Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Public, Environmental & Occupational Health

|

Health Policy & Services

|

Health Care Sciences & Services

Arthropod-borne viral (arboviral) diseases are a significant global health problem accounting for >17% of all infectious disease cases and 1 million deaths worldwide annually. Arboviral diseases are infections caused by over 100 viruses belonging to the Flaviviridae, Togaviridae, Reoviridae, Bunyaviridae, Rhabdoviridae and Orthomyxoviridae families. These viruses are spread to humans through arthropods, including mosquitos, ticks, and flies.

- arboviral diseases

- public health

- surveillance

- Pacific islands

- dengue

- Zika

- chikungunya

- outbreaks

- low- and middle-income countries

1. Dengue Outbreaks

Dengue virus is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus, primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. Four DENV serotypes have been identified; all can cause the full spectrum of disease [21]. WHO estimates there are 50–100 million cases and over 20,000 deaths due to dengue infection annually [22].

Dengue outbreaks of varying duration and serotype have been reported in the PICs since the late 1800s [18,19]. Historically, dengue outbreaks in PICs have had a cyclic pattern with one serotype dominating, being replaced every 3–5 years [19]; however, in 2014 Dupont-Rouzeyrol et al. reported this pattern had changed with co-circulation of serotypes becoming common [23]. Roth et al. (2014) identified 18 outbreaks of different serotypes occurring over the 2012–2014 period including, for the first time on record, all four DENV serotypes circulating at once [20,24]. Exposure to one serotype of dengue does not result in immunity to another serotype, leaving populations vulnerable to reinfection [19]. There is further evidence that those who have been infected with multiple serotypes are at increased risk of severe dengue infection [25,26].

During the study period, dengue was the most commonly reported arboviral disease; almost all (19 out of 22) PICs reported at least one dengue outbreak event. In total, our review identified 72 DENV outbreaks—15 DENV-1, 20 DENV-2, 14 DENV-3, four DENV-4, and an additional 19 outbreaks with undetermined serotype—suggesting the pattern identified by Dupont-Rouzeyrol et al. of co-circulation has continued (Figure 2).

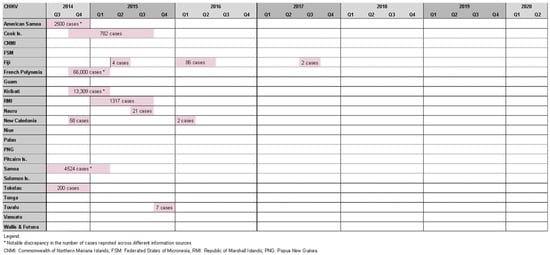

Figure 2. Timeline of reported dengue outbreaks (confirmed/suspected and unspecified cases) in Pacific island countries and areas, October 2014–June 2020.

All four dengue serotypes were co-circulating across the Pacific Island region in 2016, 2017, and 2018; and DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-unspecified were co-circulating in 2014, 2015, 2019 and 2020 (Figure 2). In the study period, six PICs recorded co-circulation of two or more DENV serotypes (Cook Islands [27], Fiji [27,28], French Polynesia [27,29], New Caledonia [27,30,31], PNG [27,28,31,32,33,34], and Solomon Islands [27,28,31,33]; and two confirmed co-circulations of all four DENV serotypes (PNG 2016 [27,28,31,32,33,34], New Caledonia 2018 [27,28]).

Dengue outbreaks ranged from less than 10 to more than 12,250 cases (due to limited testing capacity, suspected case numbers were often reported). New Caledonia was the PIC that reported the most outbreaks (n = 13) (Figure 2) [27,28,30,31].

Of the 72 dengue outbreaks reported, case numbers were available for 55. At least 1000 cases were reported in 18 outbreaks, and 16 outbreaks had less than 100 cases.

During the study period, the largest dengue outbreak on record in the PICs occurred in the Solomon Islands in 2016/17. This outbreak is reported to have affected at least 12,329 people, resulting in 877 hospitalizations and 16 deaths [27,31,33]. Another notable outbreak occurred in Guam in 2019, which although small (18 cases), is considered important as it was the first autochthonous outbreak of the disease in Guam in 75 years [27].

PNG reported two separate periods of co-circulation of four and then three DENV serotypes in 2016 and 2018, respectively. The first episode of co-circulating dengue was from January to June of 2016 [27,28,31,32,33,34], followed by cases of DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-4, and DENV-unspecified in 2018 (Figure 2) [27]. Curiously, no outbreaks were reported in PNG outside of these times. This may suggest periods of no dengue circulation; however, this seems unlikely and contradicts more recent evidence suggesting the persistent circulation of DENV-1, DENV-2, and DENV-3 in PNG for over a decade [32,33]. This is significant as endemic PNG strains serve as a potential reservoir for the spread of the virus to other countries, as demonstrated by molecular epidemiology studies that have linked outbreaks in Australia, Solomon Islands, and Fiji [32,35]. Further research is needed to understand the circulation of dengue in PNG, including elucidating the genetic diversity of strains and the potential risk for their regional dissemination.

Where Information about Dengue Outbreaks Was Found

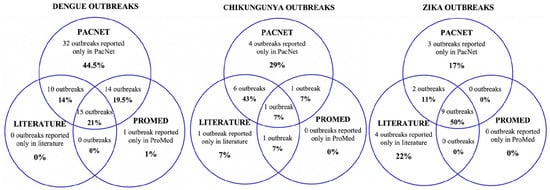

Seventy-one of the 72 dengue outbreaks were reported as situation reports and updates on PacNet, usually within days of their detection. Therefore, outbreak information was brief and limited, mostly reporting case numbers for that week for a particular disease. Twenty-five out of the seventy-two outbreaks are featured in the peer-reviewed literature. These articles were understandably published well after the events (three months to three years later), were usually published as ‘event reports’, and contained more comprehensive and richer data than PacNet reports. Less than half (n = 30) of the dengue outbreaks were featured on ProMed, and none were featured on WHO’s Disease Outbreak News (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sources of data reporting dengue, chikungunya and Zika outbreaks (confirmed/suspected and unspecified cases) in Pacific Island countries and areas, October 2014–June 2020. Note: In addition, one Zika outbreak was reported in WHO’s Disease Outbreak News [37]; this event was not reported on PacNet or ProMed but did feature in peer reviewed literature [38,39].

Data across the different sources were often conflicting. For example, information on PacNet about a dengue outbreak in American Samoa in 2016 reported 809 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmed cases with no mention of any other syndromic cases. However, two years later, Cotter et al. (2018) reported 3240 outbreak-associated suspected cases based on syndromic surveillance data [36].

2. Chikungunya Outbreaks

Chikungunya virus is transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected Aedes mosquito, most commonly Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, although Ae. polynesiensis can also transmit the virus [40,41]. Chikungunya infections usually manifest as a self-limiting dengue-like illness with high fever, severe arthralgias, myalgias, and maculopapular rash. Rare but severe complications may occur [2,41].

Roth et al. reported seven chikungunya outbreaks between 2012 and 2014 [20]. We found 14 outbreaks in the study period affecting 11 PICs: three outbreaks in Fiji [42], two in New Caledonia [27], and one in each of America Samoa [27], Samoa [27], Tokelau [27], French Polynesia [27], Cook Islands [27,29], Kiribati [27], Marshall Islands [27], Nauru [27], and Tuvalu [27] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Timeline of reported chikungunya outbreaks (confirmed/suspected and unspecified cases) in the Pacific Island countries and areas, October2014–June 2020.

While half of these events resulted in relatively small outbreaks (affecting <100 people), there were also notable epidemics. The most striking occurred in French Polynesia from October 2014 to March 2015, affecting an estimated 66,000 people (estimated attack rate = ~25%) [43], and resulted in 64 admissions to intensive care and 18 deaths [44]. Health authorities observed a four- to nine-fold increase in Guillain–Barre syndrome (GBS) cases at the time, raising suspicion of a causal relationship with chikungunya infection. This was the second suspected arbovirus-triggered outbreak of GBS in French Polynesia, following Zika-associated cases in 2013/14 [45]. American Samoa (2500 cases) [46], Samoa (4524 cases) [27], the Cook islands (782 cases) [27], and Tokelau (200 cases) [47] experienced chikungunya outbreaks at a similar time raising suspicion of regional spread; however, this was disproven by genomic analysis that found the French Polynesian outbreak was epidemiologically linked to the Caribbean, suggesting the infection was imported by a traveler [43].

Other notable chikungunya outbreaks were reported in Kiribati (13,309 cases) [27], the Marshall Islands (1317 cases) [27], New Caledonia, (est. 58 cases) [27], and Fiji (86 cases) [42]. Cases were also identified in Queensland (Australia), and New Zealand among travelers recently returned from a PIC [27].

A serological survey conducted in Fiji in 2013 by Kama et al. soon after the first chikungunya cases were detected in the country found population antibody seroprevalence rates to be low (<1%), suggesting minimal exposure had occurred and that the population was immunologically naïve to CHIKV [48]. A follow-up serosurvey conducted in June 2017 (after two outbreaks in Fiji) found a seroconversion rate of 15.5% [42].

Where Information about Chikungunya Outbreaks Was Found

3. Zika Outbreaks

First isolated from a non-human primate in 1947 in Africa, human Zika infections had only been reported in 14 human cases (all in Africa) until 2007 [50] when the first documented large outbreak of the disease occurred in Yap State, Federated States of Micronesia [51]. Subsequently, Zika has spread to other PICs through international travelers and trade, with Roth et al. reporting three outbreaks (in Cook Islands, New Caledonia and French Polynesia) between 2012 and 2014 [20].

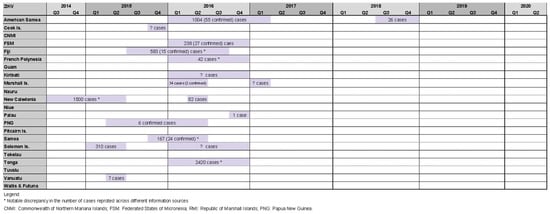

Our review identified 18 Zika outbreaks affecting 14 PICs, with four countries experiencing two outbreak events during the study period (American Samoa 2016/17 and 2018, RMI 2016 and 2017, New Caledonia 2014/15 and 2016, Solomon Islands 2015 and 2016). Zika outbreaks in Tonga 2016 [27,28,33,38,39], New Caledonia 2014/15 [27,52,53], and American Samoa 2016/17 [27,28,33,39,54,55] reported relatively high case counts of 2420, 1500, and 1004, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Timeline of reported Zika outbreaks (confirmed/suspected and unspecified cases) in the Pacific island countries and areas, October 2014–June 2020.

Zika-associated cases of microcephaly among newborn children in French Polynesia in 2013–2014, and subsequent Zika-associated GBS in South America in late 2015/early 2016 led World Health Organization of a ‘public health emergency of international health concern’ [3,4], triggering enhanced public health and clinical response measures globally.

In 2019, Sheel et al. linked the emergence of Zika in PICs to environmental stresses caused by climate change and associated pressures on fragile public health systems [56]. Craig et al. (2017) tested a hypothesis that in the absence of a dedicated surveillance system, routinely collected data on the incidence of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), a cardinal sign of GBS, may provide a useful early warning indicator for Zika-related neurological complications. However, the authors found no conclusive evidence to support this hypothesis [39].

Where Information about Zika Outbreaks Was Found

A total of 14 out of 18 Zika outbreaks identified were reported on PacNet [27], 15 out of 18 outbreaks were reported in the literature [33,38,39,48,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59], and 11 outbreaks were reported on both PacNet and in the literature. Nine outbreaks were reported on ProMed mail [28], and only one of the Zika outbreaks was reported in WHO’s Disease Outbreak News [37] (Figure 3).

Interestingly, six Zika event-related posts on PacNet reported the identification of the virus in international travelers arriving into Australia or New Zealand from a PIC where local transmission had not recently been reported [27], suggesting that ZIKV may have been circulating undetected in those countries. This highlights the value of regional disease intelligence sharing for the early detection of emergent pathogens of outbreak potential.

In 2016, Musso et al. reported the analysis of blood collected from French Polynesian blood donors. They found 42 out of 1505 asymptomatic blood donors (2.8%) were PCR positive for ZIKV [59]. This suggests that community transmission of Zika continued in French Polynesia well after communication about the outbreak ceased in mid-2014 [27].

4. Other Arboviral Disease Outbreaks

The review did not find definitive evidence of other arboviral outbreaks; however, the likely circulation of Ross River Virus (RRV) in French Polynesia [60] and Barmah Forest Virus in PNG [61] was mentioned in the literature.

The suspicion of RRV circulation was supported by Aubry et al. (2017), which presents serological evidence of circulation among the French Polynesian population before 2014 [62]. Lau et al. (2017) suggest that diagnosing RRV, if present, would be unlikely as most PICs lack the capacity to perform serology to confirm infection with the virus [63]. Further, symptomatic surveillance would likely lack sensitivity given the similarity in symptom profiles with other more expected arboviral infections. With 55% to 75% of RRV infections being asymptomatic, symptom-based surveillance methods are likely inadequate [60].

A report by Caly et al. (2019) found evidence that Barmah Forest virus, a virus that has never been detected outside Australia, was circulating in PNG [61].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pathogens11010074

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!