1. Introduction

Surface modification by applying coatings is used in manufacturing industries to enhance surface properties. Surface coatings protect the base material and save cost with respect to component replacement, material degradation and service life of the coated components [

1,

2,

3,

4]. There are several coating techniques such as active screen plasma treatment, physical vapor deposition (PVD), thermal spray and laser deposition techniques that are used according to specific requirements such as coating thickness, type of bonding, bonding strength, material to be coated, temperature of the coating process and desired properties of the coating [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Methods based on atomic and vapor deposition such as active screen plasma nitriding, chemical vapor deposition, PVD, and conventional plasma nitriding are recommended for thin films; while methods based on particle deposition such as laser cladding, high velocity oxygen fuel spray, wire-arc spray, and cold spray (CS) are recommended for thick coatings [

8,

9]. Recent (2021) and most prominent techniques for the development of thin films and thick coatings, which work on lower deposition temperatures as compared to their conventional counterparts, are active plasma screen treatment and CS.

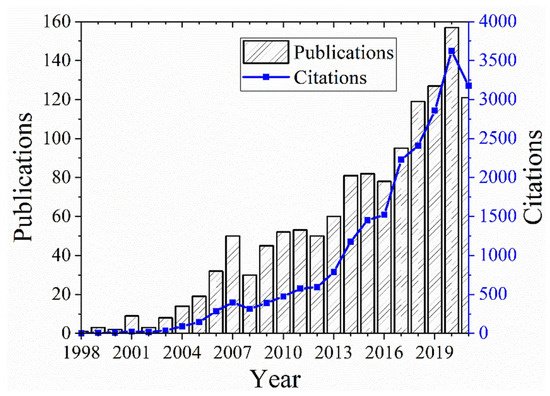

The CS process was developed in the mid-1980s by the Siberian division of the Russian Academy at the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, whereas it emerged in North America in the 1990s [

10,

11]. In the early 1990s, Russian scientists from the Obninsk Center for Powder Spraying (OCPS) innovated CS equipment that was more economic [

11], which enabled the onsite repair of defective components. Introduction of this equipment made Russia the lead manufacturers of CS systems. The development and use of CS systems outside Russia were initiated in the early 2000s. Subsequently, there was an increasing interest in CS technology that resulted in an exponential growth in publications and citations (

Figure 1).

The CS process uses a high pressure supersonic gas jet to accelerate fine powder particles at or above a critical velocity (500–1200 m/s) for their deposition as a coating. The kinetic energy released during the impact of the particle upon the substrate ruptures any surface oxides and plastically deforms the particle as it approaches the clean surface of the substrate; hence promoting bonding of a coating [

12,

13,

14].

The formation of a CS coating consists of two steps; (i) initial particle-substrate contact that is followed by (ii) particle-particle interactions. In the first step, bonding/adhesion at the interface of the substrate and first layer of the particles is attained, followed by the formation of consecutive layers by particle-particle interactions [

15,

16,

17,

18]. These layer-by-layer formations result in thick coatings [

19,

20].

Successful deposition of cold sprayed particles is accomplished when they strike the substrate at a velocity greater than the critical velocity for a given feedstock material. The critical velocity depends on the properties of the material and its morphology [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Moreover, the characteristics of the oxide layer on the particle surface also determines its critical velocity [

18]. Yu et al. [

25] found that greater oxide layer thicknesses, requires a higher critical velocity to achieve effective bonding at the interface. Particle impact, oxide-layer breakdown, particle deformation, bond formation or interlocking at the interface, localization of strain and densification of the coating layers are the parameter responsible for an effective CS deposition [

15,

17,

26,

27,

28,

29].

CS has been used to produce protective coatings and performance enhancing surface modifications, ultra-thick coatings, free forms and near net shapes. CS is a relatively young technology and further R&D is still needed to understand and control the process; as well as, to develop engineered coatings with desired properties for specific applications. Government laboratories, academic institutions, and industries have undertaken considerable R&D efforts [

30,

31,

32].

CS technology has demonstrated potential for the deposition of thick metallic/non-metallic coatings with enhanced properties when compared to methods such as thermal spray and laser cladding [

7,

33]. CS offers oxide-free coatings because processing can be accomplished in the solid state [

28,

34,

35,

36]. Further, CS provides dense coatings with porosities as low as <1% achievable [

2,

36,

37]. It has been reported that material properties of cold sprayed materials are comparable with those of their counterpart bulk materials.

CS of soft and ductile materials on a soft substrate (i.e., a soft-on-soft interface) is most successful compared to hard-on-hard, soft-on-hard, and hard-on-soft interfaces [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Coating of brittle materials on hard-interfaces (a hard-on-hard interface), the effect of residual stresses on the coating properties, and delamination of thick coatings remain technical challenges [

33,

42,

43,

44]. However, a wide range of materials such as copper, titanium, steel, and high entropy alloys can be cold sprayed by optimizing the spray parameters, substrate conditions and feedstock conditions [

5,

36,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

2. Adhesion Mechanism in Cold Spray

CS is a solid-state deposition process since the feedstock is not melted; however, the kinetic energy of the high velocity particles leads to interfacial deformation as well as localized heat at the location of impact [

17,

51,

52]. The conversion of kinetic energy into deformation and heat results in mechanical interlocking as well as metallurgical bonding at the interface [

53]. The bonding at the interface in CS is still mysterious to some degree since there is no exact theory that explains the bonding mechanism at the interface. However, the literature mentions that the spray particles require a certain amount of energy in combination with a critical velocity at an optimum temperature, for effective bonding to occur [

12,

13,

14,

32]. High strain rate deformation is observed around the particle-substrate interface, which produces a microscopic protrusion of material with localized heating. The combination of material deformation at the atomic level and localized heat may lead to metallurgical bonding [

54,

55].

Bonding at the interface is governed by the severe plastic deformation of the materials; which, with associated adiabatic shear instability (ASI) at the interface, leads to the metal-jet formation [

12,

17,

39,

56]. The high velocity particle impacts cause breakage of the native oxide layer at the surfaces, providing a particle-to-substrate contact. This true contact of the particles with the substrate may lead to the jet formation that is governed by ASI [

16,

20,

28]. However, Hassani-Gangaraj et al. [

57] contradicted the work of Assadi et al. [

13] and Grujicic et al. [

15] by reporting that ASI is not necessary for bonding in CS. Responding to the comments of Assadi et al. [

58], Hassani-Gangaraj et al. [

59] defended their simulation-based research that supported ASI was not required for bonding. These, and other scientific contradictions highlight that adhesion mechanism(s) of CS coatings is an unresolved topic that requires further investigation.

Delamination and poor adhesion strength of soft-on-hard and hard-on-hard interfaces are of great concern for industries such as the marine, nuclear, aerospace, automotive and electronics. Thus, understanding the mechanism of bonding can address the issue of poor adhesion and delamination, which would assist the advanced manufacturing sector. For instance, thick copper coatings on steel (SS316L) plates that would exhibit properties comparable to that of bulk Cu, along with good adhesion, are in high demand for the vacuum vessel of Tokamaks [

9,

55,

60,

61,

62]. In this regard, Singh et al. [

63] investigated the bonding mechanism of Cu particles on steel substrates (soft-on-hard interface) by altering the CS parameters and the substrate conditions.

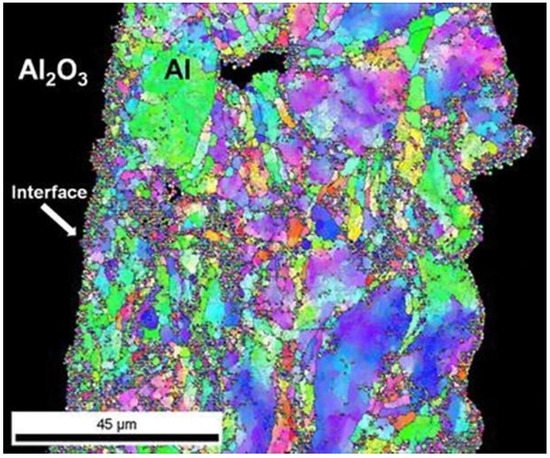

Drehmann et al. [

19], Wustefled et al. [

41] and Dietrich et al. [

49] investigated the bonding mechanism for cold sprayed Al on an Al

2O

3 substrate (soft-on-hard). Their results revealed that bonding of Al particles on super-finished monocrystalline sapphire substrate occurred due to deformation-induced recrystallization in the vicinity of the particle-substrate interface, as represented in

Figure 2. The formation of nano-sized grains at the vicinity of the interface assists metallurgical bonding, which results in improved adhesion strength between ductile Al particles and the Al

2O

3 monocrystalline ceramic substrate. Therefore, there are many factors that influence the adhesion strength, and these need optimization to achieve the best adhesion strength of the CS coating.

Pre-treatments are used: for example, modifying the substrate surface roughness by grit blasting, pre-heating the substrate to circumvent the residual stress evolution, and adjusting the substrate hardness by thermal treatment [

64,

65,

66]. CS input parameters such as particle velocity, gas temperature, nozzle geometry, stand-off-distance, particle size and morphology, and type of the process gas play significant roles in the quality of the final coating and the bonding mechanism at the interface [

46,

67,

68,

69].

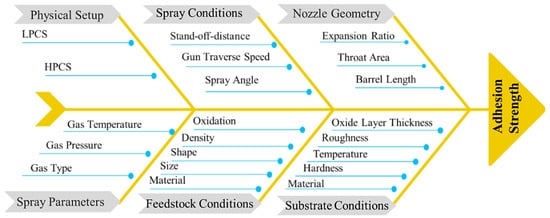

Additionally, the type and model of the CS system influence the bonding mechanism [

70]. There are several parameters (highlighted in

Figure 3) that influence the bonding mechanism and these need to be adjusted for specific particle-substrate combinations.