotensin-converting enzyme was inhibited by coriander extracts to 70.66 ± 2.34% which shows that the polyphenolic-rich extract can be beneficial for hypertension in vitro. Moreover, the diabetic nephropathy prevention and hypolipidemic activities were illustrated in the petroleum ether extract of C. sativum seeds that are rich in linalool, ascorbyl palmitate, and petroselinic acid [73]. The saturation of hexokinase enzymes due to diabetes leads to the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which when interacting with their receptors cause vascular aging and renal damage [74]. From the above-mentioned study, it was found that linalool in addition to other terpenes and fatty acids has the potential to bind with the RAGE receptor and subsequently block AGEs’ damaging action. In a different study, the Eos’ major components of C. sativum were linalool, γ-terpinene, and α-pinene with prominent activities against diabetes, microbial infections, and acetylcholinesterase enzyme [75]. Other activities such as hypotensive [20] and neuroprotective ones [76] were detected in flavonoids- and isocoumarin glycosides-containing fractions of C. sativum, respectively. The isocoumarin glycosides cilantroside A and B, in addition to the phenolic glycosides daphnin and benzyl-O-β-d-glucoside, have been found to stimulate nerve growth factor as the main neurotrophic factor which is related to nerve growth, maintenance, and neuronal survival. Moreover, the aglycones of the isocoumarins showed anti-inflammatory effects in addition to more significant neurotrophic properties than their glycosides. Figure 4 indicates the details on studies performed on C. sativum with the characterization or isolation of the phytochemicals in the respective extract/fraction.

Figure 4. The role of C. sativum phytochemicals in some of its biological activities from different studies ① Suttisansanee, Thiyajai, Chalermchaiwat, Wongwathanarat, Pruesapan, Charoenkiatkul and Temviriyanukul [72], ② Kajal and Singh [73], ③ Hajlaoui, Arraouadi, Noumi, Aouadi, Adnan, Khan, Kadri and Snoussi [75], ④ Hajlaoui, Arraouadi, Noumi, Aouadi, Adnan, Khan, Kadri and Snoussi [75], ⑤ Cha, Yoon, Kim, Kim and Lee [76], and ⑥ Ramadan, et al. [77].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules27010209

References

- Prachayasittikul, V.; Prachayasittikul, S.; Ruchirawat, S.; Prachayasittikul, V. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum): A promising functional food toward the well-being. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 305–323.

- Mandal, S.; Mandal, M. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) essential oil: Chemistry and biological activity. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 421–428.

- Riella, K.R.; Marinho, R.R.; Santos, J.S.; Pereira-Filho, R.N.; Cardoso, J.C.; Albuquerque-Junior, R.L.; Thomazzi, S.M. Anti-inflammatory and cicatrizing activities of thymol, a monoterpene of the essential oil from Lippia gracilis, in rodents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 656–663.

- Matsubara, E.; Fukagawa, M.; Okamoto, T.; Ohnuki, K.; Shimizu, K.; Kondo, R. (−)-Bornyl acetate induces autonomic relaxation and reduces arousal level after visual display terminal work without any influences of task performance in low-dose condition. Biomed. Res. 2011, 32, 151–157.

- Sun, G.; Zhang, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, W. Gallic acid as a selective anticancer agent that induces apoptosis in SMMC-7721 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 150–158.

- de Lucena, J.D.; Gadelha-Filho, C.V.J.; da Costa, R.O.; de Araujo, D.P.; Lima, F.A.V.; Neves, K.R.T.; de Barros Viana, G.S. L-linalool exerts a neuroprotective action on hemiparkinsonian rats. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharm. 2020, 393, 1077–1088.

- Souto-Maior, F.N.; de Carvalho, F.L.; de Morais, L.C.; Netto, S.M.; de Sousa, D.P.; de Almeida, R.N. Anxiolytic-like effects of inhaled linalool oxide in experimental mouse anxiety models. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2011, 100, 259–263.

- Souto-Maior, F.N.; Fonseca, D.V.; Salgado, P.R.; Monte, L.O.; de Sousa, D.P.; de Almeida, R.N. Antinociceptive and anticonvulsant effects of the monoterpene linalool oxide. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 63–67.

- Li, X.J.; Yang, Y.J.; Li, Y.S.; Zhang, W.K.; Tang, H.B. alpha-Pinene, linalool, and 1-octanol contribute to the topical anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of frankincense by inhibiting COX-2. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 179, 22–26.

- Laribi, B.; Kouki, K.; M’Hamdi, M.; Bettaieb, T. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) and its bioactive constituents. Fitoterapia 2015, 103, 9–26.

- Khan, S.W.; Khatoon, S. Ethnobotanical studies on some useful herbs of Haramosh and Bugrote valleys in Gilgit, northern areas of Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2008, 40, 43.

- Singletary, K. Coriander: Overview of potential health benefits. Nutr. Today 2016, 51, 151–161.

- Mahendra, P.; Bisht, S. Coriandrum sativum: A daily use spice with great medicinal effect. Pharmacogn. J. 2011, 3, 84–88.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Rahman, F.A.; Abdullah, S.S.; Manan, W.; Tan, L.T.; Neoh, C.F.; Ming, L.C.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H.; Salmasi, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Cyclosporine in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 238.

- Wei, J.N.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhao, Y.P.; Zhao, L.L.; Xue, T.K.; Lan, Q.K. Phytochemical and bioactive profile of Coriandrum sativum L. Food Chem. 2019, 286, 260–267.

- Khazdair, M.R.; Anaeigoudari, A.; Hashemzehi, M.; Mohebbati, R. Neuroprotective potency of some spice herbs, a literature review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2019, 9, 98–105.

- Sahib, N.G.; Anwar, F.; Gilani, A.H.; Hamid, A.A.; Saari, N.; Alkharfy, K.M. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.): A potential source of high-value components for functional foods and nutraceuticals—A review. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 1439–1456.

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S. Herbs Used for the Treatment of Hypertension and their Mechanism of Action. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19, 77.

- Hussain, F.; Jahan, N.; Rahman, K.U.; Sultana, B.; Jamil, S. Identification of hypotensive biofunctional compounds of Coriandrum sativum and evaluation of their Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibition potential. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 4643736.

- Agunloye, O.M.; Oboh, G.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Ademosun, A.O.; Akindahunsi, A.A.; Oyagbemi, A.A.; Omobowale, T.O.; Ajibade, T.O.; Adedapo, A.A. Cardio-protective and antioxidant properties of caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid: Mechanistic role of angiotensin converting enzyme, cholinesterase and arginase activities in cyclosporine induced hypertensive rats. Biomed. Pharm. 2019, 109, 450–458.

- Micallef, M.A.; Garg, M.L. Beyond blood lipids: Phytosterols, statins and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid therapy for hyperlipidemia. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 927–939.

- Oliveira, J.R.; Ribeiro, G.H.M.; Rezende, L.F.; Fraga-Silva, R.A. Plant Terpenes on Treating Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease: A Review. Protein Pept. Lett. 2021, 28, 750–760.

- Al-Snafi, A.E. A review on chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of Coriandrum sativum. IOSR J. Pharm. 2016, 6, 17–42.

- Diederichsen, A. Coriander: Coriandrum sativum L.; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 1996; Volume 3.

- Nair, V.; Singh, S.; Gupta, Y.K. Anti-granuloma activity of Coriandrum sativum in experimental models. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2013, 4, 13–18.

- Paniagua-Zambrana, N.Y.; Bussmann, R.W.; Romero, C. Coriandrum sativum L. A piaceae. Ethnobot. Andes 2020, 1–7.

- Musselman, L.J. Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients Used in Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics, 2nd ed.; Leung, A.T., Foster, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1996.

- Platel, K.; Srinivasan, K. Digestive stimulant action of spices: A myth or reality? Indian J. Med. Res. 2004, 119, 167–179.

- Otoom, S.; Al-Safi, S.; Kerem, Z.; Alkofahi, A. The use of medicinal herbs by diabetic Jordanian patients. J. Herb. Pharmacother. 2006, 6, 31–41.

- Tahraoui, A.; El-Hilaly, J.; Israili, Z.; Lyoussi, B. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used in the traditional treatment of hypertension and diabetes in south-eastern Morocco (Errachidia province). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 110, 105–117.

- Al-Rowais, N.A. Herbal medicine in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 1327–1331.

- Chaudhry, N.; Tariq, P. Bactericidal activity of black pepper, bay leaf, aniseed and coriander against oral isolates. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 19, 214–218.

- Ugulu, I.; Baslar, S.; Yorek, N.; Dogan, Y. The investigation and quantitative ethnobotanical evaluation of medicinal plants used around Izmir province, Turkey. J. Med. Plants Res. 2009, 3, 345–367.

- Emamghoreishi, M.; Heidari-Hamedani, G. Anticonvulsant effect of extract and essential oil of Coriandrum sativum seed in conscious mice. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2004, 3, 71.

- Emamghoreishi, M.; Heidari-Hamedani, G. Sedative-hypnotic activity of extracts and essential oil of Coriander seeds. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2006, 31, 22–27.

- Aissaoui, A.; El-Hilaly, J.; Israili, Z.H.; Lyoussi, B. Acute diuretic effect of continuous intravenous infusion of an aqueous extract of Coriandrum sativum L. in anesthetized rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 115, 89–95.

- Taherian, A.A.; Vafaei, A.A.; Ameri, J. Opiate system mediate the antinociceptive effects of Coriandrum sativum in mice. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2012, 11, 679.

- Wichtl, M. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals: A Handbook for Practice on a Scientific Basis; Wichtl, M., Ed.; Medpharm GmbH Scientific Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2004.

- Khare, C.P. Indian Medicinal Plants: An Illustrated Dictionary; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008.

- Grieve, M. A Modern Herbal; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 2.

- Hassar, M. La phytothérapie au Maroc. Espérance Médicale 1999, 6, 83–85.

- Bashir, S.; Safdar, A. Coriander Seeds: Ethno-medicinal, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile. Sci. Spices Culin. Herbs-Latest Lab. Pre-Clin. Clin. Stud. 2020, 2, 39–64.

- Chauhan, P.; Jaryal, M.; Kumari, K.; Singh, M. Phytochemical and in vitro Antioxidant Potential of Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Brassica juncea and Coriandrum sativum; World Vegetable Center: Tainan, Taiwan, 2012.

- Ishikawa, T.; Kondo, K.; Kitajima, J. Water-soluble constituents of coriander. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 32–39.

- Barros, L.; Duenas, M.; Dias, M.I.; Sousa, M.J.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C. Phenolic profiles of in vivo and in vitro grown Coriandrum sativum L. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 841–848.

- Oganesyan, E.; Nersesyan, Z.; Parkhomenko, A.Y. Chemical composition of the above-ground part of Coriandrum sativum. Pharm. Chem. J. 2007, 41, 149–153.

- Rahimi, A.R.; Babaei, S.; Mashayekhi, K.; Rokhzadi, A.; Amini, S. Anthocyanin content of coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) leaves as affected by salicylic acid and nutrients application. IJB 2013, 3, 141–145.

- Patel, D.K.; Desai, S.N.; Gandhi, H.P.; Devkar, R.V.; Ramachandran, A.V. Cardio protective effect of Coriandrum sativum L. on isoproterenol induced myocardial necrosis in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3120–3125.

- Jabeen, Q.; Bashir, S.; Lyoussi, B.; Gilani, A.H. Coriander fruit exhibits gut modulatory, blood pressure lowering and diuretic activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 122, 123–130.

- Rehman, N.; Jahan, N.; ul-Rahman, K.; Khan, K.M.; Zafar, F. Anti-arrhythmic potential of Coriandrum sativum seeds in salt induced arrhythmic rats. Pak. Vet. J. 2016, 36, 465–471.

- Shrirame, B.; Geed, S.; Raj, A.; Prasad, S.; Rai, M.; Singh, A.; Singh, R.; Rai, B. Optimization of Supercritical Extraction of Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) Seed and Characterization of Essential Ingredients. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 330–344.

- Coelho, J.P.; Cristino, A.F.; Matos, P.G.; Rauter, A.P.; Nobre, B.P.; Mendes, R.L.; Barroso, J.G.; Mainar, A.; Urieta, J.S.; Fareleira, J.M.; et al. Extraction of volatile oil from aromatic plants with supercritical carbon dioxide: Experiments and modeling. Molecules 2012, 17, 10550–10573.

- Sourmaghi, M.H.; Kiaee, G.; Golfakhrabadi, F.; Jamalifar, H.; Khanavi, M. Comparison of essential oil composition and antimicrobial activity of Coriandrum sativum L. extracted by hydrodistillation and microwave-assisted hydrodistillation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 2452–2457.

- Coşkuner, Y.; Karababa, E. Physical properties of coriander seeds (Coriandrum sativum L.). J. Food Eng. 2007, 80, 408–416.

- Burdock, G.A.; Carabin, I.G. Safety assessment of coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) essential oil as a food ingredient. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 22–34.

- Msaada, K.; Hosni, K.; Taarit, M.B.; Chahed, T.; Kchouk, M.E.; Marzouk, B. Changes on essential oil composition of coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) fruits during three stages of maturity. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 1131–1134.

- Zoubiri, S.; Baaliouamer, A. Essential oil composition of Coriandrum sativum seed cultivated in Algeria as food grains protectant. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 1226–1228.

- Nejad Ebrahimi, S.; Hadian, J.; Ranjbar, H. Essential oil compositions of different accessions of Coriandrum sativum L. from Iran. Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 24, 1287–1294.

- Bhuiyan, M.N.I.; Begum, J.; Sultana, M. Chemical composition of leaf and seed essential oil of Coriandrum sativum L. from Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2009, 4, 150–153.

- Eikani, M.H.; Golmohammad, F.; Rowshanzamir, S. Subcritical water extraction of essential oils from coriander seeds (Coriandrum sativum L.). J. Food Eng. 2007, 80, 735–740.

- Msaada, K.; Taârit, M.B.; Hosni, K.; Salem, N.; Tammar, S.; Bettaieb, I.; Hammami, M.; Limam, F.; Marzouk, B. Comparison of Different Extraction Methods for the Determination of Essential oils and Related Compounds from Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.). Acta Chim. Slov. 2012, 59, 803–813.

- Benyoussef, E.H.; Saibi, S. Influence of essential oil composition on water distillation kinetics. Flavour Fragr. J. 2013, 28, 300–308.

- HuaSong, S.; Yue, Z.; WenZhong, Z.; ShengQiang, D.; Kai, S.; ZhongXiao, T.; Yan, Y.; Ying, H. Changes of volatile components in Eryngium foetidum L. and Yunnan Coriandrum sativum L. with different plant organs. Food Res. Dev. 2016, 37, 161–165.

- Chung, I.-M.; Ahmad, A.; Kim, S.-J.; Naik, P.M.; Nagella, P. Composition of the essential oil constituents from leaves and stems of Korean Coriandrum sativum and their immunotoxicity activity on the Aedes aegypti L. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2012, 34, 152–156.

- Orav, A.; Arak, E.; Raal, A. Essential oil composition of Coriandrum sativum L. fruits from different countries. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2011, 14, 118–123.

- Gil, A.; De La Fuente, E.B.; Lenardis, A.E.; López Pereira, M.; Suárez, S.A.; Bandoni, A.; Van Baren, C.; Di Leo Lira, P.; Ghersa, C.M. Coriander essential oil composition from two genotypes grown in different environmental conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2870–2877.

- Saygi, K.O. Quantification of Phenolics from Coriandrum sativum vulgare and Coriandrum sativum microcarpum by HPLC–DAD. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 2021, 45, 1319–1326.

- Divya, P.; Puthusseri, B.; Neelwarne, B. Carotenoid content, its stability during drying and the antioxidant activity of commercial coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) varieties. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 342–350.

- Sriti, J.; Wannes, W.A.; Talou, T.; Mhamdi, B.; Hamdaoui, G.; Marzouk, B. Lipid, fatty acid and tocol distribution of coriander fruit’s different parts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 294–300.

- Sriti, J.; Talou, T.; Wannes, W.A.; Cerny, M.; Marzouk, B. Essential oil, fatty acid and sterol composition of Tunisian coriander fruit different parts. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1659–1664.

- Suttisansanee, U.; Thiyajai, P.; Chalermchaiwat, P.; Wongwathanarat, K.; Pruesapan, K.; Charoenkiatkul, S.; Temviriyanukul, P. Phytochemicals and In Vitro Bioactivities of Aqueous Ethanolic Extracts from Common Vegetables in Thai Food. Plants 2021, 10, 1563.

- Kajal, A.; Singh, R. Coriandrum sativum seeds extract mitigate progression of diabetic nephropathy in experimental rats via AGEs inhibition. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213147.

- Singh, R.; Kaur, N.; Kishore, L.; Gupta, G.K. Management of diabetic complications: A chemical constituents based approach. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 150, 51–70.

- Hajlaoui, H.; Arraouadi, S.; Noumi, E.; Aouadi, K.; Adnan, M.; Khan, M.A.; Kadri, A.; Snoussi, M. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Anti-Acetylcholinesterase, Antidiabetic, and Pharmacokinetic Properties of Carum carvi L. and Coriandrum sativum L. Essential Oils Alone and in Combination. Molecules 2021, 26, 3625.

- Cha, J.M.; Yoon, D.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, K.R. Neurotrophic and anti-neuroinflammatory constituents from the aerial parts of Coriandrum sativum. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 105, 104443.

- Ramadan, M.F.; Amer, M.M.A.; Awad, A.E.S. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) seed oil improves plasma lipid profile in rats fed a diet containing cholesterol. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 227, 1173–1182.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!