Neuropathic pain affects from 33% to 88% of pediatric patients undergoing dinutuximab infusion. Pain usually manifests as allodynia, which involves various regions of the body, especially the abdomen, extremities, back, and chest, and then spreads peripherally to the ankles and feet [

18,

32,

37,

42,

43,

44]. Anti-GD2 induced pain is characterized by mechanical allodynia without thermal hyperalgesia [

23].

It usually begins within an hour from the start of dinutuximab beta infusion and is limited to the time of administration of this drug, ending shortly after the termination of the infusion; it usually occurs during the first infusion of the drug and decreases after each course [

22]. A retrospective study on 26 patients affected by high-risk neuroblastoma who received dinutuximab based immunotherapy concluded that grade ≥3 (of a 1 to 5 scale) pain occurs in about 88% of patients during immunotherapy course 1, but in 42% of patients during course 5 [

42].

The pain-inducing mechanism is unclear. It probably involves the same immune response by ADCC and CDC elicited for treatment; the antigen–anti-GD2-antibody complex on the GD2-expressing nerve fibers is thought to be the first trigger for pain (Figure 2a–c).

It is possible that patients who benefit from dinutuximab treatment are those with a high percentage of neuroblastoma cells that are GD2 positive [

45]. Nevertheless, not all patients with progressive neuroblastoma will have high expression of GD2 on tumor cells [

46]. Thus, such patients may have toxicity with no benefit from dinutuximab. Furthermore, the selective pressure of dinutuximab therapy may result in decreased GD2 expression, which has already been observed with targeting CD20 on lymphoma with rituximab, targeting CD19 on leukemia with CAR-T cells, and with antibodies to EGF in breast cancer [

47,

48,

49].

Prevention and Treatment

Because of the high frequency of neuropathic pain during dinutuximab beta infusion, various strategies of prevention and treatment have been evaluated.

First, a continuous 10-day infusion appeared more tolerable than the discontinuous 5-day infusions on consecutive days. Mueller et al. compared data from 53 patients with high-risk neuroblastoma who received continuous 10-day infusions of dinutuximab beta with those of 226 patients from the study by Yu et al. who received discontinuous once-daily infusions of dinutuximab on 4 consecutive days [

18,

50]. The incidence of treatment-related adverse events was lower with the continuous infusion than with the once-daily infusion; particularly, the incidence of neuropathic pain decreased from 51.8% of patients under once-daily infusion to 37.7% of patients under continuous infusion.

Furthermore, as one of the mechanisms of generation of neuropathic pain seems to be the complement activation at the GD2-expressing nerve fibers level [

51], humanized anti-GD2 antibodies (hu14.18K322A) have been shown to resolve pain more rapidly, through reduction of complement activation, even though opioid requirements were not reduced [

32,

52]. Moreover, initial data show some complete responses in the treatment of recurrent or refractory neuroblastoma, but a randomized trial is needed to determine if the elimination of complement binding may maintain anti-GD2 activity in addition to decreasing neuropathic pain [

53,

54].

Aggressive pain control is such a priority that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends permanent discontinuation of dinutuximab in patients with severe pain that is uncontrollable by analgesic therapy.

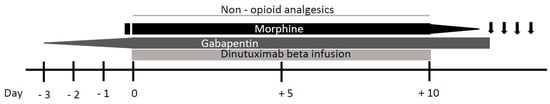

Because neuropathic pain usually occurs at the beginning of the treatment, its onset can be predicted and premedication with analgesics should be administered. Triple therapy with gabapentin, non-opioid analgesics, and opioids is recommended for pain treatment [

22] (

Figure 3). Three days prior to dinutuximab beta infusion, oral gabapentin administration should be started at the dose of 10 mg/kg/day. The next day, the dose is increased to 10 mg/kg for two daily administrations and the next day to 10 mg/kg for three daily administrations (the maximum single dose of gabapentin must not exceed 300 mg). Gabapentin reverses the tactile allodynia that follows anti-GD2 administration; its administration should be continued as long as required by the patient and be tapered off up to suspension after weaning off intravenous morphine infusion [

24].

Figure 3. Neuropathic pain management during continuous dinutuximab beta infusion. Gabapentin administration is started three days prior to dinutuximab beta infusion and increased up to 10 mg/kg for three daily administrations. After a bolus, morphine is commenced just before dinutuximab beta infusion and continued as a 24 h intravenous infusion (0.03 mg/kg/h). Following reduction of its infusion rate, morphine is stopped 4 h after the end of dinutuximab beta infusion. If neuropathic pain persist after the intravenous morphine weaning off, oral morphine sulphate or tramadol can be administered on demand.

Non-opioid analgesics such as paracetamol or ibuprofen should be used during the treatment.

The use of opioids for the duration of antibody therapy given as continuous infusion over 10 days is essential for pain control, with higher opioid doses given in the first infusion day and course than in subsequent days and courses. Morphine should be commenced 2 h before dinutuximab beta infusion with a bolus of 0.02–0.05 mg/kg. Subsequently, continuous intravenous morphine infusion should be started at a dosing rate of 0.03 mg/kg/h and continued during all dinutuximab beta infusion. In response to patient’s pain perception, it may be necessary to increase the infusion rate or, on the other hand, it could be possible to wean off morphine over 5 days, progressively decreasing its dosing rate. If continuous morphine infusion is required for more than 5 days, treatment should be gradually reduced by 20% per day after the last day of dinutuximab beta infusion.

In the case of neuropathic pain persisting after the intravenous morphine is weaned off, oral morphine sulphate (0.2–0.4 mg/kg every 4–6 h) or tramadol (for moderate neuro-pathic pain) can be administered on demand.

For subsequent courses, analgesic therapy at the highest dose of opioid required for adequate pain control during the prior course should be considered at the start and then modulated according to the severity of pain [

55].

Other analgesic regimens were experimented but, to our knowledge, the previous is the best strategy for prevention and treatment of dinutuximab beta-related neuropathic pain. Opioid transdermal delivery system has not been utilized as it is not adjustable on the basis of patients’ variable pain intensity [

56,

57].

The concurrent administration of low-dose lidocaine has been shown to reduce opioid consumption in neuroblastoma patients treated with immunotherapy, but it determined a very high incidence of vomiting and may not be appropriate in the ward setting [

24]. Gorges and colleagues studied the use of dexmedetomidine and hydromorphone to manage the pain associated with anti-GD2 infusion. They reported adverse effects such as hypotension, hypoxemia, and bradycardia in 30%, 8%, and 4% of treatment days, respectively [

58]. Bertolizio et al. retrospectively analyzed the efficacy of a multimodal regimen with gabapentin, ketamine, and morphine for preventing and treating neuropathic pain during dinutuximab therapy [

59]. Even if the addition of ketamine to opioids is known to decrease morphine consumption and pain, this study showed higher morphine consumption and a lower incidence of moderate and severe pain with fewer adverse effects in comparison with data by Georges et al.; this may be due to avoidance of dexmedetomidine [

58,

60].