1. Introduction

While the evidence supporting the interaction between the human host and the microbiome increases, the identification of microbiome-related biomarkers and the understanding of the role of microbiota in drug metabolization are also the focus of intense research. However, whether genetic or related to microbiota, validation of biomarkers among adults does not necessarily imply its usefulness in children, as gene expression and microbial colonization vary during childhood. It is known that the microbiome is established mainly during the first year of life, although fluctuations in the ecosystem occur over time together with lifetime changes [8]. Beyond age and genetic factors, the microbiome is deeply influenced by geographical, dietary, and lifestyle-related factors [9]. Studies suggest that these factors may be especially relevant in shaping the microbiome during childhood [7,8]. Social determinants of health have a direct impact on undoubtfully critical factors for health, such as malnutrition, access to treated water, or health care. In comparison, their effect on microbiota composition and how much these changes may contribute to health and disease may seem trivial and has not been well established.

2. Social Determinants of Health and the Microbiome in Children

Social inequities, poverty, or racism have profound impacts on life expectancy [

3]. Defined by the World Health Organization as the “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age and the wide set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life” [

10], the so-called social determinants of health (SDOH) are known to have a powerful effect on health outcome [

11,

12,

13]. Disparities among children’s health and healthcare utilization along demographic lines such as race and income have long been documented as factors influencing children’s morbidity and mortality [

10]. Although SDOH influence health and well-being across individuals of all ages, in children and young people, physical, social, and emotional capabilities that develop early in life provide the basis for life course health and well-being [

14]. Emerging data demonstrate that exposure to violence, food scarcity, poverty, and lack of housing, as well as race, ethnicity, gender, education, and health literacy, are potent determinants and comorbid issues for many conditions [

13]. Recently, the human microbiome has been identified as a potentially modifiable determinant of health, which is highly determined itself by social and geographical conditions.

Although our understanding of the impact of the human microbiome on health is still in the early stages, current knowledge indicates that the interaction between microbiota and the host is strong. Around 10

13 microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa, accounting for a total mass of 0.2 kg [

15], inhabit our bodies and constitute the human microbiome. An overwhelming amount of data has underlined the influence of the first years of life to shape the microbiome–immune system interactions in recent years. Very early in life, the microbiome is first established by the colonization of microorganisms from the mother’s skin, genital tract microbiota, breast milk, and after the introduction of complementary feeding [

16,

17]. Factors related to the mode of delivery, antimicrobial exposure early in life, or breast-feeding duration have been shown to impact microbiota acquisition [

8,

16]. Furthermore, it is known that these factors condition variations in gut microbiota that are associated with an increased risk of suffering from allergic diseases, asthma, celiac disease, or inflammatory bowel disease [

17,

18]. Geographic location and ethnicity also determine variability in the ecosystem [

19], together with well-known dietary and lifestyle-related factors [

17].

These environmental factors are deeply related to socio-economic conditions, including dietary restrictions, hygiene habits, housing conditions, and access to treated water or health care. Dietary habit modifications in the course of migration, for example, are key in shaping the gut microbiota. An ecosystem enriched in microorganisms specialized in degrading fibers, characteristic of children living in limited-resource settings, can be an adaptation to enhance energy obtention from the diet but could turn deleterious in the presence of a westernized diet [

20].

The geographical variability of vaccine response is another compelling example of the critical implications of host–microbiome and environmental interactions [

21]. In low-income countries, the poorer immunization rates achieved by oral vaccines (cholera, poliovirus, and rotavirus) have been classically related to environmental, socio-economic, or nutritional conditions [

22]. However, it may also be explained by changes in the intestinal microbiota composition [

21]. In a kind of infinite loop, dietary factors have a clear impact on the microbiome. Still, changes in the microbiome can lead to behavioral adaptations, leading to a subsequent modification in dietary habits [

23]. Among other challenges in the field, causality is always questionable in most microbiome studies in humans. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), common comorbidities of which are functional gastrointestinal disorders [

24], is an excellent example of this bidirectionality. Manipulation of the gut microbiome could offer a promising treatment option for children with ASD. Recently, significant changes in serum neurotransmitters and an improvement in behavioral and gastrointestinal symptoms were observed during a fecal microbiota transplantation trial in children diagnosed with autism [

25]. Yet, the longitudinal follow-up would be essential for further understanding of the so-called “gut-brain” axis.

The fact that the gut microbiome in children living in resource-limited settings has remained underreported in microbiome research is another clear example of how social inequities impact health from the very primary step of knowledge generation. Nevertheless, consistent data illustrate how pathogenic species are often detected in higher abundance among malnourished children living in low-income settings [

19,

26]. While there is agreement that nutrition and gut microbiota are linked, particularly in vulnerable populations such as children, it is highly controversial to what extent the theoretically modifiable human microbiome is a potential therapeutic target. Fecal microbiota transplantation has shown efficacy in very limited settings (recurrent

Clostridioides difficile associated diarrhea). Still, studies addressing the role of microbiota modulation with probiotics, prebiotics, or dietary interventions in treating and recovering from infections or inflammatory diseases have raised controversial results [

27,

28,

29]. Although these treatments’ impact and therapeutic potential have not been well-established yet, the evidence supports the need to implement measures to prioritize food security worldwide. Making nutritional modifications in areas with limited resources is a challenge, but it is also a priority to improve health.

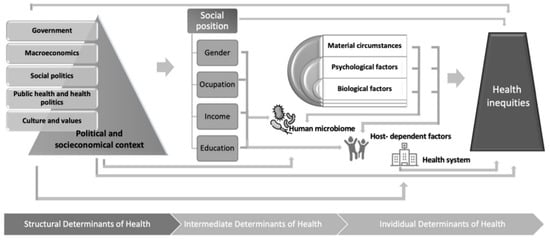

Untangling the crossroad of SDOH, the human microbiome, and human health is a formidable challenge (

Figure 1). Unfortunately, because the individual’s microbiota is fundamentally established during the first three years of life (from childbirth to the consolidation of the adult diet) [

17], the impact of socio-economic factors on the microbiome composition might be more significant in children compared to adults. An “unfavorable” microbiota may cause lasting damage [

20,

30]. Hence, the idea of the bidirectionality of social and host–microorganism interactions in health should be integrated into research and clinical perspectives from today. In addition to the possible therapeutic implications, some of them already mentioned, modification of the microbiota in childhood has been postulated to be key in the prevention of infections [

31], allergy [

32], asthma [

33], or even cancer in childhood [

34,

35,

36]. Therefore, the inclusion of children in clinical trials evaluating dietary modifications and their impact on various diseases and overall health should be prioritized.

Figure 1. Human microbiome at the crossroad between social determinants of health and personalized medicine.