Myopia is caused by excessive eye growth. Single vision lenses can fully correct the myopic refractive error. Moreover, single vision lenses were investigated as myopia control method and control effects were compared between full-, over-, under- and un-correction. Study results are controversial, however, no beneficial effect of over-, under- and un-correction of myopia were found. Considering ethical reasons in children as well, current clinical advice is directed towards full-correction of myopia if single vision lenses are the correction method of choice.

- optometry

- single vision lenses

- refractive error

- myopia

Definitions

Myopia

Refractive errors are present when the ocular axial length does not match the ocular focal length. Subsequently, the focal point is not located on the retina, but rather more anterior (myopia) or posterior (hyperopia) relative to the retina. In case of myopia, this is commonly caused by an elongated eye, due to excessive eye growth. The overshoot of eye growth ("myopia progression") comes along with structural retinal changes, eventually leading to an increased risk of potentially blinding pathologies, such as retinal detachments, macular degeneration, glaucoma and cataract [1][2]. Therefore, various so-called "optical myopia control interventions" have been under research, in order to slow down eye growth and myopia progression [3]. One of these strategies are conventional single vision spectacle lenses. Usually, these are used for full-correction of refractive error, however, varying degrees of the amount of correction were investigated as myopia control intervention in children.

Single vision spectacle lenses

Single vision spectacle lenses are a non-invasive, simple and affordable technique for optically correcting refractive errors, such as myopia. Here, a negative lens shifts the ocular focal point on the central retina. Spectacles are well-established [4][5] and their working principle barely varies over time. Nonetheless, the WHO estimated in 2008 that around 153 million people over five years of age were considered as visually impaired as a result of uncorrected refractive errors [6].

History and background

Since the beginning of the 20th century [7][8], it has been speculated that the usage of spectacles may provoke the eyes to become lazier, weakening eyesight and subsequently inducing a higher degree of myopia. While the general public retains this idea [9], research on this topic has shown controversial results since then. During the last decades, the complex interactions of myopia and its progression have been gradually unveiled. Although some major questions still need to be solved, one main hypothesis prevails: the emmetropization process is over-ruled by a closed retinal feedback loop between blur and eye growth, mainly driven by the amplitude and sign of defocus [10]. While the exact mechanisms of how the retina interprets the blur, or whether defocus is the major contributor or just a mediator, have not been clarified yet [11], some authors have adventured into modelling in order to examine how full correction of the refractive error may disrupt this loop [12].

Latest research data

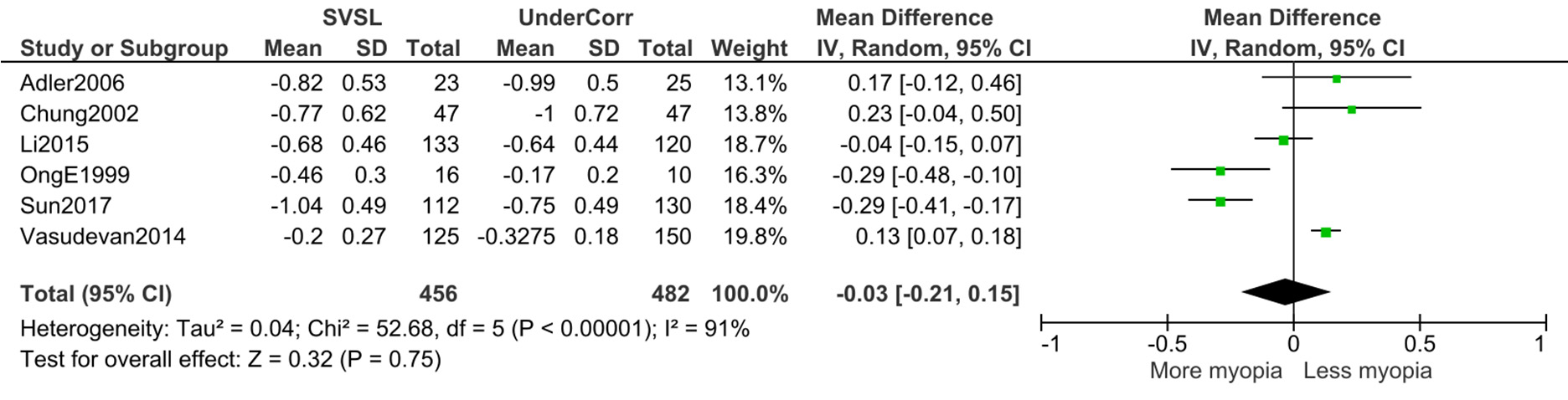

For instance, Medina’s model [12] proposes that continuous correction of myopia using single-vision spectacles would exacerbate the myopic condition. On the other hand, published clinical trials, which evaluated under-correction, did not find such a clear relationship, as shown in Figure 1, revealing a non-significant influence on the refractive error of the eye refraction.

Figure 1. Forest plot displaying the refractive shift between different studies that reported data on under-correction versus single vision spectacle wear (Adler 2006 [13], Chung 2002 [14], Li 2015 [15], Ong 1999 [16], Sun 2017 [17] and Vasudevan 2014 [18]).

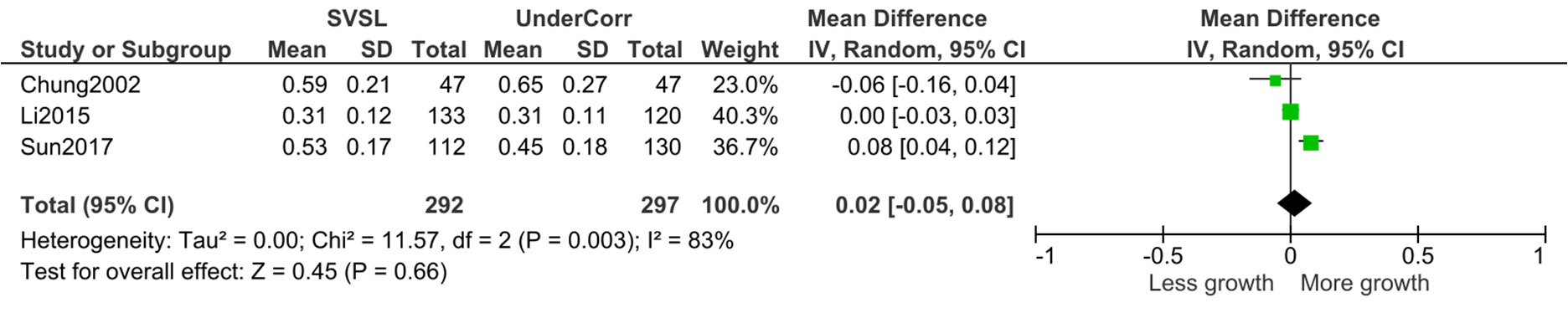

Still, a small trend can be elicited if the studies are sub-grouped, as shown in Supplementary Data 1 (S1). Thus, a significant change can be observed when the amount of under-correction is more than 1 dioptre and even more when the amount exceeds 1.5 dioptres, making the spectacles that are worn act in a myopigenic manner. Furthermore, the axial length presents a non-significant change that can be observed across studies, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Forest plot displaying the axial length shift between different studies that reported data on under-correction versus single vision spectacle wear (Chung 2002 [14], Li 2015 [15], Sun 2017 [17]).

It is noteworthy that a few other studies that report about under-correction vs. full correction were excluded for the following reasons: (A) the possibility that monovision in monocular conditions [19] may influence eye development has not been clarified yet and, thus, it represents another confounding factor; (B) language and data availability [20] (although other studies cited it, it is only available in Japanese) and; (C) age of the subjects [21], as the emmetropization process is assumed to finish around the age of six years, with myopia onset appearing around eight years of age [22]. Therefore, an intervention before this age cannot be compared with other groups whose subjects are aged from 7 to 13 years, such as those in the included studies.

Another independent systematic review [23] also evaluated the overall outcome of studies with over-, mono-, un- and under-correction versus full-correction in terms of refractive shifts. No positive effect of under-correction was proven, one study even found faster myopia progression. However, one study compared anisomyopes (myopes with a refractive error difference between both eyes of more than 1 D), who were fully corrected on one eye, but only under-corrected on the other eye. Here, under-correction seemed to slow myopia progression. Regarding complete un-correction of myopic children, studies are very controversial with opposite results, with increased or decreased progression of myopia. However, research can agree that there is no benefit in over-correction of myopia, which is expected due to the defocus theory. Due to the equivocal results, full-correction is advised, if myopic children are corrected with single vision lenses [23].

Ethical considerations

Leaving a child with un- or under-corrected myopia represents an ethical dilemma, because of reduced quality of life [28]. Moreover, the poor vision caused by leaving the children not fully corrected or even under-corrected should not limit, incapacitate or deteriorate school performance and daily life activities [29]. For instance, a limit could be set at 1.00 dioptre, which is similar to a deterioration of visual acuity of ≤ 0.5 LogMAR [30][31]. This visual acuity is at the borderline of the

distance visual acuity demand for children sitting in the first row of a typically sized classroom [32].

Conclusion

To conclude, until more evidence is obtained, the ethical limitations surrounding under-correction or non-correction and the unclear outcomes from the literature should preclude the clinical practice from recommending leaving the subjects not fully corrected.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm9061975

References

- Seang-Mei Saw; Gus Gazzard; Wei-Han Chua; Edwin Chan Shih-Yen; Myopia and associated pathological complications. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 2005, 25, 381-391, 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00298.x.

- D.I. Flitcroft; The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2012, 31, 622-660, 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.06.004.

- Jinhai Huang; Daizong Wen; Qinmei Wang; Colm McAlinden; Ian Flitcroft; Haisi Chen; Seang Mei Saw; Hao Chen; Fangjun Bao; Yune Zhao; et al. Efficacy Comparison of 16 Interventions for Myopia Control in Children. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 697-708, 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.11.010.

- Melvin L. Rubin; Spectacles: Past, present, and future. Survey of Ophthalmology 1986, 30, 321-327, 10.1016/0039-6257(86)90064-0.

- Charles E. Letocha; The origin of spectacles. Survey of Ophthalmology 1986, 31, 185-188, 10.1016/0039-6257(86)90038-x.

- Serge Resnikoff; Donatella Pascolini; Silvio P Mariotti; Gopal P Pokharel; Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2008, 86, 63-70, 10.2471/BLT.07.041210.

- Fuchs, Ernst. Textbook of Ophthalmology, 2nd ed.; Duane (translator), Eds.; Appleton: New York, 1892; pp. /.

- Edward Jackson; The full correction of myopia. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 1893, 106, 297-306, 10.1097/00000441-189309000-00005.

- Does wearing glasses weaken your eyesight? . BBC. Retrieved 2020-8-7

- Josh Wallman; Jonathan Winawer; Homeostasis of Eye Growth and the Question of Myopia. Neuron 2012, 74, 207, 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.018.

- Qiuzhi Ji; Young-Sik Yoo; Hira Alam; Geunyoung Yoon; Through-focus optical characteristics of monofocal and bifocal soft contact lenses across the peripheral visual field. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 2018, 38, 326-336, 10.1111/opo.12452.

- Antonio Medina; The progression of corrected myopia. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2015, 253, 1273-1277, 10.1007/s00417-015-2991-5.

- Daniel Adler; Michel Millodot; The possible effect of undercorrection on myopic progression in children. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 2006, 89, 315-321, 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2006.00055.x.

- Kahmeng Chung; Norhani Mohidin; Daniel J. O’Leary; Undercorrection of myopia enhances rather than inhibits myopia progression.. Vision Research 2002, 42, 2555-2559, 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00258-4.

- Si Yuan Li; Shi-Ming Li; Yue Hua Zhou; Luo Ru Liu; He Li; Meng Tian Kang; Si-Yan Zhan; Ningli Wang; Michel Millodot; Effect of undercorrection on myopia progression in 12-year-old children. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2015, 253, 1363-1368, 10.1007/s00417-015-3053-8.

- Editha Ong; Kenneth Grice; Richard Held; Frank Thorn; Jane Gwiazda; Effects of Spectacle Intervention on the Progression of Myopia in Children. Optometry and Vision Science 1999, 76, 363-369, 10.1097/00006324-199906000-00015.

- Yun-Yun Sun; Shi-Ming Li; Si-Yuan Li; Meng-Tian Kang; Luo-Ru Liu; Bo Meng; Feng-Ju Zhang; Michel Millodot; Ningli Wang; Effect of uncorrection versus full correction on myopia progression in 12-year-old children. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2016, 255, 189-195, 10.1007/s00417-016-3529-1.

- Balamurali Vasudevan; Christina Esposito; Cody Peterson; Cory Coronado; Kenneth J. Ciuffreda; Under-correction of human myopia – Is it myopigenic?: A retrospective analysis of clinical refraction data. Journal of Optometry 2014, 7, 147-152, 10.1016/j.optom.2013.12.007.

- John R Phillips; Monovision slows juvenile myopia progression unilaterally. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2005, 89, 1196-1200, 10.1136/bjo.2004.064212.

- Tokoro, T.; Kabe, S. Treatment of the myopia and the changes in optical components. Report II. Full- or under-correction of myopia by glasses.Nihon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi, 965,69, 140–144

- M. R. Angi; F. Forattini; C. Segalla; E. Mantovani; Myopia evolution in pre-school children after full optical correction. Strabismus 1996, 4, 145-157, 10.3109/09273979609055050.

- James S Wolffsohn; Pete S. Kollbaum; David Berntsen; David A. Atchison; Alexandra Benavente; Arthur Bradley; Hetal Buckhurst; Michael Collins; Takashi Fujikado; Takahiro Hiraoka; et al. IMI – Clinical Myopia Control Trials and Instrumentation Report. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 2019, 60, M132-M160, 10.1167/iovs.18-25955.

- Nicola S Logan; James Wolffsohn; Role of un‐correction, under‐correction and over‐correction of myopia as a strategy for slowing myopic progression. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 2019, 103, 133-137, 10.1111/cxo.12978.

- O Pärssinen; E Hemminki; A Klemetti; Effect of spectacle use and accommodation on myopic progression: final results of a three-year randomised clinical trial among schoolchildren.. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1989, 73, 547-551, 10.1136/bjo.73.7.547.

- Nana Yaa Koomson; Angela Ofeibea Amedo; Collins Opoku-Baah; Percy Boateng Ampeh; Emmanuel Ankamah; Kwaku Bonsu; Relationship between Reduced Accommodative Lag and Myopia Progression. Optometry and Vision Science 2016, 93, 683-691, 10.1097/opx.0000000000000867.

- Chen, Y.-H.; Clinical observation of the development of juvenile myopia wearing glasses with full correction and under-correction. International Journal of Ophthalmology 2014, 14, 1553-1554, .

- Hu G.-H.; Guo P.-M.; Effects of different degree correction of refractive error in young myopia patients. Guoji Yanke Zazhi (Int Eye Sci) 2012, 12, 2233-2234, .

- Sheela Evangeline Kumaran; Sudharsanam Manni Balasubramaniam; Divya Senthil Kumar; Krishna Kumar Ramani; Refractive Error and Vision-Related Quality of Life in South Indian Children. Optometry and Vision Science 2015, 92, 272-278, 10.1097/opx.0000000000000494.

- Jennifer Evans; Priya Morjaria; Christine Powell; Vision screening for correctable visual acuity deficits in school-age children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, 2018, CD005023, 10.1002/14651858.CD005023.pub3.

- Hans Strasburger; Michael Bach; Sven P. Heinrich; Blur Unblurred—A Mini Tutorial. i-Perception 2018, 9, 2041669518765850, 10.1177/2041669518765850.

- Ralf Blendowske; Unaided Visual Acuity and Blur. Optometry and Vision Science 2015, 92, e121-5, 10.1097/opx.0000000000000592.

- Kalpa Negiloni; Krishna Kumar Ramani; Rachapalle Reddi Sudhir; Do school classrooms meet the visual requirements of children and recommended vision standards?. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174983, 10.1371/journal.pone.0174983.