Consumer satisfaction is considered essential to long-term business success. Organizations have a need to produce products and services that yield highly satisfied and loyal consumers. Having loyal consumers reduces the costs for firms, since the expenses for acquiring new consumers are much higher than those for keeping existing ones. Studying the factors that determine consumer satisfaction is of vital importance for a company, as consumer satisfaction has been described as the best indicator of a company’s future profits. In addition, several studies have indicated that there are positive effects of consumer satisfaction on overall brand equity and its different aspects, i.e., retailer awareness, retailer associations, the retailers’ perceived quality, and retailer loyalty.

Most studies of consumer satisfaction have been based on the overall satisfaction with a product as a whole [5,9], while only a few have related consumer satisfaction to the performance of product attributes [10]. We aimed to study which type of product attribute leads to the most satisfaction, thus providing clues for providers to improve their products. We focused on attribute evaluability [12] and analyzed the ease or difficulty in evaluating a product’s attribute [13]. This was assumed to be related to consumer satisfaction [14]. Although evaluability has usually been manipulated experimentally, we studied evaluability as a consumer’s perceptions of product attributes. We aimed to show the effects of attribute evaluability on consumer satisfaction outside of the laboratory context, in a real consumer setting. This aim matched the endeavor in research to study the scaling-up of small-scale laboratory findings to larger markets and settings, as advocated by List [15].

Another basic process in the formation of consumer satisfaction is a judgment of product performance that is relative to the reference point of the product’s performance expectations [23]. In general, the positive disconfirmation of expectations (the perceived realizations of performance exceeding expectations) will lead to consumer satisfaction, whereas negative disconfirmation (the perceived realizations of performance falling short of expectations) induces dissatisfaction. From prospect theory, it is known that negative deviations from a reference point are judged more negatively than their commensurate positive deviations are judged positively [24], thus indicating asymmetric effects of product evaluations.

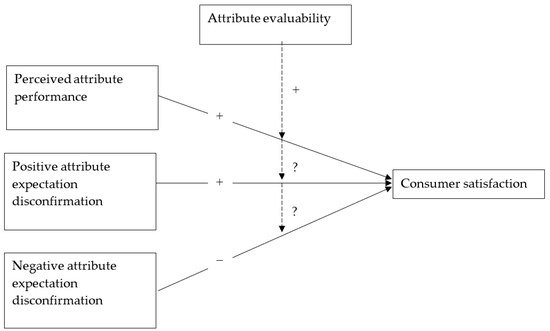

A hitherto under-researched topic is whether consumer satisfaction differs when it is due to an attribute expectation disconfirmation of easy-to-evaluate versus difficult-to-evaluate attributes. This topic is theoretically interesting, because such differences may be driven by different psychological processes. Also, it is of practical significance, because it provides a clue to providers in regard to the type of product attributes for which negative expectation disconfirmation needs to be avoided. We consider attribute evaluability as a factor that moderates the effects of attribute disconfirmation on consumer satisfaction.

- consumer satisfaction

- evaluability

- expectation disconfirmation

- loss aversion

- mobile phones

1. Satisfaction

2. Evaluability

3. Satisfaction and Loss Aversion

4. Methods

A pilot study was conducted in fall of 2018 with a Dutch convenience sample (n = 204). Since the pilot study comprised a small sample, and yielded a substantial non-response, the main study was conducted on a larger sample from Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk) in the fall of 2020.

The satisfaction scales were adapted from the American Customer Satisfaction Index [61] and comprised the following questions.

- Taken everything together, to what extent has your current phone fallen short of your expectations or exceeded your expectations? Answers ranged from 1 (this phone has definitely fallen short of my expectations) to 7 (this phone has far exceeded my expectations).

- To what extent are you satisfied with your phone? Answers ranged from 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 7 (extremely satisfied).

- Please, imagine an ideal phone. How well do you think your phone compares with that ideal phone? Answers ranged from 1 (my phone is very far from the ideal phone) to 7 (my phone is very close to the ideal phone).

The Cronbach’s alpha of the satisfaction scale was 0.782, which could not be improved by omitting one of the questions.

Evaluability has been defined as the degree of perceived ease of evaluating an attribute’s quality [5]. In order to measure how easy or difficult it was for respondents to evaluate the aspects of their phone, the following question was asked: “How was evaluating the following aspects of your phone for you? (1) very difficult–(7) very easy.” This question was asked for each of the 15 phone attributes taken both from the pilot study and from ACSI [62].

Two common approaches for measuring disconfirmation exist: (1) directly measuring the perceived gap between performance and expectation, and (2) subtracting the retrospective expectation from the perceived current performance [28]. Here, we focused on the direct measures of disconfirmation in our survey. Based on Oliver [26], we asked: “How have the following aspects of your phone performed in comparison to your expectations?” A 7-point scale ranging from 1 (much worse than you thought) to 7 (much better than you thought) was used to indicate the disconfirmation for each of the aspects of the mobile phone; the neutral midpoint was 4 (the same as you expected). Positive disconfirmation was classified as scale values above 4, and negative disconfirmation as scale values below 4. At the scale value of 4, both positive and negative disconfirmation were set equal to 0. This procedure resulted in scales of the same length.

As recommended by Oliver [63], the questions regarding satisfaction were posed at the end of the survey to avoid an effect of these questions on the questions about expectations and performance. In order to measure consumer satisfaction, Oliver [63] suggested asking about whether the object has met one’s expectations or not, and whether one is content or not with the object. We asked: “To what extent has your current phone met your expectations? (1) this phone has not met my expectations at all–(7) this phone has completely exceeded my expectations,” and “To what extent are you content with your phone? (1) I am not at all content with my phone–(7) I am really content with my phone.”

We estimated the effects of attribute performance, attribute expectation disconfirmation and attribute evaluability by an ordinary least squares regression, with satisfaction as the dependent variable, and attribute performance, resp. expectation disconfirmation, and sociodemographic variables for an individual, as independent variables. We assumed that the effects of attribute performance, resp. disconfirmation, were moderated by the evaluability of the attributes. More specifically, we assumed that the regression weights αj were a linear function of evaluability e, i.e., αj = b0 + b1ej.

5. Results

Attribute evaluability was rated at the higher end of the seven-point scale, whereas service, warranty, battery quality, and durability ranked relatively low. These attributes are important in determining the lifetime of mobile phones, and are indirectly related to sustainability issues.

Here, we focused on the moderating effect of evaluability on these effects. The results shows a significant effect of the overall perceived attribute performance, but no significant evaluability moderation effect. In regard to expectation disconfirmation, negative disconfirmation had a much stronger effect on satisfaction than positive disconfirmation , which indicated asymmetric evaluation. The moderating effect of evaluability was not significant for positive disconfirmation but was strongly negative for negative disconfirmation. The latter result indicates that the negative disconfirmation of more difficult-to-evaluate attributes had a stronger effect on satisfaction than the negative disconfirmation of more easy-to-evaluate attributes.

6. Discussion

We aimed to study the effects of the asymmetric disconfirmation of mobile phone attributes, as well as the moderating effect of attribute evaluability on consumer satisfaction. Although we found perceived attribute performance to be significantly associated with consumer satisfaction, we found no support for the perceived performance of relatively easy-to-evaluate attributes to be more strongly associated with consumer satisfaction than the perceived performance of relatively difficult-to-evaluate attributes, unlike the predictions from evaluability theory [48]. Previous experiments have used quite striking differences between easy- and difficult-to-evaluate attributes, such as a torn cover versus the number of entries in a dictionary, or an overfilled, small ice-cream versus an underfilled, large ice-cream. In actual practice, the differences between easy- and difficult-to-evaluate attributes are smaller, thus possibly explaining the lack of effect concerning consumer satisfaction in the actual consumer context. Furthermore, we included 15 attributes, whereas earlier experiments usually employed only two attributes.

We found significant effects of expectation disconfirmation on consumer satisfaction, despite the possible effects of cognitive dissonance reduction [70], or the possible distortion of facts to the advantage of the mobile phone that was in use after acquisition [71]. The latter effects would tend to mitigate the effects of disconfirmation after one becomes accustomed to using the mobile phone, but the disconfirmation effects were still significant here.

We confirmed the predictions from behavioral–economic theory, with respect to the asymmetric evaluation of gains and losses [24], and from previous research [10], in our findings of the stronger effects of negative rather than positive expectation disconfirmation on consumer satisfaction. Since evaluability theory has no predictions which regard the effects of expectation disconfirmation on consumer satisfaction, we studied these effects in an exploratory way. Our findings indicate a significant moderating effect of attribute evaluability on consumer satisfaction for negative disconfirmation, but not for positive disconfirmation. This might be due to unrealistic (i.e., too high) expectations about the difficult-to-evaluate attributes prior to the product’s acquisition, which leads to disappointment if the product’s performance is relatively low. We think of evaluability theory as a refinement of asymmetric evaluation theory regarding product attribute effects on consumer satisfaction.

As noted by others [10,72,73], the asymmetric effects of gains and losses on consumer satisfaction may have implications for product improvements by manufacturers. In general, it may be more efficient to prevent negative disconfirmation than stimulate positive disconfirmation. This may be accomplished by either providing information to manage expectations, or by improving product features frequently, which could lead to positive disconfirmation. Our study shows that there are significant effects of negative disconfirmation in the cases of difficult-to-evaluate attributes. One way to overcome these effects is to simplify the information that concerns a product’s difficult-to-evaluate attributes (for example, by showing customer reviews for such attributes), or to change the conditions of a warranty in case of deterioration or defects (for example, by offering guaranteed product performance for five years). Avoiding negative disconfirmation for difficult-to-evaluate product attributes may result in a higher overall customer satisfaction, as well as increased brand equity, without considerable investment into attributes which result in positive disconfirmation.

Since most studies on evaluability have been conducted in the laboratory, our field study is relatively unique in showing its effects on consumer satisfaction in real life [54,78]. Hence, our findings have implications for consumer product manufacturers, at least in the case of mobile phones. It appeared that attributes such as the service, battery quality, and durability of the phones were relatively difficult to evaluate for consumers, and negative disconfirmation concerning these attributes negatively affected satisfaction. Both product experiences and marketing activities may shape consumer expectations [79]. For example, bad consumer experiences may lead to low expectations at the time of repurchasing, whereas advertising and word-of-mouth might change these expectations, even after a bad product experience. With the current ability of companies and consumer agencies to analyze large datasets, it might even be possible to manage expectations based on consumer experiences. For example, consumers who report a defect in a product might be given information about the new model which does not have that defect. In our survey, durability seemed to be the most difficult-to-evaluate attribute. At least some information about the durability of a product may be made available, for example, that which concerns the statistical distribution of ownership time before product replacement. Such information could be easily gathered and estimated from consumer surveys [25]. With more accurate information about durability, consumers may be able to make better decisions concerning the lifetime of their mobile phones, which could reduce negative expectation disconfirmation, and possibly contribute to more sustainable mobile phone acquisitions.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su132212393