1. Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common degenerative neurological disorder after Alzheimer’s disease. It is caused by the prominent progressive degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra (SN) pars compacta. Molecular mechanisms underlying the degeneration of this specific neuronal population are still largely unclear, but it is known that these cells have a large axonal architecture and a so-called pacemaking activity, which puts them under an extreme bioenergetic demand for the propagation of action potentials, maintenance of membrane potential and synaptic transmission [

1,

2]. These distinctive features account for the essential role of mitochondrial dysfunction in PD pathogenesis, as demonstrated by the finding that exposure to environmental mitochondrial toxins leads to PD-like pathology [

3].

Evidence of this is that PINK1 and Parkin, both involved in mitochondrial dynamics and quality control, are the main cause of autosomal recessive (AR) early-onset PD [

4,

5,

6]. Their molecular role has been extensively studied in the last few years, revealing that the PINK1-Parkin pathway is responsible for the selective degradation of damaged mitochondria, which is necessary for the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis, especially in non-dividing cells, such as neurons.

2. PINK1 Protein Functions

PINK1 encodes a 581 acid serine/threonine-type protein kinase localized primarily in mitochondria, where it plays a pivotal role in regulating mitochondrial quality control (

mitoQC), promoting maintenance of respiring mitochondrial networks, and regulating the selective elimination of damaged mitochondria via autophagy, a process known as mitophagy [

22].

Aside from its role in mitochondrial quality control, PINK1 is also known to have a pro-survival role in preventing neuronal cell death in response to various stress conditions [

5,

23,

24].

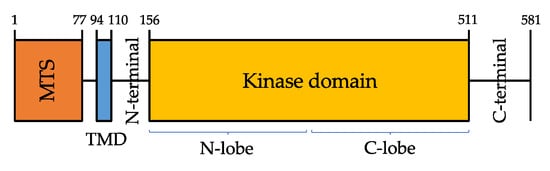

PINK1 protein is composed of a highly conserved Ser/Thr kinase domain flanked by a C-terminal, a transmembrane sequence (TMS, or TMD, transmembrane domain), and an N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) [

25] (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Domain architecture of PINK1 (581 amino acids). Mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS, orange), transmembrane domain (TMD, blue).

PINK1 kinase domain consists of amino- and carboxy-terminal lobes (N-and C-lobes), but it also has a unique feature, that is the presence of three amino acid sequences—called insertions, in addition to an unusual domain in the C-terminal region (CTR) that is not found in any other protein kinase [

26].

Kumar et al. [

27] and Schubert et al. [

28] in 2017 observed that insertion 2 contains a β-strand and an á-helix which relocate the N-lobe next to the so-called áC helix, a conserved key regulatory region of many protein kinases; this region is likely to play a role in regulating PINK1 enzymatic activity.

Moreover, the CTR and the C lobe share a hydrophobic core which explains why CTR and the kinase domain cannot be drawn apart. For what concerns insertion 3, Schubert et al. [

28] described its role in substrate binding: mutations in this insertion impair ubiquitin-like domain (UBL) and ubiquitin phosphorylation, but do not affect PINK1 autophosphorylation.

Limited information is available, instead, about the role of both CTR and insertion 1.

According to both Kumar and Schubert models, most of the disease-causing PINK1 mutations associated with PD may act altering PINK1 or selectively impairing its catalysis, phosphoregulation, or substrate binding [

26].

Elucidating the mechanisms that underlie the physiological and pathological PINK1 functioning will provide a rationale for the identification of potential PD-modifying treatments.

Dopaminergic neurons in both PD and aged individuals display dysfunctional mitochondria accumulating high levels of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) deletions [

29,

30].

Mitochondrial function impairment is strongly implicated in the etiology of PD: the first evidence for mitochondrial involvement in PD pathogenesis was the finding that chemical inhibition of mitochondrial Complex I could reproduce Parkinsonism in humans and animals [

31,

32], because inhibition of this complex induces both depletion of ATP and generation of ROS which causes oxidative stress. Moreover, the administration of the mitochondrial respiratory poison MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) in mice induces symptoms similar to those observed in sporadic PD.

All the four principal genes implicated in autosomal recessive EOPD-PRKN, PINK1, DJ-1, and VPS13C—are involved in mitochondrial homeostasis and mitophagy.

In healthy mitochondria, under normal conditions, PINK1 levels are often repressed due to its translocation to the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), where its two domains MTS and TMS are cleaved off by, respectively, MPP (mitochondria processing peptidase) [

33] and PARL (Presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein) [

34]. When deprived of MTS and TMS, the resulting 52 kDa processed PINK1 is transferred to the cytoplasm and then degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system [

35]. In response to mitochondrial stress/depolarization, the altered IMM prevents MTS and TMS from being cleaved. Full-length PINK1 is stabilized and accumulates on the mitochondrial outer membrane (OMM) where it forms a multimeric complex with outer-membrane proteins, the TOM machinery, and self-phosphorylates on Ser228, Thr257, and Ser402 to fully activate its kinase domain [

36]. Activated PINK1 phosphorylates Parkin at Serine65 (Ser65) in the N-terminal ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain, to activate Parkin enzymatic function and induce Parkin recruitment into the OMM of the damaged mitochondria [

37,

38]. Accumulation of PINK1 is crucial as a mitochondrial damage sensor, but the molecular mechanisms underlying its association with the TOM complex remain unclear [

39].

Moreover, PINK1 is also known to phosphorylate ubiquitin itself at Ser65, which then binds to the RING1 domain of Parkin with high affinity [

40,

41,

42], facilitating its conformational rearrangements and enzymatic activation.

For full activation of Parkin, phosphorylation of both the N-terminal UBL Ser65 residue of Parkin and ubiquitin is required.

Activated Parkin further attaches ubiquitin to neighboring OMM proteins so that PINK1 can recognize them as damaged proteins and phosphorylate them, which in turn amplifies Parkin activation and recruitment [

43]. PINK1/Parkin conjugated actions cause damaged mitochondria to be coated with phosphorylated Ser65-ubiquitin chains and headed towards degradation into the proteasome.

Regarding PINK1 regulation, another important role is that of phosphatase PTEN, a de-phosphorylating intracellular enzyme that negatively regulates the activity of many protein kinases. PTEN-L splicing variant, which contains an additional domain in its N-terminal, is generally located in the OMM, where its activation antagonizes PINK1-mediated phosphorylation of Parkin-UBL and ubiquitin, thus blocking mitophagy [

44].

PINK1 also coordinates several aspects of mitochondrial quality control, influencing the clearance of a wide range of substrates. Growing evidence suggests that PINK1 and Parkin are crucial for modulating mitochondrial fission and fusion, which balance is critical for the mitochondrial network. Indeed, it is known that ubiquitination of mitofusins (MFN) 1 and 2 is an early event in the PINK1-Parkin-dependent pathway. The MFN are transmembrane GTPases located in the OMM and implicated in the fusion of mitochondria. Their Parkin-dependent ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation prevent them from promoting damaged mitochondrial refusion [

45]. This process further leads to fragmentation of damaged mitochondria [

46], thus promoting mitophagy. The first hypothesis about MFN-1/-2 in mitophagy is that PINK1/Parkin-dependent ubiquitination of MFNs could induce the recruitment of ubiquitin-binding proteins which could, in turn, activate the formation of autophagosomes for damaged mitochondria; alternatively, ubiquitination of MFNs could degrade the pro-fusion proteins preventing the refusion of depolarized/damaged mitochondria with the mitochondrial network, thus contributing to segregate damaged mitochondria for degradation by mitophagy [

47].

PINK1 deficiency also affects Complex I activity, thus disrupting respiratory chain function and increasing cell susceptibility to apoptosis [

48]: Morais et al. [

49] described that Complex I phosphorylation mediated by PINK1 is essential for ubiquinone reduction to regulate mitochondrial bioenergetics. The disruption in respiratory chain function results in cellular ATP deficiency and subsequent reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential (ÄØm), which induces Parkin translocation to the OMM, where it ubiquitinates various OMM proteins and promotes the selective removal of damaged mitochondria (mitophagy). Moreover, the use of the uncoupler CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone) in mammalian cells reduces ÄØm, inducing Parkin translocation to the OMM and damaged mitochondria elimination via mitophagy.

Aside from their role in mitophagy and mitochondrial quality control, both Parkin and PINK1 have independent pro-survival activities and can prevent neuronal cell death in several stress paradigms [

50].

In 2012, Soubannier et al. [

51] firstly described an additional role of the PINK1/Parkin pathway in the regulation of a selective form of mitochondrial quality control, based on the presence of cargo-selective mitochondria-derived vesicles (MDVs). MDVs bud off mitochondria and are responsible for the degradation of damaged and oxidized mitochondrial proteins and lipid cargo into peroxisomes and other specific cargos into lysosomes, in a way that is independent of autophagy. Interestingly, at least part of MDVs trafficking is mediated by the vacuolar protein sorting 35 homolog gene (VPS35) [

52], which is known to be associated with late-onset autosomal dominant PD (PARK17) [

53,

54].

More recent studies showed the existence of an intimate connection between mitochondria and other organelles, particularly the endosomal compartment [

55,

56,

57].

Even if little is known about this complex interaction, it is likely that it plays a crucial role in influencing many mitochondrial functions, some of them regarding mitochondrial quality control processes and the release of MDVs. In fact, many proteins involved in endocytosis are also part of the process that regulates mitochondrial fission and fusion and, on the other hand, PINK1 and Parkin widely contribute to regulate mitochondrial quality control mediated by the lysosomal-dependent degradation of dysfunctional and damaged mitochondria. In this setting, PINK1-related mitochondrial dysfunction promptly results in the accumulation of altered endosomal components [

58], thus suggesting this cross-talk represents an efficient and important way for metabolites to be recycled [

59].

Nevertheless, the exact mechanisms through which mitochondria-endosome cross-talking occurs in mammalians is still unclear, as well as its implications in physiological and pathological conditions, thus limiting so far our chance to outline its possible role in PINK1-related mitochondrial impairment.

PINK1 overexpression has also been associated with reduced toxin-mediated cell death, supporting the hypothesis of a pro-survival role of this protein [

60,

61]. On the other hand, PINK1 KO mice show increased vulnerability to the complex I inhibitor MPTP, which moreover can be rescued by Parkin [

62].

Of note, cytosolic PINK1 cannot promote mitophagy [

63], suggesting that PINK1 pro-survival activity and its mitophagy-inducing role cannot be detached [

50].

In a neuronal cell culture model for synucleinopathy, the downregulation of PINK1 enhanced alpha-synuclein aggregation and apoptosis.

4. Clinical Features and Genotype-Phenotype Correlation

As the other autosomal recessive EOPD forms, PINK1-associated PD is characterized by early onset of unilateral tremor, bradykinesia and rigidity that are often indistinguishable from other PD forms, especially PRKN and idiopathic PD. However, PINK1 patients often show uncommon characteristics which can help differential diagnosis, including hyperreflexia, dystonia at onset, early L-dopa induced dyskinesias, and psychiatric and behavioral disturbances.

The mean age of onset of PD symptoms is 33 years. Lower limb dystonia may be a presenting sign, or may develop during disease progression [

18], and should raise the suspicion of PINK1-related PD. Nonmotor symptoms and sleep impairment are common in individuals with PINK1 type of young-onset PD [

64]. Also, postural instability, hyperreflexia, cognitive-behavioral disturbances and especially psychiatric symptoms -including depression (17%), anxiety (10%), and psychosis—have been reported (see

www.mdsgene.org, accessed on 10 July 2021).

Except for GBA-PINK1 is the PD-associated gene showing the highest rate of cognitive impairment, mainly concerning attention and executive functions [

65], while the prevalence of depression is comparable between PINK1 patients and idiopathic PD.

Disease progression is usually benign and L-dopa response is often marked and sustained, with a high risk of developing L-dopa induced fluctuations throughout the disease [

66].

Of note, although PINK1-related PD is associated with homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations, different heterozygous mutations have been reported in PD patients and healthy controls [

18,

19,

20], but the effect of these mutations and their potential role as a risk factor for PD is far from been understood. In the past decade, some authors reported a higher prevalence of heterozygous PINK1 rare variants in PD patients when compared to healthy controls [

18,

21,

67], thus suggesting that also heterozygous PINK1 mutations may predispose to PD. Particularly, Puschmann et al. [

68] reported a genetic association between heterozygous PINK1 p.G411S mutations and PD, providing both structural and functional evidence for a negative effect of the mutant protein thus interfering with wild-type PINK1 kinase activity.

However, a recent wide assessment of PINK1 variants in 13,708 PD patients and 362,850 controls published by Krohn et al. [

69] found no supporting evidence regarding the role of heterozygous PINK1 mutations as a risk factor for PD.

In conclusion, the spectrum of PINK1-associated phenotypes needs further investigation, especially regarding genotype-phenotype correlates; in fact, no correlation between the type of variant and age at onset, clinical presentation, or disease progression has yet been observed [

70].