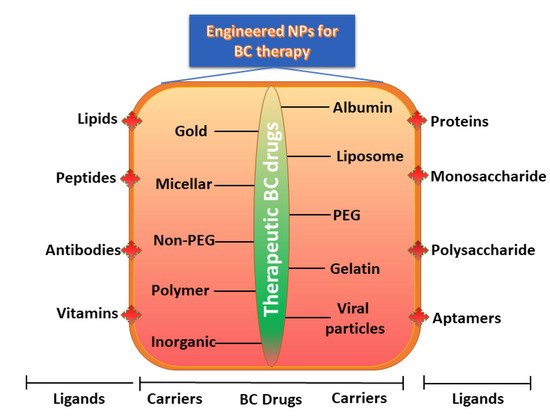

Breast cancer (BC) is the second most common cancer in women globally after lung cancer. Presently, the most important approach for BC treatment consists of surgery, followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Therapeutic drugs or natural bioactive compounds generally incorporate engineered NPs of ideal sizes and shapes to enhance their solubility, circulatory half-life, and biodistribution, while reducing their side effects and immunogenicity. Furthermore, ligands such as peptides, antibodies, and nucleic acids on the surface of NPs precisely target BC cells. Engineered NPs and their ideal methodology can be validated in the next-generation platform for preventive and therapeutic effects against BC.

- nanoparticles

- ligands

- engineering

- therapeutic effects

- breast cancer

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the outcome of aberrant and uncontrolled cell proliferation of cancerous cells in the breast tissue. BC is the second most common cancer in females and the third-leading cause of death globally [1,2]. BC therapy involves a multidisciplinary approach comprising surgery as well as radiotherapy and chemotherapy as adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies [3,4]. Chemotherapy is a technique that kills cancer cells using chemical agents. Although it is the most effective approach for cancer therapy, the cytotoxic effects of these chemotherapy agents generate various side effects [5]. Radiotherapy also decreases the risk of cancer recurrence and mortality. Nevertheless, it typically involves radiation exposure to adjacent organs, increasing the risk of cardiac and lung diseases. Such therapies may increase the risk of leukemia, especially in association with certain classes of adjuvant chemotherapy [6-8]. Conversely, these therapeutic methods are often unsuccessful in treating BC because of their adverse effects on healthy tissues and organs [9-11].

The main reason for these adverse effects and the mortality rate is the failure of therapeutic agents, which act not only on the tumor sites but also induce severe adverse effects on healthy tissues and organs, causing toxicity to the individual. BC is a highly multifaceted and heterogeneous disease and is categorized based on histopathological types. The most predominant BC cases are those of invasive ductal carcinoma, although other less-common subtypes are noteworthy due to their ferociousness and clinical manifestations [12]. The next major concern is the stage of the tumor. During cancer development, the primary tumor occurs within the breast tissue (stage 1), and then rapidly spreads to the adjacent tissues and lymph nodes (stage 2–3) or distant organs such as the lung, bone, liver, or brain (metastasis, i.e., stage 4) [13,14]. Staging of the disease is clinically important. The death rate increases as the tumor metastasizes. Moreover, BC is also categorized based on the grade and molecular subtype, viz., luminal A and B, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and triple-negative BC (TNBC) [14]. Once cancer metastasizes, the effectiveness of most standard drugs is significantly low. Finding novel, effective, and safe forms of therapy for this fatal malicious disease is thus critical. It is necessary to discover highly efficient therapeutics (the so-called “magic bullets”) which can pass through natural barriers and differentiate between benign and malignant cells in order to target malignant tissues. These agents “wisely” react to the complex tumor microenvironment for an on-demand discharge of an optimum dose range [6,15].

Tumor nanotechnology has the potential to modernize cancer diagnosis and treatment. Developments in protein engineering and material science have contributed to the development of innovative nanoscale targeting strategies, providing new optimism for BC patients. Nanoparticles (NPs), identified as pharmaceutical carriers, provide a new juncture for drug delivery to cancer cells by infiltrating tumors deeply, resulting in a high level of specificity to the targeted cancer cells [12,16-19]. Furthermore, NP treatment minimizes destructive effects on healthy tissues and organs [16,20]. Nanotechnology has been approved by the National Cancer Institute, which recognizes this technology as an outstanding paradigm-shifting approach for improving the diagnosis and treatment of BC [20].

Several therapeutic NPs, viz., Doxil®, Lipoplatin®, Onivyde®, Genexol-PM, and Abraxane®, have already been approved and are extensively employed for BC adjuvant therapy, with promising clinical outcomes [21-24]. NP-based drug delivery systems (DDSs) include several valid designs with regard to the size, shape, and nature of the biomaterials loaded with drugs, enhancing the solubility, drug stability, circulatory half-life, biodistribution, and drug release rate and reducing side effects, toxicity, and immunogenicity [25].

2. Designing of Engineered NP Carriers

Nanomedicine has the potential to evade various issues in the treatment of traditional formulations. Noteworthy strides have been made towards the application of engineered NPs for BC therapy with high sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency. The engineering of NPs primarily requires various classes of chemicals with extensive structures, sizes, and compositions [26,27]. In recent years, many techniques in nanotechnology have been developed using novel biomaterials and ligands to achieve treatments with little or no toxicity. For instance, physicochemical properties of NPs such as size, geometry or shape, composition, physical and chemical structure, charges on the surface, ligand binding, and mechanical effects can be engineered to advance their performance in vivo [28]. One fascinating example was established through the use of PEGylation, conjugation, and NP-loaded liposomes for BC diagnostics and therapeutics [29]. These techniques are feasible for reducing their deposition and toxicity in major organs to a satisfactory level by elevating their half-life in the circulation [30].

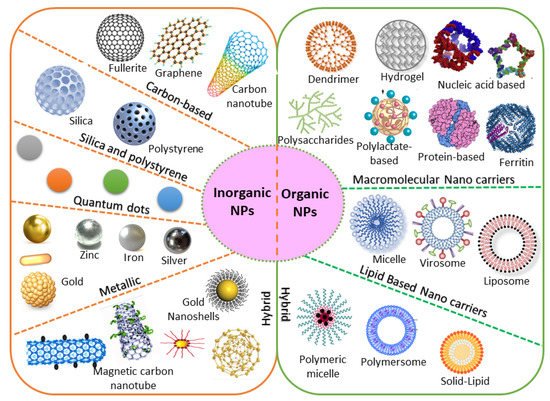

2.1. Organic/Inorganic Nanocarriers

Based on chemical requirements, NPs are classified as organic or inorganic. Organic NPs (macromolecular and lipid-based nanocarriers) are characterized by higher biocompatibility and biodegradability, with manifold activation and function of the drug on their surface. Inorganic nanoparticles (carbon, silica, quantum dots, and metallic NPs) exhibit high stability, with intrinsic and visual properties appropriate for theranostics. The most investigated types are metallic NPs (gold, silver, and iron oxide) that show distinctive properties (optical and electronic), and aid in cancer imaging [31]. Based on the stability pattern, therapeutic BC drugs are mostly conjugated on their surface. They can be degraded and exchange dynamics rapidly in vivo. Hybrid NPs occupy both organic and inorganic classes, improving the biocompatibility, biodegradability, and stability of the NPs (Figure 1). The application of inorganic NPs in therapy is inadequate due to their low biodegradability. Mesoporous inorganic NPs are typically biodegradable, and silica-based NPs enable us to preserve drugs within a porous morphology with physicochemical properties [32].

2.2. Natural/Synthetic Nanocarriers

Natural products are often attractive due to their abundance and higher biocompatibility, as well as the capacity to adapt through biochemical mechanisms [37]. Naturally occurring substances offer many benefits over their synthetic counterparts. Natural bioactive compounds encapsulated in nanocarriers can result in increased in vivo stability and water solubility, a longer circulation time of the natural product in the blood, improved biodistribution and targeting of BC cells, and controlled and sustained drug release. They are considered potent antioxidants with closer proximity and positive effects on cancer-specific pathways, with reduced side effects [38]. Natural therapeutic drugs accumulate more appropriately for longer at the tumor site through active or passive targeting of the breast tumor tissue [39]. Several in vitro and in vivo BC model studies were established and validated the antitumor functions of nano-encapsulated phytochemicals (Table 1). Furthermore, experimental studies were established using liposomes, polymers, magnetic NPs, lipid-based NPs, and protein-based NPs, confirming the potential effects of plant-based natural products for BC therapy. The association of NPs with recognized plant-based antitumor compounds has been considered a promising method to reduce tumor growth and their adverse effects [40].

Natural materials can be rapidly metabolized and removed by the body system through hydrolytic or enzymatic degradation [39]. The most common issue with natural products is that of the immune response, which can readily occur upon administration into the body. This issue is due to the protein-derived materials; however, the response is often less severe with the administration of polysaccharide (chitosan)-derived NPs [41]. This immunogenic effect can be minimized by either chemical alteration or purification to eliminate the immunogenic constituents [42].

Presently, drug delivery takes place using NP-based synthetic substances, as they allow appropriate control over the physicochemical nature of the nanoproducts. NP-based synthetic substances are stable, safe, biologically inert, and are in circulation for a longer time, improving the distribution of therapeutic BC drugs to the tumor sites. The NPs can stimulate the generation of a corona of plasma proteins near the surface. Thus, extremely charged NPs are engulfed more rapidly by the mononuclear phagocyte system than neutrally charged NPs [43,44]. Hence, using synthetic nanocarriers, the hydrophobicity and surface charges of NPs can be suitably adjusted, improving their half-life in circulation. Furthermore, their surface functions can be quickly engineered to improve their conjugation to the targeted receptors.| Drug | Nanocarriers | Natural Compound |

Size | The Outcome of the Study | BC Types | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin | Poly-glycerol-malic acid-dodecanedioic acid | Curcumin | ~110–218 nm | Significantly increased cytotoxicity, apoptotic cell death, and cellular intake compared to free drug in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 | Luminal BC and TNBC | [45] |

| Doxorubicin | Silver NPs | Andrographolide | ~450 nm | Significantly increased cytotoxicity, apoptotic cell death, and cellular intake compared to free drug in MDA-MB-453 | TNBC | [39] |

| Adriamycin | Silver NPs | Camellia sinensis | ~220 nm | Significantly increased cytotoxicity, apoptotic cell death, and cellular intake compared to free drug in MCF-7 | Luminal BC | [46] |

| Doxorubicin | Folate and chitosan | Ursolic acid | ~420 nm | Anticancer effects in an MCF-7 xenograft mouse model | Luminal BC | [41] |

| Doxorubicin | Lipid carriers (precirol® ATO 5, vitamin E, poloxamer 188, Tween 80) | Sulforaphane/Isothiocyanate | 145 nm | Anticancer effects in an MCF-7 xenograft mouse model | Luminal BC | [40] |

| Doxorubicin | Hydrophobically modified glycol chitosan with 5 beta-cholanic acid | Camptothecin | 280–330 nm | Anticancer effects in an MDA-MB-231 xenograft mousemodel | TNBC | [47] |

| Doxorubicin | Phytosome | Quercetin | ~85 nm | Anticancer effects in an MCF-7 xenograft mouse model | Luminal BC | [42] |

| Doxorubicin | PEGylated liposome |

Gambogic acid | ~107 nm | Anticancer effects in an MDA-MB-231 orthotopic xenograft mouse model |

TNBC | [48] |

2.3. Geometric Morphometry

Nanomedicine, as a discipline that involves the fields of chemistry, engineering, and material science, utilizes the unique features of NPs to design improved therapeutic BC interventions. Size, shape, density, and consistency are the key factors to be considered for not only DDSs but also for the engineering of NPs, as these factors regulate in vivo drug loading, stability, circulation, targeting capability, drug release, biodegradability, and toxicity [49]. For instance, particles that are smaller in size have a higher likelihood of accumulation during incubation and storage in vitro, and characteristically have a longer half-life in circulation in vivo [50]. Several investigations have confirmed that NPs display more benefits over micrometer-sized fragments in the range of 0.1–100 μm for DDSs [51]. The biodegradation of polymer NPs can be potentially affected by their size due to rapid degradation products.

The shape of NPs is also equally significant in the use of DDSs. Spherical NPs are generally a worthy candidate for DDSs. In addition, the morphology of anisotropy can also offer greater productivity due to their higher ratios between surface area and volume. They permit the nanocarrier to assume an encouraging shape for attachment to the cell through sharp ends and corners. Through these mechanisms, NPs can cross cell membranes and have been subjected to a wide range of investigations [52,53].

2.4. Surface Properties

The surface of the NPs represents another key factor determining the drug-loading efficacy, release profile, half-life in circulation, tumor targeting, and drug clearance. In fact, NPs generally have a hydrophilic surface to prevent protein adsorption and hence avoid uptake by the immune system [54]. This mechanism is generally achieved by coating the surface of NPs with a hydrophilic polymer (PEG), impacting toxicity, immunogenicity, and biodistribution [55].

The surface charge of NPs is often employed based on the zeta potential. It is determined according to the electrostatic potential of NPs, composition, and the medium used. Charged NPs with a zeta potential greater than 30 mV are indicated to be stable in suspensions, and these surface charges can generally avert the particles from aggregation. Furthermore, the surfaces of cells and blood vessels include several negatively charged ions, which resist negatively charged NPs. When the surface charge of NPs is higher, they can be hunted by the immune system, resulting in a higher clearance of NPs. Thus, the surface charge has a crucial role in minimizing the generic interactions between NPs and the immune system, averting NP loss in undesired settings. Surface hydrophilic PEG chains capsulated with NPs are frequently used to minimize generic interactions. PEGylation is considered to shield NPs such as liposomes, polymer NPs, and micelles from premature clearance during circulation. Various studies have suggested that PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin shows a prolonged half-life in the circulation and elevated stability, which is suggested to be linked to improved BC treatment efficacy [56-59].

Polysaccharides represent another natural surface polymer and are frequently used with NPs. They have been extensively employed in several DDSs and in tissue engineering due to their improved biocompatibility and accessibility, as well as their simple changeability. Dextran, chitosan, hyaluronic acid, fucoidan, and heparin have been employed as standard stealth-coating materials in NPs for BC therapy [60,61]. NPs coated with polysaccharides have more competent cellular uptake than other NPs due to their specific attachment with various receptors on the surface of the BC cells [62]. Hence, polysaccharides have received much attention in the field of nanomedicine.2.5. Ligands

Several methods and tools are presently accessible to shield NPs for the active targeting of BC cells. Previously, monoclonal antibodies were employed to target epitopes on the cell surface; however, the widespread screening of peptide and aptamer archives has significantly extended the number of ligands available for targeted BC therapy [63]. Various ligands are presently employed, viz., antibodies, peptides, aptamers, oligosaccharides, and small molecules, and can precisely identify and attach to an overexpressed target on the surface of the cell [61-63]. This novel targeting mode involves a type of molecular recognition that initiates the binding of the ligand receptor. This conjugation allows the NPs to fix to the surface of the tumor cell selectively. Earlier studies have also confirmed this potential binding and validated these NPs as being effective in vitro and in vivo [64-67]. For instance, when attaching to a targeting ligand, the NPs generally demonstrate advanced internalization and are subjected to receptor-mediated endocytosis [20,68]. Based on strong conjugation with ligand, the binding affinity increases and thus promotes more effective receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Monoclonal antibodies are extensively employed as targeting ligands due to their high attaching affinity and specificity for targeting BC cells, as well as their easy accessibility. Numerous investigations have been performed using monoclonal antibodies that conjugate with all families of NPs, such as superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles [69], quantum dots [70], liposomes [5], and silver nanocages [39], to contribute BC-specific targeting capacity. Using bioengineering, the monoclonal antibodies edit the redundant parts of the single-chain variable fragments, reducing the size with respect to the original antibody as well as the immunogenicity [71]. This chimeric antigen receptor-engineered T-cell is a promising tool and has extended to the treatment of other cancers, including B-cell leukemia and lymphoma [71].

Other noteworthy ligands are aptamers and peptides, which are characterized by feasible targeting methods with numerous advantages. The use of peptides shows numerous advantages, including lower molecular weight, tissue diffusion potential, loss of immunogenicity, ease of construction, and relative flexibility in chemical conjugation methods [72]. Similarly, aptamers are synthetic nucleic acid oligomers that can provide multifaceted three-dimensional structures that firmly bind to surface markers with high specificity [73]. Recently, a double aptamer–NP conjugate-based complex and adenosine triphosphate aptamer-conjugated CdTe quantum dots showed high potency for the efficient detection, monitoring, and treatment of BC [73].

Ligands such as folic acid, epidermal growth factor, and transferrin are presently more attractive for BC targeting due to their better attachment to their respective receptors with greater affinity and less immunogenicity [74-76]. Targeting ligands are nowadays receiving great attention due to their accessibility, assortment, high affinity, ease of attachment, and cost-effectiveness. Several ligands have been reported to conjugate with various receptors and NP families, as described in Table 2.

| Type of Nps | Therapeutic BC Drug |

Size of the Nps |

Ligands Used for Engineering | The Outcome of the Study | BC Types | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin-bound NPs | 2-methoxy-estradiol | ~240 nm | Bovine serum albumin | Significantly enhanced cytotoxicity and cellular uptake when compared with the free drug examined in the SK-BR-3 and MCF-7 cell lines and tumor-bearing mice | HER2 + BC | [72] |

| Chitosan | Doxorubicin | ~50 nm | Anti-HER2 peptide (5–10%) and O-succinyl chitosan graft Pluronic® F127 | Significantly enhanced cytotoxicity and cellular uptake when compared with the free drug in the MCF-7 cell line | HER2 + BC | [77] |

| Iron oxide | siRNA | 130 nm | Caffeic acid, calcium phosphate, iron oxide, PEG-polyanion block copolymer | Significantly enhanced cytotoxicity and cellular uptake when compared with free drug on HCC1954. mRNA expression was decreased by 38% when compared with naked siRNA | HER2 + BC | [78] |

| Iron oxide | Baicalein | 100 nm | PEG-coated iron oxide magnetic NPs | Significantly increased anti-apoptotic activity | TNBC | [79] |

| Liposome | Doxorubicin | ~80 nm | 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylethanolamine, Distearoylphosphatidylcholine, HER2pep-K3-palmitic acid conjugate, mPEG2000 | Significantly enhanced cytotoxicity and cellular uptake and reduced systemic toxicity when compared with the free drug in BT-474, SK-BR-3, and MCF-7 cell lines. | HER2 + BC | [80] |

| Liposome | Anti-IL6R antibody, doxorubicin |

~100 nm | 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, cholesterol | Significantly increased tumor-targeting efficacy with anti-tumor metastasis effects in BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 cells | Luminal BC | [81] |

| Liposome | Doxorubicin | 194 nm | 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoryl ethanolamine, estrone conjugated dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine- PEG2000-NH2 liposomes | Significantly increased uptake in MCF-7 BC cell lines and decreased uptake in MDA-MB-231 BC cell lines | Luminal BC | [82] |

| PolymericNPs | Curcumin | ~10 nm | Chitosan NPs with an apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) | Significantly reduced tumor volume when compared to control when tested in BALB/c mice | TNBC | [83] |

| Polymeric NPs | Trastuzumab | ~125 nm | Antigen-binding fragments cut from trastuzumab)-modified NPs (Fab’-NPs) with curcumin | Significantly increased cytotoxicity and cellular uptake when compared with the free drug in the MDA-MB-453 cell lines and a xenograft mice model. | HER2 + BC | [84] |

| Polymeric NPs | Paclitaxel | ~225 nm | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) NP coated with hyaluronic acid | Significantly increased cytotoxicity and cellular uptake when compared with the free drug in MDA-MB-231. | TNBC | [85] |

| Polymeric NPs | Paclitaxel | 131.7 nm | Hyaluronic acid-coated polyethylenimine-poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) NPs with miR-542-3p | Significantly increased cytotoxicity and cellular uptake when compared with the free drug in MDA-MB-231. | TNBC | [86] |

| Polymeric NPs | Gambogic acid | 121.5 nm | Hyaluronic acid-coated polyethylenimine-poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) NPs with RAIL plasmid (pTRAIL) and gambogic acid | Significantly increased cytotoxicity, apoptotic cell death, and cellular uptake when compared with the free drug in MDA-MB-231. | TNBC | [87] |

| Polymeric NPs | Thymoquinone | ~22 nm | Pluronic® F127 NPs, hyaluronic acid-conjugated Pluronic® P123. | Significantly reduced cell growth and migration of MDA-MB-231 cell lines and xenograft Balb/c mice | TNBC | [88] |

| Solid–lipid NPs | Di-allyl-disulfide | ~116 nm | Pluronic F-68, solid–lipid NPs engineered with palmitic acid and soya lecithin and surface-modified with glycation end product antibodies | Significantly enhanced cytotoxicity and cellular uptake, augmented activity at the tumor site, and reduced systemic toxicity when compared with the free drug in MDA-MB231 | TNBC | [89] |

2.6. Polymeric Nanocarriers

2.6.1. Conjugation with Polymeric Protein

Successful DDSs are based on the attachment of the therapeutic BC drug to proteins for targeted drug delivery. These nanocarriers are directed to the BC through conjugation with the so-called antibody-conjugated NPs. These systems can protect the chemical structure of therapeutic drugs and deliver them to the BC site using a well-controlled method. Upon stimulation, the attachment of antibodies to the drug is readily degradable, reducing toxicity [91]. Therapeutic choices may be limited for certain BC subtypes, and hence nanomedicine offers hope for patients with difficult-to-treat BC [92].

A major benefit arises from the smaller size (<10 nm) of such conjugates, which leads to a comparatively longer half-life in the circulation, and makes their extravasation into the BC region more successful when compared to NPs of greater sizes [93]. Studies have indicated that protease-cleavable conjugates are more stable than disulfides, although all of them can be engineered.

Standard chemotherapy shows low response rates and short progression-free survival among patients with pretreated metastatic TNBC. However, recent clinical studies showed that sacituzumab govitecan (an antibody–drug conjugate) is well engineered. This conjugate was heavily pre-administered to patients with metastatic TNBC. The outcomes showed improved primary endpoints with fewer complications. The secondary endpoints were progression-free and overall survival, which were found to be improved [94].2.6.2. Liposomes

Liposomes are spherical vesicles (ranging from 50 to 500 nm in size) with a lipid bilayer and are generated while the lipid connects with the aqueous solution. The most commonly employed lipids are phosphatidylcholine-enriched phospholipids, which produce liposomes. They can be potentially stabilized by strengthening the bilayer with an amphiphilic, long-chain polymer holding PEG at one end, which can simultaneously decrease opsonization and lengthen the circulation time in the blood [82]. Polymeric compounds with appropriate end groups for attachments with antibodies or ligands can also be implanted into the liposome bilayer; therefore, construction-targeted delivery is conceivable. As liposomes bilayers likely mimic those of cells, they can rapidly merge with the plasma membrane [81]. When they are internalized by cells through endocytosis or passive diffusion, the lipid bilayer undergoes rapid degradation due to the acidic environment generated by the endosomes and lysosomes [69].

As shown in the illustration in Figure 2, several engineered polymeric liposomes loaded with therapeutic drugs have been used for BC [57,95,96]. Passive tissue targeting is achieved by the extravasation of NPs due to the increased vascular permeability of the BC [97]. Active cellular targeting can also be achieved using the engineered liposomes of NPs with ligands that promote cell-specific recognition and binding. Based on cellular penetration, NPs can release their contents close to the BC cells [56]. Cyclic octapeptide LXY (Cys-Asp-Gly-Phe (3,5-DiF)-Gly-Hyp-Asn-Cys)-attached liposomes carrying the therapeutic drugs doxorubicin and rapamycin targeted over-expressing integrin-α3 in a TNBC-bearing mouse model [98]. These outcomes strongly indicate that targeted combinational therapy can provide a rational approach to improve the therapeutic outcomes of TNBC. Similarly, increased antitumor activity in a TNBC xenograft mouse model has also been revealed with doxorubicin and sorafenib-loaded liposomes [99]. Taken together, research on engineered polymeric liposomes suggests the potential efficacy of the drug-loaded polymer-link liposomes platform in BC therapy.2.6.3. Lipid–Hybrid Polymer

Polymer NPs are perhaps the most widely studied carrier systems targeting drug delivery. Various synthetic polymers have been employed and investigated based on the potential effects of their hydrophobic and biodegradable nature. Furthermore, many natural polymers (such as chitosan, poly (lactic acid), poly (glycolic acid), poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid), gelatin, poly (alkyl cyanoacrylates), and poly (ε-caprolactone)) have also been employed for drug delivery in BC treatment [100,101]. When liposomes and polymeric NPs were developed, a new class of lipid-hybrid NPs providing the characteristics of both systems was also established. These lipid-hybrid NP incorporate high drug-encapsulation materials and show precise drug release, with outstanding targeting capabilities. Non-targeted drug delivery of platinum–mitaplatin using poly-D, L-lactic-co-glycolic-acid–block-PEG NPs resulted a higher degree of tumor inhibition in the TNBC xenograft mouse model [102].

Recently, anastrozole-loaded PEGylated polymer–lipid hybrid NPs showed high entrapment efficacy (80%), size consistency, and relatively low zeta-potential values (−0.50 to 6.01), and were found to induce apoptosis in ER-positive BC cells [103]. Similarly, another study showed that nanocarriers of a polymer–lipid hybrid encapsulating psoralen optimized its hydrophilic nature and bioavailability, which improved systemic delivery [104]. Li et al. [105] developed salinomycin-loaded polymer–lipid hybrid anti-HER2 NPs and investigated the anti-tumor activity. The outcome showed that the polymer–lipid hybrid was a promising candidate targeting both HER2 + breast CSCs and BC cells.

2.6.4. Dendrimers

Dendrimers are another important type of synthetic nanocarrier (with size ranges from 10 nm to 100 nm) generated by branched monomers of divergent or convergent synthesis. They appear as liposomes, showing a cavity-enriched spherical shape with a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic periphery, and are a distinctive carrier for the delivery of siRNA [106]. Wang et al. [107] established an antisense oligo attached to poly (amidoamine) dendrimers with links to the receptors of vascular endothelial growth factor and showed a significant decrease in tumor vascularization in the TNBC xenograft mouse model. Another study reported the novel dendrimer G4PAMAM conjugated with GdDOTA and DL680, administered in TNBC xenograft mice as a model for tumor imaging and drug delivery. The outcome of MRI scan and infra-red fluorescence imaging showed the emission of NPs and a significant fluorescence signal in the tumor, demonstrating the selective delivery of a small-sized (GdDOTA)42-G4-DL680 dendrimeric agent to TNBC tumors that circumvented other adjacent primary organs [108]. Hence, the dendrimer is a potential nanocarrier and targeted diagnostic and therapeutic agent in the TNBC tumor mouse model.

3. Engineered NPs Increases the Circulation Half-Life

In principle, an NP-based delivery system should integrate high drug loading capability, a long circulation half-life, effective targeting capacity, discharge programmability, stimuli receptiveness, and diagnostic features. Negatively or neutrally charged NPs generally have a longer blood half-life than positively charged NPs. Using synthetic materials, the surface charges and hydrophobicity of NPs can be suitably tuned to elevate their blood half-life. Based on a longer circulation half-life, NPs can pass the lesion multiple times, with a greater chance of accruing on the lesion site [109]. NPs larger than 200 nm are favorably excreted by the spleen. Hence, by selecting a suitable size, surface modifications in the form of PEGylation or the use of rigid NPs will result in the longest blood half-life (2–100 folds), allowing accrual in the spleen with a high percentage and thus the improvement of overall pharmacokinetic parameters [110]. For instance, PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin exhibited a prolonged circulation half-life, which is alleged to be associated with enhanced therapeutic efficacy in BC. Studies revealed that about 50% of polystyrene NPs with the size of 250 nm and coated with poloxamine 908 accrued in the spleen almost 24 h after injection[111]. To avoid clearance by the spleen or MPS, the surface of NPs should be cautiously engineered to avoid or at least alleviate opsonization [112].

4. Conclusions

BC is the second most common cancer in females worldwide. The treatment methods of BC are surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, which are often unsuccessful to treat BC due to their various side effects. Nanomedicine has been revolutionized by opening to explore new avenues for diagnosis, prevention, and therapy for BC. Usage of therapeutic drugs or natural bioactive compounds generally engineered with NPs relatively with ideal sizes, shapes, charges and enhance their solubility, circulatory half-life, biodistribution; and immunogenicity. Nanocarriers are engineered using organic, inorganic, natural, synthetic, geometric morphometry, surface properties, ligands (peptides, antibodies, aptamers, and folic acid), and polymeric nanocarriers (protein, liposomes, lipid-hybrid, dendrimers, hydrogels), which are potentially active target specific and execute their role in abolishing the tumor cells in the breast. Therapeutic BC drugs loaded with engineered nanocarriers enter into chemoresistance cancer cells through different mechanisms viz., endocytosis, passive diffusion, and plasma membrane transporters. The application of nanoformulations improves drug-specific targeting, cell interaction, and direct uptake into BC cells, which increases the treatment efficacy. Overall nanomedicine-based drug delivery with engineered NPs can advance diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes, thereby contributing to increased overall survival and patient well-being.

References

- Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Deep frying cooking oils promote the high risk of metastases in the breast-A critical review. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 144, 111648, doi:10.1016/j.fct.2020.111648.

- Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Telomerase Inhibitors from Natural Products and Their Anticancer Potential. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 19, doi:10.3390/ijms19010013.

- Zhu, H.; You, J.; Wen, Y.; Jia, L.; Gao, F.; Ganesan, K.; Chen, J. Tumorigenic risk of Angelica sinensis on ER-positive breast cancer growth through ER-induced stemness in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2021, 280, 114415, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2021.114415.

- Ganesan, K.; Wang, Y.; Gao, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J. Targeting Engineered Nanoparticles for Breast Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1829.

- Tampaki, E.C.; Tampakis, A.; Alifieris, C.E.; Krikelis, D.; Pazaiti, A.; Kontos, M.; Trafalis, D.T. Efficacy and Safety of Neoadjuvant Treatment with Bevacizumab, Liposomal Doxorubicin, Cyclophosphamide and Paclitaxel Combination in Locally/Regionally Advanced, HER2-Negative, Grade III at Premenopausal Status Breast Cancer: A Phase II Study. Clin Drug Investig 2018, 38, 639-648, doi:10.1007/s40261-018-0655-z.

- Ganesan, K.; Sukalingam, K.; Xu, B. Impact of consumption of repeatedly heated cooking oils on the incidence of various cancers- A critical review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 488-505, doi:10.1080/10408398.2017.1379470.

- Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Molecular targets of vitexin and isovitexin in cancer therapy: a critical review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2017, 1401, 102-113, doi:10.1111/nyas.13446.

- Ganesan, K.; Jayachandran, M.; Xu, B. Diet-Derived Phytochemicals Targeting Colon Cancer Stem Cells and Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, doi:10.3390/ijms21113976.

- Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Ganesan, K.; Kewu, Z.; Shen, J.; Gang, F.; Luo, X.; Chen, J. The Antitriple Negative Breast cancer Efficacy of Spatholobus suberectus Dunn on ROS-Induced Noncanonical Inflammasome Pyroptotic Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 5187569, doi:10.1155/2021/5187569.

- Sun, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhao, Y.; He, Y.H.; Zheng, X.; Mao, W.; Jia, L.; Ganesan, K.; Chen, J. IMPACT OF TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE CONSTITUTION ON BREAST CANCER INCIDENCE: A CASE-CONTROL AND CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY. Pharmacophore 2021, 12, 46.

- Jayasuriya, R.; Dhamodharan, U.; Ali, D.; Ganesan, K.; Xu, B.; Ramkumar, K.M. Targeting Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway by bioactive natural agents: Possible therapeutic strategy to combat liver disease. Phytomedicine 2021, 92, 153755, doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153755.

- Mickymaray, S. One-step Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Saudi Arabian Desert Seasonal Plant Sisymbrium irio and Antibacterial Activity Against Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Strains. Biomolecules 2019, 9, doi:10.3390/biom9110662.

- Wu, D.; Si, M.; Xue, H.-Y.; Wong, H.-L. Nanomedicine applications in the treatment of breast cancer: current state of the art. International journal of nanomedicine 2017, 12, 5879-5892, doi:10.2147/IJN.S123437.

- Sinn, H.P.; Kreipe, H. A Brief Overview of the WHO Classification of Breast Tumors, 4th Edition, Focusing on Issues and Updates from the 3rd Edition. Breast Care (Basel) 2013, 8, 149-154, doi:10.1159/000350774.

- Peer, D.; Karp, J.M.; Hong, S.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Margalit, R.; Langer, R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nature Nanotechnology 2007, 2, 751-760, doi:10.1038/nnano.2007.387.

- Chen, H.; Feng, X.; Gao, L.; Mickymaray, S.; Paramasivam, A.; Abdulaziz Alfaiz, F.; Almasmoum, H.A.; Ghaith, M.M.; Almaimani, R.A.; Aziz Ibrahim, I.A. Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway with copper oxide nanoparticles from Houttuynia cordata plant: attenuating the proliferation of cervical cancer cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2021, 49, 240-249, doi:10.1080/21691401.2021.1890101.

- Ke, Y.; Al Aboody, M.S.; Alturaiki, W.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Alfaiz, F.A.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Mickymaray, S. Photosynthesized gold nanoparticles from Catharanthus roseus induces caspase-mediated apoptosis in cervical cancer cells (HeLa). Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2019, 47, 1938-1946, doi:10.1080/21691401.2019.1614017.

- Alsagaby, S.A.; Vijayakumar, R.; Premanathan, M.; Mickymaray, S.; Alturaiki, W.; Al-Baradie, R.S.; AlGhamdi, S.; Aziz, M.A.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Alzahrani, F.A.; et al. Transcriptomics-Based Characterization of the Toxicity of ZnO Nanoparticles Against Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Int J Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 7901-7921, doi:10.2147/ijn.S261636.

- Mickymaray, S.; Alfaiz, F.A.; Paramasivam, A. Efficacy and Mechanisms of Flavonoids against the Emerging Opportunistic Nontuberculous Mycobacteria. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9, doi:10.3390/antibiotics9080450.

- Mamnoon, B.; Loganathan, J.; Confeld, M.I.; De Fonseka, N.; Feng, L.; Froberg, J.; Choi, Y.; Tuvin, D.M.; Sathish, V.; Mallik, S. Targeted polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery to hypoxic, triple-negative breast tumors. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2021, 4, 1450-1460, doi:10.1021/acsabm.0c01336.

- O'Brien, M.E.; Wigler, N.; Inbar, M.; Rosso, R.; Grischke, E.; Santoro, A.; Catane, R.; Kieback, D.G.; Tomczak, P.; Ackland, S.P.; et al. Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCl (CAELYX/Doxil) versus conventional doxorubicin for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2004, 15, 440-449, doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh097.

- Montero, A.J.; Adams, B.; Diaz-Montero, C.M.; Glück, S. Nab-paclitaxel in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2011, 4, 329-334, doi:10.1586/ecp.11.7.

- Vishnu, P.; Roy, V. Nab-Paclitaxel: A Novel Formulation of Taxane for Treatment of Breast Cancer. Women's Health 2010, 6, 495-506, doi:10.2217/WHE.10.42.

- Nahleh, Z.A.; Barlow, W.E.; Hayes, D.F.; Schott, A.F.; Gralow, J.R.; Sikov, W.M.; Perez, E.A.; Chennuru, S.; Mirshahidi, H.R.; Corso, S.W.; et al. SWOG S0800 (NCI CDR0000636131): addition of bevacizumab to neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel with dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide improves pathologic complete response (pCR) rates in inflammatory or locally advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016, 158, 485-495, doi:10.1007/s10549-016-3889-6.

- Ghafari, M.; Haghiralsadat, F.; Khanamani Falahati-pour, S.; Zavar Reza, J. Development of a novel liposomal nanoparticle formulation of cisplatin to breast cancer therapy. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2020, 121, 3584-3592, doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.29651.

- Kumari, P.; Ghosh, B.; Biswas, S. Nanocarriers for cancer-targeted drug delivery. J Drug Target 2016, 24, 179-191, doi:10.3109/1061186x.2015.1051049.

- Navya, P.N.; Kaphle, A.; Srinivas, S.P.; Bhargava, S.K.; Rotello, V.M.; Daima, H.K. Current trends and challenges in cancer management and therapy using designer nanomaterials. Nano Converg 2019, 6, 23, doi:10.1186/s40580-019-0193-2.

- Liu, Z.; Balasubramanian, V.; Bhat, C.; Vahermo, M.; Mäkilä, E.; Kemell, M.; Fontana, F.; Janoniene, A.; Petrikaite, V.; Salonen, J.; et al. Quercetin-Based Modified Porous Silicon Nanoparticles for Enhanced Inhibition of Doxorubicin-Resistant Cancer Cells. Adv Healthc Mater 2017, 6, doi:10.1002/adhm.201601009.

- Jokerst, J.V.; Lobovkina, T.; Zare, R.N.; Gambhir, S.S. Nanoparticle PEGylation for imaging and therapy. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011, 6, 715-728, doi:10.2217/nnm.11.19.

- Allen, T.M.; Cullis, P.R. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013, 65, 36-48, doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037.

- Bayda, S.; Hadla, M.; Palazzolo, S.; Riello, P.; Corona, G.; Toffoli, G.; Rizzolio, F. Inorganic Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy: A Transition from Lab to Clinic. Curr Med Chem 2018, 25, 4269-4303, doi:10.2174/0929867325666171229141156.

- Yang, Y.; Yu, C. Advances in silica based nanoparticles for targeted cancer therapy. Nanomedicine 2016, 12, 317-332, doi:10.1016/j.nano.2015.10.018.

- Tang, W.L.; Tang, W.H.; Li, S.D. Cancer theranostic applications of lipid-based nanoparticles. Drug Discov Today 2018, 23, 1159-1166, doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2018.04.007.

- García-Pinel, B.; Porras-Alcalá, C.; Ortega-Rodríguez, A.; Sarabia, F.; Prados, J.; Melguizo, C.; López-Romero, J.M. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles: Application and Recent Advances in Cancer Treatment. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2019, 9, doi:10.3390/nano9040638.

- Date, T.; Nimbalkar, V.; Kamat, J.; Mittal, A.; Mahato, R.I.; Chitkara, D. Lipid-polymer hybrid nanocarriers for delivering cancer therapeutics. J Control Release 2018, 271, 60-73, doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.12.016.

- Guo, J.; Huang, L. Membrane-core nanoparticles for cancer nanomedicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2020, 156, 23-39, doi:10.1016/j.addr.2020.05.005.

- Ombredane, A.S.; Silva, V.R.P.; Andrade, L.R.; Pinheiro, W.O.; Simonelly, M.; Oliveira, J.V.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Gonçalves, G.F.; Felice, G.J.; Garcia, M.P.; et al. In Vivo Efficacy and Toxicity of Curcumin Nanoparticles in Breast Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11, doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.612903.

- Kashyap, D.; Tuli, H.S.; Yerer, M.B.; Sharma, A.; Sak, K.; Srivastava, S.; Pandey, A.; Garg, V.K.; Sethi, G.; Bishayee, A. Natural product-based nanoformulations for cancer therapy: Opportunities and challenges. Semin Cancer Biol 2021, 69, 5-23, doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.08.014.

- Karuppiah, A.; Rajan, R.; Ramanathan, M.; Nagarajan, A. Cytotoxicity and Synergistic Effect of Biogenically Synthesized Ternary Therapeutic Nano Conjugates Comprising Plant Active Principle, Silver and Anticancer Drug on MDA-MB-453 Breast Cancer Cell Line. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2020, 21, 195-204, doi:10.31557/apjcp.2020.21.1.195.

- Soni, K.; Rizwanullah, M.; Kohli, K. Development and optimization of sulforaphane-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers by the Box-Behnken design for improved oral efficacy against cancer: in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo assessments. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2018, 46, 15-31, doi:10.1080/21691401.2017.1408124.

- Jin, H.; Pi, J.; Yang, F.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Bai, H.; Shao, M.; Huang, L.; Zhu, H.; Yang, P.; et al. Folate-Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded with Ursolic Acid Confer Anti-Breast Cancer Activities in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 30782, doi:10.1038/srep30782.

- Minaei, A.; Sabzichi, M.; Ramezani, F.; Hamishehkar, H.; Samadi, N. Co-delivery with nano-quercetin enhances doxorubicin-mediated cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells. Mol Biol Rep 2016, 43, 99-105, doi:10.1007/s11033-016-3942-x.

- Cedervall, T.; Lynch, I.; Lindman, S.; Berggård, T.; Thulin, E.; Nilsson, H.; Dawson, K.A.; Linse, S. Understanding the nanoparticle-protein corona using methods to quantify exchange rates and affinities of proteins for nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 2050-2055, doi:10.1073/pnas.0608582104.

- Dobrovolskaia, M.A.; McNeil, S.E. Immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Nat Nanotechnol 2007, 2, 469-478, doi:10.1038/nnano.2007.223.

- Kumari, M.; Sharma, N.; Manchanda, R.; Gupta, N.; Syed, A.; Bahkali, A.H.; Nimesh, S. PGMD/curcumin nanoparticles for the treatment of breast cancer. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 3824, doi:10.1038/s41598-021-81701-x.

- Yadav, A.; Mendhulkar, V.D. Antiproliferative activity of Camellia sinensis mediated silver nanoparticles on three different human cancer cell lines. J Cancer Res Ther 2018, 14, 1316-1324, doi:10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_575_16.

- Min, K.H.; Park, K.; Kim, Y.S.; Bae, S.M.; Lee, S.; Jo, H.G.; Park, R.W.; Kim, I.S.; Jeong, S.Y.; Kim, K.; et al. Hydrophobically modified glycol chitosan nanoparticles-encapsulated camptothecin enhance the drug stability and tumor targeting in cancer therapy. J Control Release 2008, 127, 208-218, doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.01.013.

- Doddapaneni, R.; Patel, K.; Owaid, I.H.; Singh, M. Tumor neovasculature-targeted cationic PEGylated liposomes of gambogic acid for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Drug Deliv 2016, 23, 1232-1241, doi:10.3109/10717544.2015.1124472.

- Toy, R.; Hayden, E.; Shoup, C.; Baskaran, H.; Karathanasis, E. The effects of particle size, density and shape on margination of nanoparticles in microcirculation. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 115101-115101, doi:10.1088/0957-4484/22/11/115101.

- Toy, R.; Peiris, P.M.; Ghaghada, K.B.; Karathanasis, E. Shaping cancer nanomedicine: the effect of particle shape on the in vivo journey of nanoparticles. Nanomedicine (London, England) 2014, 9, 121-134, doi:10.2217/nnm.13.191.

- White, B.E.; White, M.K.; Adhvaryu, H.; Makhoul, I.; Nima, Z.A.; Biris, A.S.; Ali, N. Nanotechnology approaches to addressing HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Nanotechnology 2020, 11, 12, doi:10.1186/s12645-020-00068-2.

- Shen, Z.; Ye, H.; Yi, X.; Li, Y. Membrane Wrapping Efficiency of Elastic Nanoparticles during Endocytosis: Size and Shape Matter. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 215-228, doi:10.1021/acsnano.8b05340.

- Tang, H.; Zhang, H.; Ye, H.; Zheng, Y. Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis of Nanoparticles: Roles of Shapes, Orientations, and Rotations of Nanoparticles. J Phys Chem B 2018, 122, 171-180, doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b09619.

- Kim, S.; Seo, J.; Park, H.H.; Kim, N.; Oh, J.W.; Nam, J.M. Plasmonic Nanoparticle-Interfaced Lipid Bilayer Membranes. Acc Chem Res 2019, 52, 2793-2805, doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00327.

- Khor, S.Y.; Vu, M.N.; Pilkington, E.H.; Johnston, A.P.R.; Whittaker, M.R.; Quinn, J.F.; Truong, N.P.; Davis, T.P. Elucidating the Influences of Size, Surface Chemistry, and Dynamic Flow on Cellular Association of Nanoparticles Made by Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly. Small 2018, 14, e1801702, doi:10.1002/smll.201801702.

- Basho, R.K.; Gilcrease, M.; Murthy, R.K.; Helgason, T.; Karp, D.D.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Hess, K.R.; Herbrich, S.M.; Valero, V.; Albarracin, C.; et al. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway for the Treatment of Mesenchymal Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Evidence From a Phase 1 Trial of mTOR Inhibition in Combination With Liposomal Doxorubicin and Bevacizumab. JAMA Oncol 2017, 3, 509-515, doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5281.

- Khallaf, S.M.; Roshdy, J.; Ibrahim, A. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: 8-year experience of a single center. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 2020, 32, 20, doi:10.1186/s43046-020-00034-4.

- Jehn, C.F.; Hemmati, P.; Lehenbauer-Dehm, S.; Kümmel, S.; Flath, B.; Schmid, P. Biweekly Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin (Caelyx) in Heavily Pretreated Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Phase 2 Study. Clin Breast Cancer 2016, 16, 514-519, doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2016.06.001.

- Martin-Romano, P.; Baraibar, I.; Espinós, J.; Legaspi, J.; López-Picazo, J.M.; Aramendía, J.M.; Fernández, O.A.; Santisteban, M. Combination of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus gemcitabine in heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer patients: Long-term results from a single institution experience. Breast J 2018, 24, 473-479, doi:10.1111/tbj.12975.

- Dusinska, M.; Magdolenova, Z.; Fjellsbø, L.M. Toxicological aspects for nanomaterial in humans. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 948, 1-12, doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-140-0_1.

- Jafari, M.; Sriram, V.; Xu, Z.; Harris, G.M.; Lee, J.Y. Fucoidan-Doxorubicin Nanoparticles Targeting P-Selectin for Effective Breast Cancer Therapy. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 249, 116837, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116837.

- Sui, J.; He, M.; Yang, Y.; Ma, M.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liang, J.; Sun, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. Reversing P-Glycoprotein-Associated Multidrug Resistance of Breast Cancer by Targeted Acid-Cleavable Polysaccharide Nanoparticles with Lapatinib Sensitization. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 51198-51211, doi:10.1021/acsami.0c13986.

- Kostryukova, L.V.; Tereshkina, Y.A.; Korotkevich, E.I.; Prozorovsky, V.N.; Torkhovskaya, T.I.; Morozevich, G.E.; Toropygin, I.Y.; Konstantinov, M.A.; Tikhonova, E.G. [Targeted drug delivery system for doxorubicin based on a specific peptide and phospholipid nanoparticles]. Biomed Khim 2020, 66, 464-468, doi:10.18097/pbmc20206606464.

- Muley, H.; Fadó, R.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R.; Casals, N. Drug uptake-based chemoresistance in breast cancer treatment. Biochemical Pharmacology 2020, 177, 113959, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113959.

- Zhao, Y.Z.; Dai, D.D.; Lu, C.T.; Chen, L.J.; Lin, M.; Shen, X.T.; Li, X.K.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, X.; Jin, R.R.; et al. Epirubicin loaded with propylene glycol liposomes significantly overcomes multidrug resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Lett 2013, 330, 74-83, doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2012.11.031.

- Fu, M.; Tang, W.; Liu, J.J.; Gong, X.Q.; Kong, L.; Yao, X.M.; Jing, M.; Cai, F.Y.; Li, X.T.; Ju, R.J. Combination of targeted daunorubicin liposomes and targeted emodin liposomes for treatment of invasive breast cancer. J Drug Target 2020, 28, 245-258, doi:10.1080/1061186x.2019.1656725.

- Nie, S. Understanding and overcoming major barriers in cancer nanomedicine. Nanomedicine (London, England) 2010, 5, 523-528, doi:10.2217/nnm.10.23.

- Liao, W.S.; Ho, Y.; Lin, Y.W.; Naveen Raj, E.; Liu, K.K.; Chen, C.; Zhou, X.Z.; Lu, K.P.; Chao, J.I. Targeting EGFR of triple-negative breast cancer enhances the therapeutic efficacy of paclitaxel- and cetuximab-conjugated nanodiamond nanocomposite. Acta Biomater 2019, 86, 395-405, doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2019.01.025.

- Bano, K.; Bajwa, S.Z.; Ihsan, A.; Hussain, I.; Jameel, N.; Rehman, A.; Taj, A.; Younus, S.; Zubair Iqbal, M.; Butt, F.K.; et al. Synthesis of SPIONs-CNT Based Novel Nanocomposite for Effective Amperometric Sensing of First-Line Antituberculosis Drug Rifampicin. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2020, 20, 2130-2137, doi:10.1166/jnn.2020.17204.

- Tade, R.S.; Patil, P.O. Theranostic Prospects of Graphene Quantum Dots in Breast Cancer. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2020, 6, 5987-6008, doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01045.

- Nakajima, M.; Sakoda, Y.; Adachi, K.; Nagano, H.; Tamada, K. Improved survival of chimeric antigen receptor-engineered T (CAR-T) and tumor-specific T cells caused by anti-programmed cell death protein 1 single-chain variable fragment-producing CAR-T cells. Cancer Sci 2019, 110, 3079-3088, doi:10.1111/cas.14169.

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Liu, X.; Huo, P.; Xu, Y.; Chen, W.; Xu, H.; Tian, Q. Investigation of an antitumor drug-delivery system based on anti-HER2 antibody-conjugated BSA nanoparticles. Anticancer Drugs 2018, 29, 307-322, doi:10.1097/cad.0000000000000586.

- Mohammadinejad, A.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Es'haghi, Z.; Abnous, K.; Mohajeri, S.A. Targeted imaging of breast cancer cells using two different kinds of aptamers -functionalized nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm Sci 2019, 134, 60-68, doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2019.04.012.

- Narmani, A.; Rezvani, M.; Farhood, B.; Darkhor, P.; Mohammadnejad, J.; Amini, B.; Refahi, S.; Abdi Goushbolagh, N. Folic acid functionalized nanoparticles as pharmaceutical carriers in drug delivery systems. Drug Dev Res 2019, 80, 404-424, doi:10.1002/ddr.21545.

- Du, C.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Min, H.; Han, X.; Lang, J.; Qin, H.; Shi, Q.; et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Targeting Peptide Nanoparticles Simultaneously Deliver Gemcitabine and Olaparib To Treat Pancreatic Cancer with Breast Cancer 2 ( BRCA2) Mutation. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 10785-10796, doi:10.1021/acsnano.8b01573.

- Bhagwat, G.S.; Athawale, R.B.; Gude, R.P.; Md, S.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Fahmy, U.A.; Kesharwani, P. Formulation and Development of Transferrin Targeted Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Breast Cancer Therapy. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 614290, doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.614290.

- Okines, A.F.C.; Ulrich, L. Investigational antibody-drug conjugates in clinical trials for the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2021, 30, 789-795, doi:10.1080/13543784.2021.1940950.

- Bardia, A.; Mayer, I.A.; Diamond, J.R.; Moroose, R.L.; Isakoff, S.J.; Starodub, A.N.; Shah, N.C.; O'Shaughnessy, J.; Kalinsky, K.; Guarino, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Trop-2 Antibody Drug Conjugate Sacituzumab Govitecan (IMMU-132) in Heavily Pretreated Patients With Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017, 35, 2141-2148, doi:10.1200/jco.2016.70.8297.

- Bardia, A.; Mayer, I.A.; Vahdat, L.T.; Tolaney, S.M.; Isakoff, S.J.; Diamond, J.R.; O'Shaughnessy, J.; Moroose, R.L.; Santin, A.D.; Abramson, V.G.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy in Refractory Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 741-751, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1814213.

- Kim, B.; Shin, J.; Wu, J.; Omstead, D.T.; Kiziltepe, T.; Littlepage, L.E.; Bilgicer, B. Engineering peptide-targeted liposomal nanoparticles optimized for improved selectivity for HER2-positive breast cancer cells to achieve enhanced in vivo efficacy. J Control Release 2020, 322, 530-541, doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.04.010.

- Naruphontjirakul, P.; Viravaidya-Pasuwat, K. Development of anti-HER2-targeted doxorubicin-core-shell chitosan nanoparticles for the treatment of human breast cancer. Int J Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 4105-4121, doi:10.2147/ijn.S198552.

- Cristofolini, T.; Dalmina, M.; Sierra, J.A.; Silva, A.H.; Pasa, A.A.; Pittella, F.; Creczynski-Pasa, T.B. Multifunctional hybrid nanoparticles as magnetic delivery systems for siRNA targeting the HER2 gene in breast cancer cells. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2020, 109, 110555, doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.110555.

- Kavithaa, K.; Paulpandi, M.; Padma, P.R.; Sumathi, S. Induction of intrinsic apoptotic pathway and cell cycle arrest via baicalein loaded iron oxide nanoparticles as a competent nano-mediated system for triple negative breast cancer therapy. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 64531-64543, doi:10.1039/C6RA11658B.

- Guo, C.; Chen, Y.; Gao, W.; Chang, A.; Ye, Y.; Shen, W.; Luo, Y.; Yang, S.; Sun, P.; Xiang, R.; et al. Liposomal Nanoparticles Carrying anti-IL6R Antibody to the Tumour Microenvironment Inhibit Metastasis in Two Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer Mouse Models. Theranostics 2017, 7, 775-788, doi:10.7150/thno.17237.

- Salkho, N.M.; Paul, V.; Kawak, P.; Vitor, R.F.; Martins, A.M.; Al Sayah, M.; Husseini, G.A. Ultrasonically controlled estrone-modified liposomes for estrogen-positive breast cancer therapy. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2018, 46, 462-472, doi:10.1080/21691401.2018.1459634.

- Kamalabadi-Farahani, M.; Vasei, M.; Ahmadbeigi, N.; Ebrahimi-Barough, S.; Soleimani, M.; Roozafzoon, R. Anti-tumour effects of TRAIL-expressing human placental derived mesenchymal stem cells with curcumin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles in a mice model of triple negative breast cancer. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2018, 46, S1011-s1021, doi:10.1080/21691401.2018.1527345.

- Duan, D.; Wang, A.; Ni, L.; Zhang, L.; Yan, X.; Jiang, Y.; Mu, H.; Wu, Z.; Sun, K.; Li, Y. Trastuzumab- and Fab' fragment-modified curcumin PEG-PLGA nanoparticles: preparation and evaluation in vitro and in vivo. Int J Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 1831-1840, doi:10.2147/ijn.S153795.

- Cerqueira, B.B.S.; Lasham, A.; Shelling, A.N.; Al-Kassas, R. Development of biodegradable PLGA nanoparticles surface engineered with hyaluronic acid for targeted delivery of paclitaxel to triple negative breast cancer cells. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2017, 76, 593-600, doi:10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.121.

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M. Hyaluronic acid-coated PEI-PLGA nanoparticles mediated co-delivery of doxorubicin and miR-542-3p for triple negative breast cancer therapy. Nanomedicine 2016, 12, 411-420, doi:10.1016/j.nano.2015.09.014.

- Maeda, H.; Nakamura, H.; Fang, J. The EPR effect for macromolecular drug delivery to solid tumors: Improvement of tumor uptake, lowering of systemic toxicity, and distinct tumor imaging in vivo. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013, 65, 71-79, doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.002.

- Juan, A.; Cimas, F.J.; Bravo, I.; Pandiella, A.; Ocaña, A.; Alonso-Moreno, C. Antibody Conjugation of Nanoparticles as Therapeutics for Breast Cancer Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, doi:10.3390/ijms21176018.

- Wang, S.; Shao, M.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, A.; Cao, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Co-delivery of gambogic acid and TRAIL plasmid by hyaluronic acid grafted PEI-PLGA nanoparticles for the treatment of triple negative breast cancer. Drug Deliv 2017, 24, 1791-1800, doi:10.1080/10717544.2017.1406558.

- Dillman, R.O. Cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2011, 26, 1-64, doi:10.1089/cbr.2010.0902.

- Bhattacharya, S.; Ghosh, A.; Maiti, S.; Ahir, M.; Debnath, G.H.; Gupta, P.; Bhattacharjee, M.; Ghosh, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Mukherjee, P.; et al. Delivery of thymoquinone through hyaluronic acid-decorated mixed Pluronic® nanoparticles to attenuate angiogenesis and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer. J Control Release 2020, 322, 357-374, doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.03.033.

- Ardavanis, A.; Mavroudis, D.; Kalbakis, K.; Malamos, N.; Syrigos, K.; Vamvakas, L.; Kotsakis, A.; Kentepozidis, N.; Kouroussis, C.; Agelaki, S.; et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in combination with vinorelbine as salvage treatment in pretreated patients with advanced breast cancer: a multicentre phase II study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2006, 58, 742-748, doi:10.1007/s00280-006-0236-3.

- Yang, F.O.; Hsu, N.C.; Moi, S.H.; Lu, Y.C.; Hsieh, C.M.; Chang, K.J.; Chen, D.R.; Tu, C.W.; Wang, H.C.; Hou, M.F. Efficacy and toxicity of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-based chemotherapy in early-stage breast cancer: a multicenter retrospective case-control study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2018, 14, 198-203, doi:10.1111/ajco.12771.

- Chan, S.; Davidson, N.; Juozaityte, E.; Erdkamp, F.; Pluzanska, A.; Azarnia, N.; Lee, L.W. Phase III trial of liposomal doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide compared with epirubicin and cyclophosphamide as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2004, 15, 1527-1534, doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh393.

- Dai, W.; Yang, F.; Ma, L.; Fan, Y.; He, B.; He, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q. Combined mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and doxorubicin-loaded cyclic octapeptide modified liposomes for targeting integrin α3 in triple-negative breast cancer. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5347-5358, doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.036.

- Lee, S.M.; Ahn, R.W.; Chen, F.; Fought, A.J.; O'Halloran, T.V.; Cryns, V.L.; Nguyen, S.T. Biological evaluation of pH-responsive polymer-caged nanobins for breast cancer therapy. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4971-4978, doi:10.1021/nn100560p.

- Naskar, S.; Koutsu, K.; Sharma, S. Chitosan-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems: a review on two decades of research. J Drug Target 2019, 27, 379-393, doi:10.1080/1061186x.2018.1512112.

- Elzoghby, A.O. Gelatin-based nanoparticles as drug and gene delivery systems: reviewing three decades of research. J Control Release 2013, 172, 1075-1091, doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.09.019.

- Johnstone, T.C.; Kulak, N.; Pridgen, E.M.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Langer, R.; Lippard, S.J. Nanoparticle encapsulation of mitaplatin and the effect thereof on in vivo properties. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 5675-5683, doi:10.1021/nn401905g.

- Massadeh, S.; Omer, M.E.; Alterawi, A.; Ali, R.; Alanazi, F.H.; Almutairi, F.; Almotairi, W.; Alobaidi, F.F.; Alhelal, K.; Almutairi, M.S.; et al. Optimized Polyethylene Glycolylated Polymer-Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticles as a Potential Breast Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics12070666.

- Du, M.; Ouyang, Y.; Meng, F.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Q.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, H.; Pang, M.; Cai, T.; Cai, Y. Polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticles: A novel drug delivery system for enhancing the activity of Psoralen against breast cancer. Int J Pharm 2019, 561, 274-282, doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.03.006.

- Li, J.; Xu, W.; Yuan, X.; Chen, H.; Song, H.; Wang, B.; Han, J. Polymer-lipid hybrid anti-HER2 nanoparticles for targeted salinomycin delivery to HER2-positive breast cancer stem cells and cancer cells. Int J Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 6909-6921, doi:10.2147/ijn.S144184.

- Tambe, V.; Thakkar, S.; Raval, N.; Sharma, D.; Kalia, K.; Tekade, R.K. Surface Engineered Dendrimers in siRNA Delivery and Gene Silencing. Curr Pharm Des 2017, 23, 2952-2975, doi:10.2174/1381612823666170314104619.

- Wang, P.; Zhao, X.H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Meng, M.; Li, X.; Ning, Q. Generation 4 polyamidoamine dendrimers is a novel candidate of nano-carrier for gene delivery agents in breast cancer treatment. Cancer Lett 2010, 298, 34-49, doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2010.06.001.

- Zhang, L.; Varma, N.R.; Gang, Z.Z.; Ewing, J.R.; Arbab, A.S.; Ali, M.M. Targeting Triple Negative Breast Cancer with a Small-sized Paramagnetic Nanoparticle. J Nanomed Nanotechnol 2016, 7, doi:10.4172/2157-7439.1000404.

- Jin-Wook, Y.; Elizabeth, C.; Samir, M. Factors that Control the Circulation Time of Nanoparticles in Blood: Challenges, Solutions and Future Prospects. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2010, 16, 2298-2307, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/138161210791920496.

- Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.S.; Pang, B.; Hyun, D.C.; Yang, M.; Xia, Y. Engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2014, 53, 12320-12364, doi:10.1002/anie.201403036.

- Zaman, R.; Islam, R.A.; Ibnat, N.; Othman, I.; Zaini, A.; Lee, C.Y.; Chowdhury, E.H. Current strategies in extending half-lives of therapeutic proteins. J Control Release 2019, 301, 176-189, doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.02.016.

- Baharifar, H.; Khoobi, M.; Arbabi Bidgoli, S.; Amani, A. Preparation of PEG-grafted chitosan/streptokinase nanoparticles to improve biological half-life and reduce immunogenicity of the enzyme. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 143, 181-189, doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.157.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pharmaceutics13111829