Democratic Dialogue is a participatory development process that involves those concerned to find ways to meet shared challenges in agreement. In this entry, Democratic Dialogue is described as a classic Nordic workplace development method that is often carried out in Participatory Action Research (PAR) setting. The method is applicable also in other than workplace related organizational and societal issues.

- Democratic Dialogue

- workplace democracy

- workplace development

1. Introduction

In the Scandinavian context the concept of Democratic Dialogue is linked to a Swedish workplace development programme LOM (Ledning, organisation och medbestämmande; Leadership, organization and co-determination) [1]. The underlying theoretical ideas are linked to the changes of how workplace (industrial) democracy is understood and to the role of communication in work organizations. When workplace democracy is defined in terms of how organizational patterns are created, instead of terms of those patterns as such, workplace democracy is seen equivalent to generative capacity. This starting point is derived from theories of communication that take communication as the constitutive force in social life: the quality of all human thought and action ultimately depends on the patterns of communication between actors. While meanings are created and organizations are built in communication processes, power relations are also maintained and reproduced by communication that either supports or rejects different organizational experiences. From this point of view, it seems reasonable and practical to change the patterns of communication and to bring forward diverse experiences about work in the pursuit of desirable change. When this is combined with the basic principle of democracy – seeing all participants as having equal rights – the best, or most rational solutions are likely to appear in open discussions among those concerned. [2] Building on these premises, the concept of Democratic Dialogue was chosen as a key concept in the theory of communication used in LOM-programme [1].

2. Applications and the role of the criteria of Democratic Dialogue

Since in Democratic Dialogue it is all about making changes in organizations via communication and in a democratic way, there is a need for communication forums that acknowledge work experience as a resource for participation. Dialogue conferences, special meetings of those concerned, have been used for the explicit purpose of training the participants in democratic procedures while discussing what visions they would like to pursue and how to do it [3]. Although the essence of Democratic Dialogue in practice can be seen as an emergent matter, evolving during development efforts and along learning processes of the participants, the concept has been operationalized [1], giving rise to practical applications in human encounters, for example in multiactor sessions, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. An illustration of getting familiar with the concept of Democratic Dialogue in practice.

The operationalization of the concept of Democratic Dialogue can be taken as a set of criteria, principles or orientational directives [1] [3]. Below, one of the English-language versions of the criteria of democratic dialogue is presented [3] (pp. 18-19, the numbering of the criteria is by the authors):

1. Dialogue is based on the principle of give and take, not one-way communication.

2. All concerned by the issue under discussion should have the opportunity to participate.

3. Participants are under an obligation to help the other participants be active in the dialogue.

4. All participants have the same status in the dialogue arenas.

5. Work experience is the point of departure for participation.

6. Some of the experience the participant has when entering the dialogue must be seen as relevant.

7. It must be possible for all participants to gain an understanding of the topics under discussion.

8. An argument can be rejected only after an investigation (and not, for instance, on the grounds

that it emanates from a source with limited legitimacy).

9. All arguments that are to enter the dialogue must be presented by the actors present.

10. All participants are obliged to accept that other participants may have arguments better than

their own.

11. Among the issues that can be made subject to discussion are the ordinary work roles of the

participants—no one is exempt from such discussion.

12. The dialogue should be able to integrate a growing degree of disagreement.

13. The dialogue should continuously generate decisions that provide a platform for joint action.”

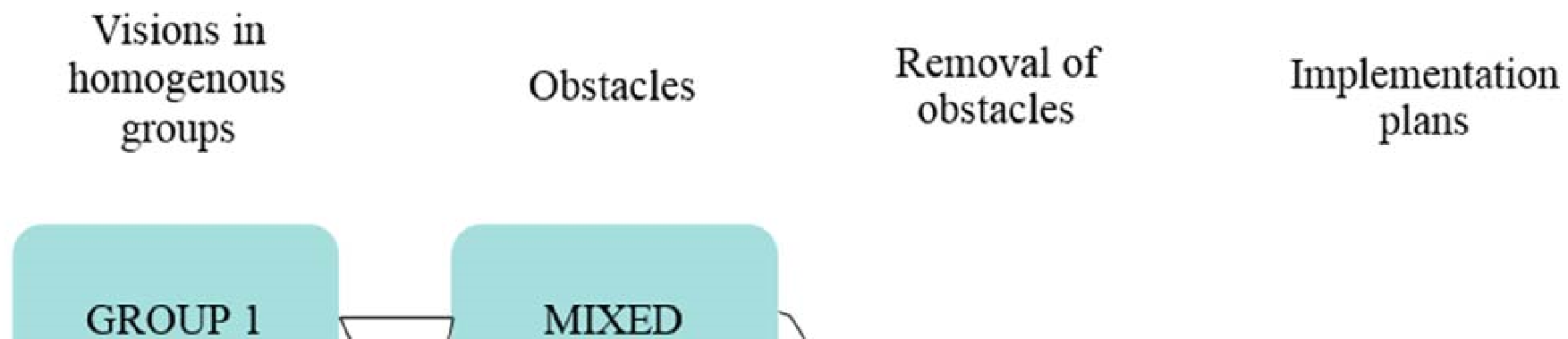

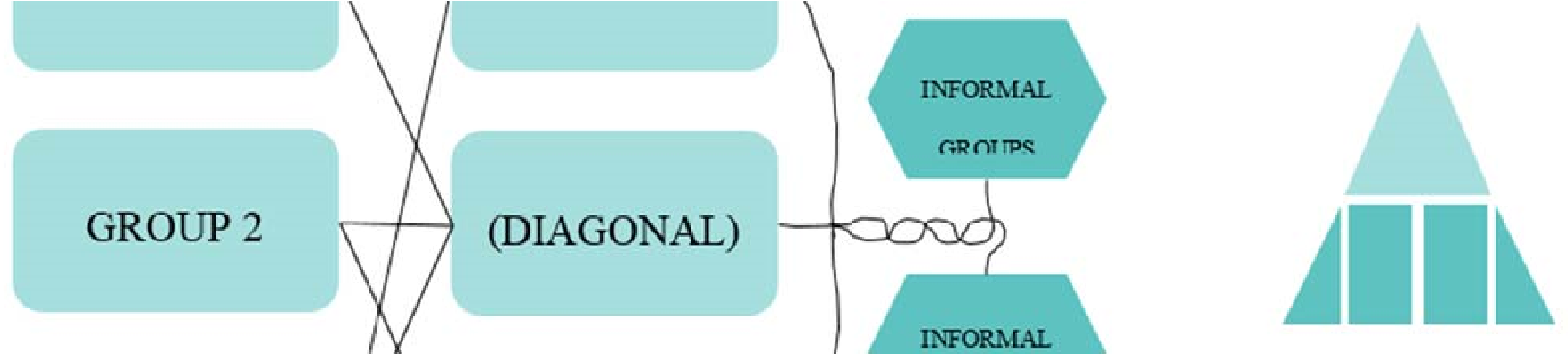

In Finnish workplace development applications Democratic Dialogue was often adopted as rules to be followed on dialogue forums and once learned, transferred to other planning groups as a regular way of working. Dialogue conferences, called as work conferences, were modeled as an interplay between small groups and plenaries that were conducted according to a design deduced from the criteria of Democratic Dialogue. The role of the facilitators, for example action researchers, was limited to introducing the rules and the overall conduct of the conferences. All the topics and the contents of the dialogues were brought forward by the participants, based on the criteria 5 and 9. The Swedish LOM Progam was applied in a network form encouraging participating organizations to learn from each other [1]. The network form has been utilized also in Finnish applications [4], but Democratic Dialogue has been found useful also within single organizations. Both in the Finnish and LOM models the problems and flaws are put aside as the starting point is the desirable future within a time span of five years, see Figure 2.

Figure 2. The progression of the dialogue (work) conference

When dialogue/work conferences are organized as parts of development projects with an agreed time span, there will be the final conference. After that it is up to the participants how to go on. The aim is to adopt Democratic Dialogue as a mainstream way of communication in all staff-management and service provider-client -meetings, not only in special encounters.

3. Mechanisms and outcomes of Democratic Dialogue

The initial starting point for communicative theory in the use of workplace development – applying workplace democracy means applying generative capacity [2],[1] – may be evaluated by identifying the mechanisms and outcomes of Democratic Dialogue. Dalkin et al. (2015) [5] advice to ask whether DD produces new resources, reasoning and choices for the participants and if yes, through what mechanisms. The mechanisms must be linked to the changes in the organizational patterns of communication culminated in the design of work conferences and of the criteria of Democratic Dialogue. In other words, what is changed when Democratic Dialogue is adopted as a method of responding to organizational challenges? [4]

Offering Dialogue Forums to Work Organizations by dialogue forums as a whole

The democratic dialogue approach involves the establishment of a new type of communication forum that hierarchical organizations do not usually have. It represents an innovative resource that is able to respond to the needs to plan the work together, establish ground rules, and redistribute responsibility, aiming both to secure the smooth running of the daily activities and to respond to current change demands.

Offering Learning Space and Learning from Others by following especially Criteria 1, 7, and 10

Understanding the concept of dialogue is vital. In Criterion 1, dialogue is explained as the process of giving and taking instead of one-way communication, and in Criterion 7, the aim to learn is fully explicit. Participants frequently seem to find at least some common elements in the other participants’ experiences, but they may also uncover totally new perspectives, and these contribute to the process of mutual learning. Criterion 10 counsels the participants to accept the potentially better arguments of others, and thus widen their scope of learning.

Increasing Agency by Involving Oneself in the Dialogues by following criteria 2–6 and 8–9

The inherent values emphasizing the work experience of every participant in the main body of the criteria are significant to the grass-roots-level employees. When they see the dialogue forums enabling (or sometimes obliging) them to express their perspectives and to take a stand to do this, they may find their resources to be active agents in their work organization.

Enabling the Expression of Individual and Group Interests by following Criterion 2 and offering dialogues in homogenous groups

In addition to the potential to increase agency, Criterion 2 encourages the participants to express and combine their individual interests into a future vision in homogenous groups (Figure 2). The dialogues in homogenous groups are highly significant for the whole process, since the visions created by them form the basis of the following dialogues. As professional or occupational boundaries and identities are often seen as constraints to genuine client orientations in the rank order of occupations, the members of these groups use the resources offered by democratic dialogue to express their views.

Making Use of the Dialogues Enhances Trust and Commitment by following especially criteria 11–13

In a work conference, after hearing about the obstacles of visions and available means to carry them out, and alongside learning, the dialogue should be able to integrate the various perspectives to create a joint action plan. The crucial phase —turning words into action – comes after the conferences. If planned action does not take place, the participants will usually be frustrated and lose their potential commitment to further dialogues.

Summary of the outcomes produced by mechanisms

Participants have found new resources and new ways to reason, and they have made new choices to carry out the plans created in the dialogue forums. In addition, they have been in positions to ensure the practical actions. No practical outcomes would be possible without the participants, since the action researchers are not in a position to accomplish such changes.

4. Complementary comments

In established organizations, forms of participative and high-involvement management often include elements of Democratic Dialogue, when the type of management practiced encourages to adopt dialogue as a mainstream way of communication in all staff-management and service provider-client -meetings, not only in special encounters. Also, many development co-operation projects and projects emerging from grass-root level communities have found it meaningful to hear to all concerned in the spirit of Democratic Dialogue [6].

This entry is based on https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/8/3/101

Related entry "Communicative Spaces" https://encyclopedia.pub/16154

References

- Gustavsen, Björn. The LOM Progman: A Network-Based Strategy for Organization Development in Sweden. In Research in Organizational Change and Development. Volume 5.; Woodman, Richard W. and William A. Pasmore, Eds.; JAI Press Inc.: Greenwich and London, 1991; pp. 285-315.

- Gustavsen, Björn and Engelstad, Per H.; The Design of Conferences and the Evolving Role of Democratic Dialogue in Changing Working Life. Human Relations 1986, 39 (2), 101-116, 10.1177/001872678603900201.

- Gustavsen, Björn. Theory and Practice: The Mediating Discourse. In Handbook of Action research: Participative Inquiry and Practice.; Reason, Peter and Bradbury, Hilary, Eds.; Sage: London, Thousands Oaks and New New Delhi, 2001; pp. 17-26.

- Kalliola, Satu, Heiskanen, Tuula and Kivimäki, Riikka; What works in democratic dialogue?. Social Sciences 2019, 8(3), 101, 10.3390/socsci8030101.

- Dalkin, Sonia Michele, Greenhalgh, Joanne, Jones, Diana, Cunningham, Bill, and Lhussier, Monique; What’s in a Mechanism? Development of a Key Concept in Realist Evaluation. Implementation Science 2015, 10 (49), 1-7, 10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x.

- Bruit, Bettye and Thomas, Philip . Democratic Dialogue – A Handbook for Practitioners; Canadian International Development Agency CIDA, General Secretariat of the Organization of American States OAS, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance IDEA and United Nations Development Programme UNDP: Washington D.C. USA, Stockholm, Sweden and New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1-262.