Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Oncology

|

Neurosciences

Flavonoids are polyphenolic plant secondary metabolites with pleiotropic biological properties, including anti-cancer activities. These natural compounds have potential utility in glioblastoma (GBM), a malignant central nervous system tumor derived from astrocytes.

- glioblastoma

- glioma

- flavonoids

1. The Challenges of GBM Therapy and the Potential of Flavonoids

Glioblastoma (GBM) is an astrocyte-derived solid tumor of the brain or spinal cord that occurs at an overall rate of 3.19 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States. Its incidence varies notably between subpopulations, with males and older individuals at higher risk [1]. GBM is fatal, with median survival times under one year [2].

Currently, conventional medical and surgical interventions predominate in GBM therapy. Standard treatment regimens include (1) radiation therapy with concurrent temozolomide (TMZ) chemotherapy and (2) surgical tumor resection with radiation therapy [3][4]. Recent advances in these therapies have improved patient outcomes; the addition of TMZ, an alkylating agent, to standard radiation-only regimens after 2005 greatly increased survival rates [2]. Nevertheless, conventional interventions remain constrained by GBM’s malignant properties. Surgical methods, for instance, are hindered by widespread tumor invasion and metastasis, while drug and radiation resistance—particularly associated with glioma stem cells (GSCs)—pose challenges for chemo- and radiotherapy [5][6]. Intra- and intertumoral heterogeneity further complicates anti-GBM regimens [6]. Therefore, a need exists for alternative and supportive therapies with the potential to overcome these challenges.

Dietary natural compounds constitute promising candidates in this regard; they have wide-ranging biological properties, including anti-cancer effects [7][8][9][10][11]. Among these compounds, flavonoids—polyphenolic plant secondary metabolites—are of interest. Flavonoids exert anti-cancer effects through chemosensitization, metabolic modulation, metastatic inhibition, and apoptotic induction [12][13]. Based on these well-evidenced oncostatic activities, flavonoids have great potential in modulating GBM cell responses to anti-cancer drugs by overcoming their therapeutic resistance.

2. Flavonoids and Chemotherapeutics in GBM Therapy

2.1. Flavonoids

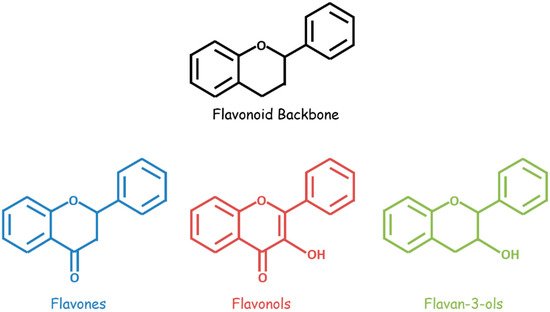

Bioactive flavonoids occur in fruits, vegetables, and other natural plant products and are unified by a three-ring structural backbone that includes two phenyl rings and one central heterocyclic ring. These compounds are classified based on structural differences—related primarily to the presence and positioning of substituents on the heterocycle (Figure 1). A variety of flavonoids, including flavan-3-ols, flavones, isoflavones, flavonols, flavonol glycosides, and flavonolignans, demonstrate anti-GBM effects combined with chemotherapeutic drugs in vitro and/or in vivo (Table 1).

Figure 1. General structures of flavonoids (black), flavones (blue), flavonols (red), and flavan-3-ols (green).

Table 1. Classes and sources of eight flavonoids that synergize with chemotherapeutics to inhibit GBM.

| Flavonoid | Class | Canonical or Common Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGCG | Flavan-3-ol | Green and white tea | [14] |

| Chrysin | Flavone | Passionflower (Passiflora) | [15] |

| Hispidulin | Flavone | Gumweed (Grindelia argentina) | [16] |

| Formononetin | Isoflavone | Red clover (Trifolium pratense) | [17] |

| Quercetin | Flavonol | Oak (Quercus) | [18] |

| Icariin | Flavonol Glycoside | Horny goat weed (Epimedium) | [19] |

| Rutin | Flavonol Glycoside | Rue (Ruta graveolens) | [20] |

| Silibinin | Flavonolignan | Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) | [21] |

2.2. Chemotherapeutics

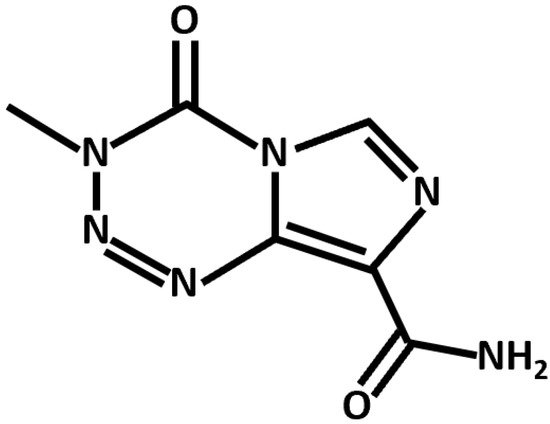

Conventional chemotherapeutics leverage diverse mechanistic pathways to exert their anti-cancer effects. TMZ, the canonical anti-GBM drug, is an alkylating agent that induces apoptotic cell death through the p53-dependent and O6-methylguanine-based activation of the Fas/caspase 8 pathway (Figure 2) [22]. In addition, several noncanonical and repurposed drugs hold promise in synergistic GBM therapy (Table 2).

Figure 2. Chemical structure of TMZ, an alkylating agent and anti-GBM chemotherapeutic.

Table 2. Classes and functions of chemotherapeutic drugs that have synergistic anti-GBM potential in combination with flavonoids.

| Chemotherapeutic | Class | Primary Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATO | Arsenic compounds | Multimodal | [23] |

| Chloroquine | Anti-malarials | Autophagy inhibitor | [24] |

| Cisplatin | Platinum compounds | Alkylating agent | [25] |

| Etoposide | Natural product derivatives | Topoisomerase II inhibitor | [26] |

| Sodium Butyrate (NaB) | Short-chain fatty acids | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | [27] |

| TMZ | Purine analogs | Alkylating agent | [22] |

3. Mechanisms of GBM and Synergistic Flavonoid-Chemotherapeutic Effects

3.1. Mechanisms of GBM

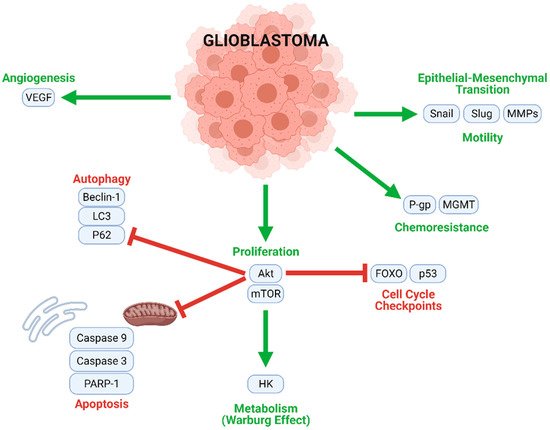

GBM tumorigenesis, progression, and metastasis are driven by numerous interconnected signaling mechanisms (Figure 3). Rapid cell proliferation, an essential process at all stages of GBM development, is mediated by the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), nuclear factor κappa of activated B cells (NF-κB), and other similar pathways. Uncontrolled proliferation of this nature is enabled by the inhibition of normal cell cycle controls (such as FOXO and p53), and the downregulation of key actors in autophagic (LC3, Beclin-1, and P62) and apoptotic (caspases) cell death. Moreover, a metabolic transition to aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) energetically sustains rapid GBM cell division. Angiogenic and neovascular processes—stimulated mainly by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling—ensure oxygen and nutrient transport to growing tumors. GBM cells may further develop chemoresistance; this often occurs through O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT), which confers resistance to alkylating agents and/or P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which enhances drug efflux from the cells. Finally, Snail, Slug, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) contribute to the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), which causes GBM cells to develop migratory and invasive phenotypes.

Figure 3. Multiple intracellular processes contribute to GBM tumorigenesis and progression. Mechanisms contributing to proliferation, chemoresistance, metabolism, angiogenesis, and motility (migration) are upregulated in GBM cells, while cell cycle checkpoints, autophagy, and apoptosis are inhibited.

3.2. Flavonoids and TMZ

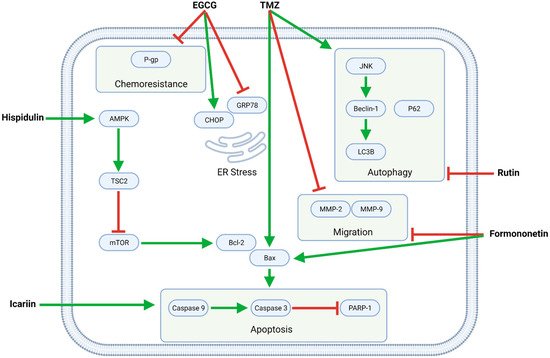

Several flavonoids—EGCG, formononetin, hispidulin, icariin, and rutin—synergize with TMZ in modulating intracellular pathways related to proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, migration, and chemoresistance (Figure 4, Table 3).

Figure 4. The flavonoids EGCG, formononetin, hispidulin, icariin, and rutin exert pleiotropic anti-GBM effects combined with TMZ. Formononetin, hispidulin, and icariin synergistically enhance TMZ-mediated apoptosis by increasing the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and activating caspases; formononetin additionally potentiates TMZ’s anti-migratory effects. Moreover, EGCG downregulates P-gp, thereby increasing the sensitivity of (otherwise resistant) GBM cells to TMZ. Finally, rutin inhibits TMZ-induced autophagy and, as such, promotes apoptotic cell death.

Table 3. Mechanistic anti-GBM effects of flavonoid-TMZ combinations, as demonstrated in vitro and in vivo.

| Effect | Cell Line | Flavonoid | Flavonoid Conc. | TMZ Conc. | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increases survival time | Intracranial U87 xenografts, nude mice | EGCG | 50 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | [28] |

| Intracranial U251 xenografts, nude mice | EGCG | 50 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | [28] | |

| Decreases tumor volume | Subcutaneous U87 xenografts, BALB/c mice | Rutin | 20 mg/kg | 55 mg/kg | [29] |

| Decreases tumor weight | Subcutaneous U87 xenografts, BALB/c mice | Rutin | 20 mg/kg | 55 mg/kg | [29] |

| Intracranial U87 xenografts, BALB/c mice | Rutin | 20 mg/kg | 55 mg/kg | [29] | |

| Increases cell death/dec viability | C6 | Marcela Extract | 10, 20, 50 µg/mL | 200 µM | [30] |

| U87 | Marcela Extract | 10, 20, 50 µg/mL | 200 µM | [30] | |

| U251 | Marcela Extract | 50 µg/mL | 100 µM | [30] | |

| U87MG | Rutin | 50, 100, 200 µM | 63, 250, 500, 1000 µM | [29] | |

| D54MG | Rutin | 50, 100, 200 µM | 63, 125, 250, 500, 1000 µM | [29] | |

| U251MG | Rutin | 50, 100, 200 µM | 63, 125, 250, 500, 1000 µM | [29] | |

| LN229 | Silibinin | 50 µM | 10, 25, 50 µM | [31] | |

| TR-LN229 | Silibinin | 50 µM | 10, 25, 50 µM | [31] | |

| U87 | Silibinin | 50 µM | 25, 50 µM | [31] | |

| U87MG | Icariin | 10 µM | 200 µM | [32] | |

| SHG44 | Hispidulin | 40 µM | 100 µM | [33] | |

| U87 GSLC | EGCG | 100 µM | 100 µM | [34] | |

| U251 | EGCG | 10, 20 µM | 20, 40 µM | [28] | |

| C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80, 160, 320 µM | 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000 µM | [35][36] | |

| GBM8901 | PWE | 50 µg/mL | 100, 150, 200 µM | [37] | |

| Decreases colony formation | U87 | Marcela Extract | 10, 20, 50 µg/mL | 50 µM | [30] |

| Decreases proliferation | U87MG | Icariin | 10 µM | 200 µM | [32] |

| Increases apoptosis | U87MG | Icariin | 10 µM | 200 µM | [32] |

| SHG44 | Hispidulin | 40 µM | 100 µM | [33] | |

| U251 | EGCG | 20 µM | 100 µM | [28] | |

| C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80 µM | 125, 500 µM | [35][36] | |

| Upregulates (c-)caspase 3 (protein) | C6 | Marcela Extract | 50 µg/mL | 200 µM | [30] |

| U251 | Marcela Extract | 50 µg/mL | 100 µM | [30] | |

| U87 | Rutin | 100, 200 µM | 500 µM | [29] | |

| U87MG | Icariin | 10 µM | 200 µM | [32] | |

| C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80 µM | 125, 500 µM | [35][36] | |

| Upregulates (c-)caspase 9 (protein) | C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80 µM | 125, 500 µM | [35][36] |

| Upregulates (c-)PARP (protein) | U87MG | Icariin | 10 µM | 200 µM | [32] |

| Upregulates Bax (protein) | C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80 µM | 125, 500 µM | [35][36] |

| Downregulates Bcl-2 (protein) | SHG44 | Hispidulin | 40 µM | 100 µM | [33] |

| C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80 µM | 125, 500 µM | [35][36] | |

| Downregulates Survivin (protein) | LN229 | Silibinin | 50 µM | 50 µM | [31] |

| Downregulates LC3-II (protein) | U87 | Rutin | 100, 200 µM | 500 µM | [29] |

| GBM8901 | PWE | 50 µg/mL | 100 µM | [37] | |

| Downregulates Beclin-1 (protein) | GBM8901 | PWE | 50 µg/mL | 100 µM | [37] |

| Downregulates P62 (protein) | GBM8901 | PWE | 50 µg/mL | 100 µM | [37] |

| Downregulates (p-)JNK (protein) | U87 | Rutin | 100, 200 µM | 500 µM | [29] |

| Upregulates CHOP (protein) | Intracranial U87 xenografts, nude mice | EGCG | 50 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | [28] |

| Intracranial U251 xenografts, nude mice | EGCG | 50 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | [28] | |

| Downregulates GRP78 (protein) | Intracranial U87 xenografts, nude mice | EGCG | 50 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | [28] |

| Intracranial U251 xenografts, nude mice | EGCG | 50 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | [28] | |

| Upregulates (p-)AMPK (protein) | SHG44 | Hispidulin | 40 µM | 100 µM | [33] |

| Downregulates (p-)mTOR (protein) | SHG44 | Hispidulin | 40 µM | 100 µM | [33] |

| Decreases cell migration | U87MG | Icariin | 10 µM | 200 µM | [32] |

| C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80 µM | 125, 500 µM | [35][36] | |

| Downregulates MMP-2 (protein) | C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80 µM | 125, 500 µM | [35][36] |

| Downregulates MMP-9 (protein) | C6 | Formononetin | 40, 80 µM | 125, 500 µM | [35][36] |

| Decreases cell invasion | U87MG | Icariin | 10 µM | 200 µM | [32] |

| Increases G2/M phase arrest | SHG44 | Hispidulin | 40 µM | 100 µM | [33] |

| Downregulates NF-κB | U87MG | Icariin | 10 µM | 200 µM | [32] |

| Downregulates P-gp | U87 GSLC | EGCG | 100 µM | 100 µM | [34] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom11121841

References

- Tamimi, A.F.; Juweid, M. Epidemiology and Outcome of Glioblastoma. In Glioblastoma; De Vleeschouwer, S., Ed.; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2017.

- Johnson, D.R.; O’Neill, B.P. Glioblastoma survival in the United States before and during the temozolomide era. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012, 107, 359–364.

- Becker, K.P.; Yu, J. Status quo--standard-of-care medical and radiation therapy for glioblastoma. Cancer J. 2012, 18, 12–19.

- Nishikawa, R. Standard therapy for glioblastoma—A review of where we are. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2010, 50, 713–719.

- Lara-Velazquez, M.; Al-Kharboosh, R.; Jeanneret, S.; Vazquez-Ramos, C.; Mahato, D.; Tavanaiepour, D.; Rahmathulla, G.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A. Advances in Brain Tumor Surgery for Glioblastoma in Adults. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 166.

- Noch, E.K.; Ramakrishna, R.; Magge, R. Challenges in the Treatment of Glioblastoma: Multisystem Mechanisms of Therapeutic Resistance. World Neurosurg. 2018, 116, 505–517.

- Zhai, K.; Brockmuller, A.; Kubatka, P.; Shakibaei, M.; Busselberg, D. Curcumin’s Beneficial Effects on Neuroblastoma: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Potential Solutions. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1469.

- Koklesova, L.; Liskova, A.; Samec, M.; Zhai, K.; Abotaleb, M.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Brockmueller, A.; Shakibaei, M.; Biringer, K.; Bugos, O.; et al. Carotenoids in Cancer Metastasis-Status Quo and Outlook. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1653.

- Brockmueller, A.; Sameri, S.; Liskova, A.; Zhai, K.; Varghese, E.; Samuel, S.M.; Büsselberg, D.; Kubatka, P.; Shakibaei, M. Resveratrol’s Anti-Cancer Effects through the Modulation of Tumor Glucose Metabolism. Cancers 2021, 13, 188.

- Liskova, A.; Samec, M.; Koklesova, L.; Samuel, S.M.; Zhai, K.; Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Abotaleb, M.; Nosal, V.; Kajo, K.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; et al. Flavonoids against the SARS-CoV-2 induced inflammatory storm. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111430.

- Koklesova, L.; Liskova, A.; Samec, M.; Zhai, K.; Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Bugos, O.; Šudomová, M.; Biringer, K.; Pec, M.; Adamkov, M.; et al. Protective Effects of Flavonoids Against Mitochondriopathies and Associated Pathologies: Focus on the Predictive Approach and Personalized Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8649.

- Liskova, A.; Samec, M.; Koklesova, L.; Brockmueller, A.; Zhai, K.; Abdellatif, B.; Siddiqui, M.; Biringer, K.; Kudela, E.; Pec, M.; et al. Flavonoids as an effective sensitizer for anti-cancer therapy: Insights into multi-faceted mechanisms and applicability towards individualized patient profiles. EPMA J. 2021, 12, 155–176.

- Samec, M.; Liskova, A.; Koklesova, L.; Mersakova, S.; Strnadel, J.; Kajo, K.; Pec, M.; Zhai, K.; Smejkal, K.; Mirzaei, S.; et al. Flavonoids Targeting HIF-1: Implications on Cancer Metabolism. Cancers 2021, 13, 130.

- Singh, B.N.; Shankar, S.; Srivastava, R.K. Green tea catechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): Mechanisms, perspectives and clinical applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 1807–1821.

- Mani, R.; Natesan, V. Chrysin: Sources, beneficial pharmacological activities, and molecular mechanism of action. Phytochemistry 2018, 145, 187–196.

- Patel, K.; Patel, D.K. Medicinal importance, pharmacological activities, and analytical aspects of hispidulin: A concise report. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 360–366.

- Tay, K.C.; Tan, L.T.; Chan, C.K.; Hong, S.L.; Chan, K.G.; Yap, W.H.; Pusparajah, P.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H. Formononetin: A Review of Its Anticancer Potentials and Mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 820.

- Kelly, G.S. Quercetin. Altern. Med. Rev. 2011, 16, 172–194.

- Tan, H.L.; Chan, K.G.; Pusparajah, P.; Saokaew, S.; Duangjai, A.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H. Anti-Cancer Properties of the Naturally Occurring Aphrodisiacs: Icariin and Its Derivatives. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 191.

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The Pharmacological Potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 149–164.

- Deep, G.; Agarwal, R. Antimetastatic efficacy of silibinin: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential against cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010, 29, 447–463.

- Roos, W.P.; Batista, L.F.; Naumann, S.C.; Wick, W.; Weller, M.; Menck, C.F.; Kaina, B. Apoptosis in malignant glioma cells triggered by the temozolomide-induced DNA lesion O6-methylguanine. Oncogene 2007, 26, 186–197.

- Hoonjan, M.; Jadhav, V.; Bhatt, P. Arsenic trioxide: Insights into its evolution to an anticancer agent. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 23, 313–329.

- Kim, E.L.; Wustenberg, R.; Rubsam, A.; Schmitz-Salue, C.; Warnecke, G.; Bucker, E.M.; Pettkus, N.; Speidel, D.; Rohde, V.; Schulz-Schaeffer, W.; et al. Chloroquine activates the p53 pathway and induces apoptosis in human glioma cells. Neuro-Oncology 2010, 12, 389–400.

- Park, C.-M.; Park, M.-J.; Kwak, H.-J.; Moon, S.-I.; Yoo, D.-H.; Lee, H.-C.; Park, I.-C.; Rhee, C.H.; Hong, S.-I. Induction of p53-mediated apoptosis and recovery of chemosensitivity through p53 transduction in human glioblastoma cells by cisplatin. Int. J. Oncol. 2006, 28, 119–125.

- Sawada, M.; Nakashima, S.; Banno, Y.; Yamakawa, H.; Hayashi, K.; Takenaka, K.; Nishimura, Y.; Sakai, N.; Nozawa, Y. Ordering of ceramide formation, caspase activation, and Bax/Bcl-2 expression during etoposide-induced apoptosis in C6 glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2000, 7, 761–772.

- Engelhard, H.H.; Duncan, H.A.; Kim, S.; Criswell, P.S.; Van Eldik, L. Therapeutic effects of sodium butyrate on glioma cells in vitro and in the rat C6 glioma model. Neurosurgery 2001, 48, 616–624, discussion 624–615.

- Chen, T.C.; Wang, W.; Golden, E.B.; Thomas, S.; Sivakumar, W.; Hofman, F.M.; Louie, S.G.; Schonthal, A.H. Green tea epigallocatechin gallate enhances therapeutic efficacy of temozolomide in orthotopic mouse glioblastoma models. Cancer Lett. 2011, 302, 100–108.

- Zhang, P.; Sun, S.; Li, N.; Ho, A.S.W.; Kiang, K.M.Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.S.; Poon, M.W.; Lee, D.; Pu, J.K.S.; et al. Rutin increases the cytotoxicity of temozolomide in glioblastoma via autophagy inhibition. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2017, 132, 393–400.

- Souza, P.O.; Bianchi, S.E.; Figueiro, F.; Heimfarth, L.; Moresco, K.S.; Goncalves, R.M.; Hoppe, J.B.; Klein, C.P.; Salbego, C.G.; Gelain, D.P.; et al. Anticancer activity of flavonoids isolated from Achyrocline satureioides in gliomas cell lines. Toxicol. In Vitro 2018, 51, 23–33.

- Elhag, R.; Mazzio, E.A.; Soliman, K.F.A. The Effect of Silibinin in Enhancing Toxicity of Temozolomide and Etoposide in p53 and PTEN-mutated Resistant Glioma Cell Lines. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 1263–1269.

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Guo, M. Synergistic Anti-Cancer Effects of Icariin and Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 71, 1379–1385.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; He, X.; Fei, Z. Hispidulin enhances the anti-tumor effects of temozolomide in glioblastoma by activating AMPK. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 71, 701–706.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.X.; Ma, J.W.; Li, H.Y.; Ye, J.C.; Xie, S.M.; Du, B.; Zhong, X.Y. EGCG inhibits properties of glioma stem-like cells and synergizes with temozolomide through downregulation of P-glycoprotein inhibition. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2015, 121, 41–52.

- Zhang, X.; Ni, Q.; Wang, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, Y. Synergistic Anticancer Effects of Formononetin and Temozolomide on Glioma C6 Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 41, 1194–1202.

- Ni, Q.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fan, H.; Li, Y. In vitro and in vivo Study on Glioma Treatment Enhancement by Combining Temozolomide with Calycosin and Formononetin. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 242, 111699.

- Liao, C.L.; Chen, C.M.; Chang, Y.Z.; Liu, G.Y.; Hung, H.C.; Hsieh, T.Y.; Lin, C.L. Pine (Pinus morrisonicola Hayata) needle extracts sensitize GBM8901 human glioblastoma cells to temozolomide by downregulating autophagy and O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase expression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 10458–10467.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!