The inflow of toxic materials to the water environment affects water parameters and leads to alterations in the fish hematological profile [

33,

34]. Toxic exposure can adversely affect the blood oxygen carrying capacity and the blood electrolyte balance, especially ammonia exposure can induce the accumulation of ammonia in fish circulatory system. As ammonia has high affinity for blood hemoglobin, it displaces oxygen and influences some hematological properties [

35]. Hematological properties are significant indicators to assess fish health status after exposed to different environmental stresses and chemical toxicity [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Ammonia enters the fish circulatory system and causes metabolic disturbances and fatal responses, such as oxidative stress, immune response and genetic expression [

40]. Exposure to ammonia also affects the fish circulatory system, particularly hematological indexes such as red blood cell count (RBC), hematocrit (Ht) and hemoglobin (Hb) [

32]. In general, exposure to toxic substances decreases hematological properties like RBC, Ht and Hb owing to the hemolysis and red blood cells destruction and may cause anemia [

41]. Praveena et al. suggested that the decrease in RBC and the concentration of hemoglobin resulting from toxicity exposure might be attributed to the destructive effects of toxicity, but the decrease in the concentration of hemoglobin resulted in a potential impairment of tissue function because of the inadequate oxygen supply to the tissues [

42]. Gao et al. observed significant declines in Hb content, Ht and blood RBC counts after exposure to high concentrations of ammonia in

Takifugu rubripes, suggesting that the fish was anemic by exposure to ammonia [

40]. Hoseini et al. revealed that the increase in radicals exposed to ammonia could lead to attack on RBCs, leading to their destruction [

43]. Researches have revealed that the ammonia toxicity induces the inhibition of hematopoiesis by destroying the production sites of red blood cells [

44]. The onset of anemia symptoms may be due to destruction of red blood cells or injury to hematopoietic tissues after exposure to ammonia. Serum proteins are considered to be reliable indicators of fish immune status and health [

45]. David et al. attributed the decreased protein content in the toxically exposed fish to the disruption or collapse of cell functions and the concomitant impairment of protein synthetic mechanisms [

46]. Asthana et al. reported that high concentration of ammonia resulted in the deamination of proteins and increased the degradation of proteins [

47]. Ammonia exposure induced a reduction in hematological properties like RBC, Ht and Hb in fish, which is considered to account for the stress-induced decline in Hb content and Hb synthesis rate. Thus, it may exert a toxic effect by inducing disturbances in tissue oxygenation.

Ammonia absorbed in fish diffuses through cell membranes into the blood system and causes accumulation. Therefore, hematological parameters usually act as sensitive indicators to evaluate the toxicity of ammonia to fish [

48]. The effects of ammonia on fish hematological parameters are shown in

Table 1, regarding the route of exposure (freshwater, seawater, waterborne exposure). The decrease in hematological properties induced by ammonia exposure is manifested by disruption of RBC and alteration of the small or large red blood cell anemic state. Das et al. reported changes in blood characteristics (such as RBCs and hemoglobin) of

Cirrhinus mrigala after exposure to ammonia [

49]. This phenomenon causes tissue damage due to ammonia toxicity and hemodilution after hemolysis. Iheanacho et al. showed that changes in RBC content, hematocrit values and hemoglobin concentration reflected the fish defensive mechanisms against stress induced by exposure to environmental toxicity [

50]. Kim et al. revealed that the ammonia exposure greatly decreased the levels of hematocrit and hemoglobin in juvenile hybrid grouper [

48]. These authors considered that fish tissues might be under hypoxic conditions because of ammonia exposure and may result in the inhibition and depletion of hematopoietic potential under that condition.

The balance of glucose levels is maintained by balancing the production of glucose and the storage of glucose as glycogen [

51]. Glucose metabolism meets the energy requirements of the organs and tissues, which can mediate the ammonia response. Zhao et al. reported a significant increase in glucose in juvenile yellow catfish,

Pelteobagrus fulvidraco, exposed to ammonia [

52]. Long-term exposure to ammonia results in a dramatic elevation of blood glucose in

Litopenaeus vannamei owing to the impaired glucose metabolism in the liver [

53]. Lower glucose levels were critical for reducing tissue injuries and maintaining low levels of gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in stressful conditions [

32]. Changes in glucose levels in fish caused by ammonia exposure were attributed to stress responses or disturbances in homeostasis.

Enzyme plasma components including aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) are recognized as credible and sensitive biological indicators for evaluating damages to the liver and other fish organs following environmental stress [

54]. Plasma ALT and AST levels play important roles in indicating hepatopancreatic functions and injuries, and can be used as sensitive indicators of hepatocyte integrity [

55]. Zhao et al. revealed that AST and ALT levels were significantly increased in juvenile yellow catfish,

Pelteobagrus fulvidraco, exposed to ammonia, which may be due to damage to cell membranes and liver [

52]. Hoseini et al. recorded significant increases in ALT, AST and ALP of

Cyprinus carpio following ammonia exposure, which may be due to damage to cell membranes [

43]. Zhang et al. reported that ALP levels were significantly increased in

Megalobrama amblycephala exposed to ammonia [

11]. ALP is an important indicator reflecting liver damage, so the upward trend in ALP in

Megalobrama amblycephala is thought to be attributed to liver damage and stress caused by ammonia exposure. Peyghan et al. reported that ammonia exposure induced a remarkable increase in ALP in

Cyprinus carpio, indicating that hematological parameters were affected [

56].

4. Oxidative Stress

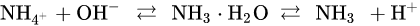

Oxidative stress is one of the toxicity mechanisms of ammonia nitrogen stress in aquatic animals [

7]. It has been shown that the increase in the concentration of ammonia nitrogen in aquaculture water can result in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in aquatic animals [

60]. ROS combines with unsaturated fatty acids and cholesterol on the cell membrane to produce lipid peroxidation, which leads to reduced mobility and greater cell membrane permeability. Disturbance of the distribution of proteins across the cell membrane leads to cell membrane dysfunction and apoptosis [

61,

62]. In order to counteract antioxidant stress and maintain the balance of the redox state of cells, antioxidant defense systems have evolved to function at different levels to avoid or repair this damage [

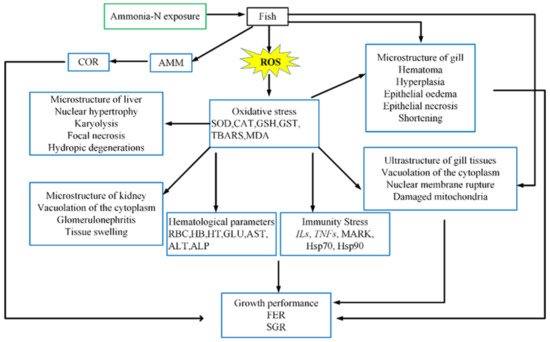

31]. The mechanism of oxidative stress in fish exposed to ammonia is shown in

Figure 2. Studies have reported that the activities of antioxidant enzymes can be elicited in low concentrations of pollutants and disrupted in high concentrations [

63,

64]. When physiological antioxidant system is unable to counteract the increased levels of stress-generated ROS, cellular oxidative stress occurs [

65].

Figure 2. Oxidative stress mechanisms in fish exposed to ammonia [

81]. H

2O

2: hydrogen peroxide; SOD: superoxide dismutase; CAT: catalase; GSH: glutathione; GST: Glutathione S-transferase; TBARS: Thiobarbituric reactive substances; MDA: malon dialdehyde; GPx: glutathione peroxide; GR: glutathione reductase; GSSG: glutathione; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate—Reprinted with permission from Ref. [

81]. 2021 Jun-Hwan Kim, Young-Bin Yu, Jae-Ho Choi.

Table 2 shows the responses of antioxidant enzymes in fish exposed to ammonia. The oxidative stress in fish exposed to ammonia stress is indicated by changes in the production of ROS in fish. One of the main defense strategies to reduce ROS production is by raising the activity of antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione (GSH) [

35,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. Antioxidant enzymes are widely present in tissues and are most abundant in hepatocytes [

70,

71]. Under stress, fish can protect the structure and function of cell membranes from peroxides by converting O

2− to H

2O

2 through SOD, GSH and CAT and by breaking down cytotoxic H

2O

2 into oxygen and water [

72].

Table 2. Antioxidant enzyme responses such as SOD, CAT and GST in fish exposed to ammonia.

| Exposure Route |

Exposure

Type |

Fish Specie |

Ammonia

Concentration |

Exposure Periods |

Response

Concentration |

Target Organs |

Response * |

Reference |

| SOD (Superoxide dismutase) |

| Sea water |

Waterborne

exposure |

Dicentrarchus labrax |

20 mg/L |

12, 48, 84, 180 h |

20 mg/L |

Blood |

× |

Sinha et al. [76] 2015 |

| Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × E. lanceolatus ♂ |

1, 2, 4, 8 mg/L |

1week, 2 wk |

4, 8 mg/L |

Liver, Gill |

+ |

Kim et al. [48] 2020 |

| Scophthalmus maximus |

5, 20, 40 mg/L |

24, 48, 96 h |

20, 40 mg/L |

Liver |

+ |

Jia et al. [98] 2020 |

| Chlamys farreri |

20 mg/L |

1, 12, 24 d |

20 mg/L |

Blood |

+ |

Wang et al. [85] 2012 |

| Takifugu rubripes |

5, 50, 100, 150 mg/L |

24 h |

50, 100, 150 mg/L |

Gill |

+ |

Gao et al. [40] 2021 |

| 48, 96 h |

50, 100, 150 mg/L |

Gill |

− |

| Freshwater |

Waterborne

exposure |

Carassius auratus |

10, 50 mg/L |

30 d |

10, 50 mg/L |

Liver |

− |

Qi et al. [9] 2017 |

| Megalobrama amblycephala |

5, 10, 15, 20 mg/L |

9 weeks |

20 mg/L |

Liver |

− |

Zhang et al. [11] 2019 |

| Cyprinus carpio |

106 mg/L |

24 h |

106 mg/L |

Blood |

× |

Hoseini et al. [43] 2019 |

| Oreochromis niloticus |

5, 10 mg/L |

70 days |

5, 10 mg/L |

Liver, Muscle |

+ |

Hegazi et al. [87] 2010 |

| CAT (Catalase) |

| Sea water |

Waterborne

exposure |

Dicentrarchus labrax |

20 mg/L |

12, 48, 84, 180 h |

20 mg/L |

Blood |

+ |

Sinha et al. [76] 2015 |

| Scophthalmus maximus |

5, 20, 40 mg/L |

24, 48, 96 h |

20, 40 mg/L |

Liver |

+ |

Jia et al. [98] 2020 |

| Takifugu rubripes |

5, 50, 100, 150 mg/L |

24 h |

50, 100, 150 mg/L |

Gill |

+ |

Gao et al. [40] 2021 |

| 48, 96 h |

50, 100, 150 mg/L |

Gill |

− |

| Freshwater |

Waterborne

exposure |

Carassius auratus |

10, 50 mg/L |

30 days |

10, 50 mg/L |

Liver |

× |

Qi et al. [9] 2017 |

| Megalobrama amblycephala |

5, 10, 15, 20 mg/L |

9 weeks |

20 mg/L |

Liver |

− |

Zhang et al. [11] 2019 |

| Cyprinus carpio |

106 mg/L |

24 h |

106 mg/L |

Blood |

− |

Hoseini et al. [43] 2019 |

| Corbicula fluminea |

10, 25 mg/L |

24, 48 h |

10 mg/L |

Digestive gland |

+ |

Zhang et al. [84] 2020 |

| 10, 25 mg/L |

24, 48 h |

10 mg/L |

Gill |

× |

| 10, 25 mg/L |

24, 48 h |

25 mg/L |

Digestive gland |

− |

| 10, 25 mg/L |

24, 48 h |

25 mg/L |

Gill |

+ |

| GST (Glutathione-S-transferase) |

| Sea water |

Waterborne

exposure |

Dicentrarchus labrax |

20 mg/L |

12, 48, 84, 180 h |

20 mg/L |

Blood |

+ |

Sinha et al. [76] 2015 |

| Takifugu rubripes |

5, 50, 100, 150 mg/L |

24 h |

50, 100, 150 mg/L |

Gill |

+ |

Gao et al. [40] 2021 |

| 48, 96 h |

50, 100, 150 mg/L |

Gill |

− |

| Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × E. lanceolatus ♂ |

1, 2, 4, 8 mg/L |

1 week |

4, 8 mg/L |

Liver, Gill |

+ |

Kim et al. [48] 2020 |

| Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × E. lanceolatus ♂ |

1, 2, 4, 8 mg/L |

2 weeks |

4, 8 mg/L |

Liver, Gill |

− |

| Freshwater |

Waterborne

exposure |

Carassius auratus |

10, 50 mg/L |

30 days |

10, 50 mg/L |

Liver |

× |

Qi et al. [9] 2017 |

| Paralichthys orbignyanus |

5, 10 mg/L |

70 days |

5, 10 mg/L |

Liver, Muscle |

+ |

Hoseini et al. [43] 2019 |

| Cyprinus carpio L. |

10, 20, 30 mg/L |

6, 24, 48 h |

30 mg/L |

Liver |

+ |

Li et al. [10] 2019 |

| 10, 20, 30 mg/L |

6, 24, 48 h |

10, 20, 30 mg/L |

Gill |

+ |

SOD is first defense against antioxidant stress [

73]. As a primary defense mechanism against antioxidant stress, SOD transforms superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2). SOD activity in ammonia-exposed fish is usually increased due to defense mechanisms against ROS production [

74]. Changes in SOD concentration appear to be associated with differences ammonia tolerance of fish. The SOD activity of rainbow trout, carp, goldfish and

Dicentrarchus labrax did not change significantly under ammonia stress [

75,

76]. SOD activity decreased significantly in

Carassius auratus and

Litopenaeus vannamei [

9,

77]. While in

Takifugu obscurus and

Pelteobagrus vachelli, SOD activity increased significantly [

78,

79]. However, excessive accumulation of free radicals inhibits antioxidant enzyme capacity to scavenge ROS, and a significant downward trend in SOD activity is observed after a remarkable increase in SOD activity. Kim et al. found that SOD activity in the liver and gills significantly increased when juvenile hybrid grouper exposure to ammonia. However, SOD activity in the gills had a downward trend when fish was subjected to high levels of ammonia. [

48]. Sun et al. revealed that when bighead carps were exposed to high concentrations of ammonia, the SOD activity of bighead carp,

Hypophthalmythys nobilis, larvae first increased and then decreased [

80]. The SOD activity may be stimulated in response to excessive ROS production, but then SOD activity declines because they are unable to perform under higher ammonia concentrations.

Ammonia exposure also leads to reduction in antioxidant enzymes as the energy expended in response to antioxidant stress. CAT is the major antioxidant enzyme to eliminate H

2O

2, a by-product of SOD, thus reducing its toxic effects [

35,

69,

82]. Xue et al. showed that ammonia exposure can depress normal ROS-mediated oxidative processes and reported a reduction of CAT activity in

Cyprinus carpio following ammonia exposure [

83]. Zhang et al. reported that ammonia exposure decreases SOD and CAT in the digestive gland of

Corbicula fluminea after an initial increase. This phenomenon is thought to be caused by the inhibition of antioxidant enzymes, as the ROS generated in the tissues are not cleared immediately. The activity of CAT also declined with increasing the concentration of ammonia, which indicated the oxidative damage and stress [

84]. In addition, Wang et al. concluded that the short time increase in antioxidant enzyme activity with treatment was not sufficient to fully counteract stress-induced cellular damage [

85]. In normal conditions, ROS are quickly removed by the antioxidant defense system. However, stimulated by large amounts of ammonia, excess ROS were produced, disrupting the cell membrane, forming lipid peroxides and oxidized proteins, and the balance between oxidants and antioxidants was disrupted. The body’s detoxification function was severely inhibited.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) functions in the second stage of the fish detoxification metabolism by conjugating to xenobiotics and clearing them from the cells, and the activity of GST is usually triggered in fish exposed to environmental toxins [

69]. Thus, GST plays a key role in homeostasis and foreign body dissociation, protecting tissues from oxidative stress of toxicant exposure [

86]. Many scholars have reported that ammonia exposure affects GST activity in fish through the induction of oxidative stress [

10,

75,

87]. Maltez et al. suggested that GST activity in Brazilian flounder (

Paralichthys orbignyanus) increased as a result of ammonia exposure and that ROS increased by ammonia exposure stimulated antioxidant defense [

88]. Kim et al. reported that GST activity in juvenile hybrid grouper initially increased significantly and tended to decrease with higher ammonia exposure concentration and time [

48]. Li et al. also reported a significant upward trend and subsequent downward trend in GST activity in carp following exposure to acute ammonia gas [

10]. The decrease in GST after the initial increase may be caused by excessive ROS production, which is consistent with the changes observed in SOD activity.

Thiobarbituric reactive substances (TBARS) was used as a measure of lipid peroxidation [

89]. It is well known that oxidative stress is caused by lipid peroxidation, leading to loss of cellular function [

90]. TBARS is a sensitive indicator for estimating lipid peroxidation as its products are produced by peroxidation of membrane lipids [

91]. Li et al. reported a gradual rise in brain TBARS levels in

Pelteobagrus fulvidraco exposed to high ammonia. They suggested that elevated brain TBARS levels could be an essential factor in the pathogenesis of ammonia toxicity in fish exposed to high concentrations of ammonia [

92]. Almroth et al. suggested that lipid peroxidation in fish occurs during oxidative stress from environmental toxicants [

93]. Aldehydes and ketones scan to crosslink with nucleophilic moieties of proteins, nucleic acids and aminophospholipids, and greater levels of TBARS result in increased cytotoxicity and accelerated cell and tissue damage [

94]. In particular, as fish contain many highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFA), TBARS can be used as a biomarker of oxidative stress [

95].

Excessive ROS production induces oxidative damage when fish were exposed to toxic substances, such as ammonia nitrogen. Excess ROS may damage cell membranes, form lipid peroxides and oxidize proteins [

33]. Usually, MDA is used as a biomarker of lipid peroxidation because it is an important product of membrane lipid peroxidation following free radical attack on biological membranes [

96,

97]. The changes of MDA content can indirectly reflect the level of disruption of biofilm system. Li et al. found no significant changes in the MDA content of

Cyprinus carpio L. during exposure to 10 mg/L ammonia water. However, after 48 h of exposure to 30 mg/L ammonia, MDA levels increased significantly [

10]. Xue et al. found that MDA levels had an upward trend when

Cyprinus carpio exposed to ammonia [

83]. The glutathione redox system could be triggered by ammonia stress. However, the antioxidant reaction is not sufficient to prevent oxidative damage caused by increased ammonia concentration. Ammonia exposure has toxic effects on fish through the induction of oxidative stress and ROS production, and antioxidant enzymes in fish such as SOD, CAT, GST, TBARS and MDA are the main indicators to reflect oxidative stress caused by ammonia.