Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Business, Finance

CFO compensation describes the remuneration of CFOs, which can be short-term and long-term oriented, cash based and non-cash based, and fixed or variable. The design of CFO compensation is crucial to aligning the interests of the CFO with the financial and non-financial interests of other stakeholders, making it an important corporate governance tool.

- corporate sustainability

- CFO compensation

1. Corporate Sustainability and CFO Compensation

Over the last years, a variety of different CS definitions have emerged. Some of these definitions understand CS as a mainly ecological concern [1] or as the firm’s social responsibility [2]. Others classify CS as the organizational concern about the natural and social environment, including corporate economic activities [3][4]. As there is no universal definition of CS, we rely on the definition by Berger et al. (2007). They describe CS as “the integration of social, environmental, and economic concerns into an organization’s culture, decision-making strategy, and operations” [5] (p. 133). Thereby, it is vital to CS that its activities go beyond legal requirements.

As CS is generally non-financial, it is hard to measure the outcomes of its activities, which in turn hinders its successful implementation. Also, investments into CS take time to show effect, which further increases the uncertainty of the outcome. Due to this time lag, investments into CS are considered riskier than other possible investment options [6][7][8]. Still, two different theoretical perspectives are explaining why CFOs engage in CS.

The first theory is the stakeholder-agent theory by Hill and Jones (1992) [9]. It gives two possible reasons for CFOs to invest in CS. First of all, executives (in our case, the CFO) and the shareholders may have differing interests. Due to executives having an information advantage compared to the shareholders, also called information asymmetries, the shareholders cannot ensure that executives act in their best interest. Executives could have contrary interests and put these above the shareholders’ interests, eventually leading to moral hazard. Moreover, the stakeholder-agent theory describes executives as agents of other stakeholder groups, including non-shareholders or non-controlling stakeholders. Thereby, executives are the only group of stakeholders that has direct control over the firm’s decision-making process. Therefore, as executives enter a contractual relationship with all stakeholders, they must make strategic decisions and allocate resources in the best interest of all stakeholders [9]. The stakeholders’ interests can relate to the economic, environmental, and social aspects of the firm’s performance [10][11]. To ensure that these interests are included in the context of strategic decision-making and resource allocation, the executives’ interests need to be aligned with the stakeholders’ interests [9][12]. This alignment of interests can be achieved by using an incentive-compatible management compensation system that includes sustainability aspects by the stakeholders [13]. Consequently, by linking the CFO compensation with the company’s performance, CFOs might be more encouraged to invest in CS to maximize their wealth and the firm’s performance simultaneously [14].

The second theory relevant in the examination of CFO compensation and CS refers to the institutional theory as proposed by Scott (2005) [15]. According to this theoretical lens, corporate legitimacy gives several economic and non-economic advantages like a lower risk of incurring legal or social sanctions and better access to resources [16]. To seize these advantages, firms need to protect or enhance their legitimacy, which is possible by meeting the expectations of institutions and stakeholders [15]. These economic and non-economic advantages might then improve the firms’ long-term financial performance [17]. However, legitimacy requires a long time to develop since building relationships with stakeholders and society takes time. Furthermore, additional time is needed to identify their expectations and to respond to those stakeholder needs and the norms of society [18]. Therefore, conditioning CFO compensation on the firm’s future financial performance might encourage the CFO to take actions that improve the relationships with stakeholders and society, including CS activities.

2. Classification of CFO Compensation Components and Hypotheses Development

CFO compensation at German firms can be split into three main compensation components: fixed, variable short-term, and long-term compensation. In Germany, firms pay the largest portion of executive compensation as fixed compensation [16]. Fixed compensation usually includes the annual base salary of the CFO and fringe benefits. Several studies are examining whether there is a positive [19] or a negative [20] relationship between CEO fixed compensation and CS. For CFO compensation, empirical evidence in connection with CS is still missing. After Gray and Cannella (1997), with fixed compensation, executives should be able to avoid damage from uncontrollable factors like market or industry shocks [19]. Furthermore, according to Hossain and Monroe (2015), fixed compensation is not significantly affected by short- or long-term performances [21]. Also, there are no prior studies to draw on further considerations.

Variable compensation can be divided into short-term and long-term compensation. Short-term compensation usually rewards executives once a year according to the degree to which the CFO has achieved specific predetermined targets successfully. Short-term compensation is focused on short-term benefits, which are generally in accordance with the firm’s growth. This bonus is often paid out in cash or stock and is based on individual, group, or corporate performance [22]. As variable short-term compensation focuses on short-term financial objectives, the CFO could divert resources from CS [23]. Also, CS strategies require an engagement of several years to take effect and only return benefits after a rather long time period [6]. Therefore, investing in CS projects might harm the short-term performance of a firm because the resources of a firm could be invested in different areas [24].

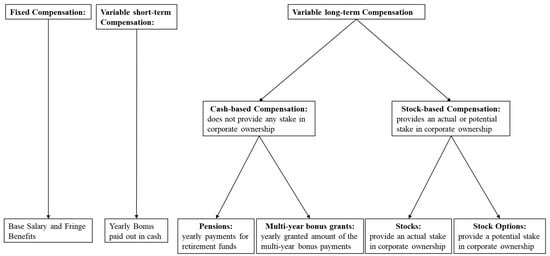

Most firms reward their executives with compensation packages that include one or more long-term components. These components are calculated on long-term performance for periods between 2 and 5 years [22]. Two main reasons for firms to provide long-term compensation to their executives exist. First, by increasing the cost of leaving, firms want to bind executives to them [25]. Second, long-term compensation should help to accumulate resources and invest in activities that are more likely to get a future competitive advantage [19]. Therefore, firms use long-term incentives such as stock options, long-term cash bonuses, phantom stocks, and restricted stocks. To distinguish those different long-term compensation instruments, we use our classification inspired by the given data of Beck et al. (2020) [26] and the classification by Claassen and Ricci (2015) [16]. This subdivision of long-term compensation allows us to determine four different long-term compensation types: pension compensation, multi-year bonus compensation, stock compensation, and stock option compensation. Together with fixed compensation and short-term compensation, we distinguish between six different compensation components (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Classification of the different compensation components. Figure 1 classifies the CFO compensation components and outlines which components are long-term or short-term, fixed or variable, and cash-based or stock-based.

In our study, the variable long-term compensation is divided into two types of compensation: cash-based compensation and stock-based compensation. Cash-based compensation does not include any stake in corporate ownership, while stock-based compensation provides an actual or potential stake in corporate ownership [16]. Following Beck et al. (2020), compensation can also be defined as stock-based compensation if its performance measures are only based on the firm’s stock [26]. Furthermore, in contrast to variable short-term compensation incentives, long-term compensation, independent of the compensation component, should focus the CFO’s attention on long-term strategies with long-term objectives and, therefore, also on CS. Also, Hart (1995) states that firms committing themselves to CS activities have a higher chance of experiencing worse short-term but better long-term performance than their competition [24].

The cash-based compensation is split into annual payments toward the retirement funds and multi-year bonus payments. The yearly payments toward the retirement funds are usually called pension payments. The firm usually provides these payments following a defined contribution plan. According to this plan, a specific contribution, amounting to a given percentage of the CFO’s fixed salary, is granted annually to the CFO’s pension account. When retiring or if the CFO is unable to continue with their duties for other reasons such as illness, the cumulated amount is paid to the CFO over a certain time frame [26]. Thus, pension compensation is primarily dependent on fixed compensation and the CFO’s contribution.

The multi-year bonus payments depend on the performance over 2 or more years. In the beginning, a certain number of weighted performance criteria oriented toward the firm’s sustainable growth is defined. Also, the corresponding amount granted to the executive in the case of achieving one of the defined targets will be specified initially. At the end of the period, the cumulated amount is paid to the executive. As we are not interested in the payment at the end of the period but the yearly payments for achieving one or more of the defined sustainable long-term performance criteria, we use the granted amount of the multi-year bonus payments collected by Beck et al. (2020) instead [26]. Using the granted amount per year, we measure the granted amount over a single year and not over 2 or more years. As the criteria for these payments are sustainability-oriented, the CFO should be encouraged to invest in long-term initiatives, like CS investments, and not act short-sightedly [16].

Stock-based compensation can be further divided into stock and stock options. Both stock-based compensations are also multi-year compensations. Almost every year, a firm grants a specified quantity of stocks or stock options to its executives for a certain time frame. The time frame differs from 3 to 5 years, depending on the firm, and the amount of the granted stocks or stock options depends on one or more specified performance objectives. The value of these stocks or stock options is contingent on the firm’s end-of-year stock price [27][28]. Stock compensation provides an actual stake in corporate ownership in the form of stocks [16]. Also, stock-based compensation usually includes a vesting period of several years where the executives can only sell the stock or stock options when they meet specific performance criteria [26]. The use of stocks containing the transfer of ownership to the CFO as a compensation measure (stock compensation) might encourage the CFO to be more risk-averse [16]. Therefore, the CFO may be less likely to invest in CS projects as these tend to be associated with substantial cash outflows (e.g., for pollution control), eventually making them economically unattractive and thus risky [29]. On the other hand, however, the CFO’s reputation may be tied to the firm if the CFO has a significant stake in corporate ownership. Consequently, the CFO may be motivated to engage in more sustainable, responsible behavior and invest more in CS activities [16].

In contrast, stock option compensation provides only a potential stake in corporate ownership in the form of granted stock options. They are not real stocks but give the executive the right to purchase the specified, granted amount of firm stocks at a specified price for a limited time [28]. As the use of stock options as a means of compensation may reduce the CFO’s risk aversion, the CFO should be more likely to invest in risky projects that would be rejected otherwise [16]. For example, Sanders and Hambrick (2007) support the claim that stock option compensation has a positive relationship with higher levels of investments that require a commitment of several years [30].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su132112299

References

- Shrivastava, P.; Hart, S. Creating sustainable corporations. Bus. Strat. Env. 1995, 4, 154–165.

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295.

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141.

- van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105.

- Berger, I.E.; Cunningham, P.H.; Drumwright, M.E. Mainstreaming corporate social responsibility: Developing markets for virtue. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 49, 132–157.

- Deckop, J.R.; Merriman, K.K.; Gupta, S. The effects of CEO pay structure on corporate social performance. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 329–342.

- Lueg, R.; Pesheva, R. Corporate sustainability in the Nordic countries—The curvilinear effects on shareholder returns. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 127962.

- Lueg, K.; Krastev, B.; Lueg, R. Bidirectional effects between organizational sustainability disclosure and risk. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 268–277.

- Hill, C.W.L.; Jones, T.M. Stakeholder-Agency theory. J. Manag. Stud. 1992, 29, 131–154.

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Reprint; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 2002; ISBN 1841120847.

- Lozano, R. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846.

- Kock, C.J.; Santaló, J.; Diestre, L. Corporate governance and the environment: What type of governance creates greener companies? J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 492–514.

- Lueg, R.; Radlach, R. Managing sustainable development with management control systems: A literature review. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 158–171.

- Coombs, J.E.; Gilley, K.M. Stakeholder management as a predictor of CEO compensation: Main effects and interactions with financial performance. Strat. Mgmt. J. 2005, 26, 827–840.

- Scott, W.R. Contributing to a Theoretical Research Program. In Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development; Reprinted; Smith, K.G., Hitt, M.A., Eds.; Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 460–484. ISBN 9780199276820.

- Claasen, D.; Ricci, C. CEO compensation structure and corporate social performance: Empirical evidence from Germany: CEO-Vergütungsstrukturen und Corporate Social Performance. Eine empirische Untersuchung deutscher Unternehmen. Die Betr. 2015, 75, 327–343.

- Berrone, P.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Environmental performance and executive compensation: An integrated agency-institutional perspective. AMJ 2009, 52, 103–126.

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. AMR 1995, 20, 65–91.

- Gray, S.R.; Cannella, A.A., Jr. The role of risk in executive compensation. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 517–540.

- Stanwick, P.A.; Stanwick, S.D. CEO compensation: Does it pay to be green? Bus. Strat. Env. 2001, 10, 176–182.

- Hossain, S.; Monroe, G.S. Chief financial officers’ short- and long-term incentive-based compensation and earnings management. Aust. Account. Rev. 2015, 25, 279–291.

- Balsam, S. An Introduction to Executive Compensation; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780080490427.

- McGuire, J.; Dow, S.; Argheyd, K. CEO incentives and corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 45, 341–359.

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. AMR 1995, 20, 986.

- Kole, S.R. The complexity of compensation contracts. J. Financ. Econ. 1997, 43, 79–104.

- Beck, D.; Friedl, G.; Schäfer, P. Executive compensation in Germany. J. Bus. Econ. 2020, 90, 787–824.

- Mahoney, L.S.; Thorn, L. An examination of the structure of executive compensation and corporate social responsibility: A Canadian investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 149–162.

- Jensen, M.C.; Murphy, K.J. Performance pay and top-management incentives. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98, 225–264.

- Rees, W.; Rodionova, T. The influence of family ownership on corporate social responsibility: An International analysis of publicly listed companies. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2015, 23, 184–202.

- Sanders, W.G.; Hambrick, D.C. Swinging for the fences: The effects of ceo stock options on company risk taking and performance. AMJ 2007, 50, 1055–1078.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!